Baltimore County Tmdl Implementation Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gunpowder River

Table of Contents 1. Polluted Runoff in Baltimore County 2. Map of Baltimore County – Percentage of Hard Surfaces 3. Baltimore County 2014 Polluted Runoff Projects 4. Fact Sheet – Baltimore County has a Problem 5. Sources of Pollution in Baltimore County – Back River 6. Sources of Pollution in Baltimore County – Gunpowder River 7. Sources of Pollution in Baltimore County – Middle River 8. Sources of Pollution in Baltimore County – Patapsco River 9. FAQs – Polluted Runoff and Fees POLLUTED RUNOFF IN BALTIMORE COUNTY Baltimore County contains the headwaters for many of the streams and tributaries feeding into the Patapsco River, one of the major rivers of the Chesapeake Bay. These tributaries include Bodkin Creek, Jones Falls, Gwynns Falls, Patapsco River Lower North Branch, Liberty Reservoir and South Branch Patapsco. Baltimore County is also home to the Gunpowder River, Middle River, and the Back River. Unfortunately, all of these streams and rivers are polluted by nitrogen, phosphorus and sediment and are considered “impaired” by the Maryland Department of the Environment, meaning the water quality is too low to support the water’s intended use. One major contributor to that pollution and impairment is polluted runoff. Polluted runoff contaminates our local rivers and streams and threatens local drinking water. Water running off of roofs, driveways, lawns and parking lots picks up trash, motor oil, grease, excess lawn fertilizers, pesticides, dog waste and other pollutants and washes them into the streams and rivers flowing through our communities. This pollution causes a multitude of problems, including toxic algae blooms, harmful bacteria, extensive dead zones, reduced dissolved oxygen, and unsightly trash clusters. -

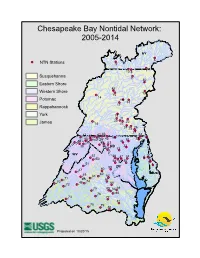

Chesapeake Bay Nontidal Network: 2005-2014

Chesapeake Bay Nontidal Network: 2005-2014 NY 6 NTN Stations 9 7 10 8 Susquehanna 11 82 Eastern Shore 83 Western Shore 12 15 14 Potomac 16 13 17 Rappahannock York 19 21 20 23 James 18 22 24 25 26 27 41 43 84 37 86 5 55 29 85 40 42 45 30 28 36 39 44 53 31 38 46 MD 32 54 33 WV 52 56 87 34 4 3 50 2 58 57 35 51 1 59 DC 47 60 62 DE 49 61 63 71 VA 67 70 48 74 68 72 75 65 64 69 76 66 73 77 81 78 79 80 Prepared on 10/20/15 Chesapeake Bay Nontidal Network: All Stations NTN Stations 91 NY 6 NTN New Stations 9 10 8 7 Susquehanna 11 82 Eastern Shore 83 12 Western Shore 92 15 16 Potomac 14 PA 13 Rappahannock 17 93 19 95 96 York 94 23 20 97 James 18 98 100 21 27 22 26 101 107 24 25 102 108 84 86 42 43 45 55 99 85 30 103 28 5 37 109 57 31 39 40 111 29 90 36 53 38 41 105 32 44 54 104 MD 106 WV 110 52 112 56 33 87 3 50 46 115 89 34 DC 4 51 2 59 58 114 47 60 35 1 DE 49 61 62 63 88 71 74 48 67 68 70 72 117 75 VA 64 69 116 76 65 66 73 77 81 78 79 80 Prepared on 10/20/15 Table 1. -

This Special Bulletin Brings to You the Summary and Recommendations of the Whitman, Requardt and Associates Report on Lake Rolan

SPECIAL REPORT FROM Associates, Engineers, to do an engineering study on how THE LAKE ROLAND WATERSHED FOUNDATION, INC. best to remove silt now clogging the Lake, and collecting daily at a rapid rate. This study was authorized by Baltimore This special Bulletin brings to you the Summary and City and Baltimore County. Recommendations of the Whitman, Requardt and Associates (2) The offer of free dredging services for two months by report on Lake Roland, published in July, 1974. We are Ellicott Machine Corporation, and reduced labor-operating grateful to Mr. Douglas L. Tawney, Director, Baltimore City costs by C. J. Langenfelder & Company and the Operating Bureau of Recreation and Parks, for permission to do this. Engineers Union. We alsoprovide you with a map showing where the planned (3) Theformation of a tax-exempt, non-profit community basins will be and the location of the spoil areas. organization, under the auspices of the Ruxton-Riderwood We ask you to read this carefully so that you will know the Improvement Association, known as The Lake Roland facts when the community meeting is held Monday evening, Watershed Foundation, Inc. The Foundation will act as a September 30, in the Auditorium of the Church of the Good voice for the community, and will work to insure that any Shepherd, Boyce Avenue, Ruxton, at 8P.M. At this time, Mr. conservation program for Lake Roland is carefully and John B. Gillett of Whitman, Requardt and Associates, will sensitively executed. present the project and will try to answer any questions you (4) Expression of interest in the designation of Lake may have. -

Upstream, Downstream from Good Intentions to Cleaner Waters

Upstream, Downstream From Good Intentions to Cleaner Waters A Ground-Breaking Study of Public Attitudes Toward Stormwater in the Baltimore Area Sponsored by the Herring Run Watershed Association and the Jones Falls Watershed Association OpinionWorks / 2008 OpinionWorks Stormwater Action Coalition The Stormwater Action Coalition is a subgroup of the Watershed Advisory Group (WAG). WAG is an informal coalition of about 20 organizations from the Baltimore Metropolitan area who come together from time to time to interact with local government on water quality issues. WAG members represent all the region’s streams and waters and recently pressed the city and county to include stormwater as one of the five topics in the 2006 Baltimore City/Baltimore County Watershed Agreement. The Stormwater Action Coalition is focused on raising public awareness about the problems caused by contaminated urban runoff. Representa- tives of the following organizations have participated in Stormwater Action Coalition activities: Alliance for the Chesapeake Bay Baltimore Harbor Watershed Association Center for Watershed Protection Chesapeake Bay Foundation Clean Water Action Environment Maryland Friends of the Patapsco Valley Gunpowder Valley Conservancy Gwynns Falls Watershed Association Herring Run Watershed Association Jones Falls Watershed Association Parks & People Foundation Patapsco/Back River Tributary Team Prettyboy Watershed Alliance Watershed 263 We extend our appreciation to our local government colleagues: Baltimore City Department of Public Works Baltimore City Department of Planning Baltimore County Department of Environmental Protection and Resource Management Baltimore Metropolitan Council And to our funders: The Keith Campbell Foundation for the Environment The Rauch Foundation The Abell Foundation The Baltimore Community Foundation The Cooper Family Fund and the Cromwell Family Fund at the Baltimore Community Foundation More than half of the study participants strongly agree that they would do more, if they just knew what to do. -

The Chesapeake Bay Trust

The Chesapeake Bay Trust Working to promote public awareness and participation in the restoration and protection of the Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries Annual Report 2003 From the Chairman Dear Friends of the Chesapeake Bay, With the help of many partners, volunteers, and donors, 2003 has been a terrific year for the Chesapeake Bay Trust. In 2003, the Trust was pleased to award more than $1.8 million in grants to nonprofit organizations, community groups, schools, and public agencies—an increase of nearly 50 percent from the previous year. This marks the highest level of annual grantmaking in the Trust’s 18-year history. Through this ambitious year of grantmaking, the Trust has supported hundreds of projects that benefit the Bay and involve the citizens of Maryland in the process. Trust grants helped plant stream- side forests to reduce water pollution and create important wildlife habitat. They supported innovative streambank stabilization projects—called “living shorelines”—that absorb polluted run-off and reestablish fish and crab habitat. And Trust grants gave thousands of Maryland students a greater appreciation for the Bay through hands-on experiences like skipjack trips and schoolyard habitat projects. The following pages detail these and other projects supported by the Trust at locations throughout the state. This report also summarizes other notable Trust activities in 2003, including a new scholarship, an urban watershed grant program, and a new design for the popular Treasure the Chesapeake license plate. In 2003, the Trust made significant strides in advancing its mission to promote public awareness and participation in the restoration and protection of the Chesapeake Bay and its rivers. -

Maryland Stream Waders 10 Year Report

MARYLAND STREAM WADERS TEN YEAR (2000-2009) REPORT October 2012 Maryland Stream Waders Ten Year (2000-2009) Report Prepared for: Maryland Department of Natural Resources Monitoring and Non-tidal Assessment Division 580 Taylor Avenue; C-2 Annapolis, Maryland 21401 1-877-620-8DNR (x8623) [email protected] Prepared by: Daniel Boward1 Sara Weglein1 Erik W. Leppo2 1 Maryland Department of Natural Resources Monitoring and Non-tidal Assessment Division 580 Taylor Avenue; C-2 Annapolis, Maryland 21401 2 Tetra Tech, Inc. Center for Ecological Studies 400 Red Brook Boulevard, Suite 200 Owings Mills, Maryland 21117 October 2012 This page intentionally blank. Foreword This document reports on the firstt en years (2000-2009) of sampling and results for the Maryland Stream Waders (MSW) statewide volunteer stream monitoring program managed by the Maryland Department of Natural Resources’ (DNR) Monitoring and Non-tidal Assessment Division (MANTA). Stream Waders data are intended to supplementt hose collected for the Maryland Biological Stream Survey (MBSS) by DNR and University of Maryland biologists. This report provides an overview oft he Program and summarizes results from the firstt en years of sampling. Acknowledgments We wish to acknowledge, first and foremost, the dedicated volunteers who collected data for this report (Appendix A): Thanks also to the following individuals for helping to make the Program a success. • The DNR Benthic Macroinvertebrate Lab staffof Neal Dziepak, Ellen Friedman, and Kerry Tebbs, for their countless hours in -

Analysis of the Jones Falls Sewershed

GREEN TOWSON ALLIANCE WHITE PAPER ON SEWERS AUGUST 31, 2017 IS RAW SEWAGE CONTAMINATING OUR NEIGHBORHOOD STREAMS? ANALYISIS OF THE JONES FALLS SEWERSHED ADEQUATE PUBLIC SEWER TASK FORCE OF THE GREEN TOWSON ALLIANCE: Larry Fogelson, Retired MD State Planner, Rogers Forge Resident Tom McCord, Former CFO, and MD Industry CPA, Ruxton Resident Roger Gookin, Retired Sewer Contractor, Towsongate Resident JONES FALLS SEWER SYSTEM INVESTIGATION AND REPORT It is shocking that in the year 2017, human waste is discharged into open waters. The Green Towson Alliance (GTA) believes the public has a right to know that continuing problems with the Baltimore County sanitary sewer system are probably contributing to dangerous bacteria in Lake Roland and the streams and waterways that flow into it. This paper is the result of 15 months of inquiries and analysis of information provided by the County and direct observations by individuals with expertise in various professional disciplines related to this topic. GTA welcomes additional information that might alter our analysis and disprove our findings. To date, the generalized types of responses GTA has received to questions generated by our analysis do not constitute proof, or provide assurance, that all is well. 1. The Adequate Public Sewer Task Force of the Green Towson Alliance: The purpose of this task force is to protect water quality and public health by promoting the integrity and adequacy of the sanitary sewer systems that serve the Towson area. It seeks transparency by regulators and responsible officials to assure that the sewerage systems are properly planned, maintained, and operated in a manner that meets the requirements of governing laws and regulations. -

Gwynns Falls/Leakin Park to Middle Branch Park Hanover Street Bridge

When complete, the 35-mile Baltimore Greenway Trails Network will connect the city’s anchor institutions and destinations with Baltimore’s diverse communities. For more information, go to railstotrails.org/Baltimore. View and download a full map of the trail network route: rtc.li/baltimore_map-footprint. Gwynns Falls/Leakin Park to Middle Branch Park Western Loop Segment This mostly complete section of the loop heads southeast on the Gwynns Falls Trail from Gwynns Falls/Leakin park— one of the largest urban parks/forests in the country—to Middle Branch Park, with a further connection to Cherry Hill Park further south. On its way, it connects a number of historically significant neighborhoods and parks, the oldest railroad trestle in the country, the B&O Museum and roundhouse (the birthplace of the railroad in America), St. Agnes Hospital and many other historical destinations. Hanover Street Bridge to Canton Southern Loop Segment The loop segment extends from Hanover Street Bridge—on the southern side of the Middle Branch of the Patapsco River—north to Port Covington. A large- scale planning and redevelopment project at Port Covington for Under Armour’s world headquarters is Baltimore Department of Recreation and Parks Bike Around Program Photo by Molly Gallant underway, which will include public shoreline access and the connecting of both sides of the river via a disused railroad trestle. The corridor travels through one of the Canton to Herring Run Southeast Loop Segment last undeveloped sections of the Baltimore shoreline, provides great views of the city skyline and passes by This segment of the project involves the transformation many historical sites. -

7Hstorr Trails Baltimore County Histrical Society

7hstorr Trails Baltimore County Histrical Society Agriculture Building 9811 Van Buren Lane Cockeysville, Md. 21030 ISSN 0889-6186 Editors: JOHN W. McGRAIN and WILLIAM HOLLIFIEED VOL. 26 AUTUMN 1991-WINTER 1991-92 NO. 1 & NO. 2 The Romantic -ynn's Falls Valley George E. Tack Introduction The following article about the Gwynns Falls Valley appeared in the August 1907 issue of MarylandMonthly Magazine, published by Henry Quarles Nicholson. At that time, much of the Gwynns Falls Valley was in the city of Baltimore, acquired from the county as a result of the annexation of 1888. The county line was just west of the intersection of Franklintown and Wetheredville Roads. After Tack's article, in 1918, the boundary was again moved westward and more of the Gwynns Falls Valley, including the village of Dickeyville and Leakin Park, was incorporated into the city. George E. Tack was born in 1873 and lived most of his life, at least up to 1918, in West Baltimore. In 1900 he lived with his parents, two brothers, and a sister. His father, born in Germany, was a clerk. George was then a clerk for a steamship company. Baltimore directories show a variety of occupations for him: frame maker (1893), solicitor (1898-1900), painter (1901), nurse (1903), clerk (1910, 1913), and nurse (1916-1918). Interestingly, he was listed as a poet in 1911. His interest in poetry is reflected in his style of writing and his inclusion of Folger McKinsey's poem at the end of the Gwynns Falls Valley article. An example of his own poetry, about a winter rainbow over Glyndon, had appeared in Maryland Monthly Magazine earlier in 1907. -

Neighborhood News Summer 2010 Summer

Neighborhood News Summer 2010 Summer Ruxton-Riderwood-Lake Roland Area Improvement Association springs. As the Flynn family drove to one of Jack’s Toad Haul lacrosse games, Kevin described their experience via car phone, with Jack chiming in from the back seat. INSIDE by Bliss McCord It seems that each spring hundreds, perhaps One rainy night this Three Ways to thousands, of toads make spring, as I was Help the Bay winding my way home their annual migration from down the Bellona Towson Run to Lake Roland, Page 3 looking for true love. They Avenue hill, my heart Election sank. Down at the used to swim through the Information bottom were the culvert where Towson Run is telltale signs of a car piped under Bellona. For at Page 4 accident: flashing least 15 years now, however, Home Sales hazard lights, orangey- siltation has forced the red highway cones, toads to go overland across Page 6 men with flashlights. the road. The resultant Judging by the amount carnage gave birth to a new Blakehurst Hosts of activity, I worried volunteer movement, what Board Meeting & that the accident might we are calling The Toad Legislative be serious. Brigade. Woe to the toad Wrap Up who tries crossing without As I was waved around its help. Toad escorting Page 8 the cones by someone is not unique to Towson. Winner of Azalea who looked like The In Philadelphia, parts of House Award Fisherman from the Port Royal Avenue and Eva Gorton’s ads, my eyes Street are closed annually so Page 9 darted to the right, that local toads can make Stream drawn by more lights their way from the hills of Clean Up 2010 well off the road. -

Baltimore Metro Area

PHOTOS BY JUSTIN TSUCALAS, JASON VARNEY AND KEN STANEK FOR VISIT BALTIMORE VISIT FOR STANEK KEN AND VARNEY JASON TSUCALAS, JUSTIN BY PHOTOS Call 443.278.4701 443.278.4701 Call whole or in part is strictly prohibited. prohibited. strictly is part in or whole Available from 8 a.m. – 8:30 p.m., seven days a week a days seven p.m., 8:30 – a.m. 8 from Available consequences arising from errors or omissions. All rights reserved. Reproduction in in Reproduction reserved. rights All omissions. or errors from arising consequences Waterfront Partnership Guides Partnership Waterfront the accuracy of the information it publishes, but cannot be held responsible for any any for responsible held be cannot but publishes, it information the of accuracy the Visit Baltimore and Today Media Custom Communications make every effort to ensure ensure to effort every make Communications Custom Media Today and Baltimore Visit after hours. after Call 410.244.1030 during business hours, or 410.802.9631 410.802.9631 or hours, business during 410.244.1030 Call TodayMediaCustom.com Available from 10 a.m.– 10:30 p.m., seven days a week a days seven p.m., 10:30 a.m.– 10 from Available 410-828-0120 Downtown Partnership Guides Partnership Downtown Baltimore, MD 21211 21211 MD Baltimore, 1014 W. 36th Street Street 36th W. 1014 your Downtown, Inner Harbor or Harbor East destination. East Harbor or Harbor Inner Downtown, your Guides will meet you at your location and walk with you to to you with walk and location your at you meet will Guides Custom Communications Custom on foot and are the “eyes and ears” of the community. -

Real Stories Baltimore County History

REAL STORIES FROM BALTIMORE COUNTY HISTORY Data Obtained hvJ the Teachers and Children of Baltimore County (Maryland) Schools IDustrated with drawings by 7th and 8th Grade Pupils Revised and Adapted by ISOBEL DAVIDSON, Supercisor of Primary Grades, Baltimore County School.s. ---0--- BALTIMORE WARWICK & YORK, INC. 1917. Copyrighted, 1917, by· WARWICK & YORK, INc. REAL STORIES FROM BALTIMORE COUNTY HISTORY CONTENTS Page A FOREWORD ················~···························~---························ . 1 I. ONCE UPON A TIME IN OUR., ~OMMUNITY 1. Neighborhood Changes ....... .-........................................ 5 2. Our Country Long ~,g-0................................................ 9 3. Indians of Marylat'lct: Susquehannoughs and Al- gonqu1ns ......................................... .. ......................... 10 4. Con1ing of the First White 1'Ian-Captain John Smith in the Chesapeake . .: ........................ ~............. 13 5. How Maryland Was Named ........................................ 16 II. ONCE UPON A TIME IN BALTIMORE COUNTY 1. The Changing Boundary Line...................................... 19 2. The Early Pioneers...................................................... 20 3. Colonial Times .............................................................. 22 4. County Seats: Old Baltimore, Foster's Neck, Joppa, Baltimore Town, Towson ........................................ 37 III. ONCE UPON A TIME IN BALTIMORE TowN ........................ 46 IV. ONcE UPON A TIME IN OuR TowN AND V1c1NITY 1. Green Spring. Valley-1743.........................................