JOURNAL of EURASIAN STUDIES Volume IV., Issue 4

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Commissioning of Artwork for Charterhouses During the Middle Ages

Geography and circulation of artistic models The Commissioning of Artwork for Charterhouses during the Middle Ages Cristina DAGALITA ABSTRACT In 1084, Bruno of Cologne established the Grande Chartreuse in the Alps, a monastery promoting hermitic solitude. Other charterhouses were founded beginning in the twelfth century. Over time, this community distinguished itself through the ideal purity of its contemplative life. Kings, princes, bishops, and popes built charterhouses in a number of European countries. As a result, and in contradiction with their initial calling, Carthusians drew closer to cities and began to welcome within their monasteries many works of art, which present similarities that constitute the identity of Carthusians across borders. Jean de Marville and Claus Sluter, Portal of the Chartreuse de Champmol monastery church, 1386-1401 The founding of the Grande Chartreuse in 1084 near Grenoble took place within a context of monastic reform, marked by a return to more strict observance. Bruno, a former teacher at the cathedral school of Reims, instilled a new way of life there, which was original in that it tempered hermitic existence with moments of collective celebration. Monks lived there in silence, withdrawn in cells arranged around a large cloister. A second, smaller cloister connected conventual buildings, the church, refectory, and chapter room. In the early twelfth century, many communities of monks asked to follow the customs of the Carthusians, and a monastic order was established in 1155. The Carthusians, whose calling is to devote themselves to contemplative exercises based on reading, meditation, and prayer, in an effort to draw as close to the divine world as possible, quickly aroused the interest of monarchs. -

Johan Maelwael

Johan Maelwael 34 l COLLECT Een Nijmegenaar in Bourgondië In 2005 werd in Museum Valkhof de vroege Nederlandse schilderkunst geëerd met linkerpagina Johan Maelwael & Henry Bellechose, een tentoonstelling over de gebroeders Van Limburg. De meest meeslepende anek- ‘Madonna met Kind engelen en vlinders’, Dijon, ca.1415, Berlijn, Ge- dote over hen is dat twee van de drie broers in november 1399 door Brabantse mi- mäldegalerie. litanten werden gegijzeld in Brussel. De tieners werden na een gevangenschap van meer dan een half jaar vrijgelaten omdat Filips de Stoute, de hertog van Bourgondië, het losgeld voor de jongens betaalde. Dit deed hij omdat hun oom zeer verdienstelijk werk voor hem had verricht en dat in de toekomst zou blijven doen. Deze geprezen oom was Johan Maelwael (ca. 1370-1415). Dit najaar organiseert het Rijksmuseum de eerste tentoonstelling die draait om deze schilder. TEKST: JOCHEM VAN EIJSDEN aelwael werd geboren rond 1370 in Nij- megen als telg van een van de meest Als leider van het atelier hoefde Maelwael zich niet Mvermaarde schildersfamilies in de Noor- delijke Nederlanden. De familienaam is in het alleen bezig te houden met de daadwerkelijke uitvoering Middelnederlands een blijk van waardering voor hun professionele kunde: ‘hij die goed schildert’, van de kunstobjecten in het kartuizerklooster. een uiting die ook werd onderschreven door het hertogelijke hof van Gelre. Nadat vader Willem Maelwael en oom Herman schilderwerk voor de Zo inspecteerde hij samen met zijn beeldhouwende stad Nijmegen hadden uitgevoerd, werkten zij van Hollandse evenknie Claus Sluter ook de stukken 1386 tot 1397 een behoorlijk aantal keer voor de die door andere kunstenaars werden aangeleverd, hertog van Gelre. -

14 CH14 P468-503.Qxp 9/10/09 11:40 Page 468 14 CH14 P468-503.Qxp 9/10/09 11:40 Page 469 CHAPTER 14 Artistic Innovations in Fifteenth-Century Northern Europe

14_CH14_P468-503.qxp 9/10/09 11:40 Page 468 14_CH14_P468-503.qxp 9/10/09 11:40 Page 469 CHAPTER 14 Artistic Innovations in Fifteenth-Century Northern Europe HE GREAT CATHEDRALS OF EUROPE’S GOTHIC ERA—THE PRODUCTS of collaboration among church officials, rulers, and the laity—were mostly completed by 1400. As monuments of Christian faith, they T exemplify the medieval outlook. But cathedrals are also monuments of cities, where major social and economic changes would set the stage for the modern world. As the fourteenth century came to an end, the were emboldened to seek more autonomy from the traditional medieval agrarian economy was giving way to an economy based aristocracy, who sought to maintain the feudal status quo. on manufacturing and trade, activities that took place in urban Two of the most far-reaching changes concerned increased centers. A social shift accompanied this economic change. Many literacy and changes in religious expression. In the fourteenth city dwellers belonged to the middle classes, whose upper ranks century, the pope left Rome for Avignon, France, where his enjoyed literacy, leisure, and disposable income. With these successors resided until 1378. On the papacy’s return to Rome, advantages, the middle classes gained greater social and cultural however, a faction remained in France and elected their own pope. influence than they had wielded in the Middle Ages, when the This created a schism in the Church that only ended in 1417. But clergy and aristocracy had dominated. This transformation had a the damage to the integrity of the papacy had already been done. -

PDF Hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen

PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen The following full text is a publisher's version. For additional information about this publication click this link. http://hdl.handle.net/2066/105227 Please be advised that this information was generated on 2017-12-06 and may be subject to change. M e d ia e v a l p a in t in g in t h e N e t h e r l a n d s In the first decade of the fifteenth century, somewhere in the South Netherlands, the Apocalypse (Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, néerlandais 3) was written in Dutch (dietsche) and illuminated. No- one knows with any certainty exactly where this happened. Erwin Panofsky in his famous Early Netherlan dish Painting (1953) argued convincingly for Liège,· later Maurits Smeyers (1993) claimed it for Bruges (and did so again in his standard work Vlaamse Miniaturen (1998)). The manuscript cannot possibly have been written and illuminated in Liège, nor is it certain that it comes from Bruges (as convincingly demonstrat ed by De Hommel-Steenbakkers, 2001 ). Based on a detailed analysis of the language and traces of dialect in the Dutch text of the Apocalypse, Nelly de Hommel-Steenbakkers concluded that the manuscript originated in Flanders, or perhaps in Brabant. It might well have come from Bruges though, a flourishing town in the field of commerce and culture, but other places, such as Ghent, Ypres, Tournai and maybe Brussels, cannot be ruled out,· other possible candidates are the intellectual and cultural centres in the larger abbeys. -

Conclusion: the Entombments in the Context of Late Medieval Sculpture

Conclusion 149 Chapter 5 Conclusion: The Entombments in the Context of Late Medieval Sculpture The Future Forecast: Art from the Court of Philip the Bold While historians debate the waning of the Middle Ages, and whether the changes that occurred in medieval society c. 1500 were the result of a decline in the vitality of the culture, a socio-economic crisis, or a gradual transition to the early modern period, our query is decidedly more narrow in focus.1 Why did the sculptural representation of the Entombment of Christ have such a rela- tively short lifespan in the visual legacy of late medieval piety? The monumen- tal sculptures begin to appear in the first quarter of the fifteenth century, and, by the end of the sixteenth century, they simply had gone out of fashion. The Passion of Christ remained central to the Christian experience, yet the En- tombment as a vehicle of faith no longer seemed to answer the religious call to arms. Was there a change in liturgy that engendered this paradigm shift or sim- ply a new taste for the ornate, intricate worlds created in the Passion retables that proliferated during the late Middle Ages? This chapter will examine some of the sculpture that was produced in the regions of Burgundy and Champagne during and after the period in which the Entombments flourished and offer some final observations about the signifi- cance of the latter in their historical context. It is curious that the taste for statues of individual saints did not wane, nor did the Pietà lose any of its popu- lar appeal. -

The Friedsam Annunciation and the Problem of the Ghent Altarpiece Author(S): Erwin Panofsky Reviewed Work(S): Source: the Art Bulletin, Vol

The Friedsam Annunciation and the Problem of the Ghent Altarpiece Author(s): Erwin Panofsky Reviewed work(s): Source: The Art Bulletin, Vol. 17, No. 4 (Dec., 1935), pp. 432-473 Published by: College Art Association Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3045596 . Accessed: 14/06/2012 19:48 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. College Art Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Art Bulletin. http://www.jstor.org THE FRIEDSAM ANNUNCIATIONAND THE PROBLEMOF THE GHENT ALTARPIECE By ERWIN PANOFSKY N 1932 the collection of Early Flemish paintings in the Metropolitan Museum of New York was enriched by a fine and rather enigmatical Annunciation acquired and formerly owned by Col. Michael Friedsam (Fig. I). It has been tentatively attributed to Petrus Cristus, with the reservation, however, that it is "almost a van Eyck."1 To the attribution to Petrus Cristus there are several objections. The Friedsam painting does not show the technical characteristics of the other works by this master (the handling of the medium being "more archaic," as I learn from an eminent American X-ray expert,2 nor does it fit into his artistic development. -

'Touch the Truth'?: Desiderio Da Settignano, Renaissance Relief And

Wright, AJ; (2012) 'Touch the Truth'? Desiderio da Settignano, Renaissance relief and the body of Christ. Sculpture Journal, 21 (1) pp. 7-25. 10.3828/sj.2012.2. Downloaded from UCL Discovery: http://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/1356576/. ARTICLE ‘Touch the truth’?: Desiderio da Settignano, Renaissance relief and the body of Christ Alison Wright School of Arts and Social Sciences, University College London From the late nineteenth century, relief sculpture has been taken as a locus classicus for understanding new engagements with spatial and volumetric effects in the art of fifteenth- century Florence, with Ghiberti usually taking the Academy award for the second set of Baptistery doors.1 The art historical field has traditionally been dominated by German scholarship both in artist-centred studies and in the discussion of the so-called ‘malerischens Relief’.2 An alternative tradition, likewise originating in the nineteenth-century, has been claimed by English aesthetics where relief has offered a place of poetic meditation and insight. John Ruskin memorably championed the chromatic possibilities of low relief architectural carving in The Stones of Venice (early 1850s) and in his 1872 essay on Luca della Robbia Walter Pater mused on how ‘resistant’ sculpture could become a vehicle of expression.3 For Adrian Stokes (1934) the very low relief figures by Agostino di Duccio at the Tempio Malatestiano in Rimini represented a vital ‘blooming’ of luminous limestone.4 Stokes’ insistence that sculptural values were not reducible to modelling, which he identified -

Les Tombeaux Des Ducs De Bourgogne, Au Cœur De Leur Palais

Les tombeaux des ducs de Bourgogne, au cœur de leur palais Les tombeaux de Philippe le Hardi et de Jean sans Peur proviennent de la chartreuse de Champmol. Magnifiquement restaurés après les vicissitudes de la Révolution française et installés en 1827 dans la grande salle du palais, ils sont le passage incontournable de toute visite de Dijon. Ils comptent parmi les plus magnifiques monuments funéraires de la fin du Moyen-Âge. L’exceptionnel cortège de pleurants enveloppés dans des manteaux aux généreux drapés porte le deuil éternel du prince, et exprime toute la variété des sentiments d’affliction et d’espoir. A l’occasion des travaux de rénovation du musée, les pleurants du tombeau de Jean sans Peur sont de 2010 à 2012 les ambassadeurs du musée et de la Bourgogne aux Etats-Unis, au Metropolitan Museum de New York puis à Saint Louis, Dallas, Minneapolis, Los Angeles, San Francisco et Richmond, puis au musée de Cluny, musée national du Moyen-Âge à Paris. Les tombeaux p. 2-3 Les pleurants p. 4-5 Les retables p. 6-7 La chartreuse de Champmol p. 8-9 La salle des tombeaux p. 10-11 A voir, à lire, sur le web p. 12 Les tombeaux de Philippe le Hardi et de Jean sans Peur 1 Fig. 1. Vue de la salle des tombeaux. Dans le cadre impressionnant de la grande (fig. 3) et le lion étaient encore à sculpter. Les tombeaux viennent de la chartreuse de salle du palais des ducs (fig.1), leurs C’est à Claus de Werve que le duc Jean Champmol. -

Dr Cristina Dondi Was Awarded the Italian OSI

1 The objects and aims of the Consortium of European Research Libraries (CERL) are to provide services to its members and to the library and scholarly world at large in the form of bibliographical databases, seminars, workshops, publications and co- operation with other library organisations and individual libraries and their staff. CERL concentrates its efforts on printed material from the hand-press period – up to the first half of the 19th century – and on manuscripts, in analogue or digital format. Content Honour for CERL Secretary … 1 Early Modern Book Project ....7 CERL Meetings, Amsterdam October 2017 … 2 IFLA Call for Papers ....7 CERL Committees in 2018 … 3 Opening up the Onassis Library ....8 CERL Annual General Meeting, Venice 2018 … 4 First Security Network Summer School ....9 Customising your ISTC search screen … 4 15cHEBRAICA ....9 New sources for Book History Conference … 5 20th Fiesole Retreat in Barcelona ....10 International Standard Number for Manuscripts… 6 Collaborating with Arkyves ....10 News of collaboration with LIBER ....11 Dr Cristina Dondi was awarded the Italian OSI Cristina Dondi, was conferred the honour of ‘Cavaliere’ of the Order of ‘Stella d’Italia’ (OSI) by His Excellency the Ambassador of Italy, Pasquale Terracciano, on behalf of the President of Italy, during a ceremony at the Ambassador’s residence in London on 4 December 2017. Dr Dondi, Oakeshott Senior Research Fellow at Lincoln College Oxford and Secretary of CERL, received the honour for her work on the European printing revolution and in support of European and American libraries. Dr Dondi’s speech, and an article on the 15cBOOKTRADE Project in the Italian national press, Il Corriere della Sera on 4 December 2017, can be read here. -

Sculpture, Polychromy, and Architectural Decoration Polychrome Sculpture: Decorative Practice and Artistic Tradition Tomar, May 28-29 2013

ICOM-CC Working Group: Sculpture, Polychromy, and Architectural Decoration Polychrome Sculpture: Decorative Practice and Artistic Tradition Tomar, May 28-29 2013 Papers Geopolymers: potential use in sculpture restoration. João Coroado Email: [email protected] Departmental Unit of Archaeology, Conservation and Restoration and Heritage/GEOBIOTEC & Polytechnic Institute of Tomar, Quinta do Contador - Estrada da Serra 2300-313, Tomar, Portugal. The ‘alkali activated’ or ‘geopolymers’ have been studied since 1950s and, until now, many applications have been tested with success and advantages compared with traditional applications. In the scope of conservation of terracotta sculpture some advances have also been reported. Geopolymers are formed by partial dissolution of alumino-silicate powders, often characterised by a high degree of amorphous phase and subsequent repolymerisation. At a relative low temperature, the rising chains of an alkali-aluminosilicate gel phase finish by hardening of a mainly amorphous three-dimensional net with bonded inclusions of unreacted solid precursor particles. Much of the interest in the study of this group of materials is the high possibility of using different raw-materials that enable the formations of geopolymers. In this context, the approach covers firstly a short history of geopolymer science, secondly the chemistry that is involved in the geopolymerisation process and the raw materials characteristics, and finally the properties and applications of geopolymers, with special attention to the potential applications in the conservation of terracotta sculpture. Polychrome coatings on a lime plaster altarpiece (1571): the Gaspar Fragoso chapel in Portalegre. Patrícia Alexandra Rodrigues Monteiro Email: [email protected] PhD Candidate, Researcher of the Art History Institute of the Faculty of Letters of the Lisbon University, R. -

Dijon, Burgundy Elizaveta Strakhov Marquette University, [email protected]

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette English Faculty Research and Publications English, Department of 1-1-2016 Dijon, Burgundy Elizaveta Strakhov Marquette University, [email protected] Jean-Pascal Pouzet Published version. "Dijon, Burgundy," in Europe: A Literary History, 1348-1418, Volume 1. Ed. David Wallace. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016: 102-124. Publisher link. © 2016 Oxford University Press. Used with permission. Chapter 6 Dijon, Burgundy ELIZAVETA STRAKHOV, WITH JEAN-PASCAL POUZET IN early August 1349, returning to England from Avignon as the newly consecrated archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Bradwardine passed through Burgundy and called at Dijon. Just over three weeks later, on 26 August, back in London, the distinguished theologian died of the plague. He had become infected precisely in Dijon, since the pandemic had reached Chcllon-sur-Saone and Dijon by early August 1349. 1 This anecdote perhaps too neatly exemplifies Dijon's role in our period: a moderately populated, 'second-rank' city on an important road, worthy of an English archbishop's halt, exerting strong local influence while producing significant repercussions elsewhere in Europe. At first sight, there seems little to recommend the traditional capital of the duchy of Burgundy for a specifically literary history between 1348 and 1418, the period immediately predating the glorious efflorescence of arts and belles-lettres at the courts of the later Valois Burgundian dukes, Philip the Good (r. 1419-67) and Charles the Bold (r. 1467-77) . Compared to other places in our volume, Dijon might be considered a sort of'absent city', lacking eminent figures who, like Machaut at Reims, might emblematize their native or adopted place. -

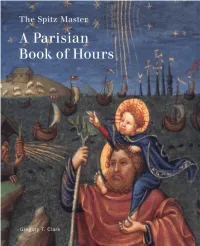

The Spitz Master: a Parisian Book of Hours

The Spitz Master A Parisian Book of Hours The Spitz Master A Parisian Book of Hours Gregory T. Clark GETTY MUSEUM STUDIES ON ART Los Angeles For Nicole Reynaud and François Avril © 2003 J. Paul Getty Trust Cover: Spitz Master (French, act. ca. 1415-25). Saint Getty Publications Christopher Carrying the Christ Child [detail]. 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 500 Spitz Hours, Paris, ca. 1420. Tempera, gold, Los Angeles, California 90049-1682 and ink on parchment bound between www.getty.edu pasteboard covered with red silk velvet, 247 leaves, 20.3 x 14.8 cm (715/ie x 5% in.). Christopher Hudson, Publisher Los Angeles, J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 57, Mark Greenberg, Editor in Chief 94.ML.26, fol. 42V (see Figure 7). Mollie Holtman and Tobi Kaplan, Editors Frontispiece: Diane Mark-Walker, Copy Editor Spitz Master, The Virgin and Child Jeffrey Cohen, Series Designer Enthroned [detail]. Spitz Hours, fol. 33V Suzanne Watson, Production Coordinator (see Figure 6). Christopher Foster, Photographer Typeset by G&S Typesetters, Inc., The books of the Bible are cited according Austin, Texas to their designations in the Douay-Rheims Printed in Hong Kong by Imago version translated from the Latin Vulgate. Library of Congress Full-page illustrations from the Spitz Hours Cataloging-in-Publication Data are reproduced at actual size. Clark, Gregory T., 1951- All photographs are copyrighted by the The Spitz master : a Parisian book of issuing institutions, unless otherwise noted. hours / Gregory T. Clark. p. cm. — (Getty Museum studies on art) Includes bibliographic references. ISBN 0-89236-712-1 i. Spitz hours—Illustrations.