Introduction: Reproducing Englishness 1 in Pursuit of An

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Just As the Priests Have Their Wives”: Priests and Concubines in England, 1375-1549

“JUST AS THE PRIESTS HAVE THEIR WIVES”: PRIESTS AND CONCUBINES IN ENGLAND, 1375-1549 Janelle Werner A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2009 Approved by: Advisor: Professor Judith M. Bennett Reader: Professor Stanley Chojnacki Reader: Professor Barbara J. Harris Reader: Cynthia B. Herrup Reader: Brett Whalen © 2009 Janelle Werner ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT JANELLE WERNER: “Just As the Priests Have Their Wives”: Priests and Concubines in England, 1375-1549 (Under the direction of Judith M. Bennett) This project – the first in-depth analysis of clerical concubinage in medieval England – examines cultural perceptions of clerical sexual misbehavior as well as the lived experiences of priests, concubines, and their children. Although much has been written on the imposition of priestly celibacy during the Gregorian Reform and on its rejection during the Reformation, the history of clerical concubinage between these two watersheds has remained largely unstudied. My analysis is based primarily on archival records from Hereford, a diocese in the West Midlands that incorporated both English- and Welsh-speaking parishes and combines the quantitative analysis of documentary evidence with a close reading of pastoral and popular literature. Drawing on an episcopal visitation from 1397, the act books of the consistory court, and bishops’ registers, I argue that clerical concubinage occurred as frequently in England as elsewhere in late medieval Europe and that priests and their concubines were, to some extent, socially and culturally accepted in late medieval England. -

The William Cole Archive on Stained Glass Roundels for the Corpus Vitrearum

THE WILLIAM COLE ARCHIVE ON STAINED GLASS ROUNDELS FOR THE CORPUS VITREARUM Contents of the Archive NB All material is arranged alphabetically. Listed Material 1. List of Place Files: British, Overseas - arranged alphabetically according to place. Tours - arranged chronologically. 2. List of Articles by William Cole, draft and published material. 3. List of Correspondence with Museums and Organisations. 4. List of Articles about Stained Glass Roundels by other Authors. 5. List of Photographs from various Museums and Collections. 6. List of Slides. 7. Correspondence: A-G, H-P, Q-Z (listed) General, with individuals (unlisted) Unlisted Material 8. Notebooks, cassettes and manuscripts made by William Cole. 9. Corpus Vitrearum conferences. 10. A range of guidebooks and pamphlets. 11. Box of iconography reference cards. 12. William Cole‟s card index of Netherlandish and North European Roundels, by place. 1 1a. Place files Place Location Catalogue Contents of file reference Addington St Mary the Virgin, 7–73 Draft article [WC] Buckinghamshire Correspondence Alfrick St Mary Magdalene, 74–90 Correspondence Hereford & Worcester Banwell St Andrew, Avon 113–119 Correspondence Begbroke St Michael, Oxfordshire 120–137 Correspondence Berwick-upon- Holy Trinity, 138–165 Correspondence Tweed Northumberland Birtles St Catherine, Cheshire 166–211 Draft article [WC] Bishopsbourne St Mary, Kent 212–239 Correspondence Blundeston St Mary, Suffolk 236–239 Correspondence Bradford-on- Holy Trinity, Wiltshire 251–275 Correspondence Avon Photocopied images Bramley -

Pevsner's Architectural Glossary

Glossary pages new extra text:Layout 1 10/9/10 16:22 Page 1 PEVSNER’S ARCHITECTURAL GLOSSARY Glossary pages new extra text:Layout 1 10/9/10 16:22 Page 2 Nikolaus and Lola Pevsner, Hampton Court, in the gardens by Wren's east front, probably c. Glossary pages new extra text:Layout 1 10/9/10 16:22 Page 3 PEVSNER’S ARCHITECTURAL GLOSSARY Yale University Press New Haven and London Glossary pages new extra text:Layout 1 10/9/10 16:22 Page 4 Temple Street, New Haven Bedford Square, London www.pevsner.co.uk www.lookingatbuildings.org.uk www.yalebooks.co.uk www.yalebooks.com for Published by Yale University Press Copyright © Yale University, Printed by T.J. International, Padstow Set in Monotype Plantin All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections and of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers Glossary pages new extra text:Layout 1 10/9/10 16:22 Page 5 CONTENTS GLOSSARY Glossary pages new extra text:Layout 1 10/9/10 16:22 Page 6 FOREWORD The first volumes of Nikolaus Pevsner’s Buildings of England series appeared in .The intention was to make available, county by county, a comprehensive guide to the notable architecture of every period from prehistory to the present day. Building types, details and other features that would not necessarily be familiar to the general reader were explained in a compact glossary, which in the first editions extended to some terms. -

The Architecture of Sir Ernest George and His Partners, C. 1860-1922

The Architecture of Sir Ernest George and His Partners, C. 1860-1922 Volume II Hilary Joyce Grainger Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Ph. D. The University of Leeds Department of Fine Art January 1985 TABLE OF CONTENTS Notes to Chapters 1- 10 432 Bibliography 487 Catalogue of Executed Works 513 432 Notes to the Text Preface 1 Joseph William Gleeson-White, 'Revival of English Domestic Architecture III: The Work of Mr Ernest George', The Studio, 1896 pp. 147-58; 'The Revival of English Domestic Architecture IV: The Work of Mr Ernest George', The Studio, 1896 pp. 27-33 and 'The Revival of English Domestic Architecture V: The Work of Messrs George and Peto', The Studio, 1896 pp. 204-15. 2 Immediately after the dissolution of partnership with Harold Peto on 31 October 1892, George entered partnership with Alfred Yeates, and so at the time of Gleeson-White's articles, the partnership was only four years old. 3 Gleeson-White, 'The Revival of English Architecture III', op. cit., p. 147. 4 Ibid. 5 Sir ReginaldýBlomfield, Richard Norman Shaw, RA, Architect, 1831-1912: A Study (London, 1940). 6 Andrew Saint, Richard Norman Shaw (London, 1976). 7 Harold Faulkner, 'The Creator of 'Modern Queen Anne': The Architecture of Norman Shaw', Country Life, 15 March 1941 pp. 232-35, p. 232. 8 Saint, op. cit., p. 274. 9 Hermann Muthesius, Das Englische Haus (Berlin 1904-05), 3 vols. 10 Hermann Muthesius, Die Englische Bankunst Der Gerenwart (Leipzig. 1900). 11 Hermann Muthesius, The English House, edited by Dennis Sharp, translated by Janet Seligman London, 1979) p. -

The Warburg Institute and Architectural History 133 CK181 11Vaneck 1Pp Sh.Indd 134 Part Part in Brink, and Claudia

1 2 3 4 5 6 THE WARBURG INSTITUTE 7 8 AND ARCHITECTURAL HISTORY 9 10 11 12 13 Caroline van Eck 14 15 16 17 18 At first sight, classical architecture, with its continuous revivals and reworkings 19 of the forms of Greek and Roman building, would seem to offer a privileged field 20 to apply Aby Warburg’s central notion of the survival of antiquity and his view 21 of art history’s unfolding as a process of remembrance, of Mnemosyne. Yet War- 22 burg himself wrote very little on architecture, and after auspicious and impres- 23 sive beginnings by Rudolf Wittkower, Richard Krautheimer, Georg Kubler, and 24 Nikolaus Pevsner, the role of architectural history in the activities of the War- 25 burg Institute, its Library and Journal, dwindled. A brief survey of the Journal of 26 the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes shows that, up to the early 1970s, it published 27 three to four articles on architectural topics every year. Among them are classics 28 in the field that have kept their value to the present day, such as Wittkower’s arti- 29 cles on perspective and Palladianism, Robin Middleton’s article on Cordemoy, 30 or Krautheimer’s on medieval iconography.1 Beginning in the mid- 1970s, archi- 31 32 1. Richard Krautheimer, “Introduction to an ‘Iconogra- tauld Institutes 6 (1943): 154 – 64; George Kubler, “Archi- 33 phy of Mediaeval Architecture’,” Journal of the Warburg tects and Builders in Mexico, 1521 – 1550,” Journal of the and Courtauld Institutes 5 (1942): 1 – 33; Rudolf Wittkower, Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 7 (1944): 7 – 19; Robin 34 “Brunelleschi and Proportion in Perspective,”, Journal Middleton, “The Abbé de Cordemoy and the Graeco- 35 of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 16 (1953): 275 – 91; Gothic Ideal: A Prelude to Romantic Classicism,” Jour 36 Wittkower, “Pseudo- Palladian Elements in English Neo- nal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 25 (1962): Classical Architecture,” Journal of the Warburg and Cour 278 – 320. -

The English Claim to Gothic: Contemporary Approaches to an Age-Old Debate (Under the Direction of DR STEFAAN VAN LIEFFERINGE)

ABSTRACT MARY ELIZABETH BLUME The English Claim to Gothic: Contemporary Approaches to an Age-Old Debate (Under the Direction of DR STEFAAN VAN LIEFFERINGE) The Gothic Revival of the nineteenth century in Europe aroused a debate concerning the origin of a style already six centuries old. Besides the underlying quandary of how to define or identify “Gothic” structures, the Victorian revivalists fought vehemently over the national birthright of the style. Although Gothic has been traditionally acknowledged as having French origins, English revivalists insisted on the autonomy of English Gothic as a distinct and independent style of architecture in origin and development. Surprisingly, nearly two centuries later, the debate over Gothic’s nationality persists, though the nationalistic tug-of-war has given way to the more scholarly contest to uncover the style’s authentic origins. Traditionally, scholarship took structural or formal approaches, which struggled to classify structures into rigidly defined periods of formal development. As the Gothic style did not develop in such a cleanly linear fashion, this practice of retrospective labeling took a second place to cultural approaches that consider the Gothic style as a material manifestation of an overarching conscious Gothic cultural movement. Nevertheless, scholars still frequently look to the Isle-de-France when discussing Gothic’s formal and cultural beginnings. Gothic historians have entered a period of reflection upon the field’s historiography, questioning methodological paradigms. This -

The Carlyle Society

THE CARLYLE SOCIETY SESSION 2006-2007 OCCASIONAL PAPERS 19 • Edinburgh 2006 President’s Letter This number of the Occasional Papers outshines its predecessors in terms of length – and is a testament to the width of interests the Society continues to sustain. It reflects, too, the generosity of the donation which made this extended publication possible. The syllabus for 2006-7, printed at the back, suggests not only the health of the society, but its steady move in the direction of new material, new interests. Visitors and new members are always welcome, and we are all warmly invited to the annual Scott lecture jointly sponsored by the English Literature department and the Faculty of Advocates in October. A word of thanks for all the help the Society received – especially from its new co-Chair Aileen Christianson – during the President’s enforced absence in Spring 2006. Thanks, too, to the University of Edinburgh for its continued generosity as our host for our meetings, and to the members who often anonymously ensure the Society’s continued smooth running. 2006 saw the recognition of the Carlyle Letters’ international importance in the award by the new Arts and Humanities Research Council of a very substantial grant – well over £600,000 – to ensure the editing and publication of the next three annual volumes. At a time when competition for grants has never been stronger, this is a very gratifying and encouraging outcome. In the USA, too, a very substantial grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities means that later this year the eCarlyle project should become “live” on the internet, and subscribers will be able to access all the volumes to date in this form. -

The Gothic Revival Character of Ecclesiastical Stained Glass in Britain

Folia Historiae Artium Seria Nowa, t. 17: 2019 / PL ISSN 0071-6723 MARTIN CRAMPIN University of Wales THE GOTHIC REVIVAL CHARACTER OF ECCLESIASTICAL STAINED GLASS IN BRITAIN At the outset of the nineteenth century, commissions for (1637), which has caused some confusion over the subject new pictorial windows for cathedrals, churches and sec- of the window [Fig. 1].3 ular settings in Britain were few and were usually char- The scene at Shrewsbury is painted on rectangular acterised by the practice of painting on glass in enamels. sheets of glass, although the large window is arched and Skilful use of the technique made it possible to achieve an its framework is subdivided into lancets. The shape of the effect that was similar to oil painting, and had dispensed window demonstrates the influence of the Gothic Revival with the need for leading coloured glass together in the for the design of the new Church of St Alkmund, which medieval manner. In the eighteenth century, exponents was a Georgian building of 1793–1795 built to replace the of the technique included William Price, William Peckitt, medieval church that had been pulled down. The Gothic Thomas Jervais and Francis Eginton, and although the ex- Revival was well underway in Britain by the second half quisite painterly qualities of the best of their windows are of the eighteenth century, particularly among aristocratic sometimes exceptional, their reputation was tarnished for patrons who built and re-fashioned their country homes many years following the rejection of the style in Britain with Gothic features, complete with furniture and stained during the mid-nineteenth century.1 glass inspired by the Middle Ages. -

Newsletter the Society of Architectural Historians

NEWSLETTER THE SOCIETY OF ARCHITECTURAL HISTORIANS APRIL 1967 VOL. XI NO. 2 PUBLISHED FIVE TIMES A YEAR BY THE SOCIETY OF ARCHITECTURAL HISTORIANS 1700 WALNUT STREET, PHILADELPHIA, PA. 19103 GEORGE B. TATUM, PRESIDENT EDITOR: JAMES C. MASSEY, 501 DUKE STREET, ALEXANDRIA, VIRGINIA 22314. ASSOCIATE EDITOR : MARIAN CARD DONNELLY, 2175 OLIVE STREET, EUGENE, OREGON 97405 CHAPTERS PRESIDENTIAL MESSAGE Eastern Virginia (Proposed Chapter) Calvert Walke have asked the editors of the Newsletter for Tazewell, Executive Vice President of the Norfolk His enough space to express my appreciation, and that of torical Society, and other interested SAH members, are the Society, to all who replied to my recent letter proposing the establishment of a new SAH Chapter for asking for advice and assistance. Eastern Virginia. A preliminary meeting was held in Nor The response of those you proposed for member folk on April 27. For information, address, Col. Tazewell ship in the Society has been heartening, while in at 507 Boush Street, Norfolk, Va. creasing contributions from our Patron members and Missouri Valley The Missouri Valley Chapter of the SAH others continue to i11J-prove materially our balance held its organizationa l meeting April 16 at the Nelson in the treasury. We are especially grateful to those Gallery of Art in Kansas City, Mo. The following persons of you who increased your class of membership. were elected to Chapter posts: President - E.F. Corwin, We regret that to date it has not been possible Jr., Architect for the Kansas City Park Department; Vice to acknowledge promptly and individually every President- Ralph T. Coe, Assistant Director of the Nelson contribution of time, thought, and funds, but we trust Gallery of Art; Secretary-Treasurer- Donald Hoffmann, Art those concerned will recognize· that to have done so Critic of the Kansas City Star; Directors - Osmund Overby, under present conditions would have increased our University of Missouri, and Curtis Besinger, University of expenses, thereby diminishing the effectiveness of Kansas. -

Cromwelliana the Journal of the Cromwell Association

Cromwelliana The Journal of The Cromwell Association 1999 • =-;--- ·- - ~ -•• -;.-~·~...;. (;.,, - -- - --- - -._ - - - - - . CROMWELLIANA 1999 The Cromwell Association edited by Peter Gaunt President: Professor JOHN MORRILL, DPhil, FRHistS Vice Presidents: Baron FOOT of Buckland Monachorum CONTENTS Right Hon MICHAEL FOOT, PC Professor IV AN ROOTS, MA, FSA, FRHistS Cromwell Day Address 1998 Professor AUSTIN WOOLRYCH, MA, DLitt, FBA 2 Dr GERALD AYLMER, MA, DPhil, FBA, FRHistS By Roy Sherwood Miss PAT BARNES Mr TREWIN COPPLESTONE, FRGS Humphrey Mackworth: Puritan, Republican, Cromwellian Chairman: Dr PETER GAUNT, PhD, FRHistS By Barbara Coulton 7 Honorary Secretary: Mr Michael Byrd Writings and Sources III. The Siege. of Crowland, 1643 5 Town Fann Close, Pinchbeck, near Spalding, Lincolnshire, PEI I 3SG By Dr Peter Gaunt 24 Honorary Treasurer: Mr JOHN WESTMACOTT Cavalry of the English Civil War I Salisbury Close, Wokingham, Berkshire, RG41 4AJ I' By Alison West 32 THE CROMWELL ASSOCIATION was founded in 1935 by the late Rt Hon Isaac Foot and others to commemorate Oliver Cromwell, the great Puritan statesman, and to Oliver Cromwell, Kingship and the encourage the study of the history of his times, his achievements and influence. It is Humble Petition and Advice neither political nor sectarian, its aims being essentially historical. The Association By Roy Sherwood 34 seeks to advance its aims in a variety of ways which have included: a. the erection of commemorative tablets (e.g. at Naseby, Dunbar, Worcester, Preston, etc) (From time to time appeals are made for funds to pay for projects of 'The Flandric Shore': Cromwellian Dunkirk this sort); By Thomas Fegan 43 b. helping to establish the Cromwell Museum in the Old Grammar School at Huntingdon; Oliver Cromwell c. -

Brian Knight

STRATEGY, MISSION AND PEOPLE IN A RURAL DIOCESE A CRITICAL EXAMINATION OF THE DIOCESE OF GLOUCESTER 1863-1923 BRIAN KNIGHT A thesis submitted to the University of Gloucestershire in accordance with the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Arts and Humanities August, 2002 11 Strategy, Mission and People in a Rural Diocese A critical examination of the Diocese of Gloucester 1863-1923 Abstract A study of the relationship between the people of Gloucestershire and the Church of England diocese of Gloucester under two bishops, Charles John Ellicott and Edgar Charles Sumner Gibson who presided over a mainly rural diocese, predominantly of small parishes with populations under 2,000. Drawing largely on reports and statistics from individual parishes, the study recalls an era in which the class structure was a dominant factor. The framework of the diocese, with its small villages, many of them presided over by a squire, helped to perpetuate a quasi-feudal system which made sharp distinctions between leaders and led. It is shown how for most of this period Church leaders deliberately chose to ally themselves with the power and influence of the wealthy and cultured levels of society and ostensibly to further their interests. The consequence was that they failed to understand and alienated a large proportion of the lower orders, who were effectively excluded from any involvement in the Church's affairs. Both bishops over-estimated the influence of the Church on the general population but with the twentieth century came the realisation that the working man and women of all classes had qualities which could be adapted to the Church's service and a wider lay involvement was strongly encouraged. -

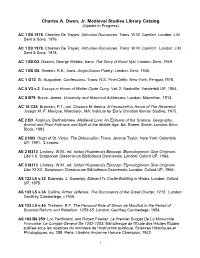

Charles A. Owen, Jr. Medieval Studies Library Catalog (Update in Progress)

Charles A. Owen, Jr. Medieval Studies Library Catalog (Update in Progress) AC 1 E8 1976 Chretien De Troyes. Arthurian Romances. Trans. W.W. Comfort. London: J.M. Dent & Sons, 1976. AC 1 E8 1978 Chretien De Troyes. Arthurian Romances. Trans. W.W. Comfort. London: J.M. Dent & Sons, 1978. AC 1 E8 D3 Dasent, George Webbe, trans. The Story of Burnt Njal. London: Dent, 1949. AC 1 E8 G6 Gordon, R.K., trans. Anglo-Saxon Poetry. London: Dent, 1936. AC 1 G72 St. Augustine. Confessions. Trans. R.S. Pine-Coffin. New York: Penguin,1978. AC 5 V3 v.2 Essays in Honor of Walter Clyde Curry. Vol. 2. Nashville: Vanderbilt UP, 1954. AC 8 B79 Bryce, James. University and Historical Addresses. London: Macmillan, 1913. AC 15 C55 Brannan, P.T., ed. Classica Et Iberica: A Festschrift in Honor of The Reverend Joseph M.-F. Marique. Worcester, MA: Institute for Early Christian Iberian Studies, 1975. AE 2 B3 Anglicus, Bartholomew. Medieval Lore: An Epitome of the Science, Geography, Animal and Plant Folk-lore and Myth of the Middle Age. Ed. Robert Steele. London: Elliot Stock, 1893. AE 2 H83 Hugh of St. Victor. The Didascalion. Trans. Jerome Taylor. New York: Columbia UP, 1991. 2 copies. AE 2 I8313 Lindsay, W.M., ed. Isidori Hispalensis Episcopi: Etymologiarum Sive Originum. Libri I-X. Scriptorum Classicorum Bibliotheca Oxoniensis. London: Oxford UP, 1966. AE 2 I8313 Lindsay, W.M., ed. Isidori Hispalensis Episcopi: Etymologiarum Sive Originum. Libri XI-XX. Scriptorum Classicorum Bibliotheca Oxoniensis. London: Oxford UP, 1966. AS 122 L5 v.32 Edwards, J. Goronwy.