Upstream, Downstream from Good Intentions to Cleaner Waters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gunpowder River

Table of Contents 1. Polluted Runoff in Baltimore County 2. Map of Baltimore County – Percentage of Hard Surfaces 3. Baltimore County 2014 Polluted Runoff Projects 4. Fact Sheet – Baltimore County has a Problem 5. Sources of Pollution in Baltimore County – Back River 6. Sources of Pollution in Baltimore County – Gunpowder River 7. Sources of Pollution in Baltimore County – Middle River 8. Sources of Pollution in Baltimore County – Patapsco River 9. FAQs – Polluted Runoff and Fees POLLUTED RUNOFF IN BALTIMORE COUNTY Baltimore County contains the headwaters for many of the streams and tributaries feeding into the Patapsco River, one of the major rivers of the Chesapeake Bay. These tributaries include Bodkin Creek, Jones Falls, Gwynns Falls, Patapsco River Lower North Branch, Liberty Reservoir and South Branch Patapsco. Baltimore County is also home to the Gunpowder River, Middle River, and the Back River. Unfortunately, all of these streams and rivers are polluted by nitrogen, phosphorus and sediment and are considered “impaired” by the Maryland Department of the Environment, meaning the water quality is too low to support the water’s intended use. One major contributor to that pollution and impairment is polluted runoff. Polluted runoff contaminates our local rivers and streams and threatens local drinking water. Water running off of roofs, driveways, lawns and parking lots picks up trash, motor oil, grease, excess lawn fertilizers, pesticides, dog waste and other pollutants and washes them into the streams and rivers flowing through our communities. This pollution causes a multitude of problems, including toxic algae blooms, harmful bacteria, extensive dead zones, reduced dissolved oxygen, and unsightly trash clusters. -

This Special Bulletin Brings to You the Summary and Recommendations of the Whitman, Requardt and Associates Report on Lake Rolan

SPECIAL REPORT FROM Associates, Engineers, to do an engineering study on how THE LAKE ROLAND WATERSHED FOUNDATION, INC. best to remove silt now clogging the Lake, and collecting daily at a rapid rate. This study was authorized by Baltimore This special Bulletin brings to you the Summary and City and Baltimore County. Recommendations of the Whitman, Requardt and Associates (2) The offer of free dredging services for two months by report on Lake Roland, published in July, 1974. We are Ellicott Machine Corporation, and reduced labor-operating grateful to Mr. Douglas L. Tawney, Director, Baltimore City costs by C. J. Langenfelder & Company and the Operating Bureau of Recreation and Parks, for permission to do this. Engineers Union. We alsoprovide you with a map showing where the planned (3) Theformation of a tax-exempt, non-profit community basins will be and the location of the spoil areas. organization, under the auspices of the Ruxton-Riderwood We ask you to read this carefully so that you will know the Improvement Association, known as The Lake Roland facts when the community meeting is held Monday evening, Watershed Foundation, Inc. The Foundation will act as a September 30, in the Auditorium of the Church of the Good voice for the community, and will work to insure that any Shepherd, Boyce Avenue, Ruxton, at 8P.M. At this time, Mr. conservation program for Lake Roland is carefully and John B. Gillett of Whitman, Requardt and Associates, will sensitively executed. present the project and will try to answer any questions you (4) Expression of interest in the designation of Lake may have. -

Maryland Stream Waders 10 Year Report

MARYLAND STREAM WADERS TEN YEAR (2000-2009) REPORT October 2012 Maryland Stream Waders Ten Year (2000-2009) Report Prepared for: Maryland Department of Natural Resources Monitoring and Non-tidal Assessment Division 580 Taylor Avenue; C-2 Annapolis, Maryland 21401 1-877-620-8DNR (x8623) [email protected] Prepared by: Daniel Boward1 Sara Weglein1 Erik W. Leppo2 1 Maryland Department of Natural Resources Monitoring and Non-tidal Assessment Division 580 Taylor Avenue; C-2 Annapolis, Maryland 21401 2 Tetra Tech, Inc. Center for Ecological Studies 400 Red Brook Boulevard, Suite 200 Owings Mills, Maryland 21117 October 2012 This page intentionally blank. Foreword This document reports on the firstt en years (2000-2009) of sampling and results for the Maryland Stream Waders (MSW) statewide volunteer stream monitoring program managed by the Maryland Department of Natural Resources’ (DNR) Monitoring and Non-tidal Assessment Division (MANTA). Stream Waders data are intended to supplementt hose collected for the Maryland Biological Stream Survey (MBSS) by DNR and University of Maryland biologists. This report provides an overview oft he Program and summarizes results from the firstt en years of sampling. Acknowledgments We wish to acknowledge, first and foremost, the dedicated volunteers who collected data for this report (Appendix A): Thanks also to the following individuals for helping to make the Program a success. • The DNR Benthic Macroinvertebrate Lab staffof Neal Dziepak, Ellen Friedman, and Kerry Tebbs, for their countless hours in -

The Patapsco Regional Greenway the Patapsco Regional Greenway

THE PATAPSCO REGIONAL GREENWAY THE PATAPSCO REGIONAL GREENWAY ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS While the Patapsco Regional Greenway Concept Plan and Implementation Matrix is largely a community effort, the following individuals should be recognized for their input and contribution. Mary Catherine Cochran, Patapsco Heritage Greenway Dan Hudson, Maryland Department of Natural Resources Rob Dyke, Maryland Park Service Joe Vogelpohl, Maryland Park Service Eric Crawford, Friends of Patapsco Valley State Park and Mid-Atlantic Off-Road Enthusiasts (MORE) Ed Dixon, MORE Chris Eatough, Howard County Office of Transportation Tim Schneid, Baltimore Gas & Electric Pat McDougall, Baltimore County Recreation & Parks Molly Gallant, Baltimore City Recreation & Parks Nokomis Ford, Carroll County Department of Planning The Patapsco Regional Greenway 2 THE PATAPSCO REGIONAL GREENWAY TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION .................................................4 2 BENEFITS OF WALKING AND BICYCLING ...............14 3 EXISTING PLANS ...............................................18 4 TREATMENTS TOOLKIT .......................................22 5 GREENWAY MAPS .............................................26 6 IMPLEMENTATION MATRIX .................................88 7 FUNDING SOURCES ...........................................148 8 CONCLUSION ....................................................152 APPENDICES ........................................................154 Appendix A: Community Feedback .......................................155 Appendix B: Survey -

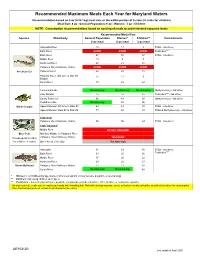

Recommended Maximum Fish Meals Each Year For

Recommended Maximum Meals Each Year for Maryland Waters Recommendation based on 8 oz (0.227 kg) meal size, or the edible portion of 9 crabs (4 crabs for children) Meal Size: 8 oz - General Population; 6 oz - Women; 3 oz - Children NOTE: Consumption recommendations based on spacing of meals to avoid elevated exposure levels Recommended Meals/Year Species Waterbody General PopulationWomen* Children** Contaminants 8 oz meal 6 oz meal 3 oz meal Anacostia River 15 11 8 PCBs - risk driver Back River AVOID AVOID AVOID Pesticides*** Bush River 47 35 27 PCBs - risk driver Middle River 13 9 7 Northeast River 27 21 16 Patapsco River/Baltimore Harbor AVOID AVOID AVOID American Eel Patuxent River 26 20 15 Potomac River (DC Line to MD 301 1511 9 Bridge) South River 37 28 22 Centennial Lake No Advisory No Advisory No Advisory Methylmercury - risk driver Lake Roland 12 12 12 Pesticides*** - risk driver Liberty Reservoir 96 48 48 Methylmercury - risk driver Tuckahoe Lake No Advisory 93 56 Black Crappie Upper Potomac: DC Line to Dam #3 64 49 38 PCBs - risk driver Upper Potomac: Dam #4 to Dam #5 77 58 45 PCBs & Methylmercury - risk driver Crab meat Patapsco River/Baltimore Harbor 96 96 24 PCBs - risk driver Crab "mustard" Middle River DO NOT CONSUME Blue Crab Mid Bay: Middle to Patapsco River (1 meal equals 9 crabs) Patapsco River/Baltimore Harbor "MUSTARD" (for children: 4 crabs ) Other Areas of the Bay Eat Sparingly Anacostia 51 39 30 PCBs - risk driver Back River 33 25 20 Pesticides*** Middle River 37 28 22 Northeast River 29 22 17 Brown Bullhead Patapsco River/Baltimore Harbor 17 13 10 South River No Advisory No Advisory 88 * Women = of childbearing age (women who are pregnant or may become pregnant, or are nursing) ** Children = all young children up to age 6 *** Pesticides = banned organochlorine pesticide compounds (include chlordane, DDT, dieldrin, or heptachlor epoxide) As a general rule, make sure to wash your hands after handling fish. -

Stopping the Flood Beneath Baltimore's Streets

Stopping the Flood Beneath Baltimore’s Streets The city’s failure to comply with a federal sewage consent decree, and how delay harms homeowners and the Inner Harbor DECEMBER 15, 2015 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Funded by the Abell Foundation. This report was researched and written by Tom Pelton, Courtney Bernhardt, Kira Burkhart, and Sylvia Lam of the Environmental Integrity Project. THE ENVIRONMENTAL INTEGRITY PROJECT The Environmental Integrity Project (http://www.environmentalintegrity.org) is a nonpartisan, nonprofit organization established in March of 2002 by former EPA enforcement attorneys to advocate for effective enforcement of environmental laws. EIP has three goals: 1) to provide objective analyses of how the failure to enforce or implement environmental laws increases pollution and affects public health; 2) to hold federal and state agencies, as well as individual corporations, accountable for failing to enforce or comply with environmental laws; and 3) to help local communities obtain the protection of environmental laws. For questions about this report, please contact EIP Director of Communications Tom Pelton at (202) 888-2703 or [email protected]. EXPLORE THE INTERACTIVE MAP http://arcg.is/1NGm2x3 PHOTOS: Cover: Sewage overflow , Falls Road, Baltimore Page 1: iStock Pages 3, 8, 16 (top), 17, back cover: Tom Pelton Pages 6, 11: Photos by Fern Shen for Baltimore Brew, with permission. https://www.baltimorebrew.com/ Page 16 (bottom): Doris Brightful Page 18: Brenda Johnson Executive Summary n 2002, the U.S. Justice Department sued Baltimore over a chronic problem: the city’s leaky, overloaded sewer system was routinely and illegally releasing tens of millions of I gallons of raw human waste into urban streams, the Inner Harbor, and Chesapeake Bay. -

Total Maximum Daily Load of Sediment in the Jones Falls Watershed, Baltimore City and Baltimore County, Maryland

Total Maximum Daily Load of Sediment in the Jones Falls Watershed, Baltimore City and Baltimore County, Maryland FINAL DEPARTMENT OF THE ENVIRONMENT 1800 Washington Boulevard, Suite 540 Baltimore, Maryland 21230-1718 Submitted to: Watershed Protection Division U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Region III 1650 Arch Street Philadelphia, PA 19103-2029 September 2011 EPA Submittal Date: September 28, 2009 EPA Approval Date: September 29, 2011 Jones Falls Sediment TMDL Document Version: 9/29/2011 FINAL Table of Contents List of Figures..................................................................................................................... ii List of Tables ...................................................................................................................... ii List of Abbreviations ......................................................................................................... iii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................ v 1.0 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................ 1 2.0 SETTING AND WATER QUALITY DESCRIPTION ............................................... 3 2.1 General Setting ...................................................................................................... 3 2.1.1. Land Use..................................................................................................... 5 2.2 Source Assessment ............................................................................................... -

Keep Maryland Beautiful Award Recipients

Protecting Land Forever Keep Maryland Beautiful Award Recipients Fiscal Year 2019 Bill James Environmental Grants Historic Sotterley, Inc Howard County Antique Farm Machinery Club Mountain Laurel Garden Club North County High School Pocomoke Middle School Clean Up & Green Up Maryland Grants African American Firefighters Historical Society Alice Ferguson Foundation Allegany County Commissioners & the Allegany County Solid Waste Management Board Annapolis Arts District Annapolis Green, Inc. Antietam-Conococheague Watershed Alliance Back River Restoration Committee, Inc. Banner Neighborhoods Bel Air Downtown Alliance Bethesda Green Beyond the Classroom, Inc. Brunswick Main Street, Inc. BUILD - Rebuild Johnston Square Neighborhood Org C.A.R.E Community Association, Inc Centreville Main Street Town of Centreville City of Greenbelt Department of Public Works Downtown Frederick Partnership Downtown Sykesville Connection at the Community Foundation of Carroll County Druid Heights Community Development Corporation Dundalk Renaissance Corporation Elkton Alliance, Inc. Fusion Partnerships, Inc. (Whitelock Community Farm) Galena Tree and Park Committee Havre de Grace Citizens Against Trash Historic Frostburg - a Maryland Main Street Community Howard County Conservancy I'm Still Standing By Grace Intersection of Change, Inc. Let's Beautify Cumberland! Main Street Historic Chestertown Main Street Middletown, MD Inc Main Street Princess Anne Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments Milton Montford Montgomery Parks Foundation Park Heights Renaissance Pigtown Main Street, Inc. Sandtown South Neighborhood Alliance Southeast Community Development Corporation Strong City Baltimore Takoma/Langley Crossroads Development Authority, Inc. The 6th Branch The Town of Colmar Manor Town of Emmitsburg Town of Manchester Town of Oakland Town of Thurmont & Main Street Westport Community Economic Development Corporation Margaret Rosch Jones Awards All Saints Episcopal Church Cool Green Schools Maryland Coastal Bays Program Sky Valley Association, Inc. -

Watersheds.Pdf

Watershed Code Watershed Name 02130705 Aberdeen Proving Ground 02140205 Anacostia River 02140502 Antietam Creek 02130102 Assawoman Bay 02130703 Atkisson Reservoir 02130101 Atlantic Ocean 02130604 Back Creek 02130901 Back River 02130903 Baltimore Harbor 02130207 Big Annemessex River 02130606 Big Elk Creek 02130803 Bird River 02130902 Bodkin Creek 02130602 Bohemia River 02140104 Breton Bay 02131108 Brighton Dam 02120205 Broad Creek 02130701 Bush River 02130704 Bynum Run 02140207 Cabin John Creek 05020204 Casselman River 02140305 Catoctin Creek 02130106 Chincoteague Bay 02130607 Christina River 02050301 Conewago Creek 02140504 Conococheague Creek 02120204 Conowingo Dam Susq R 02130507 Corsica River 05020203 Deep Creek Lake 02120202 Deer Creek 02130204 Dividing Creek 02140304 Double Pipe Creek 02130501 Eastern Bay 02141002 Evitts Creek 02140511 Fifteen Mile Creek 02130307 Fishing Bay 02130609 Furnace Bay 02141004 Georges Creek 02140107 Gilbert Swamp 02130801 Gunpowder River 02130905 Gwynns Falls 02130401 Honga River 02130103 Isle of Wight Bay 02130904 Jones Falls 02130511 Kent Island Bay 02130504 Kent Narrows 02120201 L Susquehanna River 02130506 Langford Creek 02130907 Liberty Reservoir 02140506 Licking Creek 02130402 Little Choptank 02140505 Little Conococheague 02130605 Little Elk Creek 02130804 Little Gunpowder Falls 02131105 Little Patuxent River 02140509 Little Tonoloway Creek 05020202 Little Youghiogheny R 02130805 Loch Raven Reservoir 02139998 Lower Chesapeake Bay 02130505 Lower Chester River 02130403 Lower Choptank 02130601 Lower -

American Eel: Collection and Relocation Conowingo Dam, Susquehanna River, Maryland 2016

American Eel: Collection and Relocation Conowingo Dam, Susquehanna River, Maryland 2016 Chris Reily, Biological Science Technician, MD Fish and Wildlife Conservation Office, USFWS Steve Minkkinen, Project Leader, MD Fish and Wildlife Conservation Office, USFWS 1 BACKGROUND The American Eel (Anguilla rostrata) is the only species of freshwater eel in North America and originates from the Sargasso Sea in the North Atlantic Ocean (USFWS 2011). The eels are catadromous, hatching in saltwater and maturing in freshwater before returning to their natal waters to spawn. Larval eels (referred to as leptocephalus larvae) are transported throughout the eastern seaboard via ocean currents where their range extends from Brazil to Greenland. By the time the year-long journey to the coast is over, they have matured into the “glass eel” phase and have developed fins and taken on the overall shape of the adults (Hedgepath 1983). After swimming upstream into continental waters, the 5-8 cm glass eels mature into “elvers” at which time they take on a green-brown to gray pigmentation and grow beyond 10 cm in length (Haro and Krueger 1988). Elvers migrate upstream into estuarine and riverine environments where they will remain as they change into sexually immature “yellow eels”. Yellow eels have a yellow-green to olive coloration and will typically remain in this stage for three to 20 years before reaching the final stage of maturity. The eels may begin reaching sexual maturity when they reach at least 25 cm in length and are called “silver eels”. Silver eels become darker on the dorsal side and silvery or white on the ventral side and continue to grow as they complete their sexual maturation. -

Jonesfallsexecsummary.Pdf

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY BACKGROUND The Jones Falls watershed is located in west-central Baltimore County and the City of Baltimore (see Figure E-1). The drainage features of the watershed are dominated by Jones Falls which discharges to Lake Roland. The stream resumes flow at the base of the reservoir for approximately 4,000 feet to the Baltimore City line between Interstate 83 and Route 25. From the City line, the stream flows in a generally south-southeasterly direction through the City until it discharges to the Patapsco River at the Northwest Harbor. This plan only addresses the Baltimore County portion of the watershed. The total watershed area in Baltimore County is approximately 26,000 acres or 40 square miles. The watershed generally extends from Reisterstown Road in the vicinity of Owings Mills to west; Greenspring Avenue to Broadway Road and Padonia Road to the north; Towson to the east; and the Baltimore City line to the south. For the purposes of this study the eight sub-watersheds were defined including the mainstem of Jones Falls above Lake Roland (Sub-watershed 1), North Branch (Sub-watershed 2), Dipping Pond Run (Sub- watershed 3), Deep Run (Sub-watershed 4), Roland Run (Sub-watershed 5), Towson Run (Sub-watershed 6), Lower Jones Falls (Sub-watershed 7) and Slaughterhouse/Moores Branch (Sub-watershed 8) (see Figure E-2). Historically, the Jones Falls watershed, as well as many other watersheds in the County, have been adversely impacted by land development, nonpoint source pollution, mining and agricultural activities. These impacts have included loss and degradation of natural habitat, stream channel erosion, and increased sediment, nutrient and other pollutant loads. -

Northeastern Jones Falls Small Watershed Action Plan Volume 2: Appendices D & E

Northeastern Jones Falls Small Watershed Action Plan Volume 2: Appendices D & E January 2013 December 2012 Final Prepared by: Baltimore County Department of Environmental Protection and Sustainability In Consultation with: Northeastern Jones Falls SWAP Steering Committee NORTHEASTERN JONES FALLS SMALL WATERSHED ACTION PLAN VOLUME II: APPENDICES D & E Appendix D Northeastern Jones Falls Characterization Report Appendix E Applicable Total Maximum Daily Loads APPENDIX D NORTHEASTERN JONES FALLS CHARACTERIZATION REPORT A-1 Northeastern Jones Falls Characterization Report Final December 2012 NORTHEASTERN JONES FALLS CHARACTERIZATION REPORT TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Purpose of the Characterization 1-1 1.2 Location and Scale of Analysis 1-1 1.3 Report Organization 1-5 CHAPTER 2 LANDSCAPE AND LAND USE 2.1 Introduction 2-1 2.2 The Natural Landscape 2-2 2.2.1 Climate 2-2 2.2.2 Physiographic Province and Topography 2-2 2.2.2.1 Location and Watershed Delineation 2-2 2.2.2.2 Topography 2-3 2.2.3 Geology 2-4 2.2.4 Soils 2-7 2.2.4.1 Hydrologic Soil Groups 2-7 2.2.4.2 Soil Erodibility 2-9 2.2.5 Forest 2-11 2.2.5.1 Forest Cover 2-11 2.2.6 Stream Systems 2-11 2.2.6.1 Stream System Characteristics 2-12 2.2.6.2 Stream Riparian Buffers 2-14 2.3 Human Modified Landscape 2-16 2.3.1 Land Use and Land Cover 2-16 2.3.2 Population 2-19 2.3.3 Impervious Surfaces 2-21 2.3.4 Drinking Water 2-24 2.3.4.1 Public Water Supply 2-24 2.3.5 Waste Water 2-24 2.3.5.1 Septic Systems 2-24 2.3.5.2 Public Sewer 2-24 2.3.5.3 Waste Water Treatment Facilities 2-26