I) Attention Is Drawn to the Fact That the Copyright of a Thesis Rests with Its Author. Requests for Such Permission Should Be A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ENEL — Società Per Azioni (Incorporated with Limited Liability in Italy) U.S

OFFERING CIRCULAR NOT FOR GENERAL CIRCULATION IN THE UNITED STATES ENEL — Società per Azioni (incorporated with limited liability in Italy) U.S. $1,250,000,000 Capital Securities due 2073 Enel — Società per Azioni (the “Issuer” or “Enel”) will issue U.S. $1,250,000,000 Capital Securities due 2073 (the “Securities”) on September 24, 2013 (the “Issue Date”). The Securities will bear interest on their principal amount (a) from (and including) the Issue Date to (but excluding) the First Reset Date, at the rate of 8.750 percent per annum and (b) from (and including) the First Reset Date to (but excluding) the Maturity Date, for each Reset Period, the relevant 5-year Swap Rate plus (A) in respect of the Reset Periods commencing on the First Reset Date, September 24, 2028, September 24, 2033 and September 24, 2038, 6.130 percent per annum, and (B) in respect of any other Reset Period, 6.880 percent per annum (each, as defined in “Description of the Securities”). Interest on the Securities will be payable semi- annually in arrears on March 24 and September 24 each year, commencing on March 24, 2014 (each an “Interest Payment Date”). Payment of interest on the Securities may be deferred at the option of the Issuer in certain circumstances, as set out under “Description of the Securities — Interest Deferral”. The Securities will be issued in fully registered form and only in denominations of U.S. $200,000 and in integral multiples of U.S. $1,000 in excess thereof. Unless previously redeemed by the Issuer as provided below, the Issuer will redeem the Securities on September 24, 2073 at their principal amount, together with interest accrued to, but excluding, such date and any Arrears of Interest (as defined in “Description of the Securities”). -

F-MARC Football Medicine Manual 2Nd Edition F-MARC Football Medicine Manual 2Nd Edition 2 Editors - Authors - Contributors | Football Medicine Manual

F-MARC Football Medicine Manual 2nd Edition F-MARC Football Medicine Manual 2nd Edition 2 Editors - Authors - Contributors | Football Medicine Manual Football Medicine Manual Editors DVORAK Jiri Prof. Dr F-MARC, Schulthess Clinic Zurich, Switzerland JUNGE Astrid Dr F-MARC, Schulthess Clinic Zurich, Switzerland GRIMM Katharina Dr FIFA Medical Offi ce Zurich, Switzerland Authors 2nd Edition 2009 ACKERMAN Kathryn E. Harvard Medical School Harvard, USA BABWAH Terence Dr Sports Medicine and Injury Rehabilitation Clinic Macoya, Trinidad BAHR Roald Prof. Dr Oslo Sports Trauma Research Center Oslo, Norway BANGSBO Jens Prof. Dr University of Copenhagen Copenhagen, Denmark BÄRTSCH Peter Prof. Dr University of Heidelberg Heidelberg, Germany BIZZINI Mario PT Schulthess Clinic Zurich, Switzerland CHOMIAK Jiri Dr Orthopaedic University Hospital Bulovka Prague, Czech Republic DVORAK Jiri Prof. Dr F-MARC, Schulthess Klinik Zurich, Switzerland EDWARDS Tony Dr Adidas Sports Medicine Auckland, New Zealand ENGEBRETSEN Lars Prof. Dr Oslo Sports Trauma Research Center Oslo, Norway FULLER Colin Prof. Dr University of Nottingham Nottingham, England GRIMM Katharina Dr FIFA Medical Offi ce Zurich, Switzerland JUNGE Astrid Dr F-MARC, Schulthess Clinic Zurich, Switzerland KHAN Karim Prof. Dr Editor in Chief British Journal of Sports Medicine Sydney, Australia Editors - Authors - Contributors | Football Medicine Manual 3 KOLBE John Prof. Dr University of Auckland Auckland, New Zealand LÜSCHER Thomas Prof. Dr University of Zurich Zurich, Switzerland MANDELBAUM Bert Dr Santa Monica Orthopaedic and Sports Medicine Group Santa Monica, USA MAUGHAN Ron Prof. Dr University of Loughborough Loughborough, Great Britain PETERSON Lars Prof. Dr Gothenburg Medical Center Gothenburg, Sweden REILLY Thomas Prof. Dr Liverpool John Moores University Liverpool, Great Britain SALTIN Bengt Prof. -

Movement Demands of Elite Rugby League Players During Australian National Rugby League and European Super League Matches

International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 2014, 9, 925-930 http://dx.doi.org/10.1123/ijspp.2013-0270 © 2014 Human Kinetics, Inc. www.IJSPP-Journal.com ORIGINAL INVESTIGATION Movement Demands of Elite Rugby League Players During Australian National Rugby League and European Super League Matches Craig Twist, Jamie Highton, Mark Waldron, Emma Edwards, Damien Austin, and Tim J. Gabbett Purpose: This study compared the movement demands of players competing in matches from the elite Australian and European rugby league competitions. Methods: Global positioning system devices were used to measure 192 performances of forwards, adjustables, and outside backs during National Rugby League (NRL; n = 88) and European Super League (SL; n = 104) matches. Total and relative distances covered overall and at low (0–3.5 m/s), moderate (3.6–5 m/s), and high (>5 m/s) speeds were measured alongside changes in movement variables across the early, middle, and late phases of the season. Results: The relative distance covered in SL matches (95.8 ± 18.6 m/min) was significantly greater (P < .05) than in NRL matches (90.2 ± 8.3 m/min). Relative low-speed activity (70.3 ± 4.9 m/min vs 75.5 ± 18.9 m/min) and moderate-speed running (12.5 ± 3.3 m m/min vs 14.2 ± 3.8 m/min) were highest (P < .05) in the SL matches, and relative high-speed distance was greater (P < .05) during NRL matches (7.8 ± 2.1 m/min vs 6.1 ± 1.7 m/min). Conclusions: NRL players have better maintenance of high-speed running between the first and second halves of matches and perform less low- and moderate-speed activity, indicating that the NRL provides a higher standard of rugby league competition than the SL. -

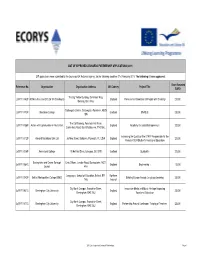

2011 List of Approved Leonardo Partnerships Page 1 Grant Awarded Reference No

LIST OF APPROVED LEONARDO PARTNERSHIP APPLICATIONS (2011) 217 applications were submitted to the Leonardo UK National Agency, for the following deadline: 21st February 2011. The following 81 were approved: Grant Awarded Reference No. Organisation Organisation Address UK Country Project Title EURO The Big Yellow Building, 25 Alfreds Way, LdVP/11/182P 3D Ministries and CO Ltd T/A Streetwyze England Professional Orientation of People with Disability 20,000 Barking, IG11 0AG Gallowgate Centre, Gallowgate, Aberdeen, AB25 LdVP/11/173P Aberdeen College Scotland ENABLE 25,000 1BN The Old Granary, Penstock Hall Farm, LdVP/11/158P Action with Communities in Rural Kent England Academy for Social Entrepreneurs 20,000 Canterbury Road, East Bradbourne, TN2 55LL Increasing the Quality of the STAFF Responsible for the LdVP/11/112P Almond Vocational Link Ltd 36 New Street, Barbican, Plymouth, PL1 2NA England 20,000 Period of SEN Student's Vocational Education LdVP/11/006P Anniesland College 19 Hatfield Drive, Glasgow, G12 0YE Scotland Qualipaths 20,000 Basingstoke and Deane Borough Civic Offices, London Road, Basingstoke, RG21 LdVP/11/084C England Engineering + 15,000 Council 4AH Languages, School of Education, Belfast, BT1 Northern LdVP/11/042P Belfast Metropolitan College (BMC) Building Europe through Language Learning 25,000 1HS Ireland City North Campus, Franchise Street, Innovative Media and Music Heritage Impacting LdVP/11/031C Birmingham City University England 25,000 Birmingham, B42 2SU Vocational Education City North Campus, Franchise Street, LdVP/11/077C Birmingham City University England Partnership Around Continuous Training of Teachers 25,000 Birmingham, B42 2SU 2011 List of approved Leonardo Partnerships Page 1 Grant Awarded Reference No. -

Una Voce JOURNAL of the PAPUA NEW GUINEA ASSOCIATION of AUSTRALIA INC (Formerly the Retired Officers Association of Papua New Guinea Inc)

ISSN 1442-6161, PPA 224987/00025 2005, No 2 - June Una Voce JOURNAL OF THE PAPUA NEW GUINEA ASSOCIATION OF AUSTRALIA INC (formerly the Retired Officers Association of Papua New Guinea Inc) Patrons: His Excellency Major General Michael Jeffery AC CVO MC (Retd) Governor-General of the Commonwealth of Australia Mrs Roma Bates; Mr Fred Kaad OBE In This Issue CHRISTMAS LUNCHEON – IN 100 WORDS OR LESS 3 This year’s Christmas Luncheon will WALK INTO PARADISE 4 be on Sunday 4 December at the NEWS FROM THE NORTHERN TERRITORY 5 Mandarin Club Sydney. We will have NEWS FROM SOUTH AUSTRALIA 6 a special theme to celebrate 30 years since PNG Independence. Look in the PNG......IN THE NEWS 7 September issue of Una Voce for Rick Nehmy reports 9 details...you will need to book early! More About Tsunami And Earthquakes 11 DONATION OF TIMBER TO MANAM ISLANDERS 14 * * * MADANG HONOURS WAR DEAD 14 VISIT TO THE MOUNTAINS EDUCATIONAL LEADERSHIP 15 The annual spring visit to the Blue MARITIME COLLEGE ACQUIRES STOREHOUSES Mountains will be on Thursday 13 15 October, 2005. Last year we were again KIAPHAT OF PORONPOSOM 16 welcomed at the spacious home of COX AND THE WENZELS 19 George and Edna Oakes at Woodford for THE SOUTH PACIFIC GAMES 20 another warm and friendly gathering. WANPELA MO BLADI ROT NA PINIS OLGERA 22 Fortunately Edna and George will be our Agricultural Development in PNG 24 hosts again this year. Full details in KOKODA TRACK AUTHORITY 26 September issue. REUNIONS 27 * * * Help Wanted 28 CPI: The CPI for our superannuation PNGAA COLLECTION - FRYER LIBRARY 29 rose 1.4% for the six months to March BOOK NEWS AND REVIEWS 30 2005 and will be paid at the end of The Lost Garrison of Rabaul 32 June. -

(Application Reference: EAC/18/2011/026) AGREEMENT

(Application reference: EAC/18/2011/026) AGREEMENT EAC-2011-xxxx ANNEX I DESCRIPTION OF THE ACTION Title of the Project: European Rugby League Governance Foundation Project Beneficiary: European Rugby European Federation Partners: Česká Asociace Rugby League Rugby League Deutschland Federazione Italiana Rugby League Latvijas Regbija Ligas Federacija Nederland Rugby League Bond Svensk Rugby League Förening Rugby Football League Fédération Française de Rugby à XIII Wales Rugby League Scotland Rugby League Rugby League Ireland Summary of the project objectives and activities: CONTEXT Since the adoption of its new constitution and eight-year strategy [both promulgated in August 2010] the RLEF is committed to disseminate best practice in the area of governance throughout its Membership, many of whom are inexperienced NGBs to whom the importance of good governance may not be immediately obvious. MAIN OBJECTIVES To address this, the Governance Foundation Project [GFP] has created a tiered Membership structure of the RLEF – Bronze [Observer status], Silver [Affiliate Member], Gold [Full Member] – where best practice and the principles of good governance will be promoted, and the cooperation between partners will develop the European dimension throughout rugby league, itself a young sport on the Continent, [foundation date of January 2003]. Use of Mentors and Learners provides innovation. ACTIVITIES In addition to utilising the Mentor-Learner system inherent in the GFP throughout a series of transnational exchanges, the project will utilise partnerships with more established European sports, namely football, to explore and cultivate good governance, using a series of seminars, technical visits and on-line tutorials and resources such as e-learning. RESULTS The objectives of the GFP are in line with the RLEF strategy, strengthening capacity building throughout and specifically elevating Learners from Bronze to Gold by project completion. -

Annual Report

2015 RFL ANNUAL REPORT 2015 RFL ANNUAL RugbyRugby FootballFootball LeagueLeague AnnualAnnual ReportReport 20152015 RFL ANNUAL REPORT FOR 2015 CEO’s Review 4-6 Further Education 29 Chairman’s View 7 Schools 30-31 Board of Directors 8-9 Rugby League Cares 32-34 120 Years 10 Play Touch RL 35 Wembley Statue 11 Concussion 36 Magic Weekend 12 Cardiac Screening 37 World Club Series 13 Player Welfare 38-40 England Review 14-15 Hall of Fame 42 THE RUGBY Domestic Season Review 16-23 Safeguarding 43 FOOTBALL LEAGUE Events Review 24-25 RLEF Review 44-45 Red Hall, Red Hall Lane, Leeds, LS17 8NB Commercial Review 26-27 Operational Plan 46-47 T: 0844 477 7113 Higher Education 28 Financial Review 48-50 www.therfl .co.uk 3 The protocol on concussion was also CHIEF EXECUTIVE updated. Players suffering a suspected concussion during a game now have to undergo a proper assessment off the fi eld, with a free interchange allowed. The sport also mourned the passing OFFICER’S REPORT of Super League Match Offi cial Chris The year 2015 represented the 120th anniversary of the This secured their second trophy of the season, having already Leatherbarrow, a talented individual who creation of the sport of Rugby League and as was fi tting for this lifted the Ladbrokes Challenge Cup with a comprehensive win over tragically died at such a young age. momentous occasion, a number of celebratory events took place Hull Kingston Rovers at Wembley. A memorable treble beckoned to appropriately acknowledge this milestone. One of the biggest and it proved to be a nailbiting climax to the season when they VIEWERS AND was the Founders Walk, a 120-mile trek which took in each of the faced Wigan Warriors in the First Utility Grand Final. -

Annual Report 2015

RUGBY LEAGUE EUROPEAN FEDERATION ANNUAL REPORT 2015 Rugby League European Federation 1 CONTENTS MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIR 3 RLEF PROFILE & VALUES 7 GENERAL MANAGER 8 COACHING MANAGER 12 MATCH OFFICIALS MANAGER 14 MEDIA MANAGER 16 Canada was edged out by the USA for the Americas berth at RLWC2017 - December GOVERNANCE 18 STRATEGY 22 RLEF COMPETITIONS 34 AFFILIATED COMPETITIONS 38 OTHER INTERNATIONALS 39 FINANCIAL REPORT 43 THE BOARD 47 APPENDIX1: ORGANISATION 49 APPENDIX 2: DOMESTIC CH. 50 Rugby league kept moving forward in Ukraine despite the political upheaval, hosting an English Lionhearts tour in Kiev - June Rugby League European Federation 2 A MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIR The twelve months covered by this annual report were, typically, full of activity in many different areas and once again demonstrated not only the increasing capability of our diverse membership but also the capacity of the RLEF as a governing body. That the federation’s name is a misnomer is well documented, with our European territories joined by American, Caribbean, African and Middle Eastern nations, and 2015 certainly ensured that the RLEF was active in its farthest outposts. At the end of the year, two more nations qualified for the 2017 Rugby League World Cup following historic firsts, not just for the RLEF but for the sport itself. Compared with the previous tournament in 2013, the qualifying events administered by the RLEF increased from two to three, with the Atlantic group replaced by ‘Americas’ and the Middle East Africa regional qualifier introduced for the They will be joined by three more European first time, in an exciting signal of the sport’s nations at the end of 2016, at which time the burgeoning geographical ambitions. -

Annual Report 2017

RUGBY LEAGUE EUROPEAN FEDERATION ANNUAL REPORT 2017 Canada closes out the Americas Championship vs USA in Toronto – September. Irish, German and Welsh match officials at the Cardiff L2 course - September A MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIR I have great pleasure in warmly welcoming you to the 2017 RLEF annual report. World cup years are always special occasions and the fifteenth edition of the Rugby League World Cup allowed us all to enjoy the colour, spectacle and growing competitiveness of the sport. Congratulations and commiserations to England, who so nearly defeated Australia in a tense final but who nevertheless played fantastically well throughout a tournament I was pleased to accept Nationaler Rugby that saw the southern hemisphere nations League Deutschland and Nederlandse Rugby excel. The future of international rugby League Bond to the membership, following league looks exceptionally bright with the the launch of the German BundesLeague and likes of Tonga and Fiji gradually gaining Dutch championship. They were joined by five ground on the traditional big three, and it is new Observers, in Bulgaria, Cameroon, incumbent upon RLEF nations to continue to Democratic Republic of Congo, Greece and grow and produce more and more players Turkey. It is now incumbent upon those who will broaden that path to elite, nations to follow Germany and Holland’s international rugby. example and become members. The RLEF Board, and our colleagues in Pleasingly, both Greece and Turkey are boardrooms throughout the membership, can already running club competitions, putting influence such performance pathways by them in strong positions at the beginning of ensuring they are part of well organised, their existence. -

Injury in Summer Rugby League Football: the Experiences of One Club

Br J Sports Med 1998;32:149–152 149 Injury in summer rugby league football: the Br J Sports Med: first published as 10.1136/bjsm.32.2.149 on 1 June 1998. Downloaded from experiences of one club C Gissane, D Jennings, J White, A Cumine Abstract elimination of two cup competitions. Injury Objective—To investigate whether the studies carried out in Australia135have consist- movement of the playing season from ently reported higher injury rates than English winter to summer would alter the risk of studies,24and it was surmised that this was due injury to players taking part in first team to the game being played on harder surfaces.4 European professional rugby league. Playing rugby league in the summer months Methods—The study design was a histori- may also increase the likelihood of players suf- cal cohort design comparing winter and fering from thermal injuries and heat stroke, as summer seasons in first team European the result of a combination of higher tempera- rugby league, which recorded injuries tures and relative humidities.6–8 received by players during match play. It is unusual for a sport to completely change Each injury was classified according to its playing calendar, and this move may result site, type, player position, activity at the in an alteration in the risk of injury to players. time of injury, and time oV as a result of Therefore the purpose of the present study was injury. to ascertain whether or not the movement of Results—The risk of injury when playing the playing season from the autumn and winter summer rugby league was higher than months to the spring and summer months when playing winter rugby league (relative would alter the risk of injury to players taking risk = 1.67 (95% confidence interval 1.18 to part in professional rugby league in the new 2.17)). -

Annual Report 2013

RUGBY LEAGUE EUROPEAN FEDERATION ANNUAL REPORT 2013 Rugby League European Federation 1 CONTENTS MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIR 3 RLEF PROFILE & VALUES 6 GENERAL MANAGER 7 COACHING MANAGER 10 MATCH OFFICIALS MANAGER 12 MEDIA MANAGER 14 Serbia takes on Russia in the GOVERNANCE 15 European Shield in Belgrade, Serbia - May STRATEGY 19 OFFICIAL COMPETITIONS 27 AFFILIATED COMPETITIONS 29 OTHER INTERNATIONALS 31 FINANCIAL REPORT 35 THE BOARD 39 APPENDIX1: ORGANISATION 41 APPENDIX 2: DOMESTIC CH. 42 French Federation staff delivering a Level One coaching course in Casablanca, Morocco - April Rugby League European Federation 2 A MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIR Two thousand and thirteen marked my first full year as chairman of the Rugby League European Federation, and it was my distinct pleasure to be in post during the year of the excellent Rugby League World Cup, which exceeded pre-tournament expectations in most categories and excited the passions of so many people. That excitement stemmed not only from the on-field action, but also the realisation that the sport is on the threshold of one of the most significant periods in its international history – a period in which the RLEF is positioned to play a major part. The RLEF’s fundamental role – to develop the sport in Europe and the surrounding territories that temporarily fall under our jurisdiction – has never been more important It is significant to note that, following than it is now, with rugby league keen to Lebanon and Serbia’s elevation in 2012, we broaden its global footprint while are now starting to see non-traditional rugby understanding the need to do so in a countries reaching this level of maturity for sustainable and efficient manner. -

New Odd Template

CYAN MAGENTA YELLOW BLACK P A Wild First baby G A Porch E Ways of 2009 in Egypt PAGE 8A PAGE 10A PAGE 5B 2 75¢ WEDNESDAY, January 7, 2009 / 22 PAGES, 3 SECTIONS • www.fbnewsleader.com Sellers, not buyers County gets new top prosecutor SHANNON MALCOM New Fourth News-Leader Judicial District State Attorney Local attorney Wesley White has Angela Corey been appointed director of the Nassau announced White’s County State Attorney’s Office. appointment at a He will replace Assistant State swearing-in ceremo- Attorney Stephen Bledsoe, who will ny Tuesday at the return to the Jacksonville office. Nassau County Bledsoe had replaced Granville “Doc” White Judicial Annex. Burgess after he won election as coun- Corey and new ty judge in 2006. Public Defender White, who has a law practice in Matthew Shirk both were sworn in Fernandina Beach and lives in Yulee, Tuesday, the first time that took place will become the county’s top prose- cuting attorney. WHITE Continued on 3A Willette to direct Council on Aging News-Leader “These are par- ticularly difficult RYAN SMITH/NEWS-LEADER The Council on Aging has appoint- times for non-profit Fred Lindes, above, owner and operator of Island Pawn, 1421 ed Kenneth J. Willette as executive organizations as the ‘Business is South 10th St., says not as many people are coming into his shop director of the agency. He replaces Al number of people in to buy these days due to the economic downturn. However, many Rizer, who left in October for a similar need is increasing people come in to sell or pawn their property.