Life of Pikelet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The British Isles

The British Isles Historic Society Heritage, History, Traditions & Customs OUR BRITISH ISLES HERITAGE houses the countries of England, Scotland and Wales within its shores. The British Isles The British Isles is the name of a group of islands situated off the north western corner of mainland Europe. It is made up of Great Britain, Ireland, The Isle of Man, The Isles of Sicily, The Channel Islands (including Guernsey, Jersey, Sark Dear Readers: and Alderney), as well as over 6,000 other smaller I know some of the articles in this Issue may islands. England just like Wales (Capital - Cardiff) and seem like common sense and I am researching facts Scotland (Capital - Edinburgh), North Ireland (Capital known by everyone already. But this newsletter has - Belfast) England is commonly referred to as a a wider distribution than just Ex-Pats. country, but it is not a sovereign state. It is the largest country within the United Kingdom both by Many believe Britain or Great Britain to be all landmass and population, has taken a role in the the islands in the British Isles. When we held the two creation of the UK, and its capital London is also the Heritage Festivals we could not call it a British capital of the UK. Festival because it included, England, Scotland, Ireland, Wales, Cornwall and the Isle of Man. The Republic of Ireland (EIRE) Republic of What is the Difference between Britain and the Ireland is part of the British Isles, its people are not United Kingdom? British, they are distinctly Irish. It’s capital is Dublin. -

Bakery and Confectionary HM-302 UNIT: 01 HISTORICAL BACKGROUND of BAKING

Bakery and Confectionary HM-302 UNIT: 01 HISTORICAL BACKGROUND OF BAKING STRUCTURE 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Objective 1.3 Historical Background of Baking 1.4 Introduction to Large, Small Equipments and Tools 1.5 Wheat 1.5.1 Structure of Wheat 1.5.2 Types of Flour 1.5.3 Composition Of Flour 1.5.4 WAP of Flour 1.5.5 Milling of Wheat 1.5.6 Differences Between Semolina, Whole Wheat Flour And Refined Flour 1.5.7 Flour Testing 1.6 Summary 1.7 Glossary 1.8 Reference/Bibliography 1.9 Terminal Questions 1.1 INTRODUCTION BREAD!!!!…….A word of many meanings, a symbol of giving, one food that is common to so many countries….but what really is bread ????. Bread is served in various forms with any meal of the day. It is eaten as a snack, and used as an ingredient in other culinary preparations, such as sandwiches, and fried items coated in bread crumbs to prevent sticking. It forms the bland main component of bread pudding, as well as of stuffing designed to fill cavities or retain juices that otherwise might drip out. Bread has a social and emotional significance beyond its importance as nourishment. It plays essential roles in religious rituals and secular culture. Its prominence in daily life is reflected in language, where it appears in proverbs, colloquial expressions ("He stole the bread from my mouth"), in prayer ("Give us this day our daily bread") and in the etymology of words, such as "companion" (from Latin comes "with" + panis "bread"). 1.2 OBJECTIVE The Objective of this unit is to provide: 1. -

![BBC Voices Recordings: Nottingham [Meadows]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2893/bbc-voices-recordings-nottingham-meadows-342893.webp)

BBC Voices Recordings: Nottingham [Meadows]

BBC VOICES RECORDINGS http://sounds.bl.uk Title: Nottingham Shelfmark: C1190/26/05 Recording date: 17.11.2004 Speakers: Amelia, b. 1963; Nottingham; female (father b. St Kitts; mother b. St Kitts) Lauren, b. 1989; Nottingham; female; school student Rosalind, b. 1964; Nottingham; female (father b. St Kitts; mother b. St Kitts) Valerie, b. 1965; Nottingham; female (father b. St Kitts; mother b. St Kitts) Amelia, Rosalind and Valerie are sisters whose parents came to the UK from St Kitts in the 1950s; Lauren is their niece. ELICITED LEXIS ○ see English Dialect Dictionary (1898-1905) ▲see Dictionary of Jamaican English (1980) ● see Dictionary of Caribbean English Usage (1996) ♠ see Dictionary of the English/Creole of Trinidad & Tobago (2009) ▼ see Ey Up Mi Duck! Dialect of Derbyshire and the East Midlands (2000) ∆ see New Partridge Dictionary of Slang and Unconventional English (2006) ◊ see Green’s Dictionary of Slang (2010) ♦ see Urban Dictionary (online) ⌂ no previous source (with this sense) identified pleased (not discussed) tired (not discussed) unwell sick; “me na feel too good”1 (used by mother/older black speakers) hot (not discussed) cold (not discussed) annoyed (not discussed) throw (not discussed) 1 See Dictionary of Caribbean English Usage (1996, p.407) for use of ‘no/na’ as negative marker in Caribbean English and for spelling of markedly dialectal/Creole pronunciations, e.g. the (<de>), there (<deh>). http://sounds.bl.uk Page 1 of 27 BBC Voices Recordings play truant skive; nick off∆; skank◊; wag, wag off school, wag off (suggested -

Gluten Free Grains

Gluten-free Grains A demand-and-supply analysis of prospects for the Australian health grains industry A report for the Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation by Grant Vinning and Greg McMahon Asian Markets Research Pty Ltd September 2006 RIRDC publication no. 05/011 RIRDC project no. AMR–10A © 2006 Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation All rights reserved ISBN 1 74151 110 0 ISSN 1440-6845 Gluten-free Grains: a demand-and-supply analysis of prospects for the Australian grains industry Publication no. 05/011 Project no. AMR–10A The information contained in this publication is intended for general use to assist public knowledge and discussion and to help improve the development of sustainable industries. The information should not be relied upon for the purpose of a particular matter. Specialist and/or appropriate legal advice should be obtained before any action or decision is taken on the basis of any material in this document. The Commonwealth of Australia, the Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation, and the authors or contributors do not assume liability of any kind whatsoever resulting from any person’s use of or reliance on the content of this document. This publication is copyright. However, RIRDC encourages wide dissemination of its research results, providing the Corporation is clearly acknowledged. For any inquiries concerning reproduction, telephone the Publications Manager on 02 6272 3186. Researcher contact details Grant Vinning Greg McMahon Asian Markets Research Asian Markets Research 22 Kersley Road 22 Kersley Road KENMORE QLD 4069 KENMORE QLD 4069 Phone: 07 3378 0042 Phone: 07 3378 0042 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] In submitting this report, the researchers have agreed to RIRDC publishing this material in its edited form. -

Baking Problems Solved Related Titles

Baking Problems Solved Related Titles Steamed Breads: Ingredients, Processing and Quality (ISBN: 978-0-08-100715-0) Cereal Grains, 2e (ISBN: 978-0-08-100719-8) Cereal Grains for the Food and Beverage Industries (ISBN: 978-0-85709-413-1) Baking Problems Solved Second Edition Stanley P. Cauvain Woodhead Publishing is an imprint of Elsevier The Officers’ Mess Business Centre, Royston Road, Duxford, CB22 4QH, United Kingdom 50 Hampshire Street, 5th Floor, Cambridge, MA 02139, United States The Boulevard, Langford Lane, Kidlington, OX5 1GB, United Kingdom Copyright r 2017 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Details on how to seek permission, further information about the Publisher’s permissions policies and our arrangements with organizations such as the Copyright Clearance Center and the Copyright Licensing Agency, can be found at our website: www.elsevier.com/permissions. This book and the individual contributions contained in it are protected under copyright by the Publisher (other than as may be noted herein). Notices Knowledge and best practice in this field are constantly changing. As new research and experience broaden our understanding, changes in research methods, professional practices, or medical treatment may become necessary. Practitioners and researchers must always rely on their own experience and knowledge in evaluating and using any information, methods, compounds, or experiments described herein. In using such information or methods they should be mindful of their own safety and the safety of others, including parties for whom they have a professional responsibility. -

Introduction to Baking and Pastries Chef Tammy Rink with William R

Introduction to Baking and Pastries Chef Tammy Rink With William R. Thibodeaux PH.D. ii | Introduction to Baking and Pastries Introduction to Baking and Pastries | iii Introduction to Baking and Pastries Chef Tammy Rink With William R. Thibodeaux PH.D. iv | Introduction to Baking and Pastries Introduction to Baking and Pastries | v Contents Preface: ix Introduction to Baking and Pastries Topic 1: Baking and Pastry Equipment Topic 2: Dry Ingredients 13 Topic 3: Quick Breads 23 Topic 4: Yeast Doughs 27 Topic 5: Pastry Doughs 33 Topic 6: Custards 37 Topic 7: Cake & Buttercreams 41 Topic 8: Pie Doughs & Ice Cream 49 Topic 9: Mousses, Bavarians and Soufflés 53 Topic 10: Cookies 56 Notes: 57 Glossary: 59 Appendix: 79 Kitchen Weights & Measures 81 Measurement and conversion charts 83 Cake Terms – Icing, decorating, accessories 85 Professional Associations 89 vi | Introduction to Baking and Pastries Introduction to Baking and Pastries | vii Limit of Liability/disclaimer of warranty and Safety: The user is expressly advised to consider and use all safety precautions described in this book or that might be indicated by undertaking the activities described in this book. Common sense must also be used to avoid all potential hazards and, in particular, to take relevant safety precautions concerning likely or known hazards involving food preparation, or in the use of the procedures described in this book. In addition, while many rules and safety precautions have been noted throughout the book, users should always have adult supervision and assistance when working in a kitchen or lab. Any use of or reliance upon this book is at the user's own risk. -

In Re Grupo Bimbo, S.A.B. De C.V. _____

This Opinion Is Not a Precedent of the TTAB Precedent of the TTAB Hearing: March 11, 2021 PrePrecedent of the TTAB Mailed: April 14, 2021 UNITED STATES PATENT AND TRADEMARK OFFICE _____ Trademark Trial and Appeal Board _____ In re Grupo Bimbo, S.A.B. de C.V. _____ Application Serial No. 87408465 _____ Jeffrey A. Handelman, Andrew J. Avsec, and Virginia W. Marino of Brinks Gilson & Lione for Grupo Bimbo, S.A.B. de C.V. Tamara Hudson, Trademark Examining Attorney, Law Office 104, Zachary Cromer, Managing Attorney. _____ Before Mermelstein, Bergsman and Lebow, Administrative Trademark Judges. Opinion by Bergsman, Administrative Trademark Judge: Grupo Bimbo, S.A.B. de C.V. (Applicant) seeks registration on the Principal Register of the term ARTESANO, in standard character form, for goods amended to read as “pre-packaged sliced bread,” in International Class 30.1 Applicant included a translation of the word ARTESANO as “craftsman.” 1 Serial No. 87408465 filed April 12, 2017, under Section 1(a) of the Trademark Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1051(a), based on Applicant’s claim of first use of its mark anywhere and in commerce as of August 31, 2015. Serial No. 87408465 The Examining Attorney refused to register ARTESANO under Sections 1, 2, and 45 of the Trademark Act, 15 U.S.C. §§ 1051-1052 and 1127, on the ground that ARTESANO for “pre-packaged sliced bread” is generic and, in the alternative, that it is merely descriptive under Section 2(e)(1) of the Trademark Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1052(e)(1), and has not acquired distinctiveness under Section 2(f) of the Trademark Act, 15 U.S.C. -

Guardian and Observer Editorial

guardian.co.uk/guides Welcome | 3 Dan Lepard 12 • Before you start 8 Yes, it’s true, baking is back. And • Meet the baker 12 whether you’re a novice pastry • Bread recipes 13 • Cake 41 roller or an expert icer, our • Pastry 69 scrumptious 100-page guide will • Baking supplies 96 take your enjoyment of this relaxing and (mostly) healthy pursuit to a whole new level. We’ve included the most mouthwatering bread, cake and pastry recipes, courtesy of our Tom Jaine 14 baking maestro Dan Lepard and a supporting cast of passionate home bakers and chefs from Rick Stein and Marguerite Patten to Ronnie Corbett and Neneh Cherry. And if Andi and Neneh 42 you’re hungry for more, don’t miss tomorrow’s Observer supplement on baking with kids, and G2’s exclusive series of gourmet cake recipes all next week. Now get Ian Jack 70 KATINKA HERBERT, TALKBACK TV, NOEL MURPHY your pinny on! Editor Emily Mann Executive editor Becky Gardiner All recipes by Dan Lepard © 2007 Additional editing David Whitehouse Recipe testing Carol Brough Art director Gavin Brammall Designer Keith Baker Photography Jill Mead Picture editor Marissa Keating Production editor Pas Paschali Subeditor Patrick Keneally Staff writer Carlene Thomas-Bailey Production Steve Coady Series editor Mike Herd Project manager Darren Gavigan Imaging GNM Imaging Printer Quebecor World Testers Kate Abbott, Keith Baker, Diana Brown, Nell Card, Jill Chisholm, Charlotte Clark, Margaret Gardner, Sarah Gardner, Barbara Griggs, Liz Johns, Marissa Keating, Patrick Keneally, Adam Newey, Helen Ochyra, Joanna Rodell, John Timmins, Ian Whiteley Cover photograph Alexander Kent Woodcut illustration janeillustration.co.uk If you have any comments about this guide, please email [email protected] To order additional copies of this Guardian Guide To.. -

Strand 1: Physical Systems PS.2.1 Recognize the Differences and Similarities of Solids, Liquids, and Gases

Strand 1: Physical Systems PS.2.1 Recognize the differences and similarities of solids, liquids, and gases. PS.2.2 Understand the physical properties of objects. PS.2.3 Learn about the physical world by observing, data collecting, using age appropriate tools, describing, and hypothesizing. PS.2.4 Revise hypothesis by sharing and communicating observations through writing. Science Task 1 Materials Needed: Book about solids, liquids, and gases, water, ice trays, pot, small range, cups, science task 1, 2 category cards, 10 word cards, 10 picture cards. Lesson: Teacher reads the book about solids, liquids, and gases. Discuss how water is a liquid and brainstorm other items that are liquids. Pour ½ of the water into the ice trays and place in freezer. Pour ½ of the water into the pot, place on the range; observe what happens to the water when it gets hot. Discuss what is happening to the water. Teacher writes children responses on a chart. Check the water in the freezer. Discuss what happens to the water when it freezes. It becomes a solid. Give each child an ice cube and a cup. Place the ice cube in the cup. Make a hypothesis about what will happen to the ice. Record the hypotheses. Model how to hold hands around the cup and blow on the ice. Children follow and provide heat with hands around the cup and blow on the ice. Observe what happens as the ice is melting. Teacher models how to describe what happens to the ice. Children write about what they observed. Introduce Science Task 1 Science Task 1 Line up the category cards. -

Of 4 07/12/2015

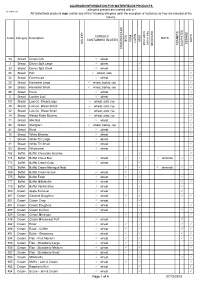

ALLERGEN INFORMATION FOR WATERFIELDS PRODUCTS - allergens present are marked with a NETHERTON All Waterfields products may contain any of the following allergens (with the exception of molluscs) as they are handled at the bakery. CEREALS Code Category Description NUTS CONTAINING GLUTEN EGG FISH MILK SOYA LUPIN CELERY SESAME (not on site) PEANUTS MOLLUSCS MUSTARD SULPHITES CRUSTACEANS 34 Bread Crown Cob wheat 3 Bread Devon Split Large wheat 33 Bread Devon Split Small wheat 85 Bread Farl wheat, oats 32 Bread Farmhouse wheat 20 Bread Harvester Large wheat, barley, rye 84 Bread Harvester Small wheat, barley, rye 86 Bread Hovis wheat 2 Bread London Loaf wheat 107 Bread Low G.I. Bread Large wheat, oats, rye 48 Bread Low G.I. Bread Sliced wheat, oats, rye 42 Bread Low G.I. Bread Small wheat, oats, rye 14 Bread Malted Flake Bloomer wheat, oats, rye 71 Bread Milk Roll wheat 88 Bread Multigrain wheat, barley, rye 41 Bread Rural wheat 16 Bread White Bloomer wheat 1 Bread White Tin Large wheat 31 Bread White Tin Small wheat 53 Bread Wholemeal wheat 782 Buffet Buffet Chocolate Surprise 774 Buffet Buffet Choux Bun wheat almonds 773 Buffet Buffet Cream Crisp wheat 778 Buffet Buffet Cream Meringue Nest almonds 786 Buffet Buffet Cream Scone wheat 775 Buffet Buffet Éclair wheat 777 Buffet Buffet Millefeuille wheat 776 Buffet Buffet Vanilla Slice wheat 500 Cream Apple Turnover wheat 467 Cream Caramel Doughnut wheat 501 Cream Cream Crisp wheat 481 Cream Cream Doughnut -

Bloomers-Bakery-Brochure.Pdf

ACTUAL ARTWORK:Layout 1 18/10/10 09:25 Page 1 Unit 3c Soulton Road Industrial Estate Unit 10, Rivulet Road Wem, Shropshire SY4 5SD Wrexham LL13 8DL Tel: 01939 236200 Tel: 01978 265064 Fax: 01939 236375 Order Line: 01978 355090 Mobile No. 07576 613210 All orders must be placed before 3:00pm the day before they are required. Any orders after 3:00pm cannot be guaranteed. We reserve the right to deny supply to customers with outstanding accounts. All sizes, shapes, colours and designs indicated in this brochure are approximate and we reserve the right to change them without prior notice. However every accommodation will be made to ensure our customers are not inconvenienced in any way. Brochure design by ENSO Design Communications 07974 773685 ACTUAL ARTWORK:Layout 1 18/10/10 09:26 Page 3 Cream Nutty Fresh Cream Scone One of our excellent plain scones with a fresh cream filling and a dusting of icing Who we are sugar. Superb value. Light puff pastry with fresh cream filling and a generous sprin- kling of roasted almonds and icing sugar on top. Carolines was founded in 1971 by my grandmother Mrs Elsie Hughes. Originally they had a shop in the Central Arcade in Wrexham and Long Chocolate doughnut Choux Puff another one in Bridge Street, Wrexham, with a A delicious long small ‘bake house’ behind. Four years later a third doughnut filled shop was acquired in Oswestry, Shropshire. When with fresh cream, a blob of strawberry my grandmother first opened this shop she was jam and a rich chocolate topping. -

Download an Infographic Showcasing the Poll Results Here

Consumers Eating More Baked Goods During Pandemic RESEARCH SUMMARY COOKIES BREAD CAKE DONUTS BROWNIES MUFFINS CUPCAKES BISCUITS SCONES More than 1 in 4 57% 50% 42% 36% 35% 31% 29% 27% 10% Americans (28%) have been 28% eating more baked goods than Cookies (57%), bread (50%) and cake (42%) top the list of baked goods they normally would as a result of the Americans have been eating as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic over the COVID-19 pandemic over the past 6 months. past 6 months. Consumers are eating more baked goods in the past six months as a result of COVID-19 because. I’m giving Helps me myself escape the Reminds permission reality of me of to indulge what is Meets a Sense of Induces good during going on in craving comfort happiness times this time the world 48% 42% 41% 30% 27% 26% What's the Appetite for Baked TIPS TO BAKE UP MORE SALES Goods When Dining Out? Bake up happiness. Give patrons more of what they want by menuing a variety of More than two thirds of Americans (68%) are the top baked goods that consumers are more tempted to buy baked goods when dining seeking right now. out if they know they are baked fresh onsite than if they are prepared offsite. Promote items baked fresh onsite. Use social media, menu boards, signage 77% said the smell of fresh baked items and more to let your customers know that items are baked fresh onsite. or seeing fresh items on display enticed them to purchased baked goods.