Municipal Economic Review and Outlook 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Swartland Municipality Integrated Development Plan for 2017-2022

Swartland Municipality Integrated Development Plan for 2017-2022 THIRD AMENDMENT 28 MAY 2020 INTEGRATED DEVELOPMENT PLAN FOR 2017-2022 Compiled in terms of the Local Government: Municipal Systems Act, 2000 (Act 32 of 2000) Amendments approved by the Municipal Council on 28 May 2020 The Integrated Development Plan is the Municipality’s principal five year strategic plan that deals with the most critical development needs of the municipal area (external focus) as well as the most critical governance needs of the organisation (internal focus). The Integrated Development Plan – is adopted by the council within one year after a municipal election and remains in force for the council’s elected term (a period of five years); is drafted and reviewed annually in consultation with the local community as well as interested organs of state and other role players; guides and informs all planning and development, and all decisions with regard to planning, management and development; forms the framework and basis for the municipality’s medium term expenditure framework, annual budgets and performance management system; and seeks to promote integration by balancing the economic, ecological and social pillars of sustainability without compromising the institutional capacity required in the implementation, and by coordinating actions across sectors and spheres of government. AREA PLANS FOR 2020/2021 The five area plans, i.e. Swartland North (Moorreesburg and Koringberg), Swartland East (Riebeek West and Riebeek Kasteel), Swartland West (Darling and Yzerfontein), Swartland South (Abbotsdale, Chatsworth, Riverlands and Kalbaskraal) and Swartland Central (Malmesbury) help to ensure that the IDP is more targeted and relevant to addressing the priorities of all groups, including the most vulnerable. -

TKAK 2A?Sbo436 - 2&S00647

TKAK 2A?Sbo436 - 2&S00647 PEn-sfi DISCUSSION FORUM FOR RESEARCHERS IN NUCLEAR GEOLOGY- PROGRAMME ABSTRACTS AND NEWSLETTER PELINDABA REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA 1 -2 NOVEMBER 1984 by H J Brynard (Editor) NUCLEAR DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION OF SOUTH AFRICA (PTY) LTD x N U C O R m PRIVATE BAG X266 PRETORIA 0001 a, oo JANUARY 1985 Jill iltiitl PER-88 NUCLEAR DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION OF SOUTH AFRICA (PTY) LTD DISCUSSION FORUM FOR RESEARCHERS IN NUCLEAR GEOLOGY- PROGRAMME ABSTRACTS AND NESLETTER PELINDABA REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA 1 -2 NOVEMBER 1984 by H J Brynard* (Editor) 'Geology Department POSTAL ADDRESS: Private Bag X256 PELINDABA PRETORIA January 1985 0001 ISBN 0-86960-768-5 DISCUSSION FORUM FOR RESEARCHERS IN NUCLEAR GEOLOGY MAIN AUDITORIUM, PELINDABA 21 - 22 NOVEMBER 1984 PROGRAMME WEDNESDAY 21 NOVEMBER P D Toens -Welcome and introductor- remarks (NUCOR) SESSION 1: URANIUM IN GRANITES CONVENOR: A E SCHOCH (OOFS) P R Simpson Plenary address: Uraniferous high (British Geological heat production granites and their Survey) mineralising systems L J Robb The distribution of uranium in (E G R U) Archaean basement granites from the provenance region of the Witwatersrand Basin R J Hart Petrological and geochemical MAG Andreoli studies of the Vredefort Structure: (NUCOR) new clues to the evolution of the pre-Witwatersrand basement MAG Andreoli Radioelement fertilisation in R J Hart granulites of the Mozambique and (NUCOR) Kibaran belts N Niemand Uranium and thorium distribution in (NUCOR) the Verena and Makhutso gran, tes of the Bushveld Complex D Twist -

Provincial Gazette Provinsiale Koerant 6540 6540

PROVINCE OF WESTERN CAPE PROVINSIE WES-KAAP Provincial Gazette Provinsiale Koerant 6540 6540 Friday, 27 June 2008 Vrydag, 27 Junie 2008 Registered at the Post Offıce as a Newspaper As ’n Nuusblad by die Poskantoor Geregistreer CONTENTS INHOUD (*Reprints are obtainable at Room 9-06, Provincial Building, 4 Dorp Street, (*Herdrukke is verkrygbaar by Kamer 9-06, Provinsiale-gebou, Dorp- Cape Town 8001.) straat 4, Kaapstad 8001.) No. Page No. Bladsy Provincial Notices Provinsiale Kennisgewings 229 Bitou Municipality: Removal of restrictions...................... 1042 229 Bitou Munisipaliteit: Opheffing van beperkings ................ 1042 230 City of Cape Town (Cape Town Administration): Removal 230 Stad Kaapstad (Kaapstad Administrasie): Opheffing van of restrictions ...................................................................... 1042 beperkings ........................................................................... 1042 231 City of Cape Town (South Peninsula Administration): 231 Stad Kaapstad (Suidskiereiland Administrasie): Opheffing Removal of restrictions....................................................... 1042 van beperkings .................................................................... 1042 232 City of Cape Town (Tygerberg Administration): Removal 232 Stad Kaapstad (Tygerberg Administrasie): Opheffing van of restrictions ...................................................................... 1043 beperkings ........................................................................... 1043 233 Western Cape Gambling and -

Heritage Specialist Study for the Proposed Completion of the R45 Corridor, Malmesbury, Western Cape

HERITAGE SPECIALIST STUDY FOR THE PROPOSED COMPLETION OF THE R45 CORRIDOR, MALMESBURY, WESTERN CAPE (Assessment conducted under Section 38 (8) of the National Heritage Resources Act (No. 25 of 1999) as part of an EIA) Prepared for SRK Consulting (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd Private Bag X18 Rondebosch 7701 Tel: 021 659 3060 Email: [email protected] June 2014 Revised April 2015 Revised August 2015 Revised May 2016 Prepared by Natalie Kendrick Tim Hart ACO Associates Unit D17 Prime Park Mocke Rd Diep River Phone 0217064104 Fax 6037195 [email protected] 1 Contents 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 5 2 Methodology .................................................................................................................................. 6 2.1 Restrictions ............................................................................................................................ 7 3 Description of the affected environment. .................................................................................. 7 3.1 History of the affected area................................................................................................. 7 3.1.1 The cultural landscape ................................................................................................ 8 4 Findings. ........................................................................................................................................ 9 5 Assessment -

A Taxonomic Revision of the Genus Rafnia Thunb

A TAXONOMIC REVISION OF THE GENUS RAFNIA THUNB. (FABACEAE, CROTALARIEAE) by GAEL CAMPBELL DISSERTATION presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MAGISTER SCIENTIAE in BOTANY at the FACULTY OF NATURAL SCIENCES of the RAND AFRIKAANS UNIVERSITY SUPERVISOR: PROF. B-E. VAN WYK OCTOBER 1998 In some cases we learn more by looking for the answer to a question and not finding it than we do from learning the answer itself. Dallben, from The Book of Three by Lloyd Alexander (1988). TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY OPSOMMING iii CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 2 MATERIAL AND METHODS 2 CHAPTER 3 VEGETATIVE MORPHOLOGY 21 3.1 Habit 21 3.2 Fire-survival strategy 25 3.3 Mode of flowering 26 3.4 Leaves 27 3.4.1 Leaf morphology 27 3.4.2 Stomata 34 3.4.3 Midrib anatomy 35 CHAPTER 4 REPRODUCTIVE MORPHOLOGY 37 4.1 Inflorescence 37 4.1.1 Inflorescence structure 37 4.1.2 Peduncle anatomy 42 4.2 Flowers 43 4.2.1 Bract and bracteoles 49 4.2.2 Calyx 51 4.2.3 Standard petal 60 4.2.4 Wing petals 64 4.2.5 Keel petals 67 4.2.6 Stamens 72 4.2.7 Pollen 77 4.2.8 Pistil 79 4.3 Pods 81 4.4 Seeds 86 CHAPTER 5 OTHER EVIDENCE 96 5.1 Introduction 96 5.2 Distribution and geographical patterns 96 5.3 Flowering and fruiting phenology 102 5.4 Chromosome cytology 105 5.5 Secondary metabolites 106 5.5.1 Alkaloids 106 5.5.2 Flavonoids 107 5.6 Enzymes 110 5.7 Conclusions 113 CHAPTER 6 PHENETIC ANALYSIS 114 CHAPTER 7 CLADISTIC ANALYSIS 120 CHAPTER 8 CONCLUSIONS 127 CHAPTER 9 TAXONOMY OF THE GENUS RAFNIA 128 9.1 Generic position within the family 128 9.2 Historical overview of the taxonomy of Rafnia 129 9.3 The genus Rafnia Thunb. -

“Stinky and Smelly – but Profitable”: the Cape Guano

“STINKY AND SMELLY – BUT PROFITABLE”: THE CAPE GUANO TRADE, c.1843 – 1910 HENDRIK SNYDERS DISSERTATION PRESENTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (HISTORY) IN THE FACULTY OF ARTS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES AT STELLENBOSCH UNIVERSITY PROMOTOR: PROFESSOR SANDRA S. SWART CO-PROMOTOR: PROFESSOR ALBERT. M. GRUNDLINGH DECEMBER 2011 1 University of Stellenbosch http://scholar.sun.ac.za DECLARATION By submitting this dissertation electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualifications. SIGNATURE:……………………………….. DATE:………………………………………… Copyright©2011 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved 2 University of Stellenbosch http://scholar.sun.ac.za ABSTRACT Soil infertility and concomitant low levels of food security under conditions of population pressure and land scarcity have been, and still remain, one of society’s most daunting challenges. Over time, societies have tried to maximize the yield from the available land through the use of various fertilisers. In the 19th century in the midst of an environment infertility crisis, guano (bird dung) from the Peruvian coastal islands became, through a combination of factors, the international fertilizer of choice for most commercial farmers. As a result, a combination of natural factors, monopoly control and price manipulation contributed to the relative scarcity of the product. Nevertheless, strategic manoeuvring between the major players prevented any significant change in the supply regime. -

Swartland Municipality AMENDMENTS to THE

Swartland Municipality AMENDMENTS TO THE INTEGRATED DEVELOPMENT PLAN FOR 2017-2022 DRAFT - March 2020 Sections that are amended Section Page Forewords 1 . Executive Mayor, Tijmen van Essen [Update] 1 . Municipal Manager, Joggie Scholtz [Update] 2 Chapter 1: Introduction 5 1.6 The IDP and Area Plans [Amend ward priorities] 5 Chapter 2: Context 7 2.1 Swartland municipal area at a glance [Update with figures from the 2019 SEP report] 7 Chapter 3: The planning process 8 3.4 Annual process followed between August 2019 and May 2020 [Amend] 8 Chapter 4: The Organisation 8 4.2 The council and council committees [Add new proportional councillor] 8 Chapter 5: International, national and provincial policy directives 8 5.2 National policy directives 8 (b) Medium-Term Strategic Framework (MTSF): 2019 - 2024 [Add in the place of the old MTSF] (c) National District-based approach [Add] (d) Back to basics programme - September 2014 [Delete] 5.3 Provincial policy directives 8 (a) Provincial Strategic Plan 2019-2024 [Add in the place of the WC Provincial Strategic Plan 2014-2019] (b) Western Cape Joint District Approach [Add] (c) Growth potential of towns study 2018 (Swartland info) [Add] Chapter 6: District and Local Municipal level policy directives [Add the words "District and Local" to the heading] 10 6.1 Links between National, Provincial and local policy directives [Add] 6.2 West Coast District Single Implementation Plan [Add] 10 Chapter 7: The strategy unpacked 28 7.4 The Municipality's five year strategy [Update and amend] 29 Chapter 8: Financial -

Section B, Chapter 18

SectionSection B: B: Profile National Western and DistrictCape Province Profiles 18 Western Cape Province Cape Town Metropolitan Municipality (CPT) The City of Cape Town Metropolitan municipality is situated on the southern peninsula of the Western Cape Province.a The City of Cape Town Metropolitan Municipality incorporates eight health sub-districts, namely: Cape Town Eastern, Cape Town Northern, Cape Town Southern, Cape Town Western, Khayelitsha, Klipfontein, Mitchell’s Plain and Tygerberg. Cities/Towns: Athlone, Atlantis, Belhar, Bellville, Blackheath, Blouberg, Blue Downs, Brackenfell, Cape Point, Cape Town, Delft, Durbanville, Elsies Rivier, Fish Hoek, Goodwood, Gordon’s Bay, Grassy Park, Guguletu, Hout Bay, Khayelitsha, Kommetjie, Kraaifontein, Kuils River, Langa, Macassar, Matroosfontein, Melkbosstrand, Milnerton, Mitchells Plain, Muizenberg, Noordhoek, Nyanga, Parow, Philadelphia, Philippi, Robben Island, Scarborough, Simon’s Town, Sir Lowry’s Pass, Somerset West, Southern Suburbs, Strand, Table View Area: 2 446km² Population (2019)b: 4 194 178 DistrictDistrict % percentagepopulation by ag epopulation-gender group cbyom page-genderared to South Af rgroupica compared to South Africa WC, Cape Town MM (CPT) 2000/01 2010/11 2020/21 South Africa % of total population [Male | Female] - lines South Africa % of total population [Male | Female] - lines South Africa % of total population [Male | Female] - lines AgeGrp 8% 6% 4% 2% 0% 2% 4% 6% 8% 8% 6% 4% 2% 0% 2% 4% 6% 8% 8% 6% 4% 2% 0% 2% 4% 6% 8% 65+ 2.0% 3.0% 2.1% 3.1% 2.8% 4.0% 60-64 -

Local Library

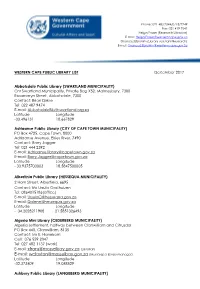

Phone: 021 483 2044/0718/2249 Fax: 021 419 7541 Helga Fraser (Research Librarian) E-mail: [email protected] Shanaaz Ebrahim (Library Assistant Research) E-mail: [email protected] WESTERN CAPE PUBLIC LIBRARY LIST December 2017 Abbotsdale Public Library (SWARTLAND MUNICIPALITY) Cnr Swartland Municipality, Private Bag X52, Malmesbury, 7300 Roosmaryn Street, Abbotsdale, 7300 Contact: Brian Dirkse Tel: 022 487 9474 E-mail: [email protected] Latitude Longitude -33.496131 18.667829 Adriaanse Public Library (CITY OF CAPE TOWN MUNICIPALITY) PO Box 4725, Cape Town, 8000 Adriaanse Avenue, Elsies River, 7490 Contact: Barry Jagger Tel: 021 444 2392 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Latitude Longitude - 33.9375700003 18.5847500005 Albertinia Public Library (HESSEQUA MUNICIPALITY) 2 Horn Street, Albertinia, 6695 Contact: Ms Ursula Oosthuizen Tel: 0864015186(office) E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Latitude Longitude - 34.2028211908 21.5851326493 Algeria Mini Library (CEDERBERG MUNICIPALITY) Algeria settlement, halfway between Clanwilliam and Citrusdal PO Box 440, Clanwilliam, 8135 Contact: Ms E. Hanekom Cell: 076 559 2347 Tel: 027 482 1137 (work) E-mail: [email protected] (Librarian) E-mail: [email protected] (Municiapal library manager) Latitude Longitude -32.373509 19.058529 Ashbury Public Library (LANGEBERG MUNICIPALITY) 1 52 Wilge Ave, Ashbury Private Bag X2, Ashton, 6715 Cnr Eike and Wilge Avenue, Ashbury, Montagu -

1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background a Five

P a g e | 1 1. INTRODUCTION • complies with the policies of national legislation and policy frameworks concerned with housing and the Western Cape Human Settlement Plan; 1.1 Background • forms part of and complies with the SDF and the IDP and be integrated A five year Housing Master Plan was compiled for the Saldanha Bay with other sectorial plans (i.e. water services, etc.); Municipality in 2009 and a 5-year housing pipeline was compiled for the period • co-ordinates and facilitates alignment between provincial and district 2012-2017. It is the intention to update and replace these documents with an housing strategies, policies, delivery systems and other related initiatives; integrated Human Settlements Plan (HSP) and a 10-year concept housing • integrates with the West Coast District Municipality HSP; pipeline. • establishes a medium to long-term (10 year) human settlement delivery plan; The Saldanha Bay Municipality’s Integrated Development Plan (IDP) and • responds to the current and future housing needs, as well as other related Spatial Development Framework (SDF) contain strategies which aim to challenges faced within the municipal area; eliminate the current housing backlog, to provide subsidised housing in • identifies the strategic housing priorities within the municipal area; appropriate locations and provide housing for all income groups. In this • inform the need of socio-economic facilities and the desired location of manner, integrated and sustainable settlements can be created. such facilities within the human settlement; • assists with the preparation of Council’s annual budgets for housing and The Saldanha Bay Municipality IDP has identified land for housing as one of its related expenditure; key capital and operational priority needs. -

1 July 2019 Prepared for & Five Local

INTEGRATED SECOND GENERATION OF THE WEST COAST DISTSRIC MUNICIPALITY INCLUSIVE OF FIVE LOCAL MUNICIPALITIES AIR QUALITY MANAGEMENT PLAN, 2019-2024 July 2019 Prepared for & Five local municipalities Compiled by: Liketso Tsotetsi Reviewed by: Dr Brett Kuyper 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY INTRODUCTION Air pollution is a growing concern across South Africa as a result of ongoing industrialization. The continuous increase of industrial development is important for economic growth, however emissions can be harmful to human health and the environment. It is therefore necessary to regulate industrial emissions that affect air quality. The National Environmental Management: Air Quality Act (39) of 2004 and Air Quality Management Plans (AQMP) are the primary tools used by National and Provincial Government and Municipalities to regulate air quality. There is growing understanding of the relationship between the air quality and climate change highlighting the importance of interlinking the two issues in terms of management in order to achieve clean and safe environment. The developmental framework used in the second generation AQMP was based on the Department of Environmental Affairs (DEA) Manual for Air Quality Management Planning (2012). The AQMP considered the vision and mission statements of the West Coast District Municipality (WCDM) LEGISLATION The National Environmental Management: Air Quality Act 39 of 2004 (NEM: AQA) replaced the repealed Atmospheric Pollution Prevention Act 45 of 1965 (APPA) in South Africa. National government has implemented NEM: AQA through a number of regulations and policies. This second generation AQMP aims to meet these national policies. Furthermore, the AQMP makes provision for climate change mitigation measures and adaptive strategies as part of inherent strategies and intervention plans. -

Curriculum Vitae – Nicolaas Willem Hanekom

CURRICULUM VITAE – NICOLAAS WILLEM HANEKOM Profession: Environmental Scientist and Environmental Assessment Practitioner Date of Birth: 02/02/1967 BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH Nicolaas Hanekom is a qualified Environmental Assessment Practitioner (”EAP”) who holds a Masters Technologiae, Nature Conservation (“Vegetation Ecology and Biodiversity Assessment”) degree from the Cape Peninsula University of Technology. Nicolaas is certified in terms of section 20(3)(a) of the Natural Scientific Professions Act, 2003 (Act 27 of 2003), as a Professional Natural Scientist (Ecological Science) Registration Number: 4008274/11. He further qualified in Environmental Management Systems ISO 14001:2004, at the Centre for Environmental Management, North-West University, as well as Environmental Management Systems ISO 14001:2004 Audit: Internal Auditors Course to ISO 19011:2003 level, from the Centre for Environmental Management, North-West University qualifying him to execute audits to ISO/SANS environmental compliance and EMS standards. He has also completed the suite of Greener Governance courses with certificates in; • An Overview of Environmental Management at the Local Government Level, Centre for Environmental Management, North-West University; • Greener Governance for Local Authorities, Centre for Environmental Management, North- West University; • Tools for Integrated Environmental Management and Governance, Centre for Environmental Management, North-West University. He further attended and obtained a certificate on Integrated Protected Area Planning at the Centre for Environmental Development, University of Kwa Zulu Natal and a certificate in Project Management (Theory and Practical), through CS Holdings. Nicolaas has lectured in two subjects at the Cape Peninsula University of Technology. He has 26 years of environmental planning experience, working for Free State and Western Cape departments of environmental affairs, where he reviewed and commented on development (EIA) applications, in the West Coast Region.