Power Play: Sexual Harassment in the Middle School

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Occupational Therapy Games & Activity List 2019-2020

Occupational Therapy Games & Activity List 2019-2020 Compiled by Stacey Szklut MS, OTR/L & South Shore Therapies Staff Children learn through play and active exploration. The suggestions below may be helpful in choosing appropriate toys for holidays and other special times. They include sensory based activities to provide organizing sensation and encourage the development of body awareness, as well as games to promote eye- hand coordination, visual perception and planning. Approximate ages or skill levels have been given to help guide your choices. Many items can be purchased at toy stores or through the catalogues listed. Ask your occupational therapist for help in deciding which games or toys are the best choices for your child. Games to Develop Coordination, Problem Solving and Visual Perception: Younger Ages (3-6 years) Older Kids (7 and up) Acorn Soup Acuity Ants in the Pants Amazing Labyrinth Game Avalanche Fruit Stand Backseat Drawing Barbecue Party Batik Busytown (by Richard Scarry) Battleship Cat in the Hat I Can Do That! Blink Charades for Kids Blokus Cootie Bounce Off Crazy Cereal Brain vs Brain Puzzle Game (Young Explorers) Crocodile Hop Burger Mania Disney Jr Super Stretchy Game Cheese Louise Don’t Break the Ice Connect Four/ Conniption Don’t Spill the Beans Cover Your Tracks (Thinkfun) Dream Cakes Crab Stack Elefun Cranium Cadoo Elephant Balancing Game Crowded Waters Feed the Woozle Cubeez Frankie’s Food Truck Fiasco Doodle Dice Gobblet Gobblers Doodle Quest Gumball Grab (Lakeshore) Get the Picture Dot-to-Dot Race Hit the Hat Go Go Gelato Honey Bee Tree Guess Who Hungry Hungry Hippos Hang On Harvey I Spy Bingo and Memory Games IQ Fit Journey Through Time Eye Found it! Game Jenga Loopin’ Chewie/Loopin’ Louie Kerplunk/ Tumble Monkeying Around Laser Chess (Thinkfun) Mr. -

Occupational Therapy Games & Activity List

Occupational/Speech and Language Therapy Games & Activity List 2009-2010 Compiled by Stacey Szklut MS,OTR/L & South Shore Therapies Staff Children learn through play and active exploration. Many toys and games can encourage learning and develop skills in planning and sequencing, eye-hand coordination, visual perception, concept development and fine motor control. These suggestions may be helpful in choosing appropriate toys for the holidays, birthdays and other special times. They include sensory based activities to provide organizing sensation and encourage the development of body awareness, as well as games to encourage the development of specific skills and language concepts. Approximate ages or skill levels have been given to help guide your choices. Many items can be purchased at toy stores or through the catalogues listed. Ask your occupational or speech therapist for help in deciding which games or toys are the best choices for your child. Games to Develop Coordination, Problem Solving and Visual Perception: Younger Ages (3-6 years) Older Kids (7 and up) 3D Labyrinth Aftershock! (Learning Express) Animal Soup Game (Learning Express) Amazing Labyrinth Game (Sensational Kids, Discovery Toys) Ants in the Pants Batik (Mindware) Bouncin’ Bunnies (Highlights) Battling Tops Buckaroo Battleship Cadoo & Balloon Lagoon Blink (Learning Express) Charades for Kids Blokus (Mindware, Highlights) Colorforms Dress-up Game (Therapro) Bulls Eye Ball Cootie Connect Four Cranium Hullabaloo Cover Your Tracks (Thinkfun Games) Don’t Break the Ice Cranium -

P R O C E E D I N G S of the of the United States

103rd 11/29/06 9:23 AM Page 1 (Black plate) 109th Congress, 2nd Session.......................................................House Document 109-145 P R O C E E D I N G S OF THE 103rd NATIONAL CONVENTION OF THE VETERANS OF FOREIGN WARS OF THE UNITED STATES [SUMMARY OF MINUTES] Nashville, Tennessee : : : August 24 - August 30, 2002 103rd 11/29/06 9:23 AM Page I (Black plate) 109th Congress, 2nd Session.......................................................House Document 109-145 PROCEEDINGS of the 103rd ANNUAL CONVENTION OF THE VETERANS OF FOREIGN WARS OF THE UNITED STATES (SUMMARY OF MINUTES) Nashville, Tennessee August 24-30, 2002 Referred to the Committee on Veterans’Affairs and ordered to be printed. U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 2006 30-736 U.S. CODE, TITLE 44, SECTION 1332 NATIONAL ENCAMPMENTS OF VETERANS’ ORGANIZATIONS; PROCEEDINGS PRINTED ANNUALLY FOR CONGRESS The proceedings of the national encampments of the United Spanish War Veterans, the Veterans of Foreign Wars of the United States, the American Legion, the Military Order of the Purple Heart, the Veterans of World War I of the United States, Incorporated, the Disabled American Veterans, and the AMVETS (American Veterans of World War II), respec- tively, shall be printed annually, with accompanying illustrations, as sepa- rate House documents of the session of the Congress to which they may be submitted. [Approved October 2, 1968.] II LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL VETERANS OF FOREIGN WARS OF THE UNITED STATES, KANSAS CITY, MISSOURI December, 2002 Honorable Dennis Hastert, The Speaker U.S. House of Representatives Washington, D.C. 20515 DEAR MR. SPEAKER: In conformance with the provisions of Public Law No. -

Tower Views June 2020

Tower Views June 2020 Patricia’s Travels, Part 1 atricia Sargent, age 70, has traveled extensively in the US and Great Britain and P briefly to Mexico and Canada. Her photos of the places she has visited, along with her journal, document the highlights of her trips. Now that she is unable to travel, these are her memories about specific journeys. She says that the most memorable trips are “what I’ve fallen into”. Patricia’s planned journeys to places of interest began when she was in her late 40’s. About 5 years earlier, she made some life changes that made her travels possible. She sold her car and relied on public transportation and also chose not be a homeowner. Her frugality and a favorable work situation got her started. Patricia did very little traveling while she was growing up in Minnesota. At age 17, her grandparents took her to Chicago, where they enjoyed the Museum of Science and Industry and the lake. They rode on the el train, which felt new and fascinating to Patricia. A second trip to Chicago took place years later when her boss’s wife’s passed on some frequent flyer miles. This time, Patricia went to the Sears Tower and ate at a “white linen restaurant” where she had her first (delicious) spinach salad. At the age of 48 Patricia made her first trip to New York City to see a Gershwin concert at Carnegie Hall. She “scrimped and saved” for about a year and planned with a friend to make the visit happen. -

Family Friendly

Family Friendly Listed by Age Name Category Age # of Players Difficulty Time Barrier Battles F/War 3+ 2 Beetle Game (Cootie) Chld 3+ 2-4 Candyland Chld 3+ 2-4 Katamino F 3+ 1-2 Sequence: Kids F 3+ 2-4 Snakes & Ladders Chld 3+ 2-6 Imagidice! F 4+ 2-12 Blokus Abs 5+ 2-4 Der Schwarze Pirat Chld 5+ 2-4 Dominoes: Broncos F 5+ 2-10 Gioco dell 'undici / Jeu de <<onze>> CG 5+ 2-6 Parcheesi (Royal Edition) F 5+ 2-6 Pirate's Blast Chld 5+ 2 Superfight P 5+ 3-10 Crazy Cats Chld 5+ 2-5 War & Pieces F 5+ 2-4 Close Up: Art Card Game F 5+ 2-5 Astro Trash F 6+ 2-5 Catan Jr. Str 6+ 2-4 Checkers: Broncos F 6+ 2 Checkers: Cola F 6+ 2 Chess: Super Mario F 6+ 2 Connect 4 F/Chld 6+ 2 Differ3nce F 6+ 2-6 Guess Who Chld 6+ 2 Joomba! Chld/P 6+ 2-8 Jr Scotland Yard F 6+ 2-4 Marrakech F 6+ 2-4 Mouse Trap Chld 6+ 2-4 Operation Chld 6+ 1-6 Pictureka! P 6+ 2-7 Quixo F 6+ 2-4 Qwirkle Str 6+ 2-4 Page 1 of 13 Family Friendly Listed by Age Name Category Age # of Players Difficulty Time Sorry! F 6+ 2-4 Uno F 6+ 2-10 Yahtzee F 6+ 2-10 Circus Flohcati F 6+ 2-5 Reiner Knizia's Amazing Flea Circus F/Chld 6+ 2-6 Balk F 7+ 2-4 Bananagrams F 7+ 1-8 Bandu F/P 7+ 2-8 Carcassone F 7+ 2-5 Catan: Dice Game Str 7+ 1-4 Cowabunga F 7+ 2-5 Exploding Kittens P 7+ 2-5 Gold Digger F 7+ 2-5 Night of the Grand Octopus F 7+ 3-5 Sequence F 7+ 2-12 Spot It F 7+ 2-8 Spot It: Broncos F 7+ 2-8 You've Got Crabs P 7+ 4-10 Blink F 7+ 2-3 Gold Digger F 7+ 2-5 Flick'em Up! F/Thm 7+ 2-10 13 Clues F 8+ 2-6 Bang! The Dice Game F 8+ 3-8 Battleship: Pirates of the Caribbean F 8+ 2 Bedpans + Broomsticks F -

Maximum Ride T H E ANGEL EXPERIMENT

Maximum Ride T H E ANGEL EXPERIMENT James Patterson WARNER BOOKS NEW YORK BOSTON Copyright © 2005 by Suejack, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review. Warner Vision and the Warner Vision logo are registered trademarks of Time Warner Book Group Inc. Time Warner Book Group 1271 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020 Visit our Web site at www.twbookmark.com First Mass Market Edition: May 2006 First published in hardcover by Little, Brown and Company in April 2005 The characters and events portrayed in this book are fictitious. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is coincidental and not intended by the author. Cover design by Gail Doobinin Cover image of girl © Kamil Vojnar/Photonica, city © Roger Wood/Corbis Logo design by Jon Valk Produced in cooperation with Alloy Entertainment Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Maximum Ride : the angel experiment / by James Patterson. — 1st ed. p.cm. Summary: After the mutant Erasers abduct the youngest member of their group, the "bird kids," who are the result of genetic experimentation, take off in pursuit and find themselves struggling to understand their own origins and purpose. ISBN: 0-316-15556-X(HC) ISBN: 0-446-61779-2 (MM) [1. Genetic engineering — Fiction. 2. Adventure and adventurers — Fiction.] 1. Title. 10 9876543 2 1 Q-BF Printed in the United States of America For Jennifer Rudolph Walsh; Hadley, Griffin, and Wyatt Zangwill Gabrielle Charbonnet; Monina and Piera Varela Suzie and Jack MaryEllen and Andrew Carole, Brigid, and Meredith Fly, babies, fly! To the reader: The idea for Maximum Ride comes from earlier books of mine called When the Wind Blows and The Lake House, which also feature a character named Max who escapes from a quite despicable School. -

Occupational Therapy Games & Activity List

OCCUPATIONAL THERAPY AND LEARNING DISABILITIES: Occupational Therapy Games & Activity List Linda Palmstrom, MS, OTR/L Children learn through play. Many toys and games can be For Visual Perception used to help your child develop body awareness, eye-hand coordination, visual perception and writing skills. These Candyland Chutes & Ladders Stay Alive suggestions may be helpful in choosing appropriate games Trouble Headache Honey Bee Tree and toys for holidays, birthdays or other special times. Ask Parquetry Puzzles Take 5 your occupational therapist for help deciding which games Simon Boggle Mastermind or toys best meet your child’s needs. Pallino Pizza Party Tricky Fingers Checkers Mankela Perfection Hand Skills & Coordination Superfection Chess Spider Attack Don’t Wake Daddy Blast Out For Writing Skills Splat Gnip Gnop Early Birds Grape Escape Willie Go Boom Elefun Dot to Dot Pencil Grips Scribblers’ Slobberin’ Sam Lickin’ Lizards Hot Potato B comes After A Mazes Adapted Pencils Snackin’ Safari Go! Go! Worms Acrobats Stencils Squiggle Writer Pen Mazes Knock Out Beehive Melvin Fun Pads Magnadoodle Crayons & Markers Go Monkey Go Blockhead Snapazoo Scribblers’ First Copy Book Hunt for Treasure Kerplunk Thin Ice Booby Trap Bug Gun Cootie For Sensory Motor Development & Coordination Hi Ho Cherry-O Tipsy Tower Giggle Wiggle Don’t Get Rattled Ants in the Pants Operation Sit & Spin Toss Across Hoppity Hop Don’t Break the Ice Barrel of Monkeys Monkey Mania Swings Trapezes Sleds & Saucers Pen the Pig Wild Webber Bed Bugs Pop-A-Lot Frisbee Mr. Potato -

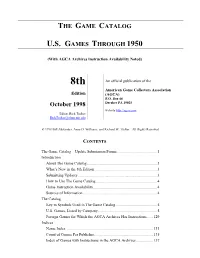

PDF of the 8Th Edition

THE GAME CATALOG U.S. GAMES THROUGH 1950 (With AGCA Archives Instruction Availability Noted) 8th An official publication of the American Game Collectors Association Edition (AGCA) P.O. Box 44 October 1998 Dresher PA 19025 website http://agca.com Editor, Rick Tucker [email protected] © 1998 Bill Alexander, Anne D. Williams, and Richard W. Tucker. All Rights Reserved. CONTENTS The Game Catalog—Update Submission Forms........................................1 Introduction About The Game Catalog.....................................................................3 What’s New in the 8th Edition..............................................................3 Submitting Updates..............................................................................3 How to Use The Game Catalog ............................................................4 Game Instruction Availability...............................................................4 Sources of Information.........................................................................4 The Catalog Key to Symbols Used in The Game Catalog.........................................5 U.S. Games, Listed by Company..........................................................5 Foreign Games for Which the AGCA Archives Has Instructions......129 Indices Name Index .....................................................................................131 Count of Games Per Publisher..........................................................135 Index of Games with Instructions in the AGCA Archives.................137 -

THE MILWAUKE MAGAZINE ! '" J H' I,,Wn Wjl11li11ll1lll

IIi ""I "I """" ""I II""" ""I I=rmnm ""I , Ii ,," "'ii'li' L:.t}iiii" 'ii' 'ii' ,'ii' ,,,',ii,' THE MILWAUKE MAGAZINE ! '" j H' I,,wn WJl11lI11ll1lll ECEMBER, 1926 HE annual question is in everybody's Tmind. The annual gift list is in everybody's pocket. Here is just the right present for son or daughter, for best friend, for close business associate-in fact MGift for 8verybody The Remington Portable Typewriter It may be selected with the assutanCe that it is the recognized leader-in sales and popularity. It meets every requirement of personal writ ing. It is the world's lightest writing machine with standard' keyboard--:tips the scales at only 8.Y2" pounds net. .Afid it is the most compact of all typewriters-fits in a carrying case only four inches high. It is faster than the speed demands of even the most expert user; and its dependability is Remington dependability. From every standpoint it is the gift for everybody. Terms as low as $5 monthly. Sold by Remington branches and dealers everywhere. Send for our booklet" For You - For Every body." Address Dept. 134. REMINGTON TYPEWRITER COMPANY 374 Broadway New York Branches Everywhere Remington Typewriter Company of Canada, Ltd. 68 King Street. West. Toromo REMINGTON PORTABLE Remington Typewri te_f Remington-made Paragon Ribbons '. and Red Seal {'.arbon Papers always make good impressions A MA'CHINE FOR EVERY PURPOS M~.R 2 r..,."ea, Cone DetroJ.t,AUcb. 1'.t: Co.. b.." sus: ~ \ \ \ _ f \ .. ,-"," St. I -~--- "\ -------.Ji \ \, Eve re We· -troduced Our Own HEADLIGHT SPECIAL. WEAVB EIG 1M Headlight Overalls were unsurpassable NOW-with this incf~dibly TOUGH, STRONG and LONGER . -

Milton Bradley Unit Study in Publicthe Domain Where Copyrightterm Isauthor’S Life Plus70 Years

Milton Bradley Unit Study In thepublic domain where copyrightterm isauthor’s life plus70 years. Subjects: Reading, Math, Writing, History, Design ©2019 Randi Smith www.peanutbutterfishlessons.com Teacher Instructions Thank you for downloading our Milton Bradley Unit Study! It was created to be used with the book: Who Was Milton Bradley?. You may incorporate other books about Milton Bradley, as well. Here is what is included in the study: Pages 3-7: Facts about Milton Bradley: Notetaking sheets with answer key. Pages 8-12: Timeline of Milton Bradley’s Life and Company: Students may write on timeline or cut and glue events provided. Pages 13-17: Game Design Plan with Templates: Children can use the organizer to design their own game. Templates for making their own custom dice and game board are included. Pages 18-19: Patent Application Children can practice their writing and drawing skills by creating a patent application for their game or another invention. Page 20-27: Starting a Business Math Activity: Children can practice their math skills while thinking through how a business decides to price a product or service. Answer key is provided. A worksheet is provided to help them think through how they would price their game they designed in the earlier activity. Page 28: Compare and Contrast Games Children can work on their analyzing skills by picking two games and comparing them. Also refer to our post: Milton Bradley FREE Unit Study for: 1. A list of popular Milton Bradley games. 2. Rebus puzzles to solve. 3. A video about how to make your own zoetrope. -

A Hilltowns Halloween!

“Elections belong to the people.” — Abraham Lincoln Country JournalDevoted to the Needs of the Hilltowns Becket, Blandford, Chester, Chesterfield, Cummington, Goshen, Huntington, Middlefield, Montgomery, Otis, Plainfield, Russell, Sandisfield, Westhampton, Williamsburg, Worthington A TURLEY PUBLICATION ❙ www.turley.com November 5, 2020 ❙ Vol. 42, No. 28 ❙ 75¢ www.countryjournal.turley.com WORTHINGTON A Hilltowns Halloween! CHESTER Licenses Trunk-or-treat focus of community effort By Shelby Macri bylaw The Recreation Committee held a trunk-or-treat for Halloween at the Emery Street Ball Field, where a one-way path was set up for fami- hearing lies to safely dress up and pikck up candy. There were cars set up one By Peter Spotts parking space or more away from each other to maintain social dis- The discussion of the tance. proposed Marijuana Bylaw There were plastic pumpkins focused heavily around the set up in between cars to make it number of licenses allowable obvious that cars couldn’t park next in town at a Planning Board to each other. People donated their public hearing on Friday, jack-o-lanterns to Kathy Engwer to Oct. 30. help line the entrance of the trunk- The bylaw as writ- ten would allow licenses TRUNK-OR-TREAT, page 8 equal to 20% of the number From left, Hampshire Regional High School Seniors Larry Weeks, Ashlynn Packey, Jerry Creek, and of liquor licenses in town, Grace Stanek are a group of superheroes for the Senior Halloween Party on Monday, Nov. 2. See HAMPSHIRE which is five. This means more photos on page 10. Photos by Shelby Macri. -

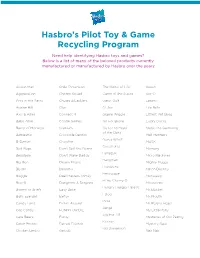

Hasbro's Pilot Toy & Game Recycling Program

Hasbro’s Pilot Toy & Game Recycling Program Need help identifying Hasbro toys and games? Below is a list of many of the beloved products currently manufactured or manufactured by Hasbro over the years: Action Man Child Dimension The Game of Life Koosh Aggravation Chomp Squad Game of the States Kre-O Ants in the Pants Chutes & Ladders Gator Golf Larami Avalon Hill Clue GI Joe Lite Brite Axis & Allies Connect 4 Giggle Wiggle Littlest Pet Shop Baby Alive Cootie Games Go For Broke Lucky Ducks Barrel of Monkeys Cranium Go to the Head Magic the Gathering of the Class Battleship Crocodile Dentist Mall Madness Guess Who? B-Daman Crossfire MASK Guesstures Bed Bugs Don’t Spill the Beans Memory Hanazuki Beyblade Don’t Wake Daddy Micro Machines Hangman Big Ben Dream Phone Mighty Muggs Headache Blythe Dropmix Milton Bradley Heroscape Boggle Duel Masters (Xm2) Monopoly Hi Ho Cherry-O Bop-It Dungeons & Dragons Mousetrap Hungry Hungry Hippos Boxers or Briefs Easy Bake Mr. Bucket i-Dog Bulls-Eye Ball Elefun Mr. Mouth India Candy Land Fishin’ Around Mr. Potato Head Jenga Cap Candy FUNNY OR DIE My Little Pony Joy For All Care Bears Furby Mysteries of Old Peking Kenner Catch Phrase Furreal Friends Mystery Date Kid Dimension Chicken Limbo Galoob Nak Nak Nerf Pound Puppies Stay Alive No Brainer Puzz 3D Strawberry Shortcake Oddzon Products Rack-O Stretch Armstrong Operation Risk Subbuteo Ouija Rook Super Soaker Outburst Scattergories Taboo Parcheesi Scrabble Taste Game Parker Brothers Scruples Tiger Electronics Pay Day Shoezies Tonka Perfection Simon Transformers Pictionary Sindy Trivial Pursuit Picture Perfect Skip-It Trouble Pictureka Sorry Twister Pie Face Speak Out Visionaries Play-Doh Spirograph Yahtzee Playskool Splat!.