Final Exams: Pavlov's Dogs, Father Guido, Pinball

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Creative Life of 'Saturday Night Live' Which Season Was the Most Original? and Does It Matter?

THE PAGES A sampling of the obsessive pop-culture coverage you’ll find at vulture.com ost snl viewers have no doubt THE CREATIVE LIFE OF ‘SATURDAY experienced Repetitive-Sketch Syndrome—that uncanny feeling NIGHT LIVE’ WHICH Mthat you’re watching a character or setup you’ve seen a zillion times SEASON WAS THE MOST ORIGINAL? before. As each new season unfolds, the AND DOES IT MATTER? sense of déjà vu progresses from being by john sellers 73.9% most percentage of inspired (A) original sketches season! (D) 06 (B) (G) 62.0% (F) (E) (H) (C) 01 1980–81 55.8% SEASON OF: Rocket Report, Vicki the Valley 51.9% (I) Girl. ANALYSIS: Enter 12 51.3% new producer Jean Doumanian, exit every 08 Conehead, Nerd, and 16 1975–76 sign of humor. The least- 1986–87 SEASON OF: Samurai, repetitive season ever, it SEASON OF: Church Killer Bees. ANALYSIS: taught us that if the only Lady, The Liar. Groundbreaking? breakout recurring ANALYSIS: Michaels Absolutely. Hilarious? returned in season 11, 1990–91 character is an unfunny 1982–83 Quite often. But man-child named Paulie dumped Billy Crystal SEASON OF: Wayne’s SEASON OF: Mr. Robinson’s unbridled nostalgia for Herman, you’ve got and Martin Short, and Neighborhood, The World, Hans and Franz. SNL’s debut season— problems that can only rebuilt with SNL’s ANALYSIS: Even though Whiners. ANALYSIS: Using the second-least- be fixed by, well, more broadest ensemble yet. seasons 4 and 6 as this is one of the most repetitive ever—must 32.0% Eddie Murphy. -

Permission Granted for Weddings at Church of Our Lady of Loretto

Ax murders - page 3 Enthusiastic students check out lower prices at new store s opening By MARK S. PANKOWSKI tive to the bookstore,” said New s S ta ff Cavanaugh senior Joe Pangilinan. “ I see these notebooks here The N otre Dame Student Saver cheaper than they were in the the Store opened its doors yesterday to bookstore,” said John Gardiner, a an enthusiastic crow d o f students on Stanford sophomore. “It’s good to the second floor of LaFortune Stu see that the Student G overnm ent is dent Center. offering a viable service for the stu Comments about the new store dents.” ranged from “ it’s a good idea ” to “ it ’s Most of the negative comments the greatest supersaver ever as made were complaints about the sembled by a human being.” lack of college-ruled notebooks and The student store manager, Rick health and beauty items. Schimpf Schimpf, was very happy with the hopes to remedy those problems in response of the student body. the com ing days. “ We had 15 to 20 people standing "I’m working with our distributor outside before we even opened, ” to make sure the health and beauty said Schimpf. “We made $450 the aids w ill be in tomorrow (Jan. 18) - first hour,” he said, adding, Monday at the latest. ” “ Business is fantastic.” Regarding the college ruled Most people who came into the notebooks, Schimpf said, “In the Student Saver were there for one report given by the committee, they reason: to save money. see "This is definitely a better alterna STORE, page 6 Ethiopia blocked aid, U.S. -

Farley Resume 2013

William N. Farley EDUCATION 1971 M.F.A. California College of Arts and Crafts, Oakland, California. major: Sculpture; minor: Filmmaking. 1969 B.F.A. Maryland Institute College of Art, Baltimore, Maryland. major: Sculpture. 1968 Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, Skowhegan, Maine. 1961-64 Vesper George School of Art, Boston, Massachusetts. PHOTOGRAPHY EXHIBITIONS 2013 SFMoMA Artist Gallery, Fort Mason, CA 2011 Outlandish, Contemporary Depictions of Nature, Bedford Gallery, Walnut Creek, CA 2011 LandsCApes: Glimpses of Everyday California, de Saisset Museum, Santa Clara, CA FILM EXHIBITIONS Shadow & Light, The Life and Art of Elaine Badgley Arnoux 2009 Ventura Film Festival, Ventura, California. 2009 Mendocino Film Festival, Mendocino, California. 2009 Mill Valley Film Festival, Mill Valley, California. 2009 Santa Fe Film Festival, Santa Fe, New Mexico. Walt Whitman’s Song Of Myself 2008 Mendocino Film Festival, Mendocino, California. 2008 FIAAP 08 Festival Internacional Audiovisual de Artes Performativas Museu Nacional do Teatro Lisboa, Portugal. Darryl Henriques Is In Show Business 2007 Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, San Francisco, California. 2006 Mendocino Film Festival, Mendocino, California. 2006 Mill Valley Film Festival, Mill Valley, California. Arianna’s Journey 2007 Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, San Francisco, California. The Stories 2007 Mendocino Film Festival, Mendocino, California. 2007 Rhode Island International Film Festival, Providence, Rhode Island. 2007 Cleveland Cinematheque, Cleveland, Ohio. 2006 Mill Valley Film Festival, Mill Valley, California. 2006 Southern Exposure Mayhem Film Festival, San Francisco, California. The Old Spaghetti Factory 2009 Cinema By The Bay, San Francisco International Film Festival, San Francisco, California. 2001 PBS national broadcast, 90 cities in the U.S. -

THE COWL True, Not True Because PROVIDENCE It’S Here.” COLLEGE Volume XXXII,No

“ It’s here because it's THE COWL true, not true because PROVIDENCE it’s here.” COLLEGE Volume XXXII,No. 19 March 26,1980 Providence, R.I. 02918 USPS 136-260 12 Pages PC feels the pinch Tuition, fees, room, board affected the cost of tuition and room and the student activity fee by $10. board. Bill Pearson, president of the Tuition, Tuition, for the 1980-1981 Student Congress, issued a letter school year, will be increased by last week announcing the increase, $600 for the year. The cost of which will ultimately benefit the board living on campus will be raised a entire college community. total of $240 for the entire year. The higher fee would “ increase In regard to the recently base appropriations to clubs and hike$840 announced increase. Father Peter organizations,” allowing for By Karen Ryder son stated, “ I realize that these quality entertainment to continue additional costs are significant, to be offered at the school. Rev. Thomas R. Peterson, but they are needed if we are to Pearson also cited the proposed maintain a balanced budget, O.P., president of “Providence raise in the drinking age as which is the only genuine basis of College, has announced yet another reason for the additional fiscal stability. Investigation will another increase in the cost of $10. Because many organizations show that these increases are quite Manning captures attending PC. depend on mixers and the like to similar, and in some instances The skyrocketing cost of raise funds, profits of such activi- much less, than those of compar energy, rapidly rising inflation, ties would be seriously inhibited and the state of the economy, able academic institutions. -

Final Final Front Pcf Program

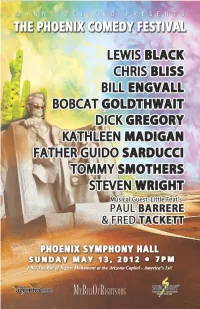

Wishes to give special Gratefully acknowledges major acknowledgement to support for this event from This project would not Building Integrity Since 1890 have been possible without their ongoing support Proud to Honor the Tenets of Our Freedom Gratefully acknowledges major Gratefully acknowledges major support for this event from support for this event from find your inspiration 5700 East McDonald Drive Scottsdale, Arizona 85253 Reservation: 480-948-2100 www.sanctuaryaz.com The Artists The Artists Lewis Black Kathleen Madigan George Carlin, Larry King and Jules Feiffer love Lewis In her 22 year career, Kathleen Madigan has never been Black. They love him because his insights and love/hate hotter. With her recent Showtime special, “Gone relationship with America are brilliantly expressed in his Madigan,” in constant rotation and the DVD-CD of the concerts and TV appearances worldwide. How can you special topping the Amazon and iTunes charts, Madigan not love a man who says, “Republicans are a party with has the entire year booked with over 100 theater gigs bad ideas and Democrats are a party with no ideas.” Will across the country and numerous television appearances. Rogers would have been proud. Bill Engvall Father Guido Sarducci (Don Novello) It’s Bill Engvall’s ability for sharing the humor in Don Novello is a writer, film director, producer, actor, everyday situations that has made him one of the top and comedian, best known for his many appearances as comedians today. Best known for as part of the Father Guido Sarducci on “Saturday Night Live”, a role enormously successful Blue Collar Comedy Tour, Bill’s he reprised most recently on “The Colbert Report.” His also starred in his own self-titled sitcom for TBS, had books of replies by the famous and powerful to letters he numerous television specials and film appearances, and is wrote as another of his creations, Lazlo Toth, remain currently headlining his own solo comedy tour. -

South East West Midwest

NC State (12) Arizona St. (10) Kansas St. (9) Kentucky (8) Texas (7) Massachusetts (6) Saint Louis (5) Louisville (4) Duke (3) Michigan (2) Wichita St. (1) Florida (1) Kansas (2) Syracuse (3) UCLA (4) VCU (5) Ohio St. (6) New Mexico (7) Colorado (8) Pittsburgh (9) Stanford (10) 1. Zach Galifianakis, 1. Jimmy Kimmel, 1. Eric Stonestreet, 1. Ashley Judd, 1. Walter Cronkite, 1. Bill Cosby, 1. Enrique Bolaños, 1. Diane Sawyer, 1. Richard Nixon, 37th 1. Gerald Ford, 38th 1. Riley Pitts, Medal 1. Marco Rubio, U.S. 1. Alf Landon, former 1. Ted Koppel, TV 1. Jim Morrison, 1. Patch Adams, 1. Dwight Yoakam, 1. Penny Marshall, 1. Robert Redford, 1. Gene Kelly, 1. Herbert Hoover, actor, "The Hangover" host, "Jimmy Kimmel actor, "Modern Family" actress, "Kiss the Girls" former anchorman, actor/comedian, "The former president of news anchor President of the U.S. President of the U.S. of Honor recipient Senator, Florida Kansas governor, 1936 journalist, "Nightline" musician, The Doors doctor/social activist country music director/producer, "A actor, “Butch Cassidy actor/dancer/singer, 31st President of the 2. John Tesh, TV Live!" 2. Kirstie Alley, 2. Mitch McConnell, CBS Evening News Cosby Show" Nicaragua 2. Sue Grafton, 2. Charlie Rose, 2. James Earl Jones, 2. Shirley Knight, 2. Bob Graham, presidential candidate 2. Dick Clark, 2. Francis Ford 2. Debbie singer-songwriter League of Their Own" and the Sundance Kid” "Singin' in the Rain" U.S. composer 2. Kate Spade, actress, "Cheers" U.S. Senator, Kentucky 2. Matthew 2. Richard Gere, actor, 2. Robert Guillaume, author, “A is for Alibi” talk-show host, actor, "The Great actress, "The Dark at former U.S. -

The Fake News: Examining the Image of the Journalist Through Weekend Update (Part I: 1975-1980)

Lawrence Murray 2013-2014 J576 The Fake News: Examining the Image of the Journalist Through Weekend Update (Part I: 1975-1980) The Fake News: Examining the Image of the Journalist Through Weekend Update (Part I: 1975-1980) By Lawrence Murray 1 Lawrence Murray 2013-2014 J576 The Fake News: Examining the Image of the Journalist Through Weekend Update (Part I: 1975-1980) ABSTRACT The image of the broadcast news journalist is one that we can identify with on a regular basis. We see the news as an opportunity to be engaged in the world at large. Saturday Night Live’s “Weekend Update” brought a different take on the image of the journalist: one that was a satire on its head, but a criticism of news culture as a whole. This article looks at the first five seasons of Saturday Night Live’s “Weekend Update” and the image of the journalist portrayed by the SNL cast members serving as cast members from 1975 (Chevy Chase) until 1980 (Bill Murray and Jane Curtin). This article will show how the anchors’ style and substance does more than tell jokes about the news. The image of the journalist portrayed through the 1970s version of “Weekend Update” is mostly a negative one; while it acknowledges the importance of news and information by being a staple of the show, it ultimately mocks the news and the journalists who are prominently featured on the news. 2 Lawrence Murray 2013-2014 J576 The Fake News: Examining the Image of the Journalist Through Weekend Update (Part I: 1975-1980) INTRODUCTION: WEEKEND UPDATE Saturday Night Live is a sketch comedy show that debuted on NBC in 1975. -

1980 Brown and Gold Vol XII No 18 March 26, 1980

Regis University ePublications at Regis University Brown and Gold Archives and Special Collections 3-26-1980 1980 Brown and Gold Vol XII No 18 March 26, 1980 Follow this and additional works at: https://epublications.regis.edu/brownandgold Part of the Catholic Studies Commons, and the Education Commons Recommended Citation "1980 Brown and Gold Vol XII No 18 March 26, 1980" (1980). Brown and Gold. 482. https://epublications.regis.edu/brownandgold/482 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Archives and Special Collections at ePublications at Regis University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Brown and Gold by an authorized administrator of ePublications at Regis University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. {' G.A. Meeting Tonight GOld) at 5:30 p.m. in the Lib.rary Regis College. Volume XII Wednesday, March 26, 1980 Number 18 New R.A. ,s Selected Dr. Ozog Honored As For Fall Faculty -Lecturer Of The Year lifestyles, and commitment to By Maureen Corbley residence hall living. by Gail Gassman The Office of Student Life has The A.A.'s main duties are to announced the selection of the Dr. Francis Ozog, of the act as Counselor by being chemistry department of Re new A.A.'s for the Fall 1980 avaliable to advise students semester. They are: Lisa Are gis, has been named Regis Col llano, Diane Coglan, Libby concerning personal problems; lege Faculty Lecturer of the Dale, Julie Griffin, Jim Haed coordinator by initiating year for 1980. Dr. Ozog has rich, Ed Haran, Shelly Hee, programs for the hall; Adminis been a part of the faculty for 30 Jane Hollman, Tom Kearney, trator by handling paperwork years and feels highly honored Mike Lingg, Chris McGrath, and attending meetings neces to have been given the award. -

“America's Most Famous Catholic” (According to Himself): Stephen

Brehm NARW 9.28.18 Hello NARWers, Thank you so much for reading the introduction and appendix/methodology section of my manuscript. Some background: I am transitioning my work from a dissertation into a book for Fordham University Press. The revised manuscript is due to the press January 31, 2019 (a timeline of events is attached). My reviewers main concern was that the introduction was too dissertation-y (not a surprise as it was a dissertation). So I have done my best to simplify the introduction, remove extraneous footnotes, and refocus sections. I have amped up (slightly) the Catholic component and toned down the humor & religion angle. I have reorganized the entire introduction and separated out the methodology section to an appendix. My questions for you: how is the new intro? Where can I punch it up and where is it confusing? I also have no idea how to start a book. What should the introductory sentences look like? Should I start with a story? What story? Should I begin with an introduction to Colbert himself or dive into my argument? Should I use another distinction between actor and character other than Colbert and COLBERT? More logistical questions: will the book suffer if I don’t have many photos? How should I go about obtaining rights to images I’ve screenshot? What should the cover be? I’m considering commissioning a friend to create a stained glass image of Colbert with ashes on his forehead in front of The Colbert Report stained glass. What covers have been evocative for you? Do you know other people I should be consulting about this? Thank you for your advice and guidance as I revise this manuscript. -

Actuary of the Future May 2008

May 2008 • Issue No. 24 ACTU A RY OF THE FUTURE Published by the Society of Actuaries, Schaumburg, Illinois Pushing the Boundaries: Actuaries without Frontiers by Pritesh Modi CONTENTS P 1. Pushing the Boundaries: Actuaries without Frontiers by Pritesh Modi 2. Chairperson’s Corner: Live from New York by Susan Sames 5. A Student’s View of the Networking Session Held by the Younger Actuaries Network at Baruch College by Chun Gong 6. “Breaking Away from the Curve: How to Excel Beyond Exams” Webcast 7. Expanding the Demand for Actuaries – The CERA Research Initiative ow does the task of assisting with the development of a mortality study sound by Frank Sabatini to you? Not very exciting, is it? Well, how about going away to Almaty to construct one? It is the capital city of Kazakhstan—even my spellchecker doesn’t 8. Research on Unmet Needs for recognize it, so don’t beat yourself up if you haven’t heard of it! How about implementing Financial Advice H by Paul Richmond a crop insurance program in Malawi? Or assisting a French NGO with the implementa- tion of a health benefits coverage program for an impoverished mutual benefit society in 1.0. Update from the Younger Actuaries India? If these assignments pique your interest, then read on….. Network by Joanna Chu In order to book your ticket to Almaty, your first step would be to become a member of the Actuaries without Frontiers (AWF) organization. The AWF was established 1.1. Be an Actuary of the Future by in Berlin in November 2003 as a nonprofit organization under the auspices of the Attending a Session at the SOA Spring Meetings International Actuarial Association, in cooperation with various national actuarial orga- nizations. -

A History of Television News Parody and Its Entry Into the Journalistic Field

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Communication Dissertations Department of Communication Summer 8-13-2013 Nothing But the Truthiness: A History of Television News Parody and its Entry into the Journalistic Field Curt W. Hersey Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/communication_diss Recommended Citation Hersey, Curt W., "Nothing But the Truthiness: A History of Television News Parody and its Entry into the Journalistic Field." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2013. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/communication_diss/46 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Communication at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Communication Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NOTHING BUT THE TRUTHINESS: A HISTORY OF TELEVISION NEWS PARODY AND ITS ENTRY INTO THE JOURNALISTIC FIELD by CURT HERSEY Under the Direction of Ted Friedman ABSTRACT The relationship between humor and politics has been a frequently discussed issue for communication researchers in the new millennium. The rise and success of shows like The Daily Show and The Colbert Report force a reevaluation of the relationship between journalism and politics. Through archival research of scripts, programs, and surrounding discourses this dissertation looks to the past and historicizes news parody as a distinct genre on American television. Since the 1960s several programs on network and cable parodied mainstream newscasts and newsmakers. More recent eXamples of this genre circulate within the same discursive field as traditional television news, thereby functioning both as news in their own right and as a corrective to traditional journalism grounded in practices of objectivity. -

A Touch of Scandal Pdf, Epub, Ebook

A TOUCH OF SCANDAL PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Jennifer Haymore | 416 pages | 01 Apr 2010 | Time Warner Trade Publishing | 9780446540278 | English | New York, United States A Touch of Scandal PDF Book Investigating on her own, Katherine's suspects to the idenity of the blackmailer are: a shadowy power broker, a charismatic minister, an activist priest, or even her own husband. Full Cast and Crew. In , Friedman, Billings, Ramsey, as well as Friedman and two other former executives, settled insider trading and other charges with the SEC over a private investment in public equity deal involving CompuDyne Corp. Writer: Richard A. Petraeus pleaded guilty to one misdemeanor count of mishandling classified information. Michael will be pleased for certain. Exiled from her familial estate for "scandalous indiscretions," amorous Austrian Princess Olympia Sophia Loren turns her attentions to a handsome American stranger John Gavin and finds that the attraction is mutual And now that day had come… Illustration by Michael Johnson for Woman, Was it her own beauty that led him on, or was it her disturbing resemblance to someone else… Illustration by Joe Bowler for The Saturday Evening Post, When a woman wishes to go back in time, it is for a man she seeks to meet again… Illustration by Coby Whitmore for Good Housekeeping, Time was running away, faster, faster. Size 5. Alternate Versions. Looking for something to watch? There are books with recipes from different ethnic groups and geographic areas including Himalayan Mountain Cookery , The Art of Caribbean Cookery, and Rattlesnake Under Glass: a Roundup of Authentic Western Recipes, which contains this actual recipe for rattlesnake, yum! SOME films seem to proceed on the premise that, given a juicy core, the audience will buy anything.