NATUROPATHY and HOLISTIC MEDICINE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Review Article

REVIEW ARTICLE NATUROPATHY SYSTEM – A COMPLIMENTARY AND ALTERNATIVE AID IN DENTISTRY – A REVIEW Yatish Kumar Sanadhya1, Sanadhya Sudhanshu2, Sorabh R Jain3, Nidhi Sharma4 HOW TO CITE THIS ARTICLE: Yatish Kumar Sanadhya, Sanadhya Sudhanshu, Sorabh R Jain, Nidhi Sharma. “Naturopathy system – a complimentary and alternative aid in dentistry – a review”. Journal of Evolution of Medical and Dental Sciences 2013; Vol2, Issue 37, September 16; Page: 7077-7083. ABSTRACT: Coined by Dr. John Scheel, Henry Lindlahr crediting him as “father of Naturopathy”, Naturopathy system of Medicine is a system of healing science stimulating the body’s inherent power to regain health with the help of five great elements of nature. Naturopathy provides not only a simple practical approach to the management of disease, but a firm theoretical basic which is applicable to all holistic medical care and by giving attention to the foundations of health; also offers a more economical frame work for the medicine of future generation. Naturopathy is an approach to healing using “natural” means such as diet and lifestyle. For treatment, it primarily stresses on correcting all the factors involved and allowing the body to recover itself. In dentistry, various modalities are available therefore, supporting dental treatment. For the same purpose, this paper is intended to have an overview of other dental treatment modalities available via i.e. Naturotherapy. KEYWORDS: Nature therapy, hydrotherapy, therapeutics. INTRODUCTION: Naturopathy system of Medicine is a system of healing science stimulating the body’s inherent power to regain health with the help of five great elements of nature- Earth, Water, Air, Fire and Ether. -

Benefits of Yoga and Naturopathy in Human Life Dr

www.ijcrt.org © 2014 IJCRT | Volume 2, Issue 1 February 2014 | ISSN: 2320-2882 Benefits of Yoga and Naturopathy in Human Life Dr. RAZIA. K. I. Director (I/C) Department of Physical Education University of Kerala, Trivandrum- 695033 Abstract In Yoga and Naturopathy, meditation and different natural therapies are an integral aspect. With changing life style and global scenario, there have been changes in almost all the stream of traditional science to suit contemporary requirements. Various health clubs and training centers were opened up to help people get training and therapies comfortably. Now people do not have to really go into ashrams and forests to meditate. Traditional system like Naturopathy has also evolved from its traditional model. Nowadays, all kinds of electronic equipments are provided in these health clubs and training centers for physical exercises are prescribed by yoga. Naturopathic treatment also uses modern scientific machines to provide natural therapies. Individuals generally own these health clubs and training centers. They are registered under the Society's Act in jurisdiction of different states; no central regulations are there for these private institutes. These institutes are many in number and as such, no federal record is maintained. This is one of the most upcoming sectors. Many private training institutes also give training in yoga as free services, but most of them charge for their services. Their services are more popular in metropolitans and cities where people face problems like depression, stress, asthma, etc. due to pollution and conditions prevailing in cities. Multiple studies have confirmed the many mental and physical benefits of yoga. -

Bela Knjiga SNZ: Naturopatski Filozofski Nauk, Načela in Teorije

Bela knjiga SNZ: Naturopatski filozofski nauk, načela in teorije Zahvala Svetovna naturopatska zveza (SNF) se za sodelovanje pri posredovanju podatkov za izdelavo Bele knjige SNZ - naturopatski filozofski nauk, načela in teorije iskreno zahvaljuje naslednjim naturopatskim izobraževalnim ustanovam: Bastyr University, Združene države Amerike, Canadian College of Naturopathic Medicine (CCNM), Kanada, Collège Européen de Naturopathie Traditionnelle Holistique (CENATHO), Francija, Centro Andaluz de Naturopatia (CEAN), Španija, Naturopatska šola (SAEKA), Slovenija, Wellpark College of Natural Therapies, Nova Zelandija. Prav tako bi se radi zahvalili posameznikom in organizacijam, ki so sodelovali pri dveh predhodnih raziskavah, ki sta zagotovili temelje za ta projekt. Te organizacije so navedene v obeh poročilih o opravljeni raziskavi, ki sta na voljo na spletnem mestu: http://worldnaturopathicfederation.org/wnf-publications/. Projekt je vodila Komisija za raziskovanje naturopatskih korenin pri SNZ, ki kot člane vključuje zdravilce oz. Heilpraktiker, naturopate in naturopatske zdravnike (ND): Tina Hausser, Heilpraktiker, naturopat - predsednica (Španija) Dr. Iva Lloyd, naturopatski zdravnik (ND) (Kanada) Dr. JoAnn Yànez, ND, MPH, CAE (Združene države) Phillip Cottingham, naturopat (Nova Zelandija) Roger Newman Turner, Naturopath (Združeno kraljestvo) Alfredo Abascal, naturopat (Urugvaj) Vse pravice pridržane. Publikacije Svetovne naturopatske zveze lahko pridobite na našem spletnem mestu: www.worldnaturopathicfederation.org. Prošnje za dovoljenje -

Benchmarks for Training in Naturopathy

Benchmarks for training in traditional / complementary and alternative medicine Benchmarks for Training in Naturopathy WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Benchmarks for training in traditional /complementary and alternative medicine: benchmarks for training in naturopathy. 1.Naturopathy. 2.Complementary therapies. 3.Benchmarking. 4.Education. I.World Health Organization. ISBN 978 92 4 15996 5 8 (NLM classification: WB 935) © World Health Organization 2010 All rights reserved. Publications of the World Health Organization can be obtained from WHO Press, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel.: +41 22 791 3264; fax: +41 22 791 4857; e-mail: [email protected] ). Requests for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications – whether for sale or for noncommercial distribution – should be addressed to WHO Press, at the above address (fax: +41 22 791 4806; e-mail: [email protected] ). The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters. All reasonable precautions have been taken by the World Health Organization to verify the information contained in this publication. -

WNF Bílá Kniha: Naturopatické Filosofie, Principy a Teorie

WNF Bílá kniha: Naturopatické filosofie, principy a teorie Poděkování Světová naturopatická federace (WNF) velmi oceňuje spolupráci následujících naturopatických vzdělávacích institucí při poskytování požadovaných údajů pro Bílou knihu WNF: Naturopatické filosofie, principy a teorie; Bastyr University, USA; Canadian College of Naturopathic Medicine (CCNM), Kanada; Collège Européen de Naturopathie Traditionnelle Holistique (CENATHO), Francie; Centro Andaluz de Naturopatía (CEAN), Španělsko; Naturopatska Sola (SAEKA), Slovinsko; Wellpark College of Natural Therapies, Nový Zéland. Rádi bychom také poděkovali jednotlivcům a organizacím, které se podílely na dvou předchozích průzkumech, které poskytly základy pro tento projekt. Tyto organizace jsou uvedeny ve dvou zprávách o průzkumu, které lze nalézt na adrese http://worldnaturopathicfederation.org/wnf-publications/. Tuto iniciativu vedl výbor WNF Naturopathic Roots (Naturopatické kořeny), který zahrnoval členy Heilpraktiker, naturopaty a naturopatické lékaře (ND): Tina Hausser, Heilpraktiker, naturopat (Španělsko) Dr. Iva Lloyd, naturopatický lékař (ND) (Kanada) Dr. JoAnn Yánez, ND, MPH, CAE (USA) Phillip Cottingham, naturopat (Nový Zéland) Roger Newman Turner, naturopat (Velká Británie) Alfredo Abascal, naturopat (Uruguay) Všechna práva vyhrazena. Publikace Světové naturopatické federace jsou k dispozici na internetových stránkách www.worldnaturopathicfederation.org. Žádosti o povolení reprodukovat nebo překládat publikace WNF - ať již pro prodej nebo pro nekomerční distribuci musí být -

Central Council for Research in Ayurvedic Sciences

CENTRAL COUNCIL FOR RESEARCH IN AYURVEDIC SCIENCES Syllabus for Ph.D. Fellowships/ Senior Research Fellowships in different AYUSH streams SI. Name of the Fellowship Syllabus/Subjects Total No. Qucstions/Marks (total marks = 120) 1. Aptitude Section (Part-I) A. General Science: All Science Subjects 30 MCQs/30 Marks common to all AYUSH (Physics, Chemistry, Biology) as per NCERT (@ 1 marks per streams on General Science Syllabus for 10+2. question) and Research aptitude (for B. Research aptitude including Research Ph.D. Fellowship/Senior Methodology: Research Methodology with Research Fellowship) emphasis on Clinical Research Conduct & Monitoring, Good Clinical Practices, Protocol Development, Bio-ethics, Bio-statistics etc. *The questions should be applied in nature with reasoning to assess the subject knowledge and aptitude of scholars. 2. Subject Specific Section As per syllabus prescribed by Central Council of 90 MCQs/90 Marks (Part-II-A/Y/U/S/H) (for Indian Medcine (CCIM*) for Ayurveda, Siddha (@ 1 marks per Ph.D. Fellowship/Senior & Unani at SI. No.2.1-2.3 and by Central question) Research Fellowship) Council of Homoeopathy (CCH*) for Homoeopathy at SI. No.2.4, and provide by Central Council for Research in Yoga & Naturopathy (CCRYN) for Yoga & Naturopathy at SI. No.2.5. 2.1 Ph.D. Fellowship/Senior All subjects of under Graduation (BAMS) as per 90 MCQs/90 Marks Research Fellowship CCIM* syllabus (@ 1 marks per (Ayurveda) *The questions should be applied in nature with question) reasoning to assess the subject knowledge and aptitude of postgraduate level scholars. 2.2 Ph.D. Fellowship/Senior All subjects of under Graduation (BSMS) as per 90 MCQs/90 Marks Research Fellowship CCIM* syllabus (@ 1 marks per (Siddha) *The questions should be applied in nature with question) reasoning to assess the subject knowledge and aptitude of postgraduate level scholars. -

Prebiotics & Metabolic Regulation Psychiatric Disorders

DOCERE US Cannabis Regulation: What It NATUROPATHIC DOCTOR NEWS & REVIEW Means for Naturopathic Doctors ...... >>10 VOLUME 15 ISSUE 1 JANUARY 2019 | GASTROINTESTINAL HEALTH / TOXICOLOGY / BARIATRIC Shaon Hines, ND Laws around marijuana and hemp are confusing. Dr Hines’ article helps to clarify the issues. FUT2 Secretor Status: Tolle Totum Effects on Gut Health ........................ >>16 Ginger Nash, ND The gene controlling secretion of ABO antigens into Prebiotics & bodily fluids highly impacts GI function. EDUCATION Medical Resources for NDs: Metabolic Regulation A Review of Current Publications for the Naturopathic Industry ........... >>13 Blaine Harbourne, ND, LDN, CNS, CSCS Benefits Beyond the Gut Dr Morstein’s book on diabetes is a valuable resource for both patients and practitioners. Naturopathic Medical Education: ERICK R. CERVANTES, MPH, ND What a Russian Soldier Taught Me DALE PFOST, PHD About Its Value Proposition ............... >>28 David J. Schleich, PhD uman beings are host to a diverse Weaving traditional values into worrying trends will keep the medicine defined in tough terrain. Hecosystem known as the microbiome. Characteristic of our microbiome, among many other things, is its now well-known TOLLE CAUSAM diversity within the individual and from Autoimmunity & GI Disorders: person to person, as well as its vast array Sorting Out the Triggers .................... >>14 of elaborate influences on our physiology. Chad Larson, NMD, DC, CCN, CSCS Dr Larson reviews models of immune dysregulation Our scientific knowledge of this symbiotic and how to nail responsible triggers. ecosystem has grown tremendously, and its clinical significance and implications cannot Clostridia & Constipation: Using Organic Acid Testing in be ignored. This paper highlights how some Diagnosis & Treatment ..................... -

Naturopathic Physical Medicine

Naturopathic Physical Medicine Publisher: Sarena Wolfaard Commissioning Editor: Claire Wilson Associate Editor: Claire Bonnett Project Manager: Emma Riley Designer: Charlotte Murray Illustration Manager: Merlyn Harvey Illustrator: Amanda Williams Naturopathic Physical Medicine THEORY AND PRACTICE FOR MANUAL THERAPISTS AND NATUROPATHS Co-authored and edited by Leon Chaitow ND DO Registered Osteopath and Naturopath; Former Senior Lecturer, University of Westminster, London; Honorary Fellow, School of Integrated Health, University of Westminster, London, UK; Fellow, British Naturopathic Association With contributions from Additional contributions from Eric Blake ND Hal Brown ND DC Nick Buratovich ND Paul Orrock ND DO Michael Cronin ND Matthew Wallden ND DO Brian Isbell PhD ND DO Douglas C. Lewis ND Co-authors of Chapter 1: Benjamin Lynch ND Pamela Snider ND Lisa Maeckel MA CHT Jared Zeff ND Carolyn McMakin DC Foreword by Les Moore ND Joseph Pizzorno Dean E. Neary Jr ND Jr ND Roger Newman Turner ND DO David Russ DC David J. Shipley ND DC Brian K. Youngs ND DO Edinburgh London New York Oxford Philadelphia St Louis Sydney Toronto 2008 © 2008, Elsevier Limited. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior per- mission of the Publishers. Permissions may be sought directly from Elsevier’s Health Sciences Rights Department, 1600 John F. Kennedy Boulevard, Suite 1800, Philadelphia, PA 19103-2899, USA: phone: (+1) 215 239 3804; fax: (+1) 215 239 3805; or, e-mail: [email protected]. You may also com- plete your request on-line via the Elsevier homepage (http://www.elsevier.com), by selecting ‘Support and contact’ and then ‘Copyright and Permission’. -

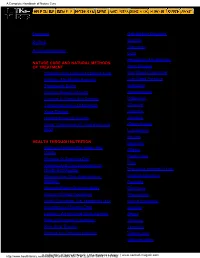

A Complete Handbook of Nature Cure

A Complete Handbook of Nature Cure Contents Foreword 49. Gall-Bladder Disorders 50. Gastritis Preface 51. Glaucoma Acknowledgements 52. Gout PART I . 53. Headaches And Migraine NATURE CURE AND NATURAL METHODS 54. Heart Disease OF TREATMENT 1. Principles And Practice Of Nature Cure 55. High Blood Cholesterol 2. Fasting - The Master Remedy 56. High Blood Pressure 3. Therapeutic Baths 57. Hydrocele 4. Curative Powers Of Earth 58. Hypoglycemia 5. Exercise In Health And Disease 59. Indigestion 6. Therapeutic Value Of Massage 60. Influenza 61. Insomnia 7. Yoga Therapy 8. Healing Power Of Colours 62. Jaundice 9. Sleep : Restorative Of Tired Body And 63. Kidney Stones Mind 64. Leucoderma 65. Neuritis PART II HEALTH THROUGH NUTRITION 66. Nepthritis Optimum Nutrition For Vigour And 10. 67. Obesity Vitality 68. Peptic Ulcer 11. Miracles Of Alkalizing Diet 69. Piles 12. Vitamins And Their Importance In Health And Disease 70. Premature Greying Of Hair 13. Minerals And Their Importance In 71. Prostate Disorders Nutrition. 72. Psoriasis 14. Amazing Power Of Amino Acids 73. Pyorrhoea 15. Secrets Of Food Combining 74. Rheumatism 16. Health Promotion The Vegetarian Way Sexual Impotence 75. 17. Importance Of Dietary Fibre 76. Sinusitis 18. Lecithin - An Amazing Youth Element 77. Stress 19. Role Of Enzymes In Nutrition. 78. Thinness 20. Raw Juice Therapy 79. Tonsillitis 21. Sprouts For Optimum Nutrition 80. Tuberculosis PART III 81. Varicose Veins http://www.healthlibrary.com/reading/ncure/index.htmA Collection of Sacred M (1a gofic 2)k |[5/19/1999 The Eso t9:11:19eric Lib PM]rary | www.sacred-magick.com A Complete Handbook of Nature Cure DISEASES AND THEIR NATURAL 82. -

Philosophy of Natural Therapeutics

^J^^?^j^y#^:^ sl#-?5# PHILOSOPHY OF NATim THERAPEUTICS Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 http://www.archive.org/details/philosophyofnatuOOIind /U.d. NATURAL THERAPEUTICS, VOL. I PHILOSOPHY OF NATURAL THERAPEUTICS HENRY LINDLAHR, M. D. FIFTH EDITION Published by The Lindlahr Publishing Co. (Not Incorporated) 515-529 South Ashland Boulevard CHICAGO 1924 Copyright, 1918, by Henry Lindlahr, M. D. COPYEIGHT, 1919, by Henry Lindlahr, M. D. AU rights reserved CONTENTS. CHAPTER PAGE Announcement vii To Progressive Physicians of the Age 1 The Upas Tree of Disease 8 I. Missing Links 9 II. What Is Nature Cure? 18 III. Catechism of Nature Cure 22 IV. What Is Life? 28 V. The Primary Cause of Disease and Its Manifestations 37 VI. The Unity of Acute Disease 49 VII. The Laws of Cure 60 Vm. Suppression versus Elimination 68 IX. Inflammation 82 X The Discovery of Microzyma 100 XL Eesults of Suppression 110 Xn. Surgery 122 XIII. Appendicitis 129 XIV. Vaccination 145 XV. The Diphtheria Antitoxin 169 XVI. Suppressive Surgical Treatment of Tonsilitis and Enlarged Adenoids 181 XVII. Woman 's Suffering 187 XVin. Cancer 202 XIX. What About the Chronic? 227 XX. Diagnosis and Prognosis 236 XXI. Treatment of Chronic Diseases 244 iii £v CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE XXII. Crises 255 XXIII. Periodicity 267 XXIV. The True Scope of Medicine 289 XXV. Homeopathy 307 XXVI. Natural Dietetics 319 XXVn. Fasting 322 XXVIII. What Is Positive, What Is Negative? 332 XXIX. Health Is Positive, Disease Negative 344 XXX. Conservation of Vitality 370 XXXI. Onanism or Masturbation 387 XXXII. Spinal Manipulation and Adjustment 399 XXXni. -

The Legacy of Sebastian Kneipp: Linking Wellness, Naturopathic, and Allopathic Medicine

THE JOURNAL OF ALTERNATIVE AND COMPLEMENTARY MEDICINE Volume 20, Number 7, 2014, pp. 521–526 Paradigms ª Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. DOI: 10.1089/acm.2013.0423 The Legacy of Sebastian Kneipp: Linking Wellness, Naturopathic, and Allopathic Medicine Cornelia Locher, PhD,1 and Christof Pforr, PhD2 Abstract Sebastian Kneipp (1821–1897) is seen as a vital link between the European nature cure movement of the 19th century and American naturopathy. He promoted a holistic treatment concept founded on five pillars: hydro- and phytotherapy, exercise, balanced nutrition, and regulative therapy. Kneipp attempted to bridge the gap with allopathic medicine, and many modern treatments that are based on his methods indeed blend wellness elements with naturopathic medicine and biomedicine. Because Kneipp’s approach to health and healing today are mainly covered in German literature, this paper aims to provide a broader international audience with insights into his life and his treatment methods and to highlight the profound influence Kneipp has had to this day on natural and preventive medicine. The paper emphasizes in particular the continued popularity of Kneipp’s holistic approach to health and well-being, which is evident in the many national and international Kneipp Associations, the globally operating Kneipp Werke, postgraduate qualifications in his treatment methods, and the existence of more than 60 accredited Kneipp spas and health resorts in Germany alone. Introduction in hundreds of accredited Kneipp spas and health resorts across Europe. In Germany, -

Nature Cure: Philosophy & Practice Based on the Unity of Disease & Cure

Nature Cure by Henry Lindlahr, MD, 1913 A Free Ebook from http://www.pulsemed.org/ Email it to others yourself, or send them to PulseMed.org to get it! Nature Cure: Philosophy & Practice Based on the Unity of Disease & Cure Henry Lindlahr, M.D. This Free E-Book is Presented As Is Without Guarantee or Warranty. Consult Your Local Healthcare Practitioner Before Trying New Health Remedies. Visit www.PulseMed.org for Alternative Medicine That Works For Regular Folks! Nature Cure by Henry Lindlahr, MD, 1913 A Free Ebook from http://www.pulsemed.org/ Email it to others yourself, or send them to PulseMed.org to get it! This E-Book is a free gift to you from The Pulse of Oriental Medicine website (http://www.pulsemed.org/), home to Alternative Medicine That Works for Regular Folks, more than 400,000 of whom have visited and read our more than 350 free articles. Please pass this E-Book on to your friends, family members, and anyone else you think would enjoy it. If it proves too large to email, you can send them to xxx to download it free of charge. Why are we giving you a free E-Book? Because we think you might like to read it, because we hope you will remember to stop by PulseMed.org for more information about Alternative Medicine, acupuncture, herbs, prevention, healing, diseases, etc., and because we hope you will pass it on to others. We hope you enjoy the book. Stop by http://www.pulsemed.org/ and let us know what you think of it! This Free E-Book is Presented As Is Without Guarantee or Warranty.