Learning to Work 2 Final Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SFC Evaluation Report on the Merger to Form Glasgow Clyde College

College Post-Merger Evaluation Report June 2016 GLASGOW CLYDE COLLEGE 1 SFC post-merger evaluation of the college mergers that took place during the academic year 2013-14 In autumn 2015 the Scottish Funding Council (SFC) began a round of post-merger evaluations of the colleges that merged in the academic year 2013-14. In most cases these evaluations are scheduled to take place two years after the merger. We are making the outcome of the evaluations available on the SFC website. The first two evaluations were completed in January 2016 and the final evaluation within this tranche of mergers will be June 2016. As new reports are completed they are added to the website. SFC wrote to the colleges concerned in July 2015 to explain how SFC would carry out the evaluations and what was expected from the colleges. We noted that in carrying out the evaluations across the sector SFC would pay particular attention to the Audit Scotland Good Practice Guide: Learning the lessons of public body mergers. Colleges are responsible for the implementation of their merger and need to be able to demonstrate the delivery of benefits and performance improvements for all stakeholders including students, staff and employers as outlined in their original merger proposals. The purpose of the merger evaluation is to provide evidence of progress in delivering the intended high level benefits of the merger and to identify lessons learned that support further organisational development and wider learning for the sector. SFC recognises that good governance and leadership and a culture that is supportive of change and innovation within the merged college are also critical elements in delivering a successful merger. -

Case Study: an SCQF Learning Journey WEA Scotland Pilots Its Credit Rated Science Course

Case Study: An SCQF Learning Journey WEA Scotland Pilots its Credit Rated Science Course “An Introduction to Science in Everyday Life” – SCQF Level 4 with 3 SCQF Credit Points The Awarding Body The Workers’ Educational Association (WEA) was founded in 1903 and is the leading voluntary sector adult education organisation in Scotland. We are a charity dedicated to bringing high-quality, professional education into the heart of communities. We were assessed 'Excellent' in our last inspection in Scotland from Her Majesty's Inspectorate of Education (HMIe) and ‘Good’ by Ofsted in 2017. Learners do not need any previous knowledge or qualifications to join most of our courses, only a willingness to share their curiosity, ideas and experience. We have a special mission to raise aspirations and develop educational opportunities for the most disadvantaged. This includes providing adult literacy, numeracy, ICT, STEM and ESOL skills for employment; courses to improve health and wellbeing; creative programmes to broaden horizons and community engagement activities that encourage active citizenship. The Credit Rating Body Glasgow Clyde College is a highly respected further education college created following the mergers of Anniesland College, Cardonald College and Langside College in August 2013. The college is an SCQF Partnership Credit Rating Body authorised to provide third party credit rating for organisations who wish to have their learning programmes placed on the SCQF. The WEA course, “An Introduction to Science in Everyday Life”, supports Glasgow Clyde College’s STEM Manifesto to ensure that STEM is given prominence and status in the college and the community it serves and to build increased STEM capability in Scotland. -

Four New Colleges for Scotland

PRESS RELEASE EMBARGOED UNTIL 00.01hrs Thursday 01 August 2013 Four new colleges for Scotland Twelve colleges across Scotland have today merged to form four new institutions, marking a major milestone in the sector’s regionalisation process. The four new colleges – Ayrshire College, Fife College, Glasgow Clyde College and West College Scotland – all have principals, new boards of management and are overseen by a regional lead. They will form part of the 13 new college regions in Scotland. John Henderson, chief executive of Colleges Scotland, said: “Colleges across Scotland have been working on mergers and the regionalisation project for almost two years now and today marks a major milestone. “The new colleges will serve communities across Ayrshire, Dunbartonshire, Fife, Glasgow and Renfrewshire, providing invaluable services to their learners, employers and economies. “Each of the colleges should be congratulated for completing these mergers while carrying on with ‘business as usual’. “Regionalisation will be taken a further step forward by the end of the year with the creation of an additional four new colleges from mergers. The college sector is committed to delivering the very best for our learners and the Scottish economy.” The colleges still to merge include Cumbernauld and Motherwell colleges; John Wheatley, North Glasgow and Stow colleges; Aberdeen and Banff &Buchan colleges and Angus and Dundee Colleges.. ENDS Media contact: Sarah McDaid, Pagoda PR, 0131 556 0770/ [email protected] Notes to editors About the new colleges Today’s four new regional colleges have been formed through the merger of existing institutions. Please contact your local college’s marketing team for interview requests or for additional local information. -

Contents Introduction

FREEDOM OF INFORMATION (SCOTLAND) ACT 2002 GUIDE TO INFORMATION PUBLISHED BY GLASGOW CLYDE COLLEGE UNDER THE MODEL PUBLICATION SCHEME 2016 Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................ 2 About the Model Publication Scheme......................................................................... 2 Guide to Information ................................................................................................... 3 Availability and Formats ............................................................................................. 3 Requesting Information .............................................................................................. 3 Copyright and Re-use ................................................................................................ 4 Charges: ..................................................................................................................... 4 Contact Details ........................................................................................................... 5 Feedback or Complaints ............................................................................................ 5 Publication Timescale ................................................................................................ 6 CLASS 1: ABOUT GLASGOW CLYDE COLLEGE ................................................... 7 CLASS 2: HOW WE DELIVER OUR FUNCTIONS AND SERVICES ..................... 19 CLASS 3: HOW WE TAKE DECISIONS -

Langside College

LANGSIDE COLLEGE ANNUAL REPORT TO THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS, THE AUDITOR GENERAL AND THE SCOTTISH GOVERNMENT ON THE EXTERNAL AUDIT FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 JULY 2013 Langside College Annual Report to the Board of Management Topic Date Commencement of final visit 1 October 2013 Audit clearance meeting 29 October 2013 Presentation to Audit Committee 5 December 2013 Proposed presentation to Board of Management 12 December 2013 1 Langside College Annual Report to the Board of Management TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION PAGE TABLE OF CONTENTS .................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 2 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 3 2 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 5 3 FINANCIAL REVIEW ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 7 4 AUDIT APPROACH & KEY FINDINGS ................................................................................................................................................................................................. -

Glasgow Clyde College Annual Report on the 2013/14 Audit

GLASGOW CLYDE COLLEGE ANNUAL REPORT TO THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS, THE AUDITOR GENERAL AND THE SCOTTISH GOVERNMENT ON THE EXTERNAL AUDIT FOR THE PERIOD ENDED 31 MARCH 2014 Glasgow Clyde College Annual Report to the Board of Management Topic Date Interim visit w/c 24 February 2014 Commencement of final visit w/c 2nd June 2014 Audit clearance meeting 8 August 2014 Presentation to Audit Committee 28 August 2014 Proposed presentation to Board of Management 11 September 2014 1 Glasgow Clyde College Annual Report to the Board of Management TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION PAGE TABLE OF CONTENTS .................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 2 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 3 2 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 5 3 FINANCIAL REVIEW ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 7 4 AUDIT APPROACH & -

Institutions That Have Merged Since 2002

Institutions that have merged since 2002 (where the Council has granted strategic funds to support the process) Colleges • Coatbridge College joined New College Lanarkshire merger – April 2014. • Motherwell College and Cumbernauld College to form New College Lanarkshire – November 2013 • Aberdeen College, Banff and Buchan College to form North East Scotland College – November 2013 • Dundee College and Angus College to form Dundee and Angus College – November 2013 • John Wheatley College, North Glasgow College and Stow College to form Glasgow Kelvin College – November 2013 • Ayr College, Kilmarnock College and James Watt College (North Ayrshire campus) to form Ayrshire College – August 2013 • Cardonald College, Anniesland College and Langside College to form Glasgow Clyde College – August 2013 • Clydebank College, Reid Kerr College, and James Watt College (Inverclyde campus) to form West College Scotland – August 2013 • Carnegie College and Adam Smith College to form Fife College – August 2013 • Stevenson College, Edinburgh’s Telford College and Jewel & Esk College to form Edinburgh College – November 2012 • Central College, Glasgow and Glasgow College of Nautical Studies and Glasgow Metropolitan College to form City of Glasgow College – September 2010 • Lochaber College and Skye & Wester Ross College to form West Highland College – August 2010 • Clackmannan and Falkirk Colleges to form Forth Valley College – August 2005 • Fife and Glenrothes Colleges to form Adam Smith College – August 2005 • Glasgow College of Building & Printing and -

Financial Statements 2017/18 Twelve Months to 31 July 2018 REPORT of the BOARD of MANAGEMENT and FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 2017/18

Financial Statements 2017/18 Twelve months to 31 July 2018 REPORT OF THE BOARD OF MANAGEMENT AND FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 2017/18 GLASGOW CLYDE COLLEGE REPORT AND FINANCIAL STATEMENTS – FOR FINANCIAL PERIOD 2017/18 CONTENTS Page Overview Principal’s Report 2 Performance Report Organisation Purposes and Activities 4 Performance Analysis 9 Principal Risks and Uncertainties 17 Review of Financial Performance 19 Accountability Report Corporate Governance Report Board of Management Report 24 Corporate Governance Statement 29 Statement of the Board of Management’s Responsibilities 32 Remuneration and Staff Report 34 Professional Advisers 40 Independent Auditor’s Report 41 Statement of Accounting Policies 45 Statement of Comprehensive Income and Expenditure 51 Statement of Changes in Reserves 52 Balance Sheet 53 Statement of Cash Flows 54 Notes to the Financial Statements 55 1 REPORT OF THE BOARD OF MANAGEMENT AND FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 2017/18 OVERVIEW The purpose of the Overview Report for academic year 2018/19 is to provide summary information in respect of the College, its objectives, strategies and the risks that it faces. This section includes a statement from the Principal providing their perspective on the performance of the College over the period and provides a high level summary of College performance during the year, this is analysed in further detail in the Performance Analysis section of the report. PRINCIPAL’S REPORT The 2017/18 academic year was my first as Principal and Chief Executive of Glasgow Clyde College. Prior to my arrival at the College I had served in various roles in the college sector in England. During the past twelve months I have been profoundly struck by the commitment of members of staff throughout the College to transform the lives of those individuals who chose to study with us. -

Glasgow Colleges Regionalisation Update for GCCP Strategic Board

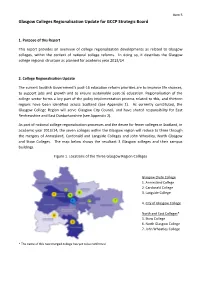

Item 5 Glasgow Colleges Regionalisation Update for GCCP Strategic Board 1. Purpose of this Report This report provides an overview of college regionalisation developments as related to Glasgow colleges, within the context of national college reforms. In doing so, it describes the Glasgow college regional structure as planned for academic year 2013/14. 2. College Regionalisation Update The current Scottish Government’s post-16 education reform priorities are to improve life chances, to support jobs and growth and to ensure sustainable post-16 education. Regionalisation of the college sector forms a key part of the policy implementation process related to this, and thirteen regions have been identified across Scotland (see Appendix 1). As currently constituted, the Glasgow College Region will serve Glasgow City Council, and have shared responsibility for East Renfrewshire and East Dunbartonshire (see Appendix 2). As part of national college regionalisation processes and the desire for fewer colleges in Scotland, in academic year 2013/14, the seven colleges within the Glasgow region will reduce to three through the mergers of Anniesland, Cardonald and Langside Colleges and John Wheatley, North Glasgow and Stow Colleges. The map below shows the resultant 3 Glasgow colleges and their campus buildings. Figure 1. Locations of the Three Glasgow Region Colleges Glasgow Clyde College 1. Anniesland College 2. Cardonald College 3. Langside College 4. City of Glasgow College North and East Colleges* 5. Stow College 6. North Glasgow College 7. John Wheatley College * The name of this new merged college has yet to be confirmed. Item 5 3. Glasgow College Regional Outcome Agreements for 2013/14 Regional Outcome Agreements were introduced by the Scottish Funding Council (SFC) in academic year 2012/13 as the primary means for SFC and colleges to work together to demonstrate the impact of the sector and its contribution to Scottish Government priorities. -

Glasgow Clyde College Financial Statements for Sixteen Month Period

Report and Financial Statements 2014/15 Sixteen months to July 2015 REPORT OF THE BOARD OF MANAGEMENT AND FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 2014/15 GLASGOW CLYDE COLLEGE REPORT AND FINANCIAL STATEMENTS – FOR SIXTEEN MONTH FINANCIAL PERIOD 2014/15 CONTENTS Page Operating and Financial Review 2 Remuneration Report 21 Statement of Corporate Governance and Internal Control 25 Statement of the Board of Management’s Responsibilities 34 Independent Auditor’s Report 36 Statement of Accounting Policies 39 Income and Expenditure Account 43 Statement of Historical Cost Surplus 44 Statement of Total Recognised Gains and Losses 44 Balance Sheet 45 Cash Flow Statement 46 Notes to the Financial Statements 47 1 REPORT OF THE BOARD OF MANAGEMENT AND FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 2014/15 OPERATING AND FINANCIAL REVIEW FOR THE SIXTEEN MONTH PERIOD ENDED 31 JULY 2015 1. NATURE, OBJECTIVES AND STRATEGIES The Board of Management of Glasgow Clyde College presents the report and audited financial statements in respect of the sixteen month financial period ended 31 July 2015. Legal and Charitable Status Glasgow Clyde College is a free standing corporate body under the provisions of the Further and Higher Education (Scotland) Act 1992, and was created from formerly the host entity of Cardonald College merging with Anniesland College and Langside College as at 1 August 2013. The College is governed by a Board of Management and receives the majority of its funding directly from the Scottish Funding Council (SFC). The College is listed on the Scottish Charity Register and is entitled, in accordance with section 13(1) of the Charities and Trustee Investment (Scotland) Act 2005, to refer to itself as a charity registered in Scotland. -

Financial Statements 2015/16

REPORT OF THE BOARD OF MANAGEMENT AND FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 2015/16 GLASGOW CLYDE COLLEGE REPORT AND FINANCIAL STATEMENTS – FOR FINANCIAL PERIOD 2015/16 CONTENTS Page Overview Depute Principal’s Report 2 Performance Report 3 Organisation Purposes and Activities 3 Performance Analysis 8 Principal Risks and Uncertainties 16 Review of Financial Performance 17 Accountability Report 21 Corporate Governance Report Board of Management Report 21 Corporate Governance Statement 28 Statement of the Board of Management’s Responsibilities 32 Remuneration and Staff Report 35 Professional Advisers 40 Independent Auditor’s Report 41 Statement of Accounting Policies 44 Statement of Comprehensive Income and Expenditure 50 Statement of Changes in Reserves 51 Balance Sheet 52 Statement of Cash Flows 53 Notes to the Financial Statements 54 1 REPORT OF THE BOARD OF MANAGEMENT AND FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 2015/16 OVERVIEW DEPUTE PRINCIPAL’S REPORT Learning and teaching continues to be at the heart of everything we do and Glasgow Clyde College is committed to providing opportunities for the widest spectrum of learners. Our portfolio of courses is built on a sound evidence base and delivered by well qualified and experienced staff. Continuous analysis and evaluation of the courses and services provided has ensured that once again, as evidenced by a student satisfaction rate of 96.4%, we have met learners’ needs. The strength and impact of our partnership, working with an extensive range of employers across almost all curriculum areas, has been recognised in a number of award nominations. These include achieving Highly Commended status in both the SEMTA - Training Partner of the Year award and the SQA Star Awards Partnership of the Year (Glasgow City Council and Glasgow Clyde College) as well as assisting NHS Greater Glasgow & Clyde in their successful SDS Award for Public Sector Employer of the Year for their Modern Apprenticeship programme, which is delivered by the College. -

Glasgow Clyde College Post Merger Evaluation Report

College Post-Merger Evaluation Report June 2016 GLASGOW CLYDE COLLEGE 1 SFC post-merger evaluation of the college mergers that took place during the academic year 2013-14 In autumn 2015 the Scottish Funding Council (SFC) began a round of post-merger evaluations of the colleges that merged in the academic year 2013-14. In most cases these evaluations are scheduled to take place two years after the merger. We are making the outcome of the evaluations available on the SFC website. The first two evaluations were completed in January 2016 and the final evaluation within this tranche of mergers will be June 2016. As new reports are completed they are added to the website. SFC wrote to the colleges concerned in July 2015 to explain how SFC would carry out the evaluations and what was expected from the colleges. We noted that in carrying out the evaluations across the sector SFC would pay particular attention to the Audit Scotland Good Practice Guide: Learning the lessons of public body mergers. Colleges are responsible for the implementation of their merger and need to be able to demonstrate the delivery of benefits and performance improvements for all stakeholders including students, staff and employers as outlined in their original merger proposals. The purpose of the merger evaluation is to provide evidence of progress in delivering the intended high level benefits of the merger and to identify lessons learned that support further organisational development and wider learning for the sector. SFC recognises that good governance and leadership and a culture that is supportive of change and innovation within the merged college are also critical elements in delivering a successful merger.