Marketizing Media Control in Post-Tiananmen China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Asian Social Science, ISSN 1911-2017, Vol. 4, No. 2, October

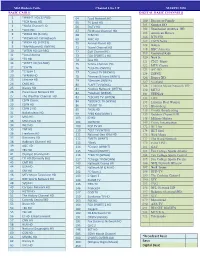

Asian Social Science October, 2008 Contents Spaces for Talk: Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) and Genuine Dialogue in an 3 International Advocacy Movement Alana Mann A Study on Applying the Variation Theory to Chinese Communicative Writing 14 Mei-yi Cheng, Chi-ming Ho Understanding the Risk of Futures Exchange: Evidence from SHFE 30 Xuyi Wang, Wenting Shi Media Salience and the Process of Framing: Coverage of the Professor Prostitution 35 Li Li Urban Sprawl and Its Financial Cost: - A Conceptual Framework 39 Shahriza bt Osman, Abdul Hadi Nawawi, Jamalunlaili Abdullah The Media and Our Understanding of World: From Toronto School to Situationism 51 Yixin Tong Essentials for Information Coordination in Supply Chain Systems 55 Qing Zhang Generic Skills to Reduce Failure Rates in an Undergraduate Accounting Information System Course 60 Dr Raymond Young, Chadi Aoun A Study on the Finance Transfer Payment of Government-Subsidized Student's Loan (GSSL) 71 Wei Huang, Hong Shen 99% Normal Adjudication and 1% Supernormal Adjudication------ Posner Paradigm and Construction of 81 Chinese Scholar-Type Judge Mechanism Min Niu, Fang Chen Some Plants Are More Equal Than Others or Not? 85 Y. Han Lau Application of Clothing Accessories in Clothing Display Design 90 Rui Guo Dynamic Design of Compensation System Based on Diversified Project Features–Taking the Project 93 Manager as an Example Liwei Liu, Erdong Zhao Communal Living Environment in Low Cost Housing Development in Malaysia 98 Dasimah Bt Omar Changes in Consumers Behavior at Fitness Clubs among Chinese Urban Residents—Dalian as an Example 106 Bin Wang, Chunyou Wu, Wenhui Quan A Comparison and Research on the Sino-U.S Character Education 111 Baoren Su The Promotion of Chinese Language Learning and China’s Soft Power 116 Jeffrey Gil 1 Vol. -

How China's Leaders Think: the Inside Story of China's Past, Current

bindex.indd 540 3/14/11 3:26:49 PM China’s development, at least in part, is driven by patriotism and pride. The Chinese people have made great contributions to world civilization. Our commitment and determination is rooted in our historic and national pride. It’s fair to say that we have achieved some successes, [nevertheless] we should have a cautious appraisal of our accomplishments. We should never overestimate our accomplish- ments or indulge ourselves in our achievements. We need to assess ourselves objectively. [and aspire to] our next higher goal. [which is] a persistent and unremitting process. Xi Jinping Politburo Standing Committee member In the face of complex and ever-changing international and domes- tic environments, the Chinese Government promptly and decisively adjusted our macroeconomic policies and launched a comprehensive stimulus package to ensure stable and rapid economic growth. We increased government spending and public investments and imple- mented structural tax reductions. Balancing short-term and long- term strategic perspectives, we are promoting industrial restructuring and technological innovation, and using principles of reform to solve problems of development. Li Keqiang Politburo Standing Committee member I am now serving my second term in the Politburo. President Hu Jintao’s character is modest and low profile. we all have the high- est respect and admiration for him—for his leadership, perspicacity and moral convictions. Under his leadership, complex problems can all get resolved. It takes vision to avoid major conflicts in soci- ety. Income disparities, unemployment, bureaucracy and corruption could cause instability. This is the Party’s most severe test. -

Online Corruption-Reporting, Internet Censorship, and the Limits of Responsive Authoritarianism

Online Corruption-Reporting, Internet Censorship, and the Limits of Responsive Authoritarianism by Jack Hoskins BA, University of Victoria, 2015 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of History © Jack Hoskins, 2017 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Supervisory Committee Online Corruption Reporting, Internet Censorship, and the Limits of Responsive Authoritarianism by Jack Hoskins BA, University of Victoria, 2015 Supervisory Committee Dr. Guoguang Wu (Department of History) Supervisor Dr. Colin Bennett (Department of Political Science) Outside Member iii Abstract This thesis traces the development of the Chinese government’s attempts to solicit corruption reports from citizens via online platforms such as websites and smartphone applications. It argues that this endeavour has proven largely unsuccessful, and what success it has enjoyed is not sustainable. The reason for this failure is that prospective complainants are offered little incentive to report corruption via official channels. Complaints on social media require less effort and are more likely to lead to investigations than complaints delivered straight to the government, though neither channel is particularly effective. The regime’s concern for social stability has led to widespread censorship of corruption discussion on social media, as well as a slew of laws and regulations banning the behaviour. Though it is difficult to predict what the long- term results of these policies will be, it seems likely that the regime’s ability to collect corruption data will remain limited. -

Contemporary China: a Book List

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY: Woodrow Wilson School, Politics Department, East Asian Studies Program CONTEMPORARY CHINA: A BOOK LIST by Lubna Malik and Lynn White Winter 2007-2008 Edition This list is available on the web at: http://www.princeton.edu/~lynn/chinabib.pdf which can be viewed and printed with an Adobe Acrobat Reader. Variation of font sizes may cause pagination to differ slightly in the web and paper editions. No list of books can be totally up-to-date. Please surf to find further items. Also consult http://www.princeton.edu/~lynn/chinawebs.doc for clicable URLs. This list of items in English has several purposes: --to help advise students' course essays, junior papers, policy workshops, and senior theses about contemporary China; --to supplement the required reading lists of courses on "Chinese Development" and "Chinese Politics," for which students may find books to review in this list; --to provide graduate students with a list that may suggest books for paper topics and may slightly help their study for exams in Chinese politics; a few of the compiler's favorite books are starred on the list, but not much should be made of this because such books may be old or the subjects may not meet present interests; --to supplement a bibliography of all Asian serials in the Princeton Libraries that was compiled long ago by Frances Chen and Maureen Donovan; many of these are now available on the web,e.g., from “J-Stor”; --to suggest to book selectors in the Princeton libraries items that are suitable for acquisition; to provide a computerized list on which researchers can search for keywords of interests; and to provide a resource that many teachers at various other universities have also used. -

CONTEMPORARY CHINA: a BOOK LIST (Winter 1999 — FIRST ON-LINE EDITION, MS Word, L&R Margins 0.9") by Lynn White

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY: Woodrow Wilson School, Politics Department, East Asian Studies Program CONTEMPORARY CHINA: A BOOK LIST (Winter 1999 — FIRST ON-LINE EDITION, MS Word, L&R margins 0.9") by Lynn White This list of items in English has several purposes: --to help advise students' course essays, junior papers, policy workshops, and senior theses about contemporary China; --to supplement the required reading lists of the seminars WWS 576a/Pol. 536 on "Chinese Development" and Pol. 535 on "Chinese Politics," as well as the undergraduate lecture course, Pol. 362; --to provide graduate students with a list that can help their study for comprehensive exams in Chinese politics; a few of the compiler's favorite books are starred on the list, but not too much should be made of this, because some such books may be too old for students' purposes or the subjects may not be central to present interests; --to supplement a bibliography of all Asian serials in the Princeton Libraries that was compiled long ago by Frances Chen and Maureen Donovan. Students with specific research topics should definitely meet Laird Klingler, who is WWS Librarian and the world's most constructive wizard. This list cannot cover articles, but computer databases can. Rosemary Little and Mary George at Firestone are also enormously helpful. Especially for materials in Chinese, so is Martin Heijdra in Gest Library (Palmer Hall; enter up the staircase near the "hyphen" with Jones Hall). Other local resources are at institutes run by Chen Yizi and Liu Binyan (for current numbers, ask at EAS, 8-4276). Professional bibliographers are the most neglected major academic resource at Princeton. -

Tri-Start TV-CTV MIL-DTL-38999 Series III EN3645 Subminiature Cylindrical Connectors High Performance Threaded Cylindrical Connectors Amphenol

Tri-Start TV-CTV MIL-DTL-38999 Series III EN3645 subminiature cylindrical connectors High performance threaded cylindrical connectors Amphenol Connecting people + technology www.amphenol-socapex.com Tri-Start™ TV-CTV Amphenol NOTES 2 Tri-Start™ TV-CTV Amphenol Tri-Start™ TV-CTV TABLE OF Contents TECHNICAL CHARACTERISTICS ........................................................................ 6 • General characteristics .............................................................................................................6 • Mechanical characteristics .........................................................................................................7 • Environmental characteristics ......................................................................................................8 • Electrical characteristics ............................................................................................................9 • Insert arrangements ............................................................................................................. 10 • Coding – Polarization ............................................................................................................ 15 STANDARD RANGE. .16 TV METALLIC SHELLS ............................................................................................................... 16 • Aluminium shells presentation ................................................................................................... 16 • Bronze shells presentation ...................................................................................................... -

2020 March Channel Line up with Pricing Color

B is Mid-Hudson Cable Channel Line UP MARCH 2020 BASIC CABLE DIGITAL BASIC CHANNELS 2 *WMHT HD (17 PBS) 64 Food Network HD 100 Discovery Family 3 *FOX News HD 65 TV Land HD 101 Science HD 4 *NASA Channel HD 66 TruTV HD 102 Destination America HD 5 *QVC HD 67 FX Movie Channe l HD 105 American Heroes 6 *WRGB HD (6-CBS) 68 TCM HD 106 BTN HD 7 *WCWN HD CW Network 69 AMC HD 107 ESPN News 8 *WXXA HD (FOX23) 70 Animal Planet HD 108 Babytv 9 *My4AlbanyHD (WNYA) 71 Travel Channel HD 118 BBC America 10 *WTEN HD (10-ABC) 72 Golf Channel HD 119 Universal Kids 11 *Local Access 73 FOX SPORTS 1 HD 12 *FX HD 120 Nick Jr. 74 fuse HD 121 CMT Music 13 *WNYT HD (13-NBC) 75 Tennis Channel HD 122 MTV Classic 17 *EWTN 76 *LIGHTtv (WNYA) 123 IFC HD 19 *C-Span 1 77 *Comet TV (WCWN) 124 ESPNU 20 *WRNN HD 78 *Heroes & Icons (WNYT) 126 Disney XD 23 Lifetime HD 79 *Decades (WNYA) 127 Viceland 24 CNBC HD 80 *LAFF TV (WXXA) 128 Lifetime Movie Network HD 25 Disney HD 81 *Justice Network (WTEN) 130 MTV2 26 Paramount Network HD 82 *Stadium (WRGB) 131 TEENick 27 The Weather Channel HD 83 *ESCAPE TV (WTEN) 132 LIFE 28 ESPN Classic 84 *BOUNCE TV (WXXA) 133 Lifetime Real Women 29 ESPN HD 86 *START TV 135 Bloomberg 30 ESPN 2 HD 95 *HSN HD 138 Trinity Broadcasting 31 Nickelodeon HD 99 *PBS Kids(WMHT) 139 Outdoor Channel HD 32 MSG HD 103 ID HD 148 Military History 33 MSG PLUS HD 104 OWN HD 149 Crime Investigation 34 WE! HD 109 POP TV HD 172 BET her 35 TNT HD 110 *GET TV (WTEN) 174 BET Soul 36 Freeform HD 111 National Geo Wild HD 175 Nick Music 37 Discovery HD 112 *METV (WNYT) -

China Human Rights Report 2009

臺灣民主基金會 Taiwan Foundation for Democracy 本出版品係由財團法人臺灣民主基金會負責出版。臺灣民主基金會是 一個獨立、非營利的機構,其宗旨在促進臺灣以及全球民主、人權的 研究與發展。臺灣民主基金會成立於二○○三年,是亞洲第一個國家 級民主基金會,未來基金會志在與其他民主國家合作,促進全球新一 波的民主化。 This is a publication of the Taiwan Foundation for Democracy (TFD). The TFD is an independent, non-profit foundation dedicated to the study and promotion of democracy and human rights in Taiwan and abroad. Founded in 2003, the TFD is the first democracy assistance foundation established in Asia. The Foundation is committed to the vision of working together with other democracies, to advance a new wave of democratization worldwide. 本報告由臺灣民主基金會負責出版,報告內容不代表本會意見。 版權所有,非經本會事先書面同意,不得翻印、轉載及翻譯。 This report is published by the Taiwan Foundation for Democracy. Statements of fact or opinion appearing in this report do not imply endorsement by the publisher. All rights reserved. No portion of the contents may be reproduced in any form or by any means without prior written permission of the publisher. Taiwan Foundation for Democracy China Human Rights Report 2009 CONTENTS Foreword ....................................................................................................................i Chapter I: Preface ............................................................................................. 1 Chapter II: Social Rights .......................................................................... 25 Chapter III: Political Rights ................................................................... 39 Chapter IV: Judicial Rights ................................................................... -

Distribution Agreement in Presenting This

Distribution Agreement In presenting this thesis or dissertation as a partial fulfillment of the requirements for an advanced degree from Emory University, I hereby grant to Emory University and its agents the non-exclusive license to archive, make accessible, and display my thesis or dissertation in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known, including display on the world wide web. I understand that I may select some access restrictions as part of the online submission of this thesis or dissertation. I retain all ownership rights to the copyright of the thesis or dissertation. I also retain the right to use in future works (such as articles or books) all or part of this thesis or dissertation. Signature: _____________________________ ______________ Tianyi Yao Date Crime and History Intersect: Films of Murder in Contemporary Chinese Wenyi Cinema By Tianyi Yao Master of Arts Film and Media Studies _________________________________________ Matthew Bernstein Advisor _________________________________________ Tanine Allison Committee Member _________________________________________ Timothy Holland Committee Member _________________________________________ Michele Schreiber Committee Member Accepted: _________________________________________ Lisa A. Tedesco, Ph.D. Dean of the James T. Laney School of Graduate Studies ___________________ Date Crime and History Intersect: Films of Murder in Contemporary Chinese Wenyi Cinema By Tianyi Yao B.A., Trinity College, 2015 Advisor: Matthew Bernstein, M.F.A., Ph.D. An abstract of -

Post-Disaster Psychosocial Capacity Building for Women in a Chinese Rural Village

Int J Disaster Risk Sci (2019) 10:193–203 www.ijdrs.com https://doi.org/10.1007/s13753-019-0221-1 www.springer.com/13753 ARTICLE Post-disaster Psychosocial Capacity Building for Women in a Chinese Rural Village 1,2,3 1 3 4 Timothy Sim • Jocelyn Lau • Ke Cui • Hsi-Hsien Wei Published online: 20 May 2019 Ó The Author(s) 2019 Abstract Mental health interventions following disasters Keywords China Á Natural hazard-induced have been criticized as individualistic, incomplete, and disasters Á Post-disaster recovery Á Psychosocial capacity culturally insensitive. This article showcases the effects of building Á Success case method Á Women’ empowerment a culturally relevant and sustainable psychosocial capacity- building project at the epicenter of the 2008 Wenchuan Earthquake. Specifically, the project focuses on women, a 1 Introduction group that has received limited attention in post-disaster recovery in China. This qualitative research study (N = 14) Disaster vulnerability is complex; it captures a combination sheds light on the characteristics and processes of the of characteristics of the individual, group, or community, implementation of a post-disaster psychosocial intervention as well as the impact of social, economic, cultural, and project in rural China. In addition, by adopting the Success political factors. All of these variables affect one’s ability Case Method as an evaluation approach, this study eluci- to anticipate, cope with, and recover from a disaster dates its effects on the psychological and social changes of (Wisner et al. 2004; Gil-Rivas and Kilmer 2016). Among the disaster victims. The findings capture five aspects of survivors, women have been identified as one of the most psychosocial changes: enriched daily life, better mood, vulnerable groups during and after disasters, due to their enhanced self-confidence, increased willingness to social- physical vulnerability and disadvantaged position in many ize, and the provision of mutual help. -

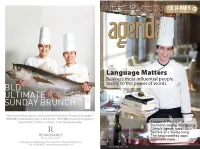

Language Matters Beijing's Most Infl Uential People Testify to the Power of Words

北京爱见达广告DM FEB 24-MAR 9 北京爱见达广告有限公司 京工商印广登字 201000068 号 ISSUE 73, THU-WED 北京市朝阳区建国路 93 号 10 号楼 2801 第 73 期 2011 年 2 月 17 日印 Language Matters Beijing's most infl uential people testify to the power of words Flavors of Portugal at the Hilton Beijing Wangfujing China’s literary wars Secrets of a Weibo kong The best wordless apps and much more 广告征订热线 5820 7700 广告DM THU, FEB 24 – WED, MAR 9 AGENDA 1 编制:北京爱见达广告有限公司 Managing Editor Jennifer Thomé Editorial Assistant Adeline Wang Visual Planning Joey Guo Art Director Susu Luo Photographers Shelley Jiang, Sui, Judy Zhou, Kara Chin, Biswarup Ganguky and Flickr user willsfca Contributors Nikolaus Fogle, Astrid Stuth, Marla Fong 广告总代理:深度体验国际广告(北京)有限公司 Advertising Agency: Immersion International Advertising (Beijing) Co., Limited 广告热线:5820 7700 Designers Yuki Jia, Helen He, Li Xing, Li Yang Distribution Jenny Wang, Victoria Wang Marketing Skott Taylor, Cindy Kusuma, Cao Yue, Jiang Lei Sales Manager Elena Damjanoska Account Executives Geraldine Cowper, Lynn Cui, Keli Dal Bosco, Sally Fang, Gloria Hao, Ashley Lendrum, Maggie Qi, Hailie Song, Jackie Yu, Sophia Zhou Inquiries Editorial: [email protected] Listings: [email protected] Distribution: [email protected] Sales: [email protected] Marketing: [email protected] Sales Hotline: (010) 5820 7700 Cover image: Hilton Beijing Wangfujing Executive Sous Chef Ricardo Bizarro at Vasco’s. Photo by Mishka Photography. 2 AGENDA THU, FEB 24 – WED, MAR 9 广告DM LETTER FROM THE EDITOR Love words? So do we! Through the course of history, words have been used to win hearts, crush spirits, make money and find enlighten- ment. -

Innovationspolitik Im Globalen Süden

Innovationspolitik im Globalen Süden Eine vergleichende Fallstudie aufstrebender ICT-Industrien in Indien und China Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Philosophischen Fakultät der Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität zu Bonn vorgelegt von Chengzhan Zhuang aus Schanghai, VR China Bonn, 2018 Gedruckt mit der Genehmigung der Philosophischen Fakultät der Rheinischen Friedrich- Wilhelms-Universität Bonn Zusammensetzung der Prüfungskommission: Prof. Dr. Tilman Mayer (Vorsitzender) Prof. Dr. Xuewu GU (Guachter und Betreuer) Prof. Dr. Maximilian Mayer (Zweitgutachter) Prof. Dr. Christoph Antweiler (Weiteres prüfungsberechtigtes Mitglied) Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 08.11.2017 1 Danksagung Zunächst geht mein größter Dank an Herrn Professor Xuewu Gu, der mich dazu inspiriert hat, vor Jahren nach Deutschland zu ziehen, um dort meine Promotionsforschung zu beginnen. Im Prozess der Promotion konnte ich in vielerlei Hinsicht von seiner Beratung im fachlichen wie sprachlichen profitieren. Ein besonderer Dank gilt auch Herrn Professor Maximilian Mayer. Ich kann mich noch an die Tage und Nächte erinnern, in denen wir nicht nur über den Inhalt dieser Dissertation, sondern auch über europäische Politik, China und die Beziehungen zwischen Technologie, Gesellschaft und Mensch diskutierten. Weiter danke ich Herrn Professor Tilman Mayer für die einwandfreie Organisation und Leitung des Prüfungsausschusses, der mir maßgebliche Ratschläge für die Dissertation geben konnte. Dabei bin ich auch Herrn Professor Christoph Antweiler für seine Teilnahme am Prüfungsaus- schuss dankbar. Er konnte wertvolle Fragen aufwerfen, die einen besonderen Mehrwert für meine Forschung dargestellt haben. Ein besonderer Dank geht auch an Herrn Tim Wenniges und die Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, die mich vor allem auch in den schwierigen Phasen meiner Dissertation unterstützten. Ohne sie hätte wohl die Gefahr bestanden, den Promotionsprozess aufzugeben.