History of Macedonia EN V6

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Detailed Fact Sheet 19.Pdf

THE RESORT Imagine overlooking the azure sea sparkling from every angle you stand. Imagine sinking your toes in the warm sand, feeling carefree, and free to self-care. Even so, there are places that cannot be fully framed in our imagination. It is only the soul that can genuinely recognize their blessings emerging from their land, their skyline and the smile of their people. Miraggio Thermal Spa Resort is one of them, a luxury spa resort in Halkidiki; a Greek Eden of unpretentious comfort lying amphitheatrically at the tip of the Kassandra peninsula, an ideal destination for families. This seafront enclave of well being and countless amenities descends on a lovely hill slope across 330 acres at one of the most unspoiled and least exploited areas in North Greece. Location The region is situated at the northern Aegean sea and shaped like a three-fingers palm; Kassandra, Sithonia and Mount Athos are the names of its peninsulas and each one of them has something unique to offer. Due to its easy access from different parts of Europe and Thessaloniki, and thanks to its recognized and contemporary hospitality infrastructure, Halkidiki is one of the ideal locations for holidays, international conferences, incentives and cruises. Weather 280 sunny days per year; mild Mediterranean microclimate. Neighborhood & Access Miraggio Thermal Spa Resort abstains from Thessaloniki airport 120 km. The second largest city of Greece is charming, ancient and vibrant, lies on the shore of the Thermaic Gulf and welcomes warmly its visitors. 63085 Paliouri, Kanistro,Halkidiki GR Reservations: [email protected] T: +30 2374440 000 E: [email protected] F: +30 23744 40 001 W: www.miraggio.gr Dining & Bars At Miraggio Thermal Spa Resort, a marvelous array of kitchen venues, food services, and bars is offered. -

Agricultural Practices in Ancient Macedonia from the Neolithic to the Roman Period

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by International Hellenic University: IHU Open Access Repository Agricultural practices in ancient Macedonia from the Neolithic to the Roman period Evangelos Kamanatzis SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Arts (MA) in Black Sea and Eastern Mediterranean Studies January 2018 Thessaloniki – Greece Student Name: Evangelos Kamanatzis SID: 2201150001 Supervisor: Prof. Manolis Manoledakis I hereby declare that the work submitted is mine and that where I have made use of another’s work, I have attributed the source(s) according to the Regulations set in the Student’s Handbook. January 2018 Thessaloniki - Greece Abstract This dissertation was written as part of the MA in Black Sea and Eastern Mediterranean Studies at the International Hellenic University. The aim of this dissertation is to collect as much information as possible on agricultural practices in Macedonia from prehistory to Roman times and examine them within their social and cultural context. Chapter 1 will offer a general introduction to the aims and methodology of this thesis. This chapter will also provide information on the geography, climate and natural resources of ancient Macedonia from prehistoric times. We will them continue with a concise social and cultural history of Macedonia from prehistory to the Roman conquest. This is important in order to achieve a good understanding of all these social and cultural processes that are directly or indirectly related with the exploitation of land and agriculture in Macedonia through time. In chapter 2, we are going to look briefly into the origins of agriculture in Macedonia and then explore the most important types of agricultural products (i.e. -

Fisheries in Greece

EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT NOTE Directorate-General for Internal Policies of the Union Policy Department Structural and Cohesion Policies FISHERIES IN GREECE FISHERIES 11/04/2006 EN Directorate-General for Internal Policies of the Union Policy Department: Structural and Cohesion Policies FISHERIES FISHERIES IN GREECE NOTE Content: Document describing the fisheries sector in Greece for the Delegation of the Committee on Fisheries to Thessaloniki (3 to 6 June 2006). IPOL/B/PECH/NT/2006_02 11/04/2006 PE 369.028 EN This note was requested by the European Parliament’s Committee on Fisheries. This document has been published in the following languages: - Original: ES; - Translations: DE, EL, EN, IT. Author: Jesús Iborra Martín Policy Department Structural and Cohesion Policies Tel: +32 (0)284 45 66 Fax: +32 (0)284 69 29 E-mail: [email protected] Manuscript completed in April 2006. Copies may be obtained through: E-mail: [email protected] Intranet: http://www.ipolnet.ep.parl.union.eu/ipolnet/cms/lang/en/pid/456 Brussels, European Parliament, 2006. The opinions expressed in this document are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the European Parliament. Reproduction and translation for non-commercial purposes are authorised, provided the source is acknowledged and the publisher is given prior notice and sent a copy. CONTENTS 1. Introduction ...............................................................................................................................3 2. Geographical framework...........................................................................................................4 -

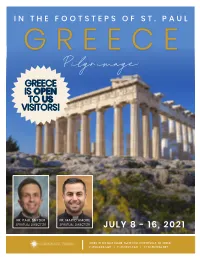

Pilgrimage GREECE IS OPEN to US VISITORS!

IN THE FOOTSTEPS OF ST. PAUL GREECE Pilgrimage GREECE IS OPEN TO US VISITORS! FR. PAUL SNYDER FR. MARIO AMORE SPIRITUAL DIRECTOR SPIRITUAL DIRECTOR JULY 8 - 16, 2021 41780 W SIX MILE ROAD, SUITE 1OO, NORTHVILLE, MI 48168 P: 866.468.1420 | F: 313.565.3621 | CTSCENTRAL.NET READY TO SEE THE WORLD? PRICING STARTING AT $1,699 PER PERSON, DOUBLE OCCUPANCY PRICE REFLECTS A $100 PER PERSON EARLY BOOKING SAVINGS FOR DEPOSITS RECEIVED BEFORE JUNE 11, 2021 & A $110 PER PERSON DISCOUNT FOR TOURS PAID ENTIRELY BY E-CHECK LEARN MORE & BOOK ONLINE: WWW.CTSCENTRAL.NET/GREECE-20220708 | TRIP ID 45177 | GROUP ID 246 QUESTIONS? VISIT CTSCENTRAL.NET TO BROWSE OUR FAQ’S OR CALL 866.468.1420 TO SPEAK TO A RESERVATIONS SPECIALIST. DAY 1: THURSDAY, JULY 8: OVERNIGHT FLIGHT FROM USA TO ATHENS, GREECE Depart the USA on an overnight flight. St. Paul the Apostle, the prolific writer of the New Testament letters, was one of the first Christian missionaries. Trace his journey through the ancient cities and pastoral countryside of Greece. DAY 2: FRIDAY, JULY 9: ARRIVE THESSALONIKI Arrive in Athens on your independent flights by 12:30pm.. Transfer on the provided bus from Athens to the hotel in Thessaloniki and meet your professional tour director. Celebrate Mass and enjoy a Welcome Dinner. Overnight Thessaloniki. DAY 3: SATURDAY, JULY 10: THESSALONIKI Tour Thessaloniki, Greece’s second largest city, sitting on the Thermaic Gulf of the Aegean Sea. Founded in 315 B.C.E. by King Kassandros, the city grew to be an important hub for trade in the ancient world. -

Downloaded from the NOA GNSS Network Website (

remote sensing Article Spatio-Temporal Assessment of Land Deformation as a Factor Contributing to Relative Sea Level Rise in Coastal Urban and Natural Protected Areas Using Multi-Source Earth Observation Data Panagiotis Elias 1 , George Benekos 2, Theodora Perrou 2,* and Issaak Parcharidis 2 1 Institute for Astronomy, Astrophysics, Space Applications and Remote Sensing (IAASARS), National Observatory of Athens, GR-15236 Penteli, Greece; [email protected] 2 Department of Geography, Harokopio University of Athens, GR-17676 Kallithea, Greece; [email protected] (G.B.); [email protected] (I.P.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 6 June 2020; Accepted: 13 July 2020; Published: 17 July 2020 Abstract: The rise in sea level is expected to considerably aggravate the impact of coastal hazards in the coming years. Low-lying coastal urban centers, populated deltas, and coastal protected areas are key societal hotspots of coastal vulnerability in terms of relative sea level change. Land deformation on a local scale can significantly affect estimations, so it is necessary to understand the rhythm and spatial distribution of potential land subsidence/uplift in coastal areas. The present study deals with the determination of the relative vertical rates of the land deformation and the sea-surface height by using multi-source Earth observation—synthetic aperture radar (SAR), global navigation satellite system (GNSS), tide gauge, and altimetry data. To this end, the multi-temporal SAR interferometry (MT-InSAR) technique was used in order to exploit the most recent Copernicus Sentinel-1 data. The products were set to a reference frame by using GNSS measurements and were combined with a re-analysis model assimilating satellite altimetry data, obtained by the Copernicus Marine Service. -

Final Report on the Analysis of Charred Plant Remains from the Late Neolithic and Bronze Age Riverside Site of Longas Elatis in Western Macedonia, Northern Greece

IWGP 2016 Paris : International Work-Group for Palaeoethnobotany 2016, 4-9 Jul 2016 Paris (France) Final report on the analysis of charred plant remains from the Late Neolithic and Bronze Age riverside site of Longas Elatis in western Macedonia, northern Greece. Dimitra Kotsachristou1, 2 1Ephorate of Antiquities of Kozani, General Secretariat of Culture, Greece 2Archaeological museum of Aiani, Kozani, Greece INTRODUCTION e-mail: [email protected] Over the last 25 years archaeobotanical sampling in western Macedonia and particularly in the region of Kozani has been intensive and systematic and the archaeobotanical material from several sites are under study or have been published (Kremasti Koiladas, Karathanou and Valamoti 2011, Karathanou et al. 2011, Kleitos, Stylianakou and Valamoti 2012, Phyllotsairi, Mavropigi, Valamoti 2011). This poster presents the final results of analysis of charred plant remains from the Late Neolithic and Bronze Age riverside settlement of Longas Elatis, adding significantly to the already known archaeobotanical material from investigated sites in western Macedonia. THE SITE UNDER STUDY The site is located in the low right bank of Aliakmon, the longest river entirely within Greek boarders (297km up to the point where it flows into the Thermaic Gulf, located immediately south of Thessaloniki regional unit) and particularly in the mild sloping terraces of adjacent hills, covering an area of 3000 m2 (fig. 1, 2). Additionally, it constituted a pole of attraction for people for permanent establishment from the Neolithic period and its use was not abandoned over time while ensured fertile and easily cultivable ground (Karamitrou-Mentesidi 2009, 2011). In the valleys and plains of the Aliakmon a number of important settlements, such as Longas, grew up as long ago as prehistoric times and went on to develop into important cities of the historical era (Karamitrou-Mentesidi and Theodorou 2009, Karamitrou-Mentesidi 2010). -

First Announcement

First Announcement www.icd2019.gr Welcome Address Dear Colleagues and Friends, It is a distinct privilege and honor for me to be invited to serve as President of the ICD- European Section for the year 2018-2019 and to have the pleasure to host the 64th Annual Meeting of the European Section in my hometown, Thessaloniki Greece. Thessaloniki, which is also called the “nymph of Thermaic Gulf”, is the second largest city and port in Greece with about one million inhabitants in its metropolitan area, located in central Northern Greece at the northwestern corner of the Aegean Sea and in the vicinity of the beautiful resort area Chalkidiki. Thessaloniki is also Greece’s second major economic, industrial, commercial and political centre; it is a major transportation hub for Greece and southeastern Europe, notably through its port. Thessaloniki was founded in 315 BC by Cassander (Kassandros) and was named after his wife, a half-sister of Alexander the Great, Thessalonike. The city is counting nowadays 2333 years of history. It was an important metropolis during the Roman Empire period and the second largest and wealthiest city of the Byzantine Empire after Constantinople. It was conquered by the Ottomans in 1430, and passed from the Ottoman Empire to Greece on November 8, 1912. The city is renowned for its festivals, events, good food and vibrant cultural life in general and is considered to be Greece’s cultural capital. International events such as the “Thessaloniki International Trade Fair” and the “Thessaloniki International Film Festival” are held annually. Thessaloniki is also home to numerous notable Byzantine monuments, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, as well as several Roman, Ottoman and Sephardic Jewish structures. -

New VERYMACEDONIA Pdf Guide

CENTRAL CENTRAL ΜΑCEDONIA the trip of your life ΜΑCEDONIA the trip of your life CAΝ YOU MISS CAΝ THIS? YOU MISS THIS? #can_you_miss_this REGION OF CENTRAL MACEDONIA ISBN: 978-618-84070-0-8 ΤΗΕSSALΟΝΙΚΙ • SERRES • ΙΜΑΤΗΙΑ • PELLA • PIERIA • HALKIDIKI • KILKIS ΕΣ. ΑΥΤΙ ΕΞΩΦΥΛΛΟ ΟΠΙΣΘΟΦΥΛΛΟ ΕΣ. ΑΥΤΙ ΜΕ ΚΟΛΛΗΜΑ ΘΕΣΗ ΓΙΑ ΧΑΡΤΗ European emergency MUSEUMS PELLA KTEL Bus Station of Litochoro KTEL Bus Station Thermal Baths of Sidirokastro number: 112 Archaeological Museum HOSPITALS - HEALTH CENTERS 23520 81271 of Thessaloniki 23230 22422 of Polygyros General Hospital of Edessa Urban KTEL of Katerini 2310 595432 Thermal Baths of Agkistro 23710 22148 23813 50100 23510 37600, 23510 46800 KTEL Bus Station of Veria 23230 41296, 23230 41420 HALKIDIKI Folkloric Museum of Arnea General Hospital of Giannitsa Taxi Station of Katerini 23310 22342 Ski Center Lailia HOSPITALS - HEALTH CENTERS 6944 321933 23823 50200 23510 21222, 23510 31222 KTEL Bus Station of Naoussa 23210 58783, 6941 598880 General Hospital of Polygyros Folkloric Museum of Afytos Health Center of Krya Vrissi Port Authority/ C’ Section 23320 22223 Serres Motorway Station 23413 51400 23740 91239 23823 51100 of Skala, Katerini KTEL Bus Station of Alexandria 23210 52592 Health Center of N. Moudania USEFUL Folkloric Museum of Nikiti Health Center of Aridea 23510 61209 23330 23312 Mountain Shelter EOS Nigrita 23733 50000 23750 81410 23843 50000 Port Authority/ D’ Section Taxi Station of Veria 23210 62400 Health Center of Kassandria PHONE Anthropological Museum Health Center of Arnissa of Platamonas 23310 62555 EOS of Serres 23743 50000 of Petralona 23813 51000 23520 41366 Taxi Station of Naoussa 23210 53790 Health Center of N. -

About Thessaloniki

INFORMATION ON THESSALONIKI Thessaloniki is one of the oldest cities in Europe and the second largest city in Greece. It was founded in 315 B.C. by Cassander, King of Macedonia and was named after his wife Thessaloniki, sister of Alexander the Great. Today Thessaloniki is considered to be one of the most important trade and communication centers in the Mediterranean. This is evident from its financial and commercial activities as well as its geographical position and its infrastructure. As a historic city Thessaloniki is well – known from its White Tower dating from the middle of the 15th century in its present form. Thessaloniki presents a series of monuments from Roman and Byzantine times. It is known for its museums, Archaeological and Byzantine as well as for its Art, Historical and War museums and Galleries. Also, it is known for its Churches, particularly the church of Agia Sophia and the church of Aghios Dimitrios, the patron Saint of the city. Thessaloniki’s infrastructure, which includes the Universities campus, the International trade, its port and airport as well as its road rail network, increases the city’s reputation; it is also famous for its entertainment, attractions, gastronomy, shopping and even more. A place that becomes a vacation resort for many citizens of Thessaloniki especially in the summer and only 45 minutes away is Chalkidiki. Chalkidiki is a beautiful place, which combines the sea with the mountain. Today, Chalkidiki is a summer resort for the people of Thessaloniki. It is really a gifted place due to its natural resources, its crystal waters and also the graphical as well as traditional villages. -

Mast@CHS Spring Seminar 04-16-2021 Summaries Discussion

https://classical-inquiries.chs.harvard.edu/mastchs-spring-seminar-2021-friday- april-16-summaries-of-presentations-and-discussion/ MASt@CHS – Spring Seminar 2021 (Friday, April 16): Summaries of Presentations and Discussion June 10, 2021 Guest Post 2021.06.10 | By Rachele Pierini and Tom Palaima §1. Rachele Pierini opened the Spring session of the MASt@CHS seminars by welcoming the participants to the session. In addition to the regular members of the MASt@CHS network and colleagues and students who have already attended previous session, new guests joined the April 16 meeting: Elena Dzukeska, Massimo Perna, Kim Shelton, Trevor Van Damme, and Malcolm H. Wiener. This seminar session was the meeting of the two Morrises. The presenters for the Spring 2021 meeting were Sarah Morris, who is a regular member of the MASt@CHS group, and Morris Silver, who resumed his treatment of the cultural significance and economic importance of purple cloth that he began guiding us through in the Winter 2021 MASt@CHS session. Figure 0. Map of northern Greece showing Methone in relation to other ancient sites, by Myles Chykerda (from Morris et al. 2020:660, fig. 1). §2.1. Sarah Morris shared with us some thoughts based on results of her field project at the site of Methone in northern Greece in the region of Pieria lying roughly between the coast of the Thermaic Gulf and Mount Olympus (Figure 0). She outlined the possible relationship between this site and the Mycenaean texts. She discussed diverse evidence, extending from Homer to ancient Greek geographic literature, also including the archeological evidence at Thermaic Methone and Mycenae in the Argolid to specific entries on the Linear B tablets from Mycenae and Pylos. -

Business Concept “Fish & Nature”

BUSINESS CONCEPT “FISH & NATURE” Marina Ross - 2014 PRODUCT PLACES FOR RECREATIONAL FISHING BUSINESS PACKAGE MARINE SPORT FISHING LAND SERVICES FRESHWATER EQUIPMENT SPORT FISHING SUPPORT LEGAL SUPPORT FISHING + FACILITIES DEFINITIONS PLACES FOR RECREATIONAL FISHING BUSINESS PACKAGE MARINE SPORT FISHING LAND SERVICES FRESHWATER EQUIPMENT SPORT FISHING SUPPORT LEGAL SUPPORT FISHING + FACILITIES PLACES FOR RECREATIONAL FISHING PRODUCT MARINE SPORT FISHING MARINE BUSINESS SECTION FRESHWATER SPORT FISHING FRESHWATER BUSINESS SECTION BUSINESS PACKAGE PACKAGE OF ASSETS AND SERVICES SERVICES SERVICES PROVIDED FOR CLIENTS RENDERING PROFESSIONAL SUPPORT TO FISHING SUPPORT MAINTAIN SAFE SPORT FISHING RENDERING PROFESSIONAL SUPPORT TO LEGAL SUPPORT MAINTAIN LEGAL SPORT FISHING LAND LAND LEASED FOR ORGANIZING BUSINESS EQUIPMENT AND FACILITIES PROVIDED EQUIPMENT + FACILITIES FOR CLIENTS SUBJECTS TO DEVELOP 1. LAND AND LOCATIONS 2. LEGISLATION AND TAXATION 3. EQUIPMENT AND FACILITIES 4. MANAGEMENT AND FISHING SUPPORT 5. POSSIBLE INVESTOR LAND AND LOCATIONS LAND AND LOCATIONS LAND AND LOCATIONS List of rivers of Greece This is a list of rivers that are at least partially in Greece. The rivers flowing into the sea are sorted along the coast. Rivers flowing into other rivers are listed by the rivers they flow into. The confluence is given in parentheses. Adriatic Sea Aoos/Vjosë (near Novoselë, Albania) Drino (in Tepelenë, Albania) Sarantaporos (near Çarshovë, Albania) Ionian Sea Rivers in this section are sorted north (Albanian border) to south (Cape Malea). -

Map 50 Macedonia Compiled by E.N

Map 50 Macedonia Compiled by E.N. Borza, 1994 Introduction Map 50 Macedonia Map 51 Thracia The single most valuable guide to Greek and Roman settlements as far east as Philippi is Papazoglou (1988). While ostensibly a treatment of Roman towns in Macedonia, it incorporates considerable information about pre-Roman periods at many sites, and includes exhaustive and valuable notes on the ancient sources and modern scholarship. Although now largely supplanted by Papazoglou on the treatment of individual sites and the road system, Hammond (1972) presents a comprehensive overview of the historical geography and topography of Macedonia. For Chalcidice, Zahrnt’s (1971) study emphasizes pre-Roman periods. TIR Philippi, covering those parts of Thrace lying within modern Greece, is generally accurate and has comprehensive bibliographies. Isaac (1986) is a useful survey with references to the ancient sources and modern scholarship. Since the 1920s much of Thrace, especially the Chersonese, has been a military zone, with the result that archaeological survey and excavation have been severely restricted. TIR Naissus provides information about hundreds of Roman sites within the modern state of Macedonia; for areas within Greece today, however, it is less reliable. References to south Slavic scholarly investigations more recent than those listed by it can be found in MAA and ArchIug. On the Greek side, two annual publications cover continuing archaeological work in the region: the summaries of recent work cited in BCH, and the archaeologists’ own reports in AEMT. RE remains a comprehensive guide to the ancient evidence for toponyms. The ancient courses of the principal rivers flowing into the central Macedonian plain are largely conjectural because over the centuries they have frequently shifted in this highly alluviated region.