Transatlantic Relations After Trump: Mutual Perceptions and Historical Perspectives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

By Philip Roth

The Best of the 60s Articles March 1961 Writing American Fiction Philip Roth December 1961 Eichmann’s Victims and the Unheard Testimony Elie Weisel September 1961 Is New York City Ungovernable? Nathan Glazer May 1962 Yiddish: Past, Present, and Perfect By Lucy S. Dawidowicz August 1962 Edmund Wilson’s Civil War By Robert Penn Warren January 1963 Jewish & Other Nationalisms By H.R. Trevor-Roper February 1963 My Negro Problem—and Ours By Norman Podhoretz August 1964 The Civil Rights Act of 1964 By Alexander M. Bickel October 1964 On Becoming a Writer By Ralph Ellison November 1964 ‘I’m Sorry, Dear’ By Leslie H. Farber August 1965 American Catholicism after the Council By Michael Novak March 1966 Modes and Mutations: Quick Comments on the Modern American Novel By Norman Mailer May 1966 Young in the Thirties By Lionel Trilling November 1966 Koufax the Incomparable By Mordecai Richler June 1967 Jerusalem and Athens: Some Introductory Reflections By Leo Strauss November 1967 The American Left & Israel By Martin Peretz August 1968 Jewish Faith and the Holocaust: A Fragment By Emil L. Fackenheim October 1968 The New York Intellectuals: A Chronicle & a Critique By Irving Howe March 1961 Writing American Fiction By Philip Roth EVERAL winters back, while I was living in Chicago, the city was shocked and mystified by the death of two teenage girls. So far as I know the popu- lace is mystified still; as for the shock, Chicago is Chicago, and one week’s dismemberment fades into the next’s. The victims this particular year were sisters. They went off one December night to see an Elvis Presley movie, for the sixth or seventh time we are told, and never came home. -

Chapter One: Postwar Resentment and the Invention of Middle America 10

MIAMI UNIVERSITY The Graduate School Certificate for Approving the Dissertation We hereby approve the Dissertation of Jeffrey Christopher Bickerstaff Doctor of Philosophy ________________________________________ Timothy Melley, Director ________________________________________ C. Barry Chabot, Reader ________________________________________ Whitney Womack Smith, Reader ________________________________________ Marguerite S. Shaffer, Graduate School Representative ABSTRACT TALES FROM THE SILENT MAJORITY: CONSERVATIVE POPULISM AND THE INVENTION OF MIDDLE AMERICA by Jeffrey Christopher Bickerstaff In this dissertation I show how the conservative movement lured the white working class out of the Democratic New Deal Coalition and into the Republican Majority. I argue that this political transformation was accomplished in part by what I call the "invention" of Middle America. Using such cultural representations as mainstream print media, literature, and film, conservatives successfully exploited what came to be known as the Social Issue and constructed "Liberalism" as effeminate, impractical, and elitist. Chapter One charts the rise of conservative populism and Middle America against the backdrop of 1960s social upheaval. I stress the importance of backlash and resentment to Richard Nixon's ascendancy to the Presidency, describe strategies employed by the conservative movement to win majority status for the GOP, and explore the conflict between this goal and the will to ideological purity. In Chapter Two I read Rabbit Redux as John Updike's attempt to model the racial education of a conservative Middle American, Harry "Rabbit" Angstrom, in "teach-in" scenes that reflect the conflict between the social conservative and Eastern Liberal within the author's psyche. I conclude that this conflict undermines the project and, despite laudable intentions, Updike perpetuates caricatures of the Left and hastens Middle America's rejection of Liberalism. -

Constructing Neo-Conservatism

Stephen Eric Bronner Constructing Neo-Conservatism by Stephen Eric Bronner eo-conservatism has become both a code word for reactionary thinking Nin our time and a badge of unity for those in the Bush administration advocating a new imperialist foreign policy, an assault on the welfare state, and a return to “family values.” Its members are directly culpable for the disintegration of American prestige abroad, the erosion of a huge budget surplus, and the debasement of democracy at home. Enough inquiries have highlighted the support given to neo-conservative causes by various businesses and wealthy foundations like Heritage and the American Enterprise Institute. In general, however, the mainstream media has taken the intellectual pretensions of this mafia far too seriously and treated its members far too courteously. Its truly bizarre character deserves particular consideration. Thus, the need for what might be termed a montage of its principal intellectuals and activists. Montage NEO-CONSERVATIVES WIELD EXTRAORDINARY INFLUENCE in all the branches and bureaucracies of the government. Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld and Deputy Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz really require no introduction. These architects of the Iraqi war purposely misled the American public about the existence of weapons of mass destruction, a horrible pattern of torturing prisoners of war, the connection between Saddam Hussein and al Qaeda, the celebrations that would greet the invading troops, and the ease of setting up a democracy in Iraq. But they were not alone. Whispering words of encouragement was the notorious Richard Perle: a former director of the Defense Policy Board, until his resignation amid accusations of conflict of interest, his nickname—“the Prince of Darkness”—reflects his advanced views on nuclear weapons. -

Neoconservatism Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative Hberkc Ch5 Mp 104 Rev1 Page 104 Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative Hberkc Ch5 Mp 105 Rev1 Page 105

Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative hberkc ch5 Mp_103 rev1 page 103 part iii Neoconservatism Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative hberkc ch5 Mp_104 rev1 page 104 Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative hberkc ch5 Mp_105 rev1 page 105 chapter five The Neoconservative Journey Jacob Heilbrunn The Neoconservative Conspiracy The longer the United States struggles to impose order in postwar Iraq, the harsher indictments of the George W. Bush administration’s foreign policy are becoming. “Acquiring additional burdens by engag- ing in new wars of liberation is the last thing the United States needs,” declared one Bush critic in Foreign Affairs. “The principal problem is the mistaken belief that democracy is a talisman for all the world’s ills, and that the United States has a responsibility to promote dem- ocratic government wherever in the world it is lacking.”1 Does this sound like a Democratic pundit bashing Bush for par- tisan gain? Quite the contrary. The swipe came from Dimitri Simes, president of the Nixon Center and copublisher of National Interest. Simes is not alone in calling on the administration to reclaim the party’s pre-Reagan heritage—to abandon the moralistic, Wilsonian, neoconservative dream of exporting democracy and return to a more limited and realistic foreign policy that avoids the pitfalls of Iraq. 1. Dimitri K. Simes, “America’s Imperial Dilemma,” Foreign Affairs (Novem- ber/December 2003): 97, 100. Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative hberkc ch5 Mp_106 rev1 page 106 106 jacob heilbrunn In fact, critics on the Left and Right are remarkably united in their assessment of the administration. Both believe a neoconservative cabal has hijacked the administration’s foreign policy and has now overplayed its hand. -

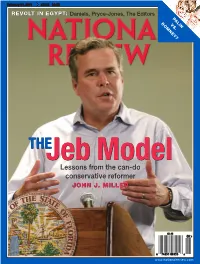

Lessons from the Can-Do Conservative Reformer JOHN J

2011_02_21 postal_cover61404-postal.qxd 2/1/2011 7:22 PM Page 1 February 21, 2011 49145 $3.95 REVOLT IN EGYPT: Daniels, Pryce-Jones, The Editors PALIN ROMNEY?VS. THEJebJeb Model Model Lessons from the can-do conservative reformer JOHN J. MILLER $3.95 08 0 74851 08155 6 www.nationalreview.com base_milliken-mar 22.qxd 2/1/2011 12:50 PM Page 1 ÊÊ ÊÊ 1 of Every 5 Homes and Businesses is Powered ÊÊ ÊÊ Ê by Reliable, Aordable Nuclear Energy. /VDMFBSFOFSHZTVQQMJFTPG"NFSJDBTFMFDUSJDJUZXJUIPVU U.S. Electricity Generation FNJUUJOHBOZHSFFOIPVTFHBTFT-BTUZFBS SFBDUPSTJO Fuel Shares Natural Gas TUBUFTQSPEVDFENPSFUIBOCJMMJPOLJMPXBUUIPVSTPG 23.3% FMFDUSJDJUZ KVTUTIZPGBSFDPSEZFBSGPSFMFDUSJDJUZHFOFSBUJPO GSPNOVDMFBSQPXFSQMBOUT/FXOVDMFBSFOFSHZGBDJMJUJFTBSF CFJOHCVJMUUPEBZUIBUXJMMCFBNPOHUIFNPTUDPTUFGGFDUJWF Nuclear 20.2% GPSDPOTVNFSTXIFOUIFZDPNFPOMJOF Coal Hydroelectric 44.6% Ê Ê Ê Ê Ê Ê Ê Ê ÊÊ ÊÊ Ê 5PNFFUPVSJODSFBTJOHEFNBOEGPSFMFDUSJDJUZ XFOFFEB 6.8% Renewables DPNNPOTFOTF CBMBODFEBQQSPBDIUPFOFSHZQPMJDZUIBUJODMVEFT Oil 1 and Other % 4.1% MPXDBSCPOTPVSDFTTVDIBTOVDMFBS XJOEBOETPMBSQPXFS Source: 2009, U.S. Energy Information Administration 7JTJUOFJPSHUPMFBSONPSF toc_QXP-1127940144.qxp 2/2/2011 1:23 PM Page 1 Ramesh Ponnuru on Palin vs. Romney Contents p. 24 FEBRUARY 21, 2011 | VOLUME LXIII, NO. 3 | www.nationalreview.com ON THE COVER Page 32 The Education Ex-Governor Jeb Bush is quietly building a legacy as something other than the Bush who didn’t reach the Oval Office. Governors BOOKS, ARTS everywhere boast of a desire to & MANNERS become ‘the education governor.’ 47 THE GILDED GUILD As Florida’s chief executive, Bush Robert VerBruggen reviews Schools really was one. John J. Miller for Misrule: Legal Academia and an Overlawyered America, by Walter Olson. COVER: CHARLES W. LUZIER/REUTERS/CORBIS 48 AUSTRALIAN MODEL ARTICLES Arthur W. -

Norman Podhoretz: a Biography"

Books Book Review: "Norman Podhoretz: A Biography" By Thomas L. Jeffers (Cambridge University Press). By Saul Rosenberg '93GSAS | Fall 2010 Norman Podhoretz, a maker of friends, ex-friends, and enemies. (David Howells / Corbis) John Gross, the English literary critic, was once in a magazine office in New York when the secretary called across the room to him: “John, there’s a Mr. Podhoretz on the phone for you.” As Gross recalled, “I felt every pair of eyes drilling into me, as though she’d said, ‘There’s a Mr. Himmler on the phone for you.’” This anecdote, retold by Thomas Jeffers in his Norman Podhoretz: A Biography, nicely sums up what many people feel about “Mr. Podhoretz.” He is hated by liberals for his turn to the right at the end of the sixties, and particularly loathed for his energetic support of Ronald Reagan, George W. Bush, and the Iraq War. So it is good someone should remind us, as Jeffers admiringly does, that Podhoretz is a first- class intellectual of enormous culture and considerable humanity. Podhoretz ’50CC was a first-generation American prodigy, an acute reader initially of literature and then politics, whose aggressive intellect took him from beat-up Brownsville through a glittering student career at Columbia College and Cambridge University to the editorship of Commentary at age 30. He edited the monthly from 1960 to 1995 into a publication The Economist once mused might be “the best magazine in the world.” In the last 25 years of his tenure, Podhoretz helped found and lead the neoconservative revolution that insisted, against some popular and much elite opinion, that America was, for all its faults, a clear force for good in the world. -

Andrew J. Bacevich

ANDREW J. BACEVICH Department of International Relations Boston University 152 Bay State Road Boston, Massachusetts 02215 Telephone (617) 358-0194 email: [email protected] CURRENT POSITION Boston University Professor of History and International Relations, College of Arts & Sciences Professor, Kilachand Honors College EDUCATION Princeton University, M. A., American History, 1977; Ph.D. American Diplomatic History, 1982 United States Military Academy, West Point, B.S., 1969 FELLOWSHIPS Columbia University, George McGovern Fellow, 2014 Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies, University of Notre Dame Visiting Research Fellow, 2012 The American Academy in Berlin Berlin Prize Fellow, 2004 The Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies, Johns Hopkins University Visiting Fellow of Strategic Studies, 1992-1993 The John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University National Security Fellow, 1987-1988 Council on Foreign Relations, New York International Affairs Fellow, 1984-1985 PREVIOUS APPOINTMENTS Boston University Director, Center for International Relations, 1998-2005 The Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies, Johns Hopkins University Professorial Lecturer; Executive Director, Foreign Policy Institute, 1993-1998 School of Arts and Sciences, Johns Hopkins University Professorial Lecturer, Department of Political Science, 1995-19 United States Military Academy, West Point Assistant Professor, Department of History, 1977-1980 1 PUBLICATIONS Books and Monographs Breach of Trust: How Americans Failed Their Soldiers and Their Country. New York: Metropolitan Books (2013); audio edition (2013). The Short American Century: A Postmortem. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press (2012). (editor) Washington Rules: America’s Path to Permanent War. New York: Metropolitan Books (2010); audio edition (2010); Chinese edition (2011); Korean edition (2013). The Limits of Power: The End of American Exceptionalism. -

George Orwell and the American Conservatives

Syracuse Scholar (1979-1991) Volume 6 Issue 1 Syracuse Scholar Spring 1985 Article 8 1985 George Orwell and the American Conservatives Gordon Beadle Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/suscholar Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Beadle, Gordon (1985) "George Orwell and the American Conservatives," Syracuse Scholar (1979-1991): Vol. 6 : Iss. 1 , Article 8. Available at: https://surface.syr.edu/suscholar/vol6/iss1/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Syracuse Scholar (1979-1991) by an authorized editor of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Beadle: George Orwell and the American Conservatives George Orwell and the American ConselVativ~ Gordon Beadle or almost four decades, George Orwell has been near the center Fof popular American political discourse. "Orwellian" and the familiar Orwellianisms of Animal Farm and 1984 are deeply rooted in the popular mind as symbols of state terror and tyranny, even among people who have never read Orwell. The enduring relevance of Orwell's warning and the almost universal fear of Big Brother no doubt reflect our growing fear that we may no longer be in control of the advanced technology we have created. Yet we never seem to locate Big Brother, and the manner in which we interpret, misinterpret, and reinterpret 1984 nearly always reflects the ebb and flow of the American political climate. This accounts for the strange fact that there are several politically incompatible American George Orwells. There is the usually ignored socialist George Orwell, and there is George Orwell, the cult figure of the liberal anti-Communist Left. -

N.J. Robinson Impossibilities No Longer Stood in the Way

My Affairs A MEMOIR OF THE MAGAZINE INDUSTRY (2016-2076) N.J. Robinson Impossibilities no longer stood in the way. One’s life had fattened on impossibilities. Before the boy was six years old, he had seen four impossibilities made actual—the ocean-steamer, the rail- way, the electric telegraph, and the Daguerreotype; nor could he ever learn which of the four had most hurried others to come… In 1850, science would have smiled at such a romance as this, but, in 1900, as far as history could learn, few men of science thought it a laughing matter. — The Education of Henry Adams I was emerging from these conferences amazed and exalted, con- vinced, one might say. It seemed to me that I traveled through Les Champs Elysées in a carriage pulled by two proud lions, turned into anti-lions, sweeter than lambs, only by the harmonic force; the dolphins and the whales, transformed into anti-dolphins and into anti-whales, made me sail gently on all the seas; the vul- tures, turned anti-vultures, carried me on their wings towards the heights of the heavens. Magnificent was the description of the beauties, the pleasures, and the delights of the spirit and the heart in the phalansterian city. — Ion Ghica My Affairs have been editing a magazine now for almost exactly sixty years. I hope to live a good while longer—life expectancy is shooting up so fast that now, at age eighty- Iseven, I may still not have reached my halfway point. Yet sixty is the sort of number that leads one to reflect. -

![I Ll]!Ijjljjl]IIIIII NEU Majed Keshta: Values and Beliefs of American Foreign Policy in the Middle East](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0854/i-ll-ijjljjl-iiiiii-neu-majed-keshta-values-and-beliefs-of-american-foreign-policy-in-the-middle-east-2110854.webp)

I Ll]!Ijjljjl]IIIIII NEU Majed Keshta: Values and Beliefs of American Foreign Policy in the Middle East

1988 NEAR EAST UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF APPLIED AND SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS Values and Beliefs of American Foreign Policy in the Middle East MASTER THESIS BY Majed M. Said Keshta Nicosia 2005 I ll]!IJjlJJl]IIIIII NEU Majed Keshta: Values and Beliefs of American Foreign Policy in the Middle East We certify that this thesis is satisfactory for the award of a degree of Master of Arts in International Relations Examining Committee in charge Prof. Dr. Jouni Suistola Dean of the Faculty of Economic and Administrative Sciences (Supervisor). Assoc. Prof. Dr. Zeliha Khashman Chairman oflntemational Relations Department. Chair of the Committee. Assist. Prof. Dr. Ali Dayioglu Department of International Relations. NEAR EAST UNIVERSITY FACULTY OF ECONOMICS AND ADMINISTRATIVE SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS JURY REPORT ACADEMIC YEAR: 2004-2005 STUDENT INFORMATION Full Name: Majed M. Said Keshta Nationality: Palestinian Institution: Near East University. Department: International Relations THESIS Title: Values and Beliefs of American Foreign Policy in the Middle East Description: This thesis is intended to portray how values and beliefs toward foreign affairs have changed over the course of the history of American Republic and how U.S. foreign policy toward the Middle East has thus changed from the World War 1 years through the shock of September 11 attacks and beyond within values contexts. Supervisor Prof. Dr. Jouni Suistola JURY'S DECISION The Jury has been accepted by all Jury's members unanimously. JURY MEMBERS Number attending I Date I 31131200s Name: Signature Prof.Dr. Jouni Souistola .......-:::::~ ,,..,, Assoc. Prof. Dr. Zeliha Khashman 9 - ~ • ~ h/11,r II .r'I /2.. -

Podhoretz's Complaint

This article originally appeared in Democracy: A Journal of Ideas http://www.democracyjournal.org/article.php?ID=6575 © Democracy: A Journal of Ideas, Inc., 2007 anne-marie slaughter Podhoretz’s Complaint Neoconservatism has failed. How liberal internationalism can triumph in its place. world war iV: the long struggle against islamofascism By norman podhoretz • douBleday • 2007 • 240 pages • $24.95 aligned by all, deserted even by many of his closest associates, GeorgeM W. Bush is actually a visionary. He is one of the few Americans and global leaders who “possessed the wit to see the future” after September 11 and “summoned up the courage to begin crossing over into it.” That is the world according to Norman Podhoretz in his new book, World War IV: The Long Struggle Against Islamofascism. Podhoretz is nothing if not tendentious; he is supremely sure of himself and speaks in absolutes—much like George W. Bush. The result is a lively but often infuriating book that will tempt many readers to counterpunch at every turn against its intemperate excess. Journalists may take offense at his insistence that coverage of the Iraq war demonstrates how “the Vietnam syndrome—the ‘loss of self-confidence and the concomitant spread of neo-isolationist and pacifist anne-marie slaughter is the dean of the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs at Princeton University and author of The Idea That Is America. democracyjournal.org 73 anne-marie slaughter sentiment’” across America—is “still alive and well.” Historians may wonder at his certainty that the Vietnam War was popularly supported and all but won, had defeatist elites not lost their nerve. -

George Orwell and the Cold War: a Reconsideration

GEORGE ORWELL AND THE COLD WAR: A RECONSIDERATION Murray N. Rothbard Reflections on America, 1984: An Orwell Symposium. Ed. Robert Mulvihill. Athens and London, University of Georgia Press. 1986. In a recent and well-known article, Norman Podhoretz has attempted to conscript George Orwell into the ranks of neoconservative enthusiasts for the newly revitalized cold war with the Soviet Union.[1] If Orwell were alive today, this truly "Orwellian" distortion would afford him considerable wry amusement. It is my contention that the cold war, as pursued by the three superpowers of Nineteen Eighty -Four, was the key to their successful imposition of a totalitarian regime upon their subjects. We all know that Nineteen Eighty-Four was a brilliant and mordant attack on totalitarian trends in modern society, and it is also clear that Orwell was strongly opposed to communism and to the regime of the Soviet Union. But the crucial role of a perpetual cold war in the entrenchment of totalitarianism in Orwell?s "nightmare vision" of the world has been relatively neglected by writers and scholars. In Nineteen Eighty-Four there are three giant superstates or blocs of nations: Oceania (run by the United States, and including the British Empire and Latin America), Eurasia (the Eurasian continent), and Eastasia (China, southeast Asia, much of the Pacific), The superpowers are always at war, in shifting coalitions and alignments against each other. The war is kept, by agreement between the superpowers, safely on the periphery of the blocs, since war in their heartlands might actually blow up the world and their own rule along with it.