Suffering and Trauma: Identity of Partition in the Movie Garam Hava

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Literary Herald

ISSN : 2454-3365 THE LITERARY HERALD AN INTERNATIONAL REFEREED ENGLISH E-JOURNAL A Quarterly Indexed Open-access Online JOURNAL Vol.1, No.1 (June 2015) Editor-in-Chief: Dr. Siddhartha Sharma Managing Editor: Dr. Sadhana Sharma www.TLHjournal.com [email protected] hhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkk;khngggh www.TLHjournal.com The Literary Herald ISSN: 2454-3365 An International Refereed English e-Journal The Representation of Agony during Partition as shown in M S Sathyu’s film “Garm Hawa” Ms Rekha Paresh Parmar Associate Professor Department of English Veer Narmad South Gujarat University, Surat Abstract “Garm Hawa” (Scorching Winds/Hot Winds) is a 1973 Hindi Urdu drama film directed by M S Sathyu with veteran actor Balraj Sahni as the lead. It was written by Kaifi Azmi and Shama Zaidi, based on an unpublished short story by a famous Urdu writer Ismat Chughtai. This controversial film has won several national awards in 1974 including a National Integration award. This political narrative deals with the plight of a North Indian Muslim businessman Salim Mirza and his family in 1947 in Agra. He is a patriot and a Muslim shoemaker, struggles to survive in this pathetic and critical condition of communal riots. He is in a dilemma either to live in India or to emigrate to Pakistan like his other family members. The Mirza family suffers for not doing anything wrong in this post-partition environment. They could neither manage their business nor got the job. The social and marital relations are affected. Salim Mirza’s elder son Baqar moves to Pakistan with his family. His daughter Amina is frustrated having two affairs with her cousins and committed suicide. -

Tujhe Suraj Kahu Ya Chanda Mp3

Tujhe suraj kahu ya chanda mp3 Continue {title:Tujhe Suraj Kahoon Ya Chanda,atw:https:\/\/a10.gaanacdn.com\/gn_img\/albums\/D0PKLqr3Gl\/0PKL66wWGl\/size_m.jpg,id:82969,path:{medium: [{message:f2zTFDPUfiwA8qO4ucPGy\/eN8ZpUu5+\/DM5DPvkHTGv6A+IadqV58tELClIK8O2BT+Xx9P7zZG9NjBVKtnP+XBa\/zKoF+GN9UgT9oSmNZwieIfulqkc2vNPMrn6d4Xd7ts7N5I9MJSg1E1FzIMJxRkYrmIjx\/pyJSIuL7VAVZ4OOEqieZgRLXb99cBK83q5meK13UtwT\/ULJ4U8dfdlJQgwOS0vNZYGCHsHS0ORbw+Yrhh92P1DwS5EpKamu0PxEHSmMGkxNQJYeTpdRQaPcy7mQhD6ckq\/0qiJzmYhHSp9Z5l1632K+aPHmKgrTqikEOqXmYTXl2xCpwo7EitlQPg==,bitRate:64,expiryTime:1603007435}],high: [{message:f2zTFDPUfiwA8qO4ucPGy\/eN8ZpUu5+\/DM5DPvkHTGv6A+IadqV58tELClIK8O2BuH9NOwJ2v036hVvfQpvXNt5dr+tiCs9OazTYxF5SMbn+02CAFVuHZqzpZ5XU64V9ttjX70Xi7htjbh2Q\/YSkzNR7hQwT8UaZibVaWvMYJk\/oiup5z0Dwy1+3m4gtF3VjqD50vBHFBwMRXrOPLMWhUuID4z\/YIRMjNh98goTXD9tlIEcSJTv\/W0\/MBRsxNggZflzt4phpB3mfGIS2xMnN2gW0sKcIhXdoGtU6sq8\/cbfExaG8Ocaq388lzR1SZgo0H7quxxchXYjKfgKWSytSE1Ef70AqWWreYZ+bN1abZu4=,bitRate:128,expiryTime:1603007435}],auto: [{message:f2zTFDPUfiwA8qO4ucPGy\/eN8ZpUu5+\/DM5DPvkHTGv6A+IadqV58tELClIK8O2BVJml5ycKXwsEY\/AwExlsTHdTdLDbfiylwrh1AgpL8AX8D494JIipnO8OZ4oGlTePjx4LzyZBTg9qgBuYk0B9lAp6Q+\/e+06gdnJWBD7wrno1T8jiQY5q0KJyyci8ThFEkvciX0crNtGIg7pyyecf0c3T+fCbInOmHV4v48vWL0Oy7VN+gTGgLGMXzwImuI5F6QTU1gh+vicFN62SyIOdIZo0P33mvpM8NNJEG0zIOpGJzEACIqc2dw0ILtnB3\/4vIX3R075GTfa\/svWwBZwIDQvX1a20hABMLw\/+poOSl5s4uVW1BwamJV3uM6dpFG46,bitRate:,expiryTime:1603007435}]},track_ids:82969,share_url:\/song\/tujhe- suraj-kahoon-ya-chanda,object_type:10,status:0,source:2,duration:268,source_id:25765, -

Best Dialogue

Kishore Kumar and Lata Mangeshkar still transport us to a different era! THE GLOBAL TIMES | MONDAY, JULY 30, 2012 Grandparents of Arpit Jain, V, AIS MV 7 Big Story Bollywood...then and now Pragati Priya, AIS Saket, XII Padukone a la Cocktail style could offer some ways than one. Indian film industry has come a long way since inspiration. Ours is a country where cinema is religion, some- then but this is just the beginning..picture abhi omething gone wrong? Never mind! After Bollywood weaves itself effortlessly into every thing that binds all of us together, a part of in- baaki hai mere dost. all, bade bade deshon me aisi choti choti aspect of our everyday lives; becoming an inte- credible India. In fact, Indians are known to eat, It is time to revisit those special and magical mo- Sbaatein hoti rehti hain. gral part of our very being. Indian cinema with its drink and sleep Bollywood. But the filmy obses- ments which have entertained us, accompanying Heading for a vacation. Why not? Zindagi Na colourful song and dance routines, robust dia- sion has been a long and gradual process. Many us in those dull moments over the years. So, grab Milegi Dobara. logues, dream sequences and gorgeous locales has moons ago, when India had only one channel, Do- some popcorn and get ready for your filmy A benevolent friend? Call her Mother India! been absorbed into our DNA from our childhood ordarshan, the Sunday evening movie used to be journey through the celluloid century. Wish to up your style quotient? Deepika and incorporated in our everyday lives in more the highlight of a typical week. -

Literary Herald ISSN: 2454-3365 UGC-Approved Journal an International Refereed English E-Journal Impact Factor: 2.24 (IIJIF)

www.TLHjournal.com Literary Herald ISSN: 2454-3365 UGC-Approved Journal An International Refereed English e-Journal Impact Factor: 2.24 (IIJIF) IPTA and National Identity: History, Theatre and a Culture of Touring Dr Samipendra Banerjee Assistant Professor Department of English University of Gour Banga Malda, West Bengal Abstract: Over the past decades there has been a growing interest in the historiography of Modern Indian Theatre. This paper is an attempt to focus on one of the most dynamic moments in the history of Modern Indian Theatre, the emergence of the Indian People‘s Theatre Association. The formation of IPTA in 1943 is an event of immense historical significance that needs greater critical inquiry. I attempt a review of the history of the IPTA with a focus on its theatre and show how the IPTA in its activist stance towards anti-colonial rule was also a key factor in imagining an emerging nation. IPTA‘s diverse theatrical oeuvre, including plays like Sambhu Mitra‘s Nabanna was instrumental in the construction of national identity. I also argue that despite its organizational decentralization, IPTA‘s role in the imagining of the nation became possible because of a crucial ploy of ‗touring‘, what I refer to as a ‗culture of touring‘. Keywords: IPTA, Modern Indian Theatre, historiography, National Identity, Nabanna, Culture of Touring. With the achievement of political independence in 1947 and the end of British rule, India stepped on to a phase of massive reconstruction of the nation. This was a project of asserting an identity, of simultaneous reconstruction and deconstruction, of decolonization and a rising postcolonial practice in various ways. -

Anil Biswas – Filmography Source: Hamraz’S Hindi Film Geet Kosh (Digitization: Ketan Dholakia, Vinayak Gore, and Balaji Murthy)

Anil Biswas – Filmography Source: Hamraz’s Hindi Film Geet Kosh (Digitization: Ketan Dholakia, Vinayak Gore, and Balaji Murthy) Contents Anil Biswas – Filmography ....................................................................................................................................... 1 1) Dharam Ki Devi ..................................................................................................................... 3 2) Fida-e-Vatan (alias Tasveer-e-vafa) ...................................................................................... 3 3) Piya Ki Jogan (alias Purchased Bride) ................................................................................... 3 4) Pratima (alias Prem Murti) ..................................................................................................... 4 5) Prem Bandhan (alias Victims of Love) .................................................................................. 4 6) Sangdil Samaj ......................................................................................................................... 4 7) Sher Ka Panja ......................................................................................................................... 5 8) Shokh Dilruba ......................................................................................................................... 5 9) Bulldog ................................................................................................................................... 5 10) Dukhiari (alias A Tale of Selfless Love) -

Globalizing Pakistani Identity Across the Border: the Politics of Crossover Stardom in the Hindi Film Industry

DePaul University Via Sapientiae College of Communication Master of Arts Theses College of Communication Winter 3-19-2018 Globalizing Pakistani Identity Across The Border: The Politics of Crossover Stardom in the Hindi Film Industry Dina Khdair DePaul University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/cmnt Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Khdair, Dina, "Globalizing Pakistani Identity Across The Border: The Politics of Crossover Stardom in the Hindi Film Industry" (2018). College of Communication Master of Arts Theses. 31. https://via.library.depaul.edu/cmnt/31 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Communication at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of Communication Master of Arts Theses by an authorized administrator of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GLOBALIZING PAKISTANI IDENTITY ACROSS THE BORDER: THE POLITICS OF CROSSOVER STARDOM IN THE HINDI FILM INDUSTRY INTRODUCTION In 2010, Pakistani musician and actor Ali Zafar noted how “films and music are one of the greatest tools of bringing in peace and harmony between India and Pakistan. As both countries share a common passion – films and music can bridge the difference between the two.”1 In a more recent interview from May 2016, Zafar reflects on the unprecedented success of his career in India, celebrating his work in cinema as groundbreaking and forecasting a bright future for Indo-Pak collaborations in entertainment and culture.2 His optimism is signaled by a wish to reach an even larger global fan base, as he mentions his dream of working in Hollywood and joining other Indian émigré stars like Priyanka Chopra. -

How Rural Is Hindi Cinema? 14 Shoma A

MORPARIA’S PAGE E-mail: [email protected] Contents AUGUST 2016 VOL.20/1 ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ THEME: Morparia’s page 2 Rural India The ‘country’ calls… 5 Nivedita Louis An irreparable loss 6 Managing Editor Bharat Dogra Mrs. Sucharita R. Hegde The urban farmers 8 Hiren Kumar Bose Editor A project called Mandya 2020 11 Anuradha Dhareshwar E. Vijayalakshmi Rajan How rural is Hindi cinema? 14 Shoma A. Chatterji Assistant Editor Decentralise now! 16 E.Vijayalakshmi Rajan 6 Prof. G. Palanithurai Not charged! 19 Design Samarth Bansal H. V. Shiv Shankar Subsidies that hurt 21 Bharat Dogra Marketing Know India Better Mahesh Kanojia Haridwar: 23 The holy time warp Gustasp & Jeroo Irani OIOP Clubs Co-ordinator Face to Face 35 Vaibhav Palkar Jaya Jaitly : Anuradha Dhareshwar Features Subscription In-Charge Renewable, but is it sustainable? 39 Nagesh Bangera G. Venkatesh Our bulwark 41 23 Lt. Gen. Vijay Oberoi Advisory Board Through the bars of hope 44 Sucharita Hegde Sujit Bhar Justice S. Radhakrishnan Smile...it enhances your face value! 46 Venkat R. Chary A. Radhakrishnan An unseemly battle 48 Prof. Avinash Kolhe Printed & Published by The lips that bragged, the feet that danced 50 Mrs. Sucharita R. Hegde for A. Radhakrishnan One India One People Foundation, Column 52 Mahalaxmi Chambers, 4th floor, Nature watch : Bittu Sahgal 22, Bhulabhai Desai Road, Infocus : C.V. Aravind Mumbai - 400 026 Jaya Jaitly Young India 54 Tel: 022-2353 4400 35 Great Indians 56 Fax: 022-2351 7544 e-mail: [email protected] [email protected] Printed at: Graphtone (India) Pvt. Ltd. A1 /319, Shah & Nahar Industrial Estate. -

Downloads/NZJAS-%20Dec07/02Booth6.Pdfarameters.Html

Ph.D. Thesis ( FEMALE PROTAGONIST IN HINDI CINEMA: Women’s Studies A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF REPRESENTATIVE FILMS FROM 1950 TO 2000 ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF ) Doctor of Philosophy IN WOMEN’S STUDIES SIFWAT MOINI BY SIFWAT MOINI UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF DR. PITABAS PRADHAN (Associate Professor) 201 6 ADVANCED CENTRE FOR WOMEN’S STUDIES ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH-202002 (INDIA) 2016 DEPARTMENT OF MASS COMMUNICATION ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY Dr. Pitabas Pradhan Associate Professor Certificate This is to certify that Ms. Sifwat Moini has completed her Ph.D. thesis entitled ‘Female Protagonist in Hindi Cinema: A Comparative Study of Representative Films from 1950 to 2000’ under my supervision. This thesis has been submitted to the Advanced Centre for Women’s Studies, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh for the award of degree of Doctor of Philosophy. It is further certified that this thesis represents original work and to the best of my knowledge has not been submitted for any degree of this university or any other university. (Dr. Pitabas Pradhan) Supervisor Sarfaraz House, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh-202002 Phone: 0571-2704857, Ext.: 1355,Email: [email protected], [email protected] ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I owe all of my thankfulness to the existence of the Almighty and the entities in which His munificence is reflected for the completion of this work. My heartfelt thankfulness is for my supervisor, Dr. Pitabas Pradhan. His presence is a reason of encouragement, inspiration, learning and discipline. His continuous support, invaluable feedback and positive criticism made me sail through. I sincerely thank Prof. -

Waqt 1965 Songs Download

Waqt 1965 songs download Waqt () free mp3 songs download,old hindi songs,sunil dutt. Direct Download Links For Hindi Movie Waqt MP3 Songs. Download Waqt () Songs Indian Movies Hindi Mp3 Songs, Waqt () Mp3 Songs Zip file. Free High quality Mp3 Songs Download Kbps. Aage Bhi Jaane Na 3. Singer: Asha Bhosle mb | Hits. File. Meri Zohra 3. Singer: Manna Dey mb | Hits. File. 3. Waqt movie Mp3 Songs Download. Waqt Se Din Aur Raat (Waqt), Aage Bhi Jaane Na Tu (Waqt), Hum Jab Simat Ke Aapki (Waqt), Aye Meri Zohra Zati. Download Waqt Array Full Mp3 Songs By Asha Bhosle Movie - Album Released On 26 Feb, in Category Hindi - Mr-Jatt. Star Cast: Balraj Sahni, Sunil Dutt, Sadhana, Raaj Kumar, Shashi Kapoor, Sharmila Tagore, Rehman, Manmohan Krishna Director: Yash Chopra Music: Ravi. Listen and download old hindi songs of Waqt () Mp3 Songs - Aage Bhi Jaane Na Tu, Aye Meri Zohra Jabeen, Chehre Pe Khushi Chha Jati. Waqt Songspk, Download Waqt Mp3 Songs, Waqt Music Kbps Free Bollywood Hindi Sountracks. Tags: Waqt () Download, Waqt () Free Download, Waqt () Kbps Song Free Download, Waqt () kbps Mp3 Songs Free Download. Download Waqt () Hindi Mp3 Songs Waqt () Tracklist 'n' Download Links:. Click below to Download all the songs RS or SS or MF OR Click on. Download Download songs of waqt from songs pk. songs. pk Album: Waqt -. songs. pk Lead performer: Waqt Se Din Aur Raat -. songs. pk. DOWNLOAD Tags: Download Waqt Songs Mp3 Songs, hindi movie Mp3 Songs of Waqt Songs download, download bollywood. 01 - Waqt Se Din Aur Raat (Waqt ) Size: MB. -

Contemporary Cinema & Indian Nationalism

Contemporary Cinema & Indian Nationalism History 175C: Special Topics in Indian History UCLA: Spring 2018 Tuesdays & Thursdays 2-3:15 PM, in Public Affairs 1222 Vinay Lal Department of History, UCLA Office: Bunche Hall 5240 Office Hours: Tuesdays & Thursdays, 3:30-4:30 PM, and by appointment Tel: 310.825.8276; Department Office (Bunche 6265): 310.825.4601 email: [email protected] Instructor’s website: southasia.ucla.edu Instructor’s webpages on cinema: http://southasia.ucla.edu/culture/cinema/ Course website: https://moodle2.sscnet.ucla.edu/course/view/18S-HIST175C-1 YouTube page: youtube.com/user/dillichalo Blog: https://vinaylal.wordpress.com This upper-division lecture course, offered for the first time, takes up the twin stories of Indian cinema and nationalism in the colonial and postcolonial period, and suggests that the intersection of history and cinema might have some unusual insights to offer about the nature of nationalist narratives. In broader terms, this lecture course also furnishes an introduction to the culture and history of modern Hindi-language cinema, the study of modern Indian history, some of the broader theoretical literature on nationalism and patriotism, and the study of popular culture. The use of films and visual material in the study of history has become increasingly popular over the course of the last three decades; however, this course does not view cinema merely an as instrument for the study of Indian history. Popular cinema, this lecture presumes, is an intrinsically interesting subject of inquiry, even if Indian scholars have come to this realization long after the Indian public had already declared its unmitigated affection for the movies. -

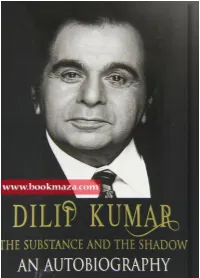

Dilip-Kumar-The-Substance-And-The

No book on Hindi cinema has ever been as keenly anticipated as this one …. With many a delightful nugget, The Substance and the Shadow presents a wide-ranging narrative across of plenty of ground … is a gold mine of information. – Saibal Chatterjee, Tehelka The voice that comes through in this intriguingly titled autobiography is measured, evidently calibrated and impossibly calm… – Madhu Jain, India Today Candid and politically correct in equal measure … – Mint, New Delhi An outstanding book on Dilip and his films … – Free Press Journal, Mumbai Hay House Publishers (India) Pvt. Ltd. Muskaan Complex, Plot No.3, B-2 Vasant Kunj, New Delhi-110 070, India Hay House Inc., PO Box 5100, Carlsbad, CA 92018-5100, USA Hay House UK, Ltd., Astley House, 33 Notting Hill Gate, London W11 3JQ, UK Hay House Australia Pty Ltd., 18/36 Ralph St., Alexandria NSW 2015, Australia Hay House SA (Pty) Ltd., PO Box 990, Witkoppen 2068, South Africa Hay House Publishing, Ltd., 17/F, One Hysan Ave., Causeway Bay, Hong Kong Raincoast, 9050 Shaughnessy St., Vancouver, BC V6P 6E5, Canada Email: [email protected] www.hayhouse.co.in Copyright © Dilip Kumar 2014 First reprint 2014 Second reprint 2014 The moral right of the author has been asserted. The views and opinions expressed in this book are the author’s own and the facts are as reported by him, which have been verified to the extent possible, and the publishers are not in any way liable for the same. All photographs used are from the author’s personal collection. All rights reserved. -

Bollywood Songs: Re Ection of Wounded Nation in the Post-Independence

SHANLAX International Journal of English Bollywood Songs: Re ection of Wounded Nation in the Post-Independence Avish Setia OPEN ACCESS Research Scholar, Department of English and Cultural Studies Panjab University, Chandigarh Volume : 6 Abstract Issue : 3 The present paper examines how the Bombay-based Hindi lm cinema culturally obliges to respond to the national crisis in the post-independence era. The paper will deal with Bollywood lyrics in general and how they highlight the crisis of the nation one after the other, for instance, Month : June brutal partition, Indo-China War, Indo-Pak War, White-Revolution, and Green-Revolution. Along with, the brief discussion will be on the lampooned religious identities and religious Year: 2018 tensions shown in Bollywood songs in the aftermath of partition of India/Pakistan. Songs were often based on communal harmony, and the paper will brie y examine how the Muslim characters were shown sane and sensible in the Bollywood lms. The project analyzes Hindi ISSN: 2320-2645 lm lyrics through the compilations of Harmandir Singh Hamraz’s Hindi Film Geet-Kosh and Mir, Ali Husain., and Raza Mir’s Anthems of Resistance: A Celebration of Progressive Urdu Poetry (as primary texts). The project undertakes the study of various other articles and books Received: related to the area of research. The paper will conclude by discussing the emergence of White- 30.03.2018 Revolution and Green-Revolution during the 1960s. Keywords: Partition, Religion, Indo-China War, Indo-Pak War, White-Revolution, Green- Revolution. Accepted: 14.06.2018 Introduction Published: Bollywood songs were introduced in the movies ever since the advent 26.06.2018 of the Hindi lm cinema.