The Earliest Drawings of Datable Auroras and a Two-Tail Comet from the Syriac Chronicle of Zūqnīn

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Applying Satellite Data Sources in the Documentation and Landscape Modelling for Graeco-Roman/Byzantine Fortified Sites in the Tūr Abdin Area, Eastern Turkey

ISPRS Annals of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, Volume IV-2/W2, 2017 26th International CIPA Symposium 2017, 28 August–01 September 2017, Ottawa, Canada APPLYING SATELLITE DATA SOURCES IN THE DOCUMENTATION AND LANDSCAPE MODELLING FOR GRAECO-ROMAN/BYZANTINE FORTIFIED SITES IN THE TŪR ABDIN AREA, EASTERN TURKEY Kenneth Silvera *, Minna Silverb, Markus Törmä c, Jari Okkonend, Tuula Okkonene a Principal Investigator, Dr., The Institute for Digital Archaeology, Oxford, UK, [email protected] bAdj. Prof., Oulu University, Finland, [email protected], c Techn. Lic., Aalto University, Finland, [email protected] d Dr. Oulu University, Finland, [email protected] , e Dr. Oulu University, Finland, [email protected] Commission II KEY WORDS: Remote sensing, satellite images, GeoEye-1, Roman limes studies, Byzantine studies, archaeological survey, GIS ABSTRACT: In 2015-2016 the Finnish-Swedish Archaeological Project in Mesopotamia (FSAPM) initiated a pilot study of an unexplored area in the Tūr Abdin region in Northern Mesopotamia (present-day Mardin Province in southeastern Turkey). FSAPM is reliant on satellite image data sources for prospecting, identifying, recording, and mapping largely unknown archaeological sites as well as studying their landscapes in the region. The purpose is to record and document sites in this endangered area for saving its cultural heritage. The sites in question consist of fortified architectural remains in an ancient border zone between the Graeco-Roman/Byzantine world and Parthia/Persia. The location of the archaeological sites in the terrain and the visible archaeological remains, as well as their dimensions and sizes were determined from the ortorectified satellite images, which also provided coordinates. -

KIA Bulletin -Session 34.Pdf

Contributions Arithmetic His major contributions to mathematics, Khwarizmi’s second major work was on the astronomy, astrology, geography and cartography subject of arithmetic, which survived in a Latin provided foundations for later and even more translation but was lost in the original Arabic. widespread innovation in algebra, trigonometry, and his other areas of interest. His systematic and Geography logical approach to solving linear and quadratic Khwarizmi’s third major work is his Kitab surat equations gave shape to the discipline of algebra, al-Ard «Book on the appearance of the Earth». It a word that is derived from the name of his book is a revised and completed version of Ptolemy’s on the subject. «The Compendious Book on Geography, consisting of a list of 2402 coordinates Calculation by Completion and Balancing». The of cities and other geographical features following book was first translated into Latin in the twelfth a general introduction. century. His book on the Calculation with Hindu Numerals, Astronomy was principally responsible for the diffusion of Khwarizmi’s Zij al-sindhind (astronomical tables) the Indian system of numeration in the Middle- is a work consisting of approximately 37 chapters East and then Europe. This book also translated on calendrical and astronomical calculations and into Latin in the twelfth century, as Algoritmi de 116 tables with calendrical, astronomical and numero Indorum. From the name of the author, astrological data, as well as a table of sine values. rendered in Latin as algoritmi, originated the term This is one of many Arabic zijes based on the Indian algorithm. Khwarizmi systematized and corrected astronomical methods known as the sindhind. -

The Natural Science Underlying Big History

Review Article [Accepted for publication: The Scientific World Journal, v2014, 41 pages, article ID 384912; printed in June 2014 http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2014/384912] The Natural Science Underlying Big History Eric J. Chaisson Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138 USA [email protected] Abstract Nature’s many varied complex systems—including galaxies, stars, planets, life, and society—are islands of order within the increasingly disordered Universe. All organized systems are subject to physical, biological or cultural evolution, which together comprise the grander interdisciplinary subject of cosmic evolution. A wealth of observational data supports the hypothesis that increasingly complex systems evolve unceasingly, uncaringly, and unpredictably from big bang to humankind. This is global history greatly extended, big history with a scientific basis, and natural history broadly portrayed across ~14 billion years of time. Human beings and our cultural inventions are not special, unique, or apart from Nature; rather, we are an integral part of a universal evolutionary process connecting all such complex systems throughout space and time. Such evolution writ large has significant potential to unify the natural sciences into a holistic understanding of who we are and whence we came. No new science (beyond frontier, non-equilibrium thermodynamics) is needed to describe cosmic evolution’s major milestones at a deep and empirical level. Quantitative models and experimental tests imply that a remarkable simplicity underlies the emergence and growth of complexity for a wide spectrum of known and diverse systems. Energy is a principal facilitator of the rising complexity of ordered systems within the expanding Universe; energy flows are as central to life and society as they are to stars and galaxies. -

OLBA XXIII (Ayrıbasım / Offprint)

ISSN 1301 7667 MERSİN ÜNİVERSİTESİ KILIKIA ARKEOLOJİSİNİ ARAŞTIRMA MERKEZİ MERSIN UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF THE RESEARCH CENTER OF CILICIAN ARCHAEOLOGY KAAM YAYINLARI OLBA XXIII (Ayrıbasım / Offprint) MERSİN 2015 KAAM YAYINLARI OLBA XXIII © 2015 Mersin Üniversitesi/Türkiye ISSN 1301 7667 Yayıncı Sertifika No: 14641 OLBA dergisi; ARTS & HUMANITIES CITATION INDEX, EBSCO, PROQUEST ve TÜBİTAK-ULAKBİM Sosyal Bilimler Veri Tabanlarında taranmaktadır. Alman Arkeoloji Enstitüsü’nün (DAI) Kısaltmalar Dizini’nde ‘OLBA’ şeklinde yer almaktadır. OLBA dergsi hakemlidir. Makalelerdeki görüş, düşünce ve bilimsel değerlendirmelerin yasal sorumluluğu yazarlara aittir. The articles are evaluated by referees. The legal responsibility of the ideas, opinions and scientific evaluations are carried by the author. OLBA dergisi, Mayıs ayında olmak üzere, yılda bir kez basılmaktadır. Published each year in May. KAAM’ın izni olmadan OLBA’nın hiçbir bölümü kopya edilemez. Alıntı yapılması durumunda dipnot ile referans gösterilmelidir. It is not allowed to copy any section of OLBA without the permit of KAAM. OLBA dergisinde makalesi yayımlanan her yazar, makalesinin baskı olarak ve elektronik ortamda yayımlanmasını kabul etmiş ve telif haklarını OLBA dergisine devretmiş sayılır. Each author whose article is published in OLBA shall be considered to have accepted the article to be published in print version and electronically and thus have transferred the copyrights to the journal OLBA.. OLBA’ya gönderilen makaleler aşağıdaki web adresinde ve bu cildin giriş sayfalarında belirtilen formatlara uygun olduğu taktirde basılacaktır. Articles should be written according the formats mentioned in the following web address. Redaktion: Yrd. Doç. Dr. Deniz Kaplan OLBA’nın yeni sayılarında yayınlanması istenen makaleler için yazışma adresi: Correspondance addresses for sending articles to following volumes of OLBA: Prof. -

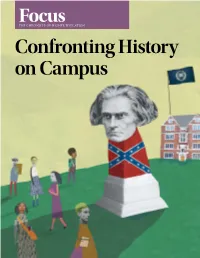

Confronting History on Campus

CHRONICLEFocusFocus THE CHRONICLE OF HIGHER EDUCATION Confronting History on Campus As a Chronicle of Higher Education individual subscriber, you receive premium, unrestricted access to the entire Chronicle Focus collection. Curated by our newsroom, these booklets compile the most popular and relevant higher-education news to provide you with in-depth looks at topics affecting campuses today. The Chronicle Focus collection explores student alcohol abuse, racial tension on campuses, and other emerging trends that have a significant impact on higher education. ©2016 by The Chronicle of Higher Education Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, forwarded (even for internal use), hosted online, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. For bulk orders or special requests, contact The Chronicle at [email protected] ©2016 THE CHRONICLE OF HIGHER EDUCATION INC. TABLE OF CONTENTS OODROW WILSON at Princeton, John Calhoun at Yale, Jefferson Davis at the University of Texas at Austin: Students, campus officials, and historians are all asking the question, What’sW in a name? And what is a university’s responsibil- ity when the name on a statue, building, or program on campus is a painful reminder of harm to a specific racial group? Universities have been grappling anew with those questions, and trying different approaches to resolve them. Colleges Struggle Over Context for Confederate Symbols 4 The University of Mississippi adds a plaque to a soldier’s statue to explain its place there. -

ROUTES and COMMUNICATIONS in LATE ROMAN and BYZANTINE ANATOLIA (Ca

ROUTES AND COMMUNICATIONS IN LATE ROMAN AND BYZANTINE ANATOLIA (ca. 4TH-9TH CENTURIES A.D.) A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY TÜLİN KAYA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THE DEPARTMENT OF SETTLEMENT ARCHAEOLOGY JULY 2020 Approval of the Graduate School of Social Sciences Prof. Dr. Yaşar KONDAKÇI Director I certify that this thesis satisfies all the requirements as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Prof. Dr. D. Burcu ERCİYAS Head of Department This is to certify that we have read this thesis and that in our opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Assoc. Prof. Dr. Lale ÖZGENEL Supervisor Examining Committee Members Prof. Dr. Suna GÜVEN (METU, ARCH) Assoc. Prof. Dr. Lale ÖZGENEL (METU, ARCH) Assoc. Prof. Dr. Ufuk SERİN (METU, ARCH) Assoc. Prof. Dr. Ayşe F. EROL (Hacı Bayram Veli Uni., Arkeoloji) Assist. Prof. Dr. Emine SÖKMEN (Hitit Uni., Arkeoloji) I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Last name : Tülin Kaya Signature : iii ABSTRACT ROUTES AND COMMUNICATIONS IN LATE ROMAN AND BYZANTINE ANATOLIA (ca. 4TH-9TH CENTURIES A.D.) Kaya, Tülin Ph.D., Department of Settlement Archaeology Supervisor : Assoc. Prof. Dr. -

The Expansion of Christianity: a Gazetteer of Its First Three Centuries

THE EXPANSION OF CHRISTIANITY SUPPLEMENTS TO VIGILIAE CHRISTIANAE Formerly Philosophia Patrum TEXTS AND STUDIES OF EARLY CHRISTIAN LIFE AND LANGUAGE EDITORS J. DEN BOEFT — J. VAN OORT — W.L. PETERSEN D.T. RUNIA — C. SCHOLTEN — J.C.M. VAN WINDEN VOLUME LXIX THE EXPANSION OF CHRISTIANITY A GAZETTEER OF ITS FIRST THREE CENTURIES BY RODERIC L. MULLEN BRILL LEIDEN • BOSTON 2004 This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Mullen, Roderic L. The expansion of Christianity : a gazetteer of its first three centuries / Roderic L. Mullen. p. cm. — (Supplements to Vigiliae Christianae, ISSN 0920-623X ; v. 69) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 90-04-13135-3 (alk. paper) 1. Church history—Primitive and early church, ca. 30-600. I. Title. II. Series. BR165.M96 2003 270.1—dc22 2003065171 ISSN 0920-623X ISBN 90 04 13135 3 © Copyright 2004 by Koninklijke Brill nv, Leiden, The Netherlands All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Brill provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910 Danvers, MA 01923, USA. Fees are subject to change. printed in the netherlands For Anya This page intentionally left blank CONTENTS Preface ........................................................................................ ix Introduction ................................................................................ 1 PART ONE CHRISTIAN COMMUNITIES IN ASIA BEFORE 325 C.E. Palestine ..................................................................................... -

The Syrian Orthodox Church and Its Ancient Aramaic Heritage, I-Iii (Rome, 2001)

Hugoye: Journal of Syriac Studies 5:1, 63-112 © 2002 by Beth Mardutho: The Syriac Institute SOME BASIC ANNOTATION TO THE HIDDEN PEARL: THE SYRIAN ORTHODOX CHURCH AND ITS ANCIENT ARAMAIC HERITAGE, I-III (ROME, 2001) SEBASTIAN P. BROCK UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD [1] The three volumes, entitled The Hidden Pearl. The Syrian Orthodox Church and its Ancient Aramaic Heritage, published by TransWorld Film Italia in 2001, were commisioned to accompany three documentaries. The connecting thread throughout the three millennia that are covered is the Aramaic language with its various dialects, though the emphasis is always on the users of the language, rather than the language itself. Since the documentaries were commissioned by the Syrian Orthodox community, part of the third volume focuses on developments specific to them, but elsewhere the aim has been to be inclusive, not only of the other Syriac Churches, but also of other communities using Aramaic, both in the past and, to some extent at least, in the present. [2] The volumes were written with a non-specialist audience in mind and so there are no footnotes; since, however, some of the inscriptions and manuscripts etc. which are referred to may not always be readily identifiable to scholars, the opportunity has been taken to benefit from the hospitality of Hugoye in order to provide some basic annotation, in addition to the section “For Further Reading” at the end of each volume. Needless to say, in providing this annotation no attempt has been made to provide a proper 63 64 Sebastian P. Brock bibliography to all the different topics covered; rather, the aim is simply to provide specific references for some of the more obscure items. -

Acknowledgements

acknowledgements this book was the product of a British Acade my Mid- career Fellowship that I held 2018–19 at Aga Khan University, Institute for the Study of Muslim Ci- vilisations. I would like to thank every one at the Institute, especially the dean, Leif Stenberg, for their convivial support. My thinking on Dionysius of Tel- Mahre was first stimulated by a work- shop on elites in the caliphate that was or ga nized by Stefan Heidemann and Hannah Hagemann at Hamburg for the ERC proj ect ‘The Early Islamic Em- pire at Work’. Here I presented an early version of what became chapter 3 of this book, and the discussions I had there were very impor tant for thinking through my ideas. I also benefited from my involvement with Petra Sijpesteijn’s Leiden ERC proj ect, ‘Embedding Conquest: Naturalising Muslim Rule in the Early Islamic Empire (600–1000)’, where I presented an early version of chapter 4. Audi- ences at Oxford, Cambridge, London, Frankfurt and Milan provided feedback on many aspects of the work. Peter Van Nuffelen, Maria Conterno and Marianna Mazzola kindly shared with me their work on the fragments of Dionysius and I am very grateful to them indeed. I should like to show my par tic u lar thanks to Hannah Hagemann and Phil Booth, who read the entire manuscript of the book and made many valuable suggestions. I would also like to thank Averil Cameron, Andrew Marsham, Liza Anderson, Chip Coakley, David Taylor, Salam Rassi, Ed Hayes, Ed Zychowicz- Coghill, Fanny Bessard, Jan van Ginkel, Srecko Koralija, Daniel Hadas, James Montgomery, Andy Hilkens, Peter Sarris, Jack Tannous, Ben Tate, Sara Lerner, Hanna Siurua, Greg Fisher, and the anonymous reviewer from Prince ton University Press. -

Deep Space Chronicle Deep Space Chronicle: a Chronology of Deep Space and Planetary Probes, 1958–2000 | Asifa

dsc_cover (Converted)-1 8/6/02 10:33 AM Page 1 Deep Space Chronicle Deep Space Chronicle: A Chronology ofDeep Space and Planetary Probes, 1958–2000 |Asif A.Siddiqi National Aeronautics and Space Administration NASA SP-2002-4524 A Chronology of Deep Space and Planetary Probes 1958–2000 Asif A. Siddiqi NASA SP-2002-4524 Monographs in Aerospace History Number 24 dsc_cover (Converted)-1 8/6/02 10:33 AM Page 2 Cover photo: A montage of planetary images taken by Mariner 10, the Mars Global Surveyor Orbiter, Voyager 1, and Voyager 2, all managed by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. Included (from top to bottom) are images of Mercury, Venus, Earth (and Moon), Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune. The inner planets (Mercury, Venus, Earth and its Moon, and Mars) and the outer planets (Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune) are roughly to scale to each other. NASA SP-2002-4524 Deep Space Chronicle A Chronology of Deep Space and Planetary Probes 1958–2000 ASIF A. SIDDIQI Monographs in Aerospace History Number 24 June 2002 National Aeronautics and Space Administration Office of External Relations NASA History Office Washington, DC 20546-0001 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Siddiqi, Asif A., 1966 Deep space chronicle: a chronology of deep space and planetary probes, 1958-2000 / by Asif A. Siddiqi. p.cm. – (Monographs in aerospace history; no. 24) (NASA SP; 2002-4524) Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Space flight—History—20th century. I. Title. II. Series. III. NASA SP; 4524 TL 790.S53 2002 629.4’1’0904—dc21 2001044012 Table of Contents Foreword by Roger D. -

Menander Protector, Fragments 6.1-3

Menander Protector, Fragments 6.1-3 Sasanika Sources History of Menander the Guardsman (Menander Protector) was written at the end of the sixth century CE by a minor official of the Roman/Byzantine court. The original text is in Greek, but has survived only in a fragmentary form, quoted in compilations and other historical writings. The author, Menander, was a native of Constantinople, seemingly from a lowly class and initially himself not worthy of note. In a significant introductory passage, he courageously admits to having undertaken the writing of his History (’ st a) as a way of becoming more respectable and forging himself a career. He certainly was a contemporary and probably an acquaintance of the historian Theophylact Simocatta and worked within the same court of Emperor Maurice. His title of “Protector” seems to suggest a military position, but most scholars suspect that this was only an honorary title without any real responsibilities. Menander’s history claims to continue the work of Agathias and so starts from the date that Agathias left off, namely AD 557. His style of presentation, if not his actual writing style, are thus influenced by Agathias, although he seems much less partial than the former in presentation of the events. He seems to have had access to imperial archives and reports and consequently presents us with a seemingly accurate version of the events, although at time he might be exaggerating some of his facts. The following is R. C. Blockley’s English translation of the fragments 6.1-3 of Menander Protector’s History, which deals directly with the Sasanian-Roman peace treaty of 562 and provides us with much information about the details of negotiations that took place around this treaty. -

Can Literary Studies Survive? ENDGAME

THE CHRONICLE REVIEW CHRONICLE THE Can literary survive? studies Endgame THE CHRONICLE REVIEW ENDGAME CHRONICLE.COM THE CHRONICLE REVIEW Endgame The academic study of literature is no longer on the verge of field collapse. It’s in the midst of it. Preliminary data suggest that hiring is at an all-time low. Entire subfields (modernism, Victorian poetry) have essentially ceased to exist. In some years, top-tier departments are failing to place a single student in a tenure-track job. Aspirants to the field have almost no professorial prospects; practitioners, especially those who advise graduate students, must face the uneasy possibility that their professional function has evaporated. Befuddled and without purpose, they are, as one professor put it recently, like the Last Di- nosaur described in an Italo Calvino story: “The world had changed: I couldn’t recognize the mountain any more, or the rivers, or the trees.” At the Chronicle Review, members of the profession have been busy taking the measure of its demise – with pathos, with anger, with theory, and with love. We’ve supplemented this year’s collection with Chronicle news and advice reports on the state of hiring in endgame. Altogether, these essays and articles offer a comprehensive picture of an unfolding catastrophe. My University is Dying How the Jobs Crisis Has 4 By Sheila Liming 29 Transformed Faculty Hiring By Jonathan Kramnick Columbia Had Little Success 6 Placing English PhDs The Way We Hire Now By Emma Pettit 32 By Jonathan Kramnick Want to Know Where Enough With the Crisis Talk! PhDs in English Programs By Lisi Schoenbach 9 Get Jobs? 35 By Audrey Williams June The Humanities’ 38 Fear of Judgment Anatomy of a Polite Revolt By Michael Clune By Leonard Cassuto 13 Who Decides What’s Good Farting and Vomiting Through 42 and Bad in the Humanities?” 17 the New Campus Novel By Kevin Dettmar By Kristina Quynn and G.