The Golden Horseshoe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Excesss Karaoke Master by Artist

XS Master by ARTIST Artist Song Title Artist Song Title (hed) Planet Earth Bartender TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIM ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears E 10 Years Beautiful UGH! Wasteland 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants Belief) More Than This 2 Chainz Bigger Than You (feat. Drake & Quavo) [clean] Trouble Me I'm Different 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody's Been Sleeping I'm Different (explicit) 10cc Donna 2 Chainz & Chris Brown Countdown Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz & Kendrick Fuckin' Problems I'm Mandy Fly Me Lamar I'm Not In Love 2 Chainz & Pharrell Feds Watching (explicit) Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz feat Drake No Lie (explicit) Things We Do For Love, 2 Chainz feat Kanye West Birthday Song (explicit) The 2 Evisa Oh La La La Wall Street Shuffle 2 Live Crew Do Wah Diddy Diddy 112 Dance With Me Me So Horny It's Over Now We Want Some Pussy Peaches & Cream 2 Pac California Love U Already Know Changes 112 feat Mase Puff Daddy Only You & Notorious B.I.G. Dear Mama 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt I Get Around 12 Stones We Are One Thugz Mansion 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says Until The End Of Time 1975, The Chocolate 2 Pistols & Ray J You Know Me City, The 2 Pistols & T-Pain & Tay She Got It Dizm Girls (clean) 2 Unlimited No Limits If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 20 Fingers Short Dick Man If You're Too Shy (Let Me 21 Savage & Offset &Metro Ghostface Killers Know) Boomin & Travis Scott It's Not Living (If It's Not 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls With You 2am Club Too Fucked Up To Call It's Not Living (If It's Not 2AM Club Not -

Even More Land Available for Homes and Jobs in the Greater Golden Horseshoe

March 9, 2017 An update on the total land supply: Even more land available for homes and jobs in the Greater Golden Horseshoe For more information, contact: Marcy Burchfield Executive Director [email protected] 416-972-9199 ext. 1 Neptis | 1 An update on the total land supply: Even more land available for homes and jobs in the Greater Golden Horseshoe This is the third in a series of Briefs on the land supply for future urban development designated by municipalities across the Greater Golden Horseshoe to accommodate growth to 2031. This Brief sums up the supply of land in (a) the Designated Greenfield Area (DGA), (b) unbuilt areas within Undelineated Built-up Areas (UBUAs), (c) land added through boundary changes to Barrie and Brantford and (d) Amendment 1 to the Growth Plan. Altogether, the supply of unbuilt land for housing and employment planned until 2031 and beyond is 125,600 hectares. How much land is available for development in the Greater Golden Horseshoe? Determining how much land has been set aside to accommodate future housing and employment across the Greater Golden Horseshoe is a fluid process, because land supply data are not fixed once and for all. Ontario Municipal Board decisions, amendments to local official plans, and boundary adjustments constantly alter the numbers. In the first phase of analysis in 2013, Neptis researchers focused on estimating the extent of the “Designated Greenfield Area” (DGA).1 This was land set aside by municipalities in land budgeting exercises to accommodate the population and employment targets allocated by the Province for the period 2006–2031 in the Growth Plan for the Greater Golden Horseshoe. -

Food Asset Mapping in Toronto and Greater Golden Horseshoe Region1 Lauren Baker

LAUREN BAKER FOOD ASSET MAPPING IN TORONTO AND GREATER GOLDEN HORSESHOE REGION1 LAUREN BAKER 216 ISOCARP FOOD ASSET MAPPING IN TORONTO AND GREATER GOLDEN HORSESHOE REGION » The purpose of the mapping project was to provide a baseline for planners and policy mak- ers to: 1. understand, promote and strengthen the regional food system, 2. provide information to enable analysis to inform decision making; and, 3. plan for resilience in the face of climate variability and socio, economic, and political vulnerability. « Figure 1: The bounty of the Greenbelt harvest season. Photo credit: Joan Brady REVIEW 12 217 LAUREN BAKER The City of Toronto is the largest City in Canada the third largest food processing and manufac- with a population of 2.6 million people (2011). turing cluster in North America, and the clus- The City is known as one of the most multicul- ter uses over 60% of the agricultural products tural cities in the world, with over 140 languages grown in Ontario3. Agriculture and the broader spoken. Immigrants account for 46% of Toron- food system contribute $11 billion and 38,000 to’s population, and one third of newcomers to jobs to the provincial economy, generating $1.7 Canada settle in the city2. Needless to say, diets billion in tax revenue. are extremely diverse. This represents an oppor- In 2005 a Greenbelt was created to contain tunity for the food and agriculture sector in On- urban growth and protect the natural and cul- tario, one that many organizations are seizing. tural heritage of the region. The Greenbelt pro- The region surrounding the City of Toronto, tects 7% of Ontario’s farmland, approximately known as the Greater Golden Horseshoe (GGH), 856,424 acres and 5501 farms4, mostly outside is made up of 21 upper and single tier munici- of urban communities clustered in the Golden palities. -

Map Theft Hearing Delayed Students Robbed at Gunpoint on Campus

Reviewing The Review We read it. We laugh at it. It laughs at us. Inside, Currents takes a closer look THE CHRONICLE at The Duke Review. WEDNESDAY. OCTOBER 9. 1! ONE COPY FREE DUKE UNIVERSITY DURHAM. NORTH CAROLINA CIRCULATION: 15.000 VOL. 92. NO. 28 Map theft Students robbed at gunpoint on campus By MISTY ALLEN the incident, Nordan said, suspect after he pulled the gun activity in that area." hearing Two students were victims adding that the suspect also on them. DUPD informed Durham of an armed robbery early sports sideburns, a mustache And although the suspect Police Department officials of Tuesday morning when a man and a goatee. told them to remain in the the incident, and asked them to delayed walked into the West Union Nordan said his department bathroom for 15 minutes after be on the look-out for the sus By MISTY ALLEN Building's basement-floor received a call from the stu his departure, the students left pect. The sentencing hearing men's bathroom, pulled a small dents—both of whom wish to after about one minute to call "We're going to do every for Gilbert Bland, an art handgun on them and demand remain anonymous—at about DUPD, Nordan said. thing we can to apprehend the dealer from Coral Gables, ed that they give him their 3:10 a.m. Tuesday. DUPD offi Officers continued to search suspect in this case," Nordan Fla., who plead guilty earli money. cers responded to the scene im the immediate vicinity sur said. er this year to stealing rare Capt. -

Golden Horseshoe Food and Farming Action Plan

Photo : SF Photo GOLDEN HORSESHOE FOOD AND FARMING ACTION PLAN THE GOLDEN HORSESHOE FOOD AND FARM- ING PLAN INVOLVES THE ESTABLISHMENT OF AN INNOVATIVE GOVERNANCE BODY TO PRO- MOTE COLLABORATION BETWEEN SEVERAL LO- CAL GOVERNMENTS WITHIN A CITY REGION, AS WELL AS A RANGE OF OTHER ORGA- NIZATIONS WITH AN INTEREST IN THE Durham FOOD AND FARMING ECONOMY — IN- York CANADA CLUDING LARGE-SCALE FARMERS. IT Peel Toronto UNDERLINES THE VALUE OF ESTABLISH- ING CLEAR TERMS OF REFERENCE AND Halton MEDIATION TOOLS, AND FORG- ING INNOVATIVE GOVERNANCE STRUCTURES TO MANAGE THE Hamilton COMPLEXITIES OF FOOD SYS- Niagara Golden Horseshoe TEM PLANNING AT THE UR- BAN-RURAL INTERFACE. 52 CASE STUDIES 01 WHAT MAKES URBAN FOOD POLICY HAPPEN? GOLDEN HORSESHOE The Golden Horseshoe geographical region In 2011/12 seven municipalities of the Gold- stretches around the Western shores of Can- en Horseshoe — the cities of Hamilton and ada’s Lake Ontario, including the Greater To- Toronto, and the top-tier54 Municipal Regions ronto Area and neighbouring cities, towns of Durham, Halton, Niagara, Peel, and York — and rural communities52. It is one of the most adopted a common plan to help the food and densely populated parts of North America, and farming sector remain viable in the face of land an infux of educated, afuent professionals use pressures at the urban-rural interface, as has led to rapid development and expansion well as other challenges such as infrastructure of the cities. gaps, rising energy costs, and disjoined policy implementation. Yet historically the Golden Horseshoe has been an important agricultural region; more The Golden Horseshoe Food and Farming Plan than a million acres of productive farmland 2021 (GHFFP) (Walton, 2012a) is a ten-year plan remain in the Greenbelt and in the shrink- with fve objectives: ing peri-urban and rural spaces between • to grow the food and farming cluster; the urban hubs. -

Quinn Hedges Song List 033018.Numbers

Song Ar'st Don't Follow Alice in Chains Got Me Wrong Alice in Chains Nutshell Alice in Chains Ramblin Man Allman Brothers Band When You Say Nothing at All Allison Krauss Arms of a Woman Amos Lee Seen It All Before Amos Lee Keep it Loose, Keep it Tight Amos Lee What’s Been Going On Amos Lee Violin Amos Lee The Weight Band Up On Cripple Creek Band It Makes No Difference Band Here There and Everywhere Beatles Blackbird Beatles Till There Was You Beatles Golden Slumbers Beatles Here Comes The Sun Beatles While My Guitar Gently Weeps Beatles Across The Universe Beatles In My Life Beatles Something Beatles Yesterday Beatles Two of Us Beatles The Luckiest Ben Folds Army Ben Folds Fred Jones pt. 2 Ben Folds Brick Ben Folds Forever Ben Harper Another Lonely Day Ben Harper Burn One Down Ben Harper Not Fire Not Ice Ben Harper She's Always a Woman To Me Billy Joel Hard to Handle Black Crows Can't Find My Way Home Blind Faith Change Blind Melon No Rain Blind Melon Knocking on Heaven's Door Bob Dylan Tangled Up In Blue Bob Dylan You Aint' Goin Nowhere Bob Dylan I Shall Be Released Bob Dylan Stir it Up Bob Marley Flume Bon Iver The Way it Is Bruce Hornsby Streets of Philadelphia Bruce Springsteen Mexico Cake She Aint Me Carrie Rodriguez !1 Drive Cars Trouble Cat Stevens Wild World Cat Stevens Wicked Game Chris Isaak Yellow Coldplay Trouble Coldplay Don't Panic Coldplay Warning Sign Coldplay Sparks Coldplay Fix You Coldplay Green Eyes Coldplay The Scientist Coldplay Fix You Coldplay In My Place Coldplay Omaha Counting Crows A Long December Counting Crows -

Golden Horseshoe Economic Profile

SECTION 3 DEMOGRAPHIC GROWTH Project Coordinated By: This Section Prepared by: SECTION 3 - Demographic Growth 3.1 Introduction The objective of this section is to present a demographic profile for the Golden Horseshoe (GH) using the most recent (2011) census data.1 This section incorporates data from earlier census periods where available and allows for the identification of key demographic profiles and trends regarding population, immigration, social and cultural impacts and their marketing implications. The data shows profiles and trends for each of the participating municipalities and thus differences in key markets and locations are profiled. Except where indicated, data in this section is from the Statistics Canada censuses of 2006 and 2011. Starting in 2011, information previously collected by the mandatory long-form census questionnaire was collected as part of the voluntary National Household Survey (NHS). Caution should therefore be exercised in comparing 2011 data very closely with data from previous censuses.2 3.2 Population Growth The population of the GH and its municipalities has increased from 6.5 million in 2006 to 7 million in 2011, and now accounts for 55% of Ontario’s population. This represents a growth rate of 8% for the entire GH region over the five year period. The highest rates of growth have been experienced by Halton (14%), York (15%) and Peel (11%) which immediately surround Toronto. As further evidence of growth pressures being experienced in the GH, it is worth noting that Milton, Canada’s fastest growing municipality, grew by 57% over the period.3 Figure 3.1a below shows the growth rate for each upper tier municipality. -

Whereas It Has Been the Desire of the Town of Markham for Decades to See the Langstaff Planning Area Redevelop from a Mixed

Mr. Chair and Members of Council, it is with mixed emotion that I must make changes to my notice of motion put forward at our last meeting, I am sure that you can understand Mr. Chair how difficult it is for me to embrace a plan put forward by a Liberal Premier, but the Premiers announcement on June 15 to extend the Yonge Subway to Highway #7 was not only common sense, but it is what the Communities of Richmond Hill, Vaughan, Markham and indeed all residents of York Region need to implement “Places to Grow” and is what I have been working so hard to achieve, so thank you Mr. Premier and I did wear a red tie today I would like to state that the motion is seconded by Mayor Emmerson who is known to have Liberal leanings. Yonge Subway Motion Moved by: Regional Councillor Jim Jones Seconded by: Mayor Wayne Emmerson Whereas it has been the desire of the Town of Markham for decades to see the Langstaff planning area redevelop to a High End Urban Centre; and Whereas the Province of Ontario has in the past five years through the Central Ontario Smart Growth Plan report “Shape the Future” and the current Growth Plan for the Greater Golden Horseshoe designated the Langstaff planning area and the Richmond Hill Centre as the Richmond Hill/Langstaff Gateway and one of the four Urban Growth Centres in York Region; and Whereas Urban Growth Centres are – “to accommodate and support major transit infrastructure” and “to serve as high density major employment centres that will attract provincially, nationally or international significant employment uses” -

Got Me Wrong

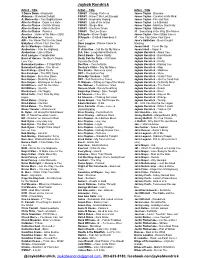

Jaykob Kendrick Artist - Title Artist - Title Artist - Title 3 Doors Down - Kryptonite CSN&Y - Change Partners James Taylor - Blossom Alabama – Dixieland Delight CSN&Y - Haven't We Lost Enough James Taylor - Carolina in My Mind A. Morissette – You Oughta Know CSN&Y - Helplessly Hoping James Taylor - Fire and Rain Alice in Chains - Down in a Hole CSN&Y - Lady of the Island James Taylor - Lo & Behold Alice in Chains - Got Me Wrong CSN&Y - Simple Man James Taylor - Machine Gun Kelly Alice in Chains - Man in the Box CSN&Y - Southern Cross James Taylor - Millworker Alice in Chains - Rooster CSN&Y - The Lee Shore JT - Something in the Way She Moves America – Horse w/ No Name ($20) D’Angelo – Brown Sugar James Taylor - Sweet Baby James Amy Winehouse – Valerie D’Angelo – Untitled (How does it JT - You Can Close Your Eyes AW – You Know That I’m No Good feel?) Jane's Addiction - Been Caught Babyface - When Can I See You Dave Loggins - Please Come to Stealing Arctic Monkeys - Arabella Boston Jason Isbell – Cover Me Up Audioslave - I Am the Highway D. Allan Coe - Call Me By My Name Jason Isbell – Super 8 Audioslave - Like a Stone D.A. Coe - Long-Haired Redneck Jaykob Kendrick - About You Avril Lavigne - Complicated David Bowie - Space Oddity Jaykob Kendrick - Barrelhouse Band of Horses - No One's Gonna Death Cab for Cutie – I’ll Follow Jaykob Kendrick - Fall Love You You into the Dark Jaykob Kendrick - Firefly Barenaked Ladies – If I had $1M Des’Ree – You Gotta Be Jaykob Kendrick - Kissing You Barenaked Ladies - One Week Destiny’s Child – Say My Name Jaykob Kendrick - Map Ben E King – Stand By Me Dire Straits - Romeo & Juliet Jaykob Kendrick - Medicine Ben Erickson - The BBQ Song DBT – Decoration Day Jaykob Kendrick - Muse Ben Harper - Burn One Down Drive-By Truckers - Outfit Jaykob Kendrick - Nuckin' Futs Ben Harper - Steal My Kisses DBT - Self-Destructive Zones Jaykob Kendrick – On the Good Foot Ben Harper - Waiting on an Angel D. -

AC/DC BONFIRE 01 Jailbreak 02 It's a Long Way to the Top 03 She's Got

AC/DC AEROSMITH BONFIRE PANDORA’S BOX DISC II 01 Toys in the Attic 01 Jailbreak 02 Round and Round 02 It’s a Long Way to the Top 03 Krawhitham 03 She’s Got the Jack 04 You See Me Crying 04 Live Wire 05 Sweet Emotion 05 T.N.T. 06 No More No More 07 Walk This Way 06 Let There Be Rock 08 I Wanna Know Why 07 Problem Child 09 Big 10” Record 08 Rocker 10 Rats in the Cellar 09 Whole Lotta Rosie 11 Last Child 10 What’s Next to the Moon? 12 All Your Love 13 Soul Saver 11 Highway to Hell 14 Nobody’s Fault 12 Girls Got Rhythm 15 Lick and a Promise 13 Walk All Over You 16 Adam’s Apple 14 Shot Down in Flames 17 Draw the Line 15 Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap 18 Critical Mass 16 Ride On AEROSMITH PANDORA’S BOX DISC III AC/DC 01 Kings and Queens BACK IN BLACK 02 Milk Cow Blues 01 Hells Bells 03 I Live in Connecticut 02 Shoot to Thrill 04 Three Mile Smile 05 Let It Slide 03 What Do You Do For Money Honey? 06 Cheesecake 04 Given the Dog a Bone 07 Bone to Bone (Coney Island White Fish) 05 Let Me Put My Love Into You 08 No Surprize 06 Back in Black 09 Come Together 07 You Shook Me All Night Long 10 Downtown Charlie 11 Sharpshooter 08 Have a Drink On Me 12 Shithouse Shuffle 09 Shake a Leg 13 South Station Blues 10 Rock and Roll Ain’t Noise Pollution 14 Riff and Roll 15 Jailbait AEROSMITH 16 Major Barbara 17 Chip Away the Stone PANDORA’S BOX DISC I 18 Helter Skelter 01 When I Needed You 19 Back in the Saddle 02 Make It 03 Movin’ Out AEROSMITH 04 One Way Street PANDORA’S BOX BONUS CD 05 On the Road Again 01 Woman of the World 06 Mama Kin 02 Lord of the Thighs 07 Same Old Song and Dance 03 Sick As a Dog 08 Train ‘Kept a Rollin’ 04 Big Ten Inch 09 Seasons of Wither 05 Kings and Queens 10 Write Me a Letter 06 Remember (Walking in the Sand) 11 Dream On 07 Lightning Strikes 12 Pandora’s Box 08 Let the Music Do the Talking 13 Rattlesnake Shake 09 My Face Your Face 14 Walkin’ the Dog 10 Sheila 15 Lord of the Thighs 11 St. -

Gritting Teeth: a Memoir of Unhealthy Love Samantha L

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Masters Theses & Specialist Projects Graduate School 12-2010 Gritting Teeth: A Memoir of Unhealthy Love Samantha L. Day Western Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/theses Part of the Creative Writing Commons, and the Social Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Day, Samantha L., "Gritting Teeth: A Memoir of Unhealthy Love" (2010). Masters Theses & Specialist Projects. Paper 230. http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/theses/230 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses & Specialist Projects by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GRITTING TEETH: A MEMOIR OF UNHEALTHY LOVE A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of English Western Kentucky University Bowling Green, Kentucky In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts By Samantha L. Day December 2010 GRITTING TEETH: A MEMOIR OF UNHEALTHY LOVE Date Recommended Alo V. ;3 ~~(?~ ,I DirecoTOf Thesis ~ P~A.~ )4- '2J.,,~11 Dean, Graduate Studies and Research Date -- ---------i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Many thanks to my thesis director, Dale Rigby, for his input, encouragement, and mentorship over the past year. I also want to thank my other committee members, David LeNoir and Wes Berry, for their patience and support. I owe my parents, Carol and John Nomikos, a million times over for putting me up when I had nowhere else to go and kicking me in the ass when I was ready to give up. And to April Schofield: Thanks for having faith in my writing and my ability to pull through. -

![City of Brantford Comments on the Proposed Amendment to the Growth Plan for the Greater Golden Horseshoe [Financial Impact - None]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0729/city-of-brantford-comments-on-the-proposed-amendment-to-the-growth-plan-for-the-greater-golden-horseshoe-financial-impact-none-2930729.webp)

City of Brantford Comments on the Proposed Amendment to the Growth Plan for the Greater Golden Horseshoe [Financial Impact - None]

Alternative formats and communication supports available upon request. Please contact [email protected] or 519-759-4150 for assistance. Date February 5, 2019 Report No. 2019-85 To Chair and Members Committee of the Whole – Community Development From Paul Moore General Manager, Community Development 1.0 Type of Report Consent Item [ ] Item For Consideration [x] 2.0 Topic City of Brantford Comments on the Proposed Amendment to the Growth Plan for the Greater Golden Horseshoe [Financial Impact - none] 3.0 Recommendation A. THAT Report 2019-85, City of Brantford Comments on the Proposed Amendment to the Growth Plan for the Greater Golden Horseshoe, BE RECEIVED; and B. THAT a copy of Report 2019-85 BE APPENDED to the City’s official comments submitted to the Ontario Growth Secretariat at the Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing; and C. THAT a copy of the City’s official comments submitted to the Ontario Growth Secretariat at the Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing, including a copy of Report 2019-85, BE FORWARDED to Will Bouma, MPP, Brantford-Brant. 4.0 Purpose and Overview The purpose of this Report is to advise Council about the proposed amendment to the Growth Plan for the Greater Golden Horseshoe. On January 15, 2019 the Report No. 2019-85 Page 2 February 5, 2019 Province issued the proposed amendment (Amendment 1) to the Environmental Registry of Ontario (ERO #013-4504) with a deadline to receive comments by February 28, 2019. This Report provides an overview and Planning Staff’s comments regarding the proposed amendment and three related proposals.