Low-Water Crossings: Geomorphic, Biological

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

American Title a Sociation ~ ~

OFFICIAL PUBLICATION AMERICAN TITLE A SOCIATION ~ ~ VOUJME XXXVI JUNE, 1957 NUMBER 6 TITLE NEWS Official Publication of THE AMERICAN TITLE ASSOCIATION 3608 Guardian Building-Detroit 26, Michigan Volume XXXVI June, 1957 Number 6 Table of Contents Introduction-The Federal Highway Program ......... ... ................ .. .................... 2 J. E. Sheridan Highway Laws Relating to Controlled Access Roads ..... .. ....... ........... 6 Norman A. Erbe Title Companies and the Expanded Right of Way Problems ...... ............. .. 39 , Daniel W. Rosencrans Arthur A. Anderson Samuel J. Some William A . Thuma INTRODUCTION The Federal Highway Program J. E. SHERIDAN We are extremely grateful to Nor veloped its planning sufficiently to man A. Erbe, Attorney General of the show to the satisfaction of the dis State of Iowa, for permission to re trict engineer the effect of the pro print his splendid brief embracing posed construction upon adjace.nt the highway laws of various states property, the treatment of access con relating to the control in access roads. trol in the area of Federal acquisi Mr. Erbe originally presented this m tion, and that appropriate arrange narrative form before the convention ments have been made for mainte of the Iowa Title Association in May nance and supervision over the land of this year. As is readily ascertain to be acquired and held in the name able, this is the result of a compre of the United States pending transfer hensive study of various laws touch· of title and jurisdiction to the State ing on the incidents of highway regu or the proper subdivision thereof." lations. Additionally, we are privi It is suggested that our members leged to carry the panel discussion bring this quoted portion to the at of the American Right of Way Asso tention of officers of the Highway ciation Convention held in Chicago, Department and the office of its legal May 16 and 17, dealing with "Title division, plus the Office of the Attor Companies and the Expanded Right ney General within the members' ju of Way Problems". -

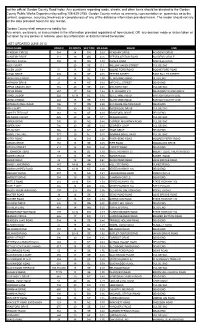

This Gordon County Online Road Index Is a Public Resource of General Information

This Gordon County Online Road Index is a public resource of general information. The Gordon County Road Index contained herein is not the official Gordon County Road Index. Any questions regarding roads, streets, and other items should be directed to the Gordon County Public Works Department by calling 706-629-2785. Gordon County makes no warranty, representation or guarantee as to the content, sequence, accuracy,timeliness or completeness of any of the database information provided herein. The reader should not rely on the data provided herein for any reason. Gordon County shall assume no liability for: Any errors, omissions, or inaccuracies in the information provided regardless of how caused; OR any decision made or action taken or not taken by any person in reliance upon any information or data furnished hereunder. LAST UPDATED JUNE 2013 ROAD NAME ROAD # RD WIDTH SECTION MILEAGE BEGIN END ACADEMY CIRCLE 584 14 SW 0.03 ACADAMY DRIVE ACADEMY DRIVE ACADEMY DRIVE 111 19 SW 0.75 REEVES STATION ROAD ACADEMY CIRCLE AIRPORT CIRCLE 592 18 NW 0.59 CLINES ROAD NORVILLE DRIVE ALEX COURT 20 SE 0.1 WILLOW HAVEN STREET CUL DE SAC ALLEN LOOP 54 18 SE 0.68 BOONE FORD ROAD BOONE FORD ROAD ALTON DRIVE 599 18 SE 0.15 PETERS STREET EAST FULLER STREET AMAKANATA ROAD 41 18 SE 1.00 DEWS POND ROAD DEAD END ANTHONY DRIVE 21 18 NE 0.12 MITCHELL STREET DEAD END APPLE GROVE LANE 716 20 SE 0.04 ORCHARD WAY CUL DE SAC APPLE ROAD 257 17 NE 1.42 U.S. -

Ford Road at I-275 Area Study Final Traffic and Environmental Study

M-153 (FORD ROAD) BU*AREA 7UDIILFDQG(QYLURQPHQWDO6WXG\ '*/"-REPORT April 2014 Prepared for: Prepared by: Michigan Department of Transportation &'0 6PLWK 0LFKLJDQ ,QFF ExecutiveSummary...................................................................................................................................................ESǦ1 Section1 Introduction.........................................................................................................................................1Ǧ1 Section2 ExistingConditions............................................................................................................................2Ǧ1 Section3 DataCollected......................................................................................................................................3Ǧ1 ͵ǤͳǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤ͵Ǧͳ ͵ǤʹǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤ͵Ǧͳ ͵Ǥ͵ ǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤ͵Ǧͳ ͵ǤͶ ǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤ͵Ǧʹ ͵ǤͷǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤǤ͵Ǧʹ -

An Assessment of Contaminants in UK Road-Verge Biomass and the Implications for Use As Anaerobic Digestion Feedstock

Waste and Biomass Valorization https://doi.org/10.1007/s12649-018-00557-x ORIGINAL PAPER An Assessment of Contaminants in UK Road-Verge Biomass and the Implications for Use as Anaerobic Digestion Feedstock Patrick E. Mason1 · Luke Higgins1 · Fernando Climent Barba1 · Adrian Cunliffe1 · Nick Cheffins2 · Douglas Robinson3 · Jenny M. Jones1 Received: 3 November 2018 / Accepted: 17 December 2018 © The Author(s) 2018 Abstract Biomass from harvested road-verge herbage has potential value as a feedstock for anaerobic digestion (AD) energy plants. However, the proximity to road traffic related pollution sources introduces the possibility of contamination by potentially toxic elements and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Potential sources of pollution from road traffic emissions are identi- fied and the consequent likelihood of certain contaminants being present at elevated levels is assessed. Samples of road verge biomass harvested from selected locations in Lincolnshire UK for use in AD plants were analysed to produce a set of measurements for the presence of the contaminants of interest. The measured levels of these contaminants are compared to reported background levels in UK herbage and soils to assess if there is significant increased concentration in road-verge biomass. Samples of digestate from an AD plant using the road-verge biomass as feedstock were also analysed to determine if there is notable risk of transfer and concentration of contaminants into agricultural land where the digestate may be used for fertilisation. While elevated levels of contaminants were detected, they were not found in concentrations on road verge biomass at high enough levels to cause adverse effects or concerns for its safe use as an AD feedstock. -

2015 Annual Report

ESPLANADE ASSOCIATION 2015 ANNUAL REPORT OUR MISSION The Esplanade Association was founded in 2001 in response to the deterioration in the state of the park and public outcry for improvements. Since our founding, we have been dedicated to making life better on the Esplanade. In support of its mission, the Esplanade Association strives to: • Revitalize and care for the park’s natural environment and historic character. • Restore and enhance the park’s amenities. • Improve the park visitors’ experience. • Offer a wide variety of free educational and recreational programming. • Advocate for public policy and resource allocation to support the park. Our mission is achieved in partnership with the Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation and in collaboration with the community that shares a vision and responsibility for the Esplanade. OUR VISION—A WORLD CLASS PARK: Through continued funding and advocacy it is our aspiration to not only maintain the Esplanade, but to transform it into a world class park. This will be achieved through leadership, financial support, management assistance, and advocacy. 1 OUR LEADERSHIP BOARD OF DIRECTORS OFFICERS Margo Levine Newman, Chair Fritz Casselman, Vice Chair Dan Capobianco, Treasurer TK Ankner, Clerk DIRECTORS Alexi Conine Ryan Jiminez David Solomon Jessica Crimmins Jeryl Oristaglio Sandy Steele Chris Egan Frank Panayotou Alicia Towns Franken Audrey Foster Tony Pangaro Emi Winterer Jim Foster Joan Patton Jody Gill Margaret Pokorny STAFF Tani Marinovich, Executive Director [email protected] -

578 Stream Crossing

578 - 1 NATURAL RESOURCES CONSERVATION SERVICE CONSERVATION PRACTICE STANDARD STREAM CROSSING (No.) CODE 578 DEFINITION areas of listed species. Avoid wetland areas. A stabilized area or structure constructed Discourage livestock loafing in the stream by across a stream to provide a travel way for locating crossings, where possible, out of people, livestock, equipment, or vehicles. shady riparian areas or by including gates in the design. PURPOSE Install stream crossings perpendicular to the • Provide access to another land unit direction of stream flow where possible. Fully consider the natural lateral migration pattern of • Improve water quality by reducing the stream in the design. Avoid skews on all sediment, nutrient, organic, and but the smallest streams. inorganic loading of the stream Access Roads. Where the stream crossing is • Reduce streambank and streambed installed as part of a roadway, size the erosion crossing according to NRCS Conservation Practice Standard, Access Road, Code 560. CONDITIONS WHERE PRACTICE APPLIES Width. Provide an adequate travel-way width This practice applies to all land uses where an for the intended use. Make “livestock- only” intermittent or perennial watercourse exists crossings no less than 6 feet wide and no and a ford, bridge, or culvert type crossing is more than 30 feet wide, as measured from the needed. upstream end to the downstream end of the stream crossing, not including the side slopes. CRITERIA Side Slopes. Make all side slope cuts and fills Apply this standard in accordance with all stable for the channel materials involved. Make local, State, Tribal, and Federal regulations, the side slopes of cuts or fills in soil materials including flood plain regulations and flowage no steeper than 2 horizontal to 1 vertical (2:1). -

Cost of Pavement Marking Materials

Synthesis Report 2000-11 Cost of Pavement Marking Materials Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. 2. 3. Recipient’s Accession No. 2000-11 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date COST OF PAVEMENT MARKING MATERIALS March 2000 6. 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Report No. David Montebello Jacqueline Schroeder 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Project/Task/Work Unit No. SRF Consulting Group, Inc. One Carlson Parkway North, Suite 150 11. Contract (C) or Grant (G) No. Minneapolis, MN 55447 12. Sponsoring Organization Name and Address 13. Type of Report and Period Covered Minnesota Department of Transportation Final Report 395 John Ireland Boulevard Mail Stop 330 St. Paul, Minnesota 55155 14. Sponsoring Agency Code 15. Supplementary Notes 16. Abstract (Limit: 200 words) Recent changes in laws regarding the use of volatile organic compounds will impact the type of pavement marking material that many communities use to mark/delineate their roads. This report presents information on the various types of pavement marking materials available. It is intended to provide readers with sufficient data to make educated decisions regarding the selection of an appropriate pavement marking material. The report pulls together information on pavement marking material terminology, the various types of pavement marking materials, their durability and their retroreflectivity. Changes in formulas relating to laws regulating the use of volatile organic compounds are explained, as well as the impacts of those changes. Additionally, there is a list of best management practices that can be implemented to enable an agency or community to get the most value for its money. -

Planning Highways for Industrial Development D Orothy A

Planning Highways for Industrial Development D orothy A. M uncy, A.I.P. City Planner and Industrial Planning Consultant Washington, D. C. Industry’s site standards have changed radically in the past decade. Land requirements have increased at a geometric rate. In the early postwar years, a ratio of three acres of land for one acre of building was thought spacious. Now a 10 to 1 ratio is not uncommon. Appearance of the surrounding area has become important. Until recently industry was resigned to “back of the track locations” in the slum end of town. Now management selects sites in neighborhoods that will not deteriorate into slums. Then, as a double insurance, the plan is encircled with acres of landscaping to protect the investment from the blight of future com mercial or industrial neighbors. But least expected among the changes is the strong desire of many industries to be “up front,” visible from the new highways and preferably one with controlled access. Thus added to transport economy are new advantages of a highway site—a promi nent and protected location. We cannot claim that the highway program will benefit equally all types of industry. Industries whose major cost is power, such as aluminum reduction, will continue to seek locations which provide cheap and plentiful power. Industries dependent upon the heavier forms of transportation—rail, water or air—will continue to rank these transport facilities above highways as location factors. Raw materials-oriented industries will continue to locate near the mines, the oil field, or the optimum point for cheap bulk transport. -

Statewide All Roads Layer Michigan Geographic Framework Field

Statewide All Roads Layer Michigan Geographic Framework Field Definitions (Shapefile Attribute Table) (June 1, 2014 – Version 14a) The following field definitions make up the shapefile attribute table called Statewide All Roads. This shapefile consists of all road segments in the Michigan Geographic Framework. This Statewide All Roads shapefile consists of the total of the road segments found in the Statewide. All road layers are also available by individual county. The attribute table can be found in the file Allroads_MI_v14a.DBF. Please Note : If you have any questions about the framework data you have received, please contact Josh Ross at the Center for Shared Solutions and Technology Partnerships. Phone: 517-373-7910, email: [email protected] Field Name Type Size Description Comments FCC C 3 Framework Classification Code See FCC Road Appendix at end of document. RDNAME C 60 This field contains a concatenated street For further information, see info on name made up of the data contained in FEDIRP, NAME, FETYPE, and FEDIRP, NAME, FETYPE, and FEDIRS FEDIRS below. FRADDL N 11 Left side from Address Potential “from” and “to” address TOADDL N 11 Left side to Address ranges. These ranges were originally transferred from TIGER. FRADDR N 11 Right side from Address Some modifications have since TOADDR N 11 Right side to Address been made. ZIPL N 5 Left side ZIP code ZIP codes as created by the Michigan Center for Geographic ZIPR N 5 Right side ZIP code Information based on US Postal Service data. These zip code fields may contain incomplete data at this time. A pre-directional associated with an FEDIRP C 2 Feature Prefix Direction arc’s street name (N, S, E, W, etc.). -

Gerald Ford It’S Personal

Gerald Ford It’s personal EPISODE TRANSCRIPT Listen to Presidential at http://wapo.st/presidential This transcript was run through an automated transcription service and then lightly edited for clarity. There may be typos or small discrepancies from the podcast audio. LILLIAN CUNNINGHAM: What's a memory from your dad's presidency that comes back to you often? One that, just for some reason, has stuck with you the most? STEVEN FORD: I have a funny story that's a great memory. It was the first time we had dinner in the White House. And you have to remember that we didn't get to move into the White House for seven days, because, when Nixon left, they weren't able to pack up all their belongings quick enough. Their daughter and son-in-law, I think, stayed and packed all their clothes. So, we had to go back to our little house in Alexandria, Virginia, and for the first seven days of dad's presidency, and I remember that first meal after Dad became president -- after he got sworn in that day, we're sitting around the dinner table, and my mother was cooking and my mother looked over at Dad. She was at the stove, and she goes, 'Jerry, something's wrong here. You just became president. And I'm still cooking.' And that was the memory that sticks out the most of what a strange time that was -- that, for seven days, we had to live in our little house in suburbia and Dad would commute to the Oval Office. -

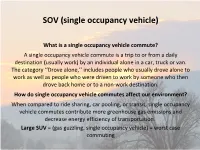

SOV (Single Occupancy Vehicle)

SOV (single occupancy vehicle) What is a single occupancy vehicle commute? A single occupancy vehicle commute is a trip to or from a daily destination (usually work) by an individual alone in a car, truck or van. The category ‘‘Drove alone,’’ includes people who usually drove alone to work as well as people who were driven to work by someone who then drove back home or to a non-work destination. How do single occupancy vehicle commutes affect our environment? When compared to ride sharing, car pooling, or transit, single occupancy vehicle commutes contribute more greenhouse gas emissions and decrease energy efficiency of transportation. Large SUV = (gas guzzling, single occupancy vehicle) = worst case commuting Why shouldn't people drive what they want? The importance of reducing larger vehicles which require greater fuel use becomes more evident as we try to reduce our carbon footprint. Road expansion and livable communities continue to emphasize fewer vehicles, thus the need for alternatives to SOV's and VMT's (vehicle miles traveled) but as everything tends to be incremental, just the choice of a smaller vehicle with a much lower carbon footprint would be an incremental victory for our environment. All politics is local and all choices are personal. If our citizens can make a positive personal choice, they will choose smaller vehicles with better fuel economy (30+ MPG) and encourage others to do the same. Positive vehicle choice is a step in the right direction. Top 10 Low Carbon Footprint Passenger Vehicles listed from lowest to highest in carbon footprint. 1. Toyota Prius 2. -

Recognition Distance and Elongation Ratio for Elongated Horizontal Pavement Markings: a Simulator Study

Recognition Distance and Elongation Ratio for Elongated Horizontal Pavement Markings: A Simulator Study Abstract All factors being equal, pavement marking signs are more likely to be detected by drivers than post-mounted signs. Several international manuals/guidelines explicitly state that elongation improves the legibility distance of pavement markings. Furthermore, some countries use greater elongation ratios on roadways with higher speed limits, while some others use a single elongation ratio regardless of the speed limit of the roadway. Therefore, research is needed to explore the relationship between speed and elongation ratio. Most of the available research on this topic has used stationary observers rather than subjects driving at posted roadway speeds, which makes a full-scale driving simulator an invaluable tool to study the effects of sign elongation on recognition distance while driving. Sixteen drivers, between the ages of 21 and 54, participated in the driving simulator study. Five elongation ratios that were tested in the driving simulator, 1:1, 1:2.5, 1:5, 1:7.5 and 1:10. The ‘Curve’ (W1-2) sign, ‘Speed Limit’ (R2-1) sign, and ‘Pedestrian Crossing’ (W11-2) sign were chosen for this research. Statistical analysis was performed to analyze the effect of elongation ratio on recognition distance through a random effects linear model. All variables were initially included and through the procedure it was found that age, gender, years of driving experience, and if the participant wore corrective lenses were not statistically significant covariates. It was found i that elongation ratio, sign type, and speed were statistically significant factors when perception response time is not taken into account.