The Weimar Century.”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Bauhaus and Weimar Modernism

Buchenwald Memorial, Ettersburg Castle Sömmerda (B7 / B85) 100 m weimar UNESCO World Heritage 500 m Culture City of Europe The Bauhaus and its sites in Weimar and Dessau have been on the UNESCO list of World Heritage since 1996. There are three objects in Weimar: the main building of the Bauhaus University Weimar, the former School of Applied Arts and the Haus Am Horn. Tiefurt Mansion deutschEnglish Harry-Graf-Kessler-Str. 10 5 Tiefurt Mansion Bauhaus-Universität Weimar Nietzsche Archive B Jorge-Semprùn-Platz a Oskar-Schlemmer-Str. d The building ensemble by Henry van de Velde was Friedrich Nietzsche spent the last years of his life at H e Stèphane- r 1 s revolutionary in terms of architecture at the turn of the “Villa Silberblick”. His sister established the Nietzsche Archive f Hessel-Platz e l d century. These Art School buildings became the venue here after his death and had the interior and furnishings e r S where the State Bauhaus was founded in 1919, making designed by Henry van de Velde. The current exhibition is t r a ß “Weimar” and the “Bauhaus” landmarks in the history of entitled “Kampf um Nietzsche” (“Dispute about Nietzsche”). e modern architecture. Humboldtstrasse 36 13 Mon, Wed to Sun 2pm – 5pm Geschwister-Scholl-Strasse 2 Mon to Fri 10am – 6pm | Sat & Sun 10am – 4pm Über dem Kegeltor C o u d r a y s t Erfurt (B7) r a ß e Berkaer Bahnhof 8 CRADLE, DESIGN: PETER KELER, 1922 © KLASSIK STIFTUNG WEIMAR 17 Jena (B7) 3 Tourist Information Office Weimar Haus Hohe Pappeln Weimar Municipal Museum 20 16 Markt 10, 99423 Weimar The Belgian architect Henry van de Velde, the artistic The permanent exhibition of the Municipal Museum presents Tel + 49 (0) 3643 745 0 advisor of the grand duchy, built this house for his family of “Democracy from Weimar. -

CHAPTER 2 the Period of the Weimar Republic Is Divided Into Three

CHAPTER 2 BERLIN DURING THE WEIMAR REPUBLIC The period of the Weimar Republic is divided into three periods, 1918 to 1923, 1924 to 1929, and 1930 to 1933, but we usually associate Weimar culture with the middle period when the post WWI revolutionary chaos had settled down and before the Nazis made their aggressive claim for power. This second period of the Weimar Republic after 1924 is considered Berlin’s most prosperous period, and is often referred to as the “Golden Twenties”. They were exciting and extremely vibrant years in the history of Berlin, as a sophisticated and innovative culture developed including architecture and design, literature, film, painting, music, criticism, philosophy, psychology, and fashion. For a short time Berlin seemed to be the center of European creativity where cinema was making huge technical and artistic strides. Like a firework display, Berlin was burning off all its energy in those five short years. A literary walk through Berlin during the Weimar period begins at the Kurfürstendamm, Berlin’s new part that came into its prime during the Weimar period. Large new movie theaters were built across from the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial church, the Capitol und Ufa-Palast, and many new cafés made the Kurfürstendamm into Berlin’s avant-garde boulevard. Max Reinhardt’s theater became a major attraction along with bars, nightclubs, wine restaurants, Russian tearooms and dance halls, providing a hangout for Weimar’s young writers. But Berlin’s Kurfürstendamm is mostly famous for its revered literary cafés, Kranzler, Schwanecke and the most renowned, the Romanische Café in the impressive looking Romanische Haus across from the Memorial church. -

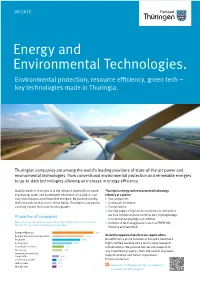

Energy and Environmental Technologies. Environmental Protection, Resource Efficiency, Green Tech – Key Technologies Made in Thuringia

09/2015 Energy and Environmental Technologies. Environmental protection, resource efficiency, green tech – key technologies made in Thuringia. Thuringian companies are among the world‘s leading providers of state-of-the-art power and environmental technologies: from conventional environmental protection and renewable energies to up-to-date technologies allowing an increase in energy efficiency. Quality made in Thuringia is in big demand, especially in waste Thuringia‘s energy and environmental technology processing, water and wastewater treatment, air pollution con- industry at a glance: trol, revitalization and renewable energies. By working closely > 366 companies with research institutions in these fields, Thuringia‘s companies > 5 research institutes can fully exploit their potential for growth. > 7 universities > leading engineering service providers in disciplines Proportion of companies such as industrial plant construction, hydrogeology, environmental geology and utilities (Source: In-house calculations according to LEG Industry/Technology Information Service, > market and technology leaders such as ENERCON, July 2013, N = 366 companies, multiple choices possible) Siemens and Vattenfall Seize the opportunities that our region offers. Benefit from a prime location in Europe’s heartland, highly skilled workers and a world-class research infrastructure. We provide full-service support for any investment project – from site search to project implementation and future expansions. Please contact us. www.invest-in-thuringia.de/en/top-industries/ environmental-technologies/ Skilled specialists – the keystone of success. Thuringia invests in the training and professional development of skilled workers so that your company can develop green, energy-efficient solutions for tomorrow. This maintains the competitiveness of Thuringian companies in these times of global climate change. -

The Beginning of the Berlin Wall Erin Honseler, Halie Mitchell, Max Schuetze, Callie Wheeler March 10, 2009

Group 8 Final Project 1 The Beginning of the Berlin Wall Erin Honseler, Halie Mitchell, Max Schuetze, Callie Wheeler March 10, 2009 For twenty-eight years an “iron curtain” divided East and West Berlin in the heart of Germany. Many events prior to the actual construction of the Wall caused East Germany’s leader Erich Honecker to demand the Wall be built. Once the Wall was built the cultural gap between East Germany and West Germany broadened. During the time the Wall stood many people attempted to cross the border illegally without much success. This caused a very unstable relationship between the government of the West (Federal Republic of Germany) and the government of the East (German Democratic Republic). In this paper we will discuss events leading up to the construction of the Berlin Wall, the government that was responsible for the construction of the Wall, how it divided Germany, and how some people tried to escape from the East to the West. Why the Berlin Wall Was Built In order to understand why the Berlin Wall was built, we must first look at the events leading up to the actual construction of the Wall in 1961. In the Aftermath of World War II Germany was split up into four different zones; each zone was controlled by a different country. The western half was split into three different sectors: the British sector, the American sector and the French sector. The Eastern half was controlled by the Soviet Union. Eventually, the three western occupiers unified their three zones and became what is known as the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG). -

Historical Aspects of Thuringia

Historical aspects of Thuringia Julia Reutelhuber Cover and layout: Diego Sebastián Crescentino Translation: Caroline Morgan Adams This publication does not represent the opinion of the Landeszentrale für politische Bildung. The author is responsible for its contents. Landeszentrale für politische Bildung Thüringen Regierungsstraße 73, 99084 Erfurt www.lzt-thueringen.de 2017 Julia Reutelhuber Historical aspects of Thuringia Content 1. The landgraviate of Thuringia 2. The Protestant Reformation 3. Absolutism and small states 4. Amid the restauration and the revolution 5. Thuringia in the Weimar Republic 6. Thuringia as a protection and defense district 7. Concentration camps, weaponry and forced labor 8. The division of Germany 9. The Peaceful Revolution of 1989 10. The reconstitution of Thuringia 11. Classic Weimar 12. The Bauhaus of Weimar (1919-1925) LZT Werra bridge, near Creuzburg. Built in 1223, it is the oldest natural stone bridge in Thuringia. 1. The landgraviate of Thuringia The Ludovingian dynasty reached its peak in 1040. The Wartburg Castle (built in 1067) was the symbol of the Ludovingian power. In 1131 Luis I. received the title of Landgrave (Earl). With this new political landgraviate groundwork, Thuringia became one of the most influential principalities. It was directly subordinated to the King and therefore had an analogous power to the traditional ducats of Bavaria, Saxony and Swabia. Moreover, the sons of the Landgraves were married to the aristocratic houses of the European elite (in 1221 the marriage between Luis I and Isabel of Hungary was consummated). Landgrave Hermann I. was a beloved patron of art. Under his government (1200-1217) the court of Thuringia was transformed into one of the most important centers for cultural life in Europe. -

Honecker's Policy Toward the Federal Republic and West Berlin

Scholars Crossing Faculty Publications and Presentations Helms School of Government Spring 1976 Contrast and Continuity: Honecker’s Policy toward the Federal Republic and West Berlin Stephen R. Bowers Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/gov_fac_pubs Part of the Other Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons, Political Science Commons, and the Public Affairs, Public Policy and Public Administration Commons Recommended Citation Bowers, Stephen R., "Contrast and Continuity: Honecker’s Policy toward the Federal Republic and West Berlin" (1976). Faculty Publications and Presentations. 86. https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/gov_fac_pubs/86 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Helms School of Government at Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 308 STEPHEN R. BOWERS 36. Mamatey, pp. 280-286. 37. Ibid., pp. 342-343. CONTRAST AND CONTINUITY: 38. The Letters of Theodore Roosevelt, Volume VIII (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1954), p. 1364. 39. Robert Ferrell, 'The United States and East Central Europe Before 1941," in Kertesz, op. cit., p. 22. HONECKER'S POLICY 40. Ibid., p. 24. 41. William R. Caspary, 'The 'Mood Theory': A Study of Public Opinion and Foreign Policy," American Political Science Review LXIV (June, 1970). 42. For discussion on this point see George Kennan, American Diplomacy (New York: Mentor Books, 1951); Walter Lippmann, The Public Philosophy (New York: Mentor Books, TOWARD THE FEDERAL 1955). 43. Gaddis, p. 179. 44. Martin Wei!, "Can the Blacks Do for Africa what the Jews Did for Israel?" Foreign Policy 15 (Summer, 1974), pp. -

September 15, 1961 Letter from Ulbricht to Khrushchev on Closing the Border Around West Berlin

Digital Archive digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org International History Declassified September 15, 1961 Letter from Ulbricht to Khrushchev on Closing the Border Around West Berlin Citation: “Letter from Ulbricht to Khrushchev on Closing the Border Around West Berlin,” September 15, 1961, History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, Published in CWIHP Working Paper No. 5, "Ulbricht and the Concrete 'Rose.'" Translated for CWIHP by Hope Harrison. SED Archives, IfGA, ZPA, Central Committee files, Walter Ulbricht's office, Internal Party Archive, J IV 2/202/130. http://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/116212 Summary: Ulbricht writes to Khrushchev regarding the closing of the border between east and west Berlin. Credits: This document was made possible with support from the Leon Levy Foundation. Original Language: German Contents: English Translation Letter from Ulbricht to Khrushchev, 15 September 1961. SED Archives, IfGA, ZPA, Central Committee files, Walter Ulbricht's office, Internal Party Archive, J IV 2/202/130.. Now that the first part of the task of preparing the peace treaty has been carried out, I would like to inform the CPSU CC Presidium about the situation. The implementation of the resolution on the closing of the border around West Berlin went according to plan. The tactic of gradually carrying out the measures made it more difficult for the adversary to orient himself with regard to the extent of our measures and made it easier for us to find the weak places in the border. I must say that the adversary undertook fewer counter- measures than was expected. The dispatch of 1500 American bandits would bother the West Berliners more than we do. -

Curriculum Vitae Germany

Historisches Institut Dr. Alexander Schmidt Akademischer Rat Universität Jena · Einrichtung · 07737 Jena Fürstengraben 13 07743 Jena Curriculum Vitae Germany Telefon: +49 36 41 9-4979 Telefax: +49 36 41 9-310 02 E-Mail: [email protected] ACADEMIC DEGREES Jena, 29. Februar 2020 M.A. (1,0, 2001, Friedrich Schiller University of Jena), Dr.phil. (summa cum laude, 2005, Friedrich Schiller University of Jena) ACADEMIC POSITION Akademischer Rat, Historisches Institut, Friedrich Schiller University of Jena PREVIOUS POSITIONS 07/2009-03/2017 Juniorprofessor of Intellectual History, Research Centre “Laboratory Enlightenment”, Friedrich Schiller University of Jena 10/2004-12/2008 Research fellow at the Collaborative Research Centre 482 “The Weimar-Jena phenomenon: Culture around 1800” (Sonderforschungsbereich 482 “Ereignis Weimar-Jena. Kultur um 1800”), Friedrich Schiller University of Jena 7/2001–1/2002 Research fellow at the Department of History (Early Modern Studies), Friedrich Schiller University of Jena GRANTS, AWARDS, SCHOLARSHIPS 7/2018 (together with Professor Paul Cheney, University of Chicago) Summer Institute for University and College Teachers sponsored by the National Endowment for the Humanities ($ 110,694), Visiting Faculty at University of Chicago 12/2017 Initial grant by the Centre for the Study of the Global Condition (Leipzig) for the “Human rights without religion?” project (5500 €) 7/2015-11/2016 Feodor-Lynen-Fellowship for Experienced Researchers (offered by the Alexander von Humboldt-Foundation) at the John U. -

The Causes of Emigration: Report from a Central Committee Brigade on Security Issues (May 24, 1961)

Volume 8. Occupation and the Emergence of Two States, 1945-1961 The Causes of Emigration: Report from a Central Committee Brigade on Security Issues (May 24, 1961) At the beginning of the 1960s, the exodus from the GDR to West Germany continued unabated. Issued a few months before the erection of the Berlin Wall, this May 1961 report by the Central Committee Brigade on Security Issues placed particular emphasis on the influence of Western contacts. The report did concede, however, that economic difficulties, bureaucratism, and arbitrariness in the granting of travel permits had a negative impact on living conditions in the GDR. Additionally, the report mentioned that Republikflucht was also motivated by a spirit of adventure and personal problems. Goal of the deployment of the brigade: Improving the public educational work of the German People’s Police in the district of Halle in connection with the fight against Republikflucht, especially among skilled workers, young people, doctors, and teachers. [ . ] The brigade worked as an independent working group in the complete brigade [Gesamtbrigade] of the Central Committee, which was under the authority of the Division for State and Legal Issues. [ . ] Causes for, reasons behind, and abetting factors in Republikflucht and recruitment methods The brigade and the German People’s Police in Halle thoroughly examined a series of flights from the republic, from the workplace to the place of residence. The process revealed a great many causes for, reasons behind, and abetting factors in Republikflucht and recruitment methods, which are closely related and work together. All cases showed the most diverse links and contact with relatives, acquaintances, and escapees in West Germany and the influence of trips and visits to the West. -

The Heritage of National Socialism: the Culture of Remembrance in Berlin (Account of a Centre for Nonviolent Action Study Tour)

Centre for Nonviolent Action Nonviolent for Centre The Heritage of National Socialism: The Culture of Remembrance in Berlin (Account of a Centre for Nonviolent Action study tour) Ivana Franović Translation: Photos: Ana Mladenović Nenad Vukosavljević Nedžad Horozović Proofreading: Alan Pleydell Design: Ivana Franović August, 2012 www.nenasilje.org Centre for Nonviolent Action Content Introduction _ 3 Anne Frank. here & now _ 16 The Topography of Terror _ 4 Environs of the concentration camp _ 17 Monument to the Murdered Jews of Europe _ 7 The Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church _ 19 Memorials to homosexuals, the Roma and Sinti The Missing House _ 20 and political opponents _ 8 The German-Russian museum _ 20 Widespread places of remembrance _ 10 Engaged art in Schöneberg _ 10 Appendix: The Jewish Museum _ 11 The Coventry Litany of Reconciliation _ 23 The German Resistance Memorial Centre _ 13 The Silent Heroes _ 15 © CNA 3 The Jewish Museum Introduction At the end of March 2012, six of us from the CNA team had the opportunity to go for a study tour to Berlin and devote a whole week to monuments in Berlin, that is those relating to the culture of remembrance. We had been waiting for this opportunity for a long time, and once we got it, we put the last ounce of effort into it. We returned full of impressions which have still not settled in us, and I think that we are not yet fully aware of all the things we’ve learned. In this paper I will try to give a review of most of the places we visited, so that we don’t forget (if indeed we ever could), but also to help sort out the main impressions. -

Thuringia.Com

www.thats-thuringia.com That’s Thuringia. Ladies and Gentlemen, Thuringia is the region where successful collaboration between entrepreneurs and researchers goes back centuries. Looking to the future has been a long-standing tradition here. Just take Carl Zeiss, Ernst Abbe, and Otto Schott, who joined forces in Jena to lay the foundations for the modern optics industry and for a productive partnership between business and science. It’s a success story that the entrepreneurs and scientists in our Free State are continuing to write to this very day. And in the process, our producers and services providers can draw upon a multifaceted research environment which currently comprises no less than nine universities and universities of applied sciences, a total of 14 institutions run by the Fraunhofer, Leibniz, Max-Planck, and Helmholtz scientific societies, as well as eight research institutions with close ties to the economy. It’s the variety and the optimal mix of locational advantages that makes Thuringia so attractive for investors from all over the world. The central location of our Land at the heart of Germany will soon become even more of an advantage thanks to the new ICE high-speed train junction in Erfurt, which will significantly reduce travelling time to Berlin, Munich, and Frankfurt am Main. International companies seeking to locate to Thuringia can choose from our many top-notch industrial sites, which are situated along major highways and also include large-scale locations for those investors in need of more space. By now, Thuringia has surpassed Baden-Württem- berg as the Federal Land within Germany with the highest number of industrial operations per 100,000 inhabitants. -

Hans Haacke Biography

P A U L A C O O P E R G A L L E R Y Hans Haacke Biography 1936 Born Cologne, Germany 1956-60 Staatliche Werkakademie (State Art Academy), Kassel, Staatsexamen (equivalent of M.F.A.) 1960-61 Stanley William Hayter's Atelier 17, Paris 1961 Tyler School of Fine Arts, Temple University, Philadelphia 1962 Moves to New York 1963-65 Return to Cologne. Teaches at Pädagogische Hochschule, Kettwig, and other institutions 1966-67 Teaches at University of Washington, Seattle; Douglas College, Rutgers University, New Jersey; Philadelphia College of Art 1967 - 2002 Teaches at Cooper Union, New York (Professor of Art Emeritus) 1973 Guest Professorship, Hochschule für Bildende Künste, Hamburg 1979 Guest Professorship, Gesamthochschule, Essen 1994 Guest Professorship, Hochschule für Bildende Künste, Hamburg 1997 Regents Lecturer, University of California, Berkeley Lives in New York (since 1965) Awards 1960 Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst (DAAD) 1961 Fulbright Fellowship 1973 John Simon Guggenheim Foundation Fellowship 1978 National Endowment for the Arts 1991 College Art Association Distinguished Artist Award for Lifetime Achievement Deutscher Kritikerpreis for 1990 Honorary Doctorate in Fine Arts, Oberlin College 1993 Golden Lion (shared with Nam June Paik), Venice Biennale 1997 Kurt-Eisner-Foundation, Munich Honorary Doctorate Bauhaus-Universität Weimar 2001 Prize of Helmut-Kraft-Stiftung, Stuttgart 2002 College Art Association Distinguished Teaching of Art Award 2004 Peter-Weiss-Preis, Bochum 2008 Honorary Doctorate, San Francisco Art Institute