F-MARC Football Medicine Manual 2Nd Edition F-MARC Football Medicine Manual 2Nd Edition 2 Editors - Authors - Contributors | Football Medicine Manual

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ENEL — Società Per Azioni (Incorporated with Limited Liability in Italy) U.S

OFFERING CIRCULAR NOT FOR GENERAL CIRCULATION IN THE UNITED STATES ENEL — Società per Azioni (incorporated with limited liability in Italy) U.S. $1,250,000,000 Capital Securities due 2073 Enel — Società per Azioni (the “Issuer” or “Enel”) will issue U.S. $1,250,000,000 Capital Securities due 2073 (the “Securities”) on September 24, 2013 (the “Issue Date”). The Securities will bear interest on their principal amount (a) from (and including) the Issue Date to (but excluding) the First Reset Date, at the rate of 8.750 percent per annum and (b) from (and including) the First Reset Date to (but excluding) the Maturity Date, for each Reset Period, the relevant 5-year Swap Rate plus (A) in respect of the Reset Periods commencing on the First Reset Date, September 24, 2028, September 24, 2033 and September 24, 2038, 6.130 percent per annum, and (B) in respect of any other Reset Period, 6.880 percent per annum (each, as defined in “Description of the Securities”). Interest on the Securities will be payable semi- annually in arrears on March 24 and September 24 each year, commencing on March 24, 2014 (each an “Interest Payment Date”). Payment of interest on the Securities may be deferred at the option of the Issuer in certain circumstances, as set out under “Description of the Securities — Interest Deferral”. The Securities will be issued in fully registered form and only in denominations of U.S. $200,000 and in integral multiples of U.S. $1,000 in excess thereof. Unless previously redeemed by the Issuer as provided below, the Issuer will redeem the Securities on September 24, 2073 at their principal amount, together with interest accrued to, but excluding, such date and any Arrears of Interest (as defined in “Description of the Securities”). -

I) Attention Is Drawn to the Fact That the Copyright of a Thesis Rests with Its Author. Requests for Such Permission Should Be A

For the attention of candidates who have completed Part A i) Attention is drawn to the fact that the copyright of a thesis rests with its author. ii) A copy of a candidate's thesis is supplied to the Library on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with its author and that no quotation from the thesis and no information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author or University, as' appropriate. Requests for such permission should be addressed in the first instance to the Head of Library Services. 4 The epidemiological approach to sports injury: the case for rugby league A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Conor Gissane Department of Health and Social Care, Brunel University May 2003 11 Abstract In any sporting activity it is important to know how many injuries players might receive and also what type of injuries will be received, so that efforts can be made to reduce the risk of injury. This thesis examines the injury incidence associated with playing professional rugby league, and examines some of the risks associated with injury whilst playing the game. The first paper describes the pattern of injury incidence in professional rugby league and noted that it is higher than in other popular team sports. The second paper examines the different exposures of forward and back players and observes that forwards experience higher rates of injury. The third and fourth papers examine the effect of moving the playing calendar to summer rugby. -

Movement Demands of Elite Rugby League Players During Australian National Rugby League and European Super League Matches

International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 2014, 9, 925-930 http://dx.doi.org/10.1123/ijspp.2013-0270 © 2014 Human Kinetics, Inc. www.IJSPP-Journal.com ORIGINAL INVESTIGATION Movement Demands of Elite Rugby League Players During Australian National Rugby League and European Super League Matches Craig Twist, Jamie Highton, Mark Waldron, Emma Edwards, Damien Austin, and Tim J. Gabbett Purpose: This study compared the movement demands of players competing in matches from the elite Australian and European rugby league competitions. Methods: Global positioning system devices were used to measure 192 performances of forwards, adjustables, and outside backs during National Rugby League (NRL; n = 88) and European Super League (SL; n = 104) matches. Total and relative distances covered overall and at low (0–3.5 m/s), moderate (3.6–5 m/s), and high (>5 m/s) speeds were measured alongside changes in movement variables across the early, middle, and late phases of the season. Results: The relative distance covered in SL matches (95.8 ± 18.6 m/min) was significantly greater (P < .05) than in NRL matches (90.2 ± 8.3 m/min). Relative low-speed activity (70.3 ± 4.9 m/min vs 75.5 ± 18.9 m/min) and moderate-speed running (12.5 ± 3.3 m m/min vs 14.2 ± 3.8 m/min) were highest (P < .05) in the SL matches, and relative high-speed distance was greater (P < .05) during NRL matches (7.8 ± 2.1 m/min vs 6.1 ± 1.7 m/min). Conclusions: NRL players have better maintenance of high-speed running between the first and second halves of matches and perform less low- and moderate-speed activity, indicating that the NRL provides a higher standard of rugby league competition than the SL. -

Topical Diagnosis in Neurology

V Preface In 2005 we publishedacomplete revision of Duus’ Although the book will be useful to advanced textbook of topical diagnosis in neurology,the first students, also physicians or neurobiologists inter- newedition since the death of its original author, estedinenriching their knowledge of neu- Professor PeterDuus, in 1994.Feedbackfromread- roanatomywith basic information in neurology,oR ers wasextremelypositive and the book wastrans- for revision of the basics of neuroanatomywill lated intonumerous languages, proving that the benefit even morefromit. conceptofthis book wasasuccessful one: combin- This book does notpretend to be atextbook of ing an integrated presentation of basic neu- clinical neurology.That would go beyond the scope roanatomywith the subject of neurological syn- of the book and also contradict the basic concept dromes, including modern imaging techniques. In described above.Firstand foremostwewant to de- this regard we thank our neuroradiology col- monstratehow,onthe basis of theoretical ana- leagues, and especiallyDr. Kueker,for providing us tomical knowledge and agood neurological exami- with images of very high quality. nation, it is possible to localize alesion in the In this fifthedition of “Duus,” we have preserved nervous system and come to adecision on further the remarkablyeffective didactic conceptofthe diagnostic steps. The cause of alesion is initially book,whichparticularly meets the needs of medi- irrelevant for the primarytopical diagnosis, and cal students. Modern medical curricula requirein- elucidation of the etiology takes place in asecond tegrative knowledge,and medical studentsshould stage. Our book contains acursoryoverviewofthe be taught howtoapplytheoretical knowledge in a major neurologicaldisorders, and it is notintended clinical settingand, on the other hand, to recognize to replace the systematic and comprehensive clinical symptoms by delving intotheir basic coverage offeredbystandardneurological text- knowledge of neuroanatomyand neurophysiology. -

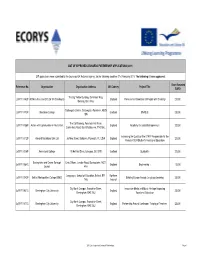

2011 List of Approved Leonardo Partnerships Page 1 Grant Awarded Reference No

LIST OF APPROVED LEONARDO PARTNERSHIP APPLICATIONS (2011) 217 applications were submitted to the Leonardo UK National Agency, for the following deadline: 21st February 2011. The following 81 were approved: Grant Awarded Reference No. Organisation Organisation Address UK Country Project Title EURO The Big Yellow Building, 25 Alfreds Way, LdVP/11/182P 3D Ministries and CO Ltd T/A Streetwyze England Professional Orientation of People with Disability 20,000 Barking, IG11 0AG Gallowgate Centre, Gallowgate, Aberdeen, AB25 LdVP/11/173P Aberdeen College Scotland ENABLE 25,000 1BN The Old Granary, Penstock Hall Farm, LdVP/11/158P Action with Communities in Rural Kent England Academy for Social Entrepreneurs 20,000 Canterbury Road, East Bradbourne, TN2 55LL Increasing the Quality of the STAFF Responsible for the LdVP/11/112P Almond Vocational Link Ltd 36 New Street, Barbican, Plymouth, PL1 2NA England 20,000 Period of SEN Student's Vocational Education LdVP/11/006P Anniesland College 19 Hatfield Drive, Glasgow, G12 0YE Scotland Qualipaths 20,000 Basingstoke and Deane Borough Civic Offices, London Road, Basingstoke, RG21 LdVP/11/084C England Engineering + 15,000 Council 4AH Languages, School of Education, Belfast, BT1 Northern LdVP/11/042P Belfast Metropolitan College (BMC) Building Europe through Language Learning 25,000 1HS Ireland City North Campus, Franchise Street, Innovative Media and Music Heritage Impacting LdVP/11/031C Birmingham City University England 25,000 Birmingham, B42 2SU Vocational Education City North Campus, Franchise Street, LdVP/11/077C Birmingham City University England Partnership Around Continuous Training of Teachers 25,000 Birmingham, B42 2SU 2011 List of approved Leonardo Partnerships Page 1 Grant Awarded Reference No. -

Disorders of the Contractile Structures 54

Disorders of the contractile structures 54 CHAPTER CONTENTS and is felt as a sudden, painful ‘giving way’ at the front of the Extensor mechanism 713 thigh. Alternatively, the muscular lesion may result from a direct contusion during contact sports (judo or American foot- Quadriceps strains and contusions . 713 ball), known as ‘Charley Horse’. Adherent vastus intermedius . 714 Patients who suffer an acute quadriceps strain will usually Tendinous lesions about the patella . 714 know right away. They are typically involved in sports requiring Rupture of the quadriceps tendon . 718 kicking, jumping, or initiating a sudden change in direction while running. Frequently, a sharp pain is felt, associated with Lesions of the infrapatellar tendon . 718 a loss in function of the quadriceps. Sometimes pain will not Lesions of the insertion at the tibial tuberosity . 719 fully develop during the athlete’s activity while the thigh is Patellar fracture . 719 warm; consequently, the extent of the injury is underesti- Patellofemoral disorders 719 mated. Stiffness, disability and pain then set in some time Introduction . 719 afterwards, e.g. late at night, and the following morning the patient can walk only with a limp.1 Mechanical theory . 719 Clinical examination shows a normal hip and knee, although Neural theory . 720 passive knee flexion is painful or both painful and limited, Clinical examination . 720 depending on the size of the rupture. Resisted extension of the Clinical manifestations . 722 knee is painful and slightly weak. As a rule, the lesion is in the 2 Strained iliotibial band 724 rectus femoris, usually at mid-thigh level. The affected muscle belly is hard and tender over a large area. -

Porro NEWORK NEWS

International Polio Network SAINT LOUIS, MISSOURIUSA Winter 2003 .Vol. 19, No. 1 Porro NEWORKNEWS Straight Answers to Your "Cramped" Questions Holly H. Wise, P7; PhD, and Kerri A. Kolehma, MS, MD, Coastal Post-Polio Clinic, Charleston, South Carolina Tired in the morning? Is it diffi- Cramps can occur throughout origins anywhere in the central cult to get comfortable for a good the day but more often occur at and peripheral nervous systems night of sleep? A complaint often night or when a person is resting. and may explain the wide range reported at the Coastal Post-Polio Although it is not known exactly of conditions in which the Clinic in Charleston, South why cramps happen mostly at cramping occurs (Bentley, 1996). Carolina, is the inability to get these times, it is thought that to sleep at night due to leg pain, the resting muscle is not being Seeking Answers twitching, or cramping. stretched and is therefore more A thorough history and possibly easily excited. Muscle cramping is a relatively a referral for screening labs will common, painful, and bother- The basis for the theory that help determine the causes for some complaint among generally I cramps occur more at rest, due to I leg pain and cramping. Polio healthy adults, and is more com- I the muscle not being stretched, I survivors can provide a descrip- mon in women than men. Some I is that passive stretching can I tion of their muscle cramps, studies estimate as many as 50- 1 relieve muscle cramping. Pain I identification of the time and 70% of older adults may experi- I associated with cramping is likely I place when they occur, and an ence nocturnal leg and foot I caused by the demand of the I activity log of the 24-48 hours cramps (Abdulla, et. -

Muscle Spasms and Strains

MUSCULOSKELETAL HEALTH Muscle spasms may have many possible causes, including, Muscle spasms but not limited to: • Poor blood circulation and strains • Overexertion of the muscles while exercising • Insufficient stretching before exercise • Excessive exercise in the heat Lynn Lambert, BPharm • Muscle fatigue Amayeza Info Centre • Dehydration • A magnesium and/or potassium deficiency • A side-effect of medication. Introduction A muscle locked in spasm produces a sudden, tight and Muscles are the “powerhouse” of the human body as their main intense pain. The pain can range in intensity from slight to agonising. A muscle in spasm may feel hard to the touch, function is to produce motion. Skeletal muscle is responsible and/or appear visibly distorted. A twitch beneath the skin can for the movement of external areas of the body, for example, be seen in some cases. A spasm can last a few seconds to the limbs. Most people experience a muscular injury, such as a 15 minutes or longer, and may recur a few times before it goes spasm or a strain, at some time during their lives. Such injuries away. can occur during sport or exercise, but can also take place while sitting, walking, or even during sleep. Muscle spasms Treatment and prevention and strains are a common complaint with which patients Muscle spasms usually resolve with self-care measures present at a pharmacy. Therefore, the pharmacist’s assistant without the need to see a doctor. It is important that the patient is in an ideal position to provide practical advice, combined stops the activity which triggered the spasm. -

Una Voce JOURNAL of the PAPUA NEW GUINEA ASSOCIATION of AUSTRALIA INC (Formerly the Retired Officers Association of Papua New Guinea Inc)

ISSN 1442-6161, PPA 224987/00025 2005, No 2 - June Una Voce JOURNAL OF THE PAPUA NEW GUINEA ASSOCIATION OF AUSTRALIA INC (formerly the Retired Officers Association of Papua New Guinea Inc) Patrons: His Excellency Major General Michael Jeffery AC CVO MC (Retd) Governor-General of the Commonwealth of Australia Mrs Roma Bates; Mr Fred Kaad OBE In This Issue CHRISTMAS LUNCHEON – IN 100 WORDS OR LESS 3 This year’s Christmas Luncheon will WALK INTO PARADISE 4 be on Sunday 4 December at the NEWS FROM THE NORTHERN TERRITORY 5 Mandarin Club Sydney. We will have NEWS FROM SOUTH AUSTRALIA 6 a special theme to celebrate 30 years since PNG Independence. Look in the PNG......IN THE NEWS 7 September issue of Una Voce for Rick Nehmy reports 9 details...you will need to book early! More About Tsunami And Earthquakes 11 DONATION OF TIMBER TO MANAM ISLANDERS 14 * * * MADANG HONOURS WAR DEAD 14 VISIT TO THE MOUNTAINS EDUCATIONAL LEADERSHIP 15 The annual spring visit to the Blue MARITIME COLLEGE ACQUIRES STOREHOUSES Mountains will be on Thursday 13 15 October, 2005. Last year we were again KIAPHAT OF PORONPOSOM 16 welcomed at the spacious home of COX AND THE WENZELS 19 George and Edna Oakes at Woodford for THE SOUTH PACIFIC GAMES 20 another warm and friendly gathering. WANPELA MO BLADI ROT NA PINIS OLGERA 22 Fortunately Edna and George will be our Agricultural Development in PNG 24 hosts again this year. Full details in KOKODA TRACK AUTHORITY 26 September issue. REUNIONS 27 * * * Help Wanted 28 CPI: The CPI for our superannuation PNGAA COLLECTION - FRYER LIBRARY 29 rose 1.4% for the six months to March BOOK NEWS AND REVIEWS 30 2005 and will be paid at the end of The Lost Garrison of Rabaul 32 June. -

A Patient's Guide to Muscle Cramps Or Striated Muscles Are Those That We Move by Choice (For Example, the Muscles in Your Arms and Legs)

A Patient’s Guide to Muscle Cramps The Central Orthopedic Group 651 Old Country Road Plainview, NY 11803 Phone: 5166818822 Fax: 5166813332 [email protected] Compliments of: The Central Orthopedic Group DISCLAIMER: The information in this booklet is compiled from a variety of sources. It may not be complete or timely. It does not cover all diseases, physical conditions, ailmentsA orPatient's treatments. The Guide information to should Muscle NOT be usedCramps in place of a visit with your health care provider, nor should you disregard the advice of your health care provider because of any information you read in this booklet. The Central Orthopedic Group The Central Orthopedic Group 651 Old Country Road Plainview, NY 11803 Phone: 5166818822 Fax: 5166813332 [email protected] http://thecentralorthopedicgroup.com All materials within these pages are the sole property of Medical Multimedia Group, LLC and are used herein by permission. eOrthopod is a registered trademark of Medical Multimedia Group, LLC. 2 Compliments of: The Central Orthopedic Group A Patient's Guide to Muscle Cramps or striated muscles are those that we move by choice (for example, the muscles in your arms and legs). These muscles are attached to bones by tendons, a sinewy type of tissue. Involuntary muscles, or smooth muscles, are the ones that move on their own (for example, the muscles that control your diaphragm and help you breathe). The muscles in your heart are called involuntary cardiac muscles. Introduction You have over 600 muscles in your body. These muscles control everything you do, from breathing to putting food in your mouth to swallowing. -

(Application Reference: EAC/18/2011/026) AGREEMENT

(Application reference: EAC/18/2011/026) AGREEMENT EAC-2011-xxxx ANNEX I DESCRIPTION OF THE ACTION Title of the Project: European Rugby League Governance Foundation Project Beneficiary: European Rugby European Federation Partners: Česká Asociace Rugby League Rugby League Deutschland Federazione Italiana Rugby League Latvijas Regbija Ligas Federacija Nederland Rugby League Bond Svensk Rugby League Förening Rugby Football League Fédération Française de Rugby à XIII Wales Rugby League Scotland Rugby League Rugby League Ireland Summary of the project objectives and activities: CONTEXT Since the adoption of its new constitution and eight-year strategy [both promulgated in August 2010] the RLEF is committed to disseminate best practice in the area of governance throughout its Membership, many of whom are inexperienced NGBs to whom the importance of good governance may not be immediately obvious. MAIN OBJECTIVES To address this, the Governance Foundation Project [GFP] has created a tiered Membership structure of the RLEF – Bronze [Observer status], Silver [Affiliate Member], Gold [Full Member] – where best practice and the principles of good governance will be promoted, and the cooperation between partners will develop the European dimension throughout rugby league, itself a young sport on the Continent, [foundation date of January 2003]. Use of Mentors and Learners provides innovation. ACTIVITIES In addition to utilising the Mentor-Learner system inherent in the GFP throughout a series of transnational exchanges, the project will utilise partnerships with more established European sports, namely football, to explore and cultivate good governance, using a series of seminars, technical visits and on-line tutorials and resources such as e-learning. RESULTS The objectives of the GFP are in line with the RLEF strategy, strengthening capacity building throughout and specifically elevating Learners from Bronze to Gold by project completion. -

Muscle Cramps Reliable and Validated Outcome Measures and New Treatments Are Needed

NEUROMUSCULAR DISORDERS Muscle Cramps Reliable and validated outcome measures and new treatments are needed. By Hans D. Katzberg, MD, MSc, FRCPC and Hamid Sadeghian, MD, FRCPC What Is a Muscle Cramp? limb syndromes) and peripheral processes, including tetany, A muscle cramp is a hyperexcit- myokymia, myotonia, neuromyotonia (focal muscle stiff- able neurologic phenomena of ness), or myalgia.6 excessive, involuntary muscle The origin and propagation of neurogenic muscle cramps contractions.1,2 It is important localizes to peripheral and central targets (Figure 1), including to distinguish between myogen- the neuromuscular junction, where mechanical disruption ic and neurogenic muscle cramps, because each has unique and electrolyte disturbances can influence hyperexcitability pathophysiology and management.3 The conventional defi- and cramp generation. Injury to peripheral nerve components nition of a muscle cramp is a painful contraction of a muscle including the motor neuron cell bodies or the motor axons or muscle group, relieved by contraction of antagonist can result in ephaptic transmission and development of mus- muscles.4 Colloquially, muscle cramps are known by a num- cle cramps. Dysfunctional intramuscular small fiber sensory ber of different terms depending on the country, including afferents (eg, mechanoreceptors and spindles) are also pro- charley horse in the US, chopper in England, and corky in posed to be involved in cramp generation.7-10 Centrally, persis- Australia.5 Care must be taken to avoid confusing muscle tent inward currents mediated by GABAergic transmitters at cramps with other phenomena including central hyperexcit- the spinal level can amplify incoming sensory input and lead ability (eg, dystonia, spasticity, seizures, and stiff person/stiff to the propagation and amplification of cramp potentials.11 Figure 1: Pathophysiology Underlying Neurogenic Muscle Cramps.