Case 2:12-Cv-04103-AB Document 42 Filed 05/21/13 Page 1 of 17

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stericycle Products 2012

INFECTION CONTROL PRODUCT CATALOG sWWWSTERICYCLECOM • • •e•e Ster1cyc. Ie· • • • Protecting People. Reducing Dear Valued Customer, We invite you to take a look at the largest selection of waste disposal programs, containment solutions, patient care and infection control products available. Knowing that you have countless choices for purchasing your supplies, I can say with conviction that we strive to make Stericycle your first and only choice. Our team is here to help you select the right products and solutions for managing your medical waste disposal and ensuring that your business is compliant and your employees are kept safe. Protecting People. Reducing Risk. These are more than just words in our company tagline — they are the primary focus for us at Stericycle. We have the important responsibility of helping people enjoy healthier lives in the safety of their workplace. Our number one goal is to provide superior customer service while going that extra mile to help you promote safety and compliance. Thank you for your continued business. It is a privilege to serve you. Sincerely, Jennifer Koenig Vice President, Healthcare Compliance Stericycle, Inc. We've Got You Covered. Drug Disposal Service SterisSafe OSHA Compliance Program Sharps Disposal Management The environmentally safe way Training, consulting, site audits — everything you Expert collection and processing to dispose of pharmaceutical need to keep your staff safe and achieve compliance. that reduces the risk of needlesticks waste, including expired and is environmentally friendly. drug samples. 800.355.8773 www.stericycle.com TABLE OF CONTENTS MAILBACK SYSTEMS PAGES Mercury Mailback Systems .........................................5 Dental Amalgam Mailback Systems ..................................5 Biohazard Waste Mailback Systems ............................... -

US and State of Texas V. Allied Waste Industries, Inc

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS FORT WORTH DIVISION UNITED STATES OF AMERICA and Civil Action STATE OF TEXAS, No.: 497-CV 564 E Plaintiffs, v. ALLIED WASTE INDUSTRIES, INC. ' Defendant. COMPETITIVE IMPACT STATEMENT The United States, pursuant to Section 2(b) of the Antitrust Procedures and Penalties Act ("APPA"), 15 U.S.C. § 16(b)-(h), files this Competitive Impact Statement relating to the proposed Final Judgment submitted for entry in this civil antitrust proceeding. I. NATURE AND PURPOSE OF THE PROCEEDING On July 14, 1997, the United States filed a civil antitrust Complaint alleging that the proposed acquisition by Allied Waste Industries, Inc. ("Allied") of the Crow Landfill in Tarrant County, Texas from USA Waste Industries, Inc. ("USA Waste") would violate Section 7 of the Clayton Act, 15 U.S.C. § 18. An Amended Complaint was filed on July 29, 1997. The Complaint alleges that Allied and USA Waste are two of only four competitors in the greater Tarrant County area that operate commercial landfills for the disposal of municipal solid waste ("MSW") generated in Tarrant County. If 'the acquisition were consummated, there would be only three operators competing to dispose of MSW generated in Tarrant County, and that loss of competition would likely result in consumers paying higher prices for waste disposal and hauling and receiving fewer or lesser quality services. MSW disposal is a service which involves the receiving of waste at landfills from haulers which have collected paper, food, construction material and other solid wastes from homes, businesses and industries, and transported that waste to a landfill. -

Mead Johnson Announces Renewable-Energy Project

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: CarolAnn Hibbard, (508) 661-2264 [email protected] Mead Johnson Announces Renewable-Energy Project Mead Johnson Nutritionals today announced plans for an innovative project that will use landfill gas for energy at the company's manufacturing facility in Evansville. The gas will be captured at a local landfill, processed for use and transported by dedicated pipeline to Mead Johnson, where it will replace most of the company's use of natural gas. Landfill gas is a natural byproduct of the decomposition of organic materials in the landfill. Mead Johnson will work with Ameresco and Allied Waste Industries, Inc., to make this important project possible. Ameresco, which will own the system, will be responsible for designing, building, maintaining and operating it. The system will process the landfill gas into a useable fuel and then deliver it to Mead Johnson's facility via a dedicated pipeline. Allied Waste will provide the landfill gas from its Laubscher Meadows Landfill. Construction is expected to begin in June, and the process will be operational by early 2009. The project is the first of its type for Evansville and it utilizes a ""green"" technology that's been proven safe and reliable. ""Bristol-Myers Squibb and Mead Johnson are committed to environmental stewardship and sustainability around the world,"" said Mead Johnson President Steve Golsby. ""The natural gas usage eliminated through this project represents a shift from the use of fossil fuels to energy that comes from a renewable source," he added. "This is another great example of how we can be stewards of the environment and partner with businesses to achieve positive results,"" said Evansville Mayor Jonathan Weinzapfel. -

Contract for Seryice for Emergency Bio-Hazard

CONTRACT FOR SERYICE CONTRACT NO: 1445-14201, FOR EMERGENCY BIO-HAZARD CLEANUP SERVICES BETWEEN COOK COUNTY DEPARTMENT OF FACILITIES MANAGEMENT AND SET ENYIRONMENTAL, INC. (Based on City of Chicago Contract No. 16399) CONTRACTNO: 1445-14201 CONTRACT FOR SERVICE TABLE OF CONTENTS AGREEMENT .................... I BACKGRou.rD .:::::::::::::.:::::::::::::: :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: . ..... ..... .... I INCORPORATION OF BACKGR.OUND INFORMATION ...................2 INCORPORATION OF EXHIBITS ........... ...........2 List of Exhibits Exhibit I Cook County Requirements and Price Proposal Exhibit 2 Evidence of Insurance Exhibit3 IdentificationofSubcontractor/Supplier/SubconsultantForm. Exhibit 4 Electronic Payment Program Exhibit 5 MBE/\IrBE Utilization plan Exhibit 6 Economic Disclosure Statement Attachment I City of Chicago Contract (ContractNo. 16399) CONTRACTNO: 1445-14201 AGREEMENT This Agreement is made and entered into by and between the County of Cook, a public body corporate of the State of Illinois, hereinafter referred to as "Count;/" and Set Environmental, Inc., ooContractor". doing business as a corporation of the State of Illinois hereinafter referred to as ry Whereas, the County, pursuant to Section 34-140 (the Reference Contract Ordinance") of the Cook County Procurement Code, states: 'olf a govemmental agency has awarded a contract through a competitive method for the same or similar supplies, equipment, goods or services as that sought by the County, the Procurement may be made from that -

Household Hazardous Waste- an Overview of Important Topics We Protect What Matters

Solid Waste Workshop Household Hazardous Waste- An Overview of Important Topics We protect what matters. November 21, 2019 Copyright © 2018 Stericycle. All rights reserved. Introduction Overview Why are Household Hazardous Waste Collection Programs Important? Program OperationsI An Overview of How the Regulations Apply to HHW Public Awareness Local Options for Program Manager Education, Training Through Networking 2 Copyright © 2018 Stericycle. All rights reserved. Why HHW Programs Are Important WHY? Prevent environmental contamination caused by improper disposal Prevent property damage caused by improper disposal Prevent injuries to people 3 Copyright © 2018 Stericycle. All rights reserved. What is Hazardous Waste? “Waste that is dangerous or potentially harmful to our health or the environment.” - EPA IGNITABLE REACTIVE CORROSIVE TOXIC 4 Copyright © 2018 Stericycle. All rights reserved. Why HHW Programs Are Important Prevent Illegal Dumping 5 Copyright © 2018 Stericycle. All rights reserved. Why HHW Programs Are Important Prevent Property Damage 6 Copyright © 2018 Stericycle. All rights reserved. Why HHW Programs Are Important City of Buffalo, NY HHW Fire Incident 7 Copyright © 2018 Stericycle. All rights reserved. Why HHW Programs Are Important City of Kilgore, Texas HHW Trash Truck Fire BRIDGETON, Missouri 8 Copyright © 2018 Stericycle. All rights reserved. Why HHW Programs Are Important HHW is a material that could put human health or the environment at risk. Household hazardous materials constitute the most direct and frequent way the public is exposed to hazardous waste. 9 Copyright © 2018 Stericycle. All rights reserved. Why HHW Programs Are Important Facts Poison Exposures in the United States: One poison exposure every 14 seconds. 2.159 million poisonings reported in 2016 Majority of poisonings involve everyday household items such as cleaning supplies, medicines, cosmetics and personal care items. -

Engagement Report Inland Port Proposed Zoning Modifications Qualtrics Survey Results

Engagement Report Inland Port Proposed Zoning Modifications Qualtrics Survey Results Considering Typical uses of an inland port: · Rail lines that transfer freight to another mode of transportation, such as trucks · Large cranes that move freight between different transportation modes and temporary storage · Warehouses and distribution centers · Manufacturing facilities · Temporary storage of goods and materials awaiting distribution Do you see potential impacts to: Air Quality Yes No 0 50 100 150 200 250 300 350 400 # Field Choice Count 1 Yes 96.06% 390 2 No 3.94% 16 406 1 Do you see potential impacts to: Water, Sewer, or other Public Utilities Yes No 0 50 100 150 200 250 300 350 # Field Choice Count 1 Yes 89.37% 353 2 No 10.63% 42 395 2 Sensitive Natural Environments Yes No 0 50 100 150 200 250 300 350 # Field Choice Count 1 Yes 89.00% 356 2 No 11.00% 44 400 3 Salt Lake City Neighborhoods Yes No 0 50 100 150 200 250 300 # Field Choice Count 1 Yes 77.63% 302 2 No 22.37% 87 389 4 Do you have any other potential impacts you are concerned about? Not enough transparency the state doing whatever it wants w/o regard to the city or its residents Who benefits from the proposed “economic development”? Growth is to large for our area. We want a good area to enjoy. Increased population in valley, increased GHG emissions how it was created, who is on the boards, the facts that meetings are nt open My community has been footing the bill for all these public utility upgrades they say are required anyway but likely would not be. -

Medical Waste Management Plan

Revision History Medical Waste Management Plan Version: 3.1 Approved by: Philip Barruel Next Review: Biosafety Officer: Approval Date: 5/24/18 05/2019 Philip Barruel Author: Approval Date: 5/24/18 James Baugh, Ph.D., RBP Version Date Approved Author Revision Notes: 1.0 11/4/16 James Baugh Document created. 2.0 5/22/17 James Baugh Document revised per CDPH request. 3.0 5/3/18 James Baugh Document revised per CDPH request. 3.1 5/24/18 James Baugh Document revised. TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................................................ 1 A. Purpose .......................................................................................................................................................................................... 1 B. Applicability ................................................................................................................................................................................ 1 C. Roles and Responsibilities ...................................................................................................................................................... 1 D. Reference ...................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 II. Waste Identification ......................................................................................................................................................................... -

January 12, 2017 City Hall 130 Cremona Drive, Suite B Goleta

SOLID WASTE ISSUES STANDING COMMITTEE MEETING January 12, 2017 City Hall CONFERENCE ROOM 1 130 Cremona Drive, Suite B Goleta, California 2:00 P.M. Councilmember Aceves Mayor Pro Tempore Kasdin Michelle Greene, City Manager Tim Giles, City Attorney Rosemarie Gaglione, Public Works Director Everett King, Environmental Services Coordinator I. Potential Franchise Agreement Amendments needed to accommodate the recently executed Resource Recovery Project Materials Delivery Commitment & Processing Services Agreement between County of Santa Barbara and City of Goleta II. Update on State Water Resources Control Board’s Trash Amendment Americans with Disabilities Act: In compliance with the ADA, if special assistance is needed to participate in a City Council meeting (including assisted listening devices), please contact the City Clerk's office at (805) 961-7505. Notification helps to ensure that reasonable arrangements can be made to provide accessibility to the meeting. MEMORANDUM DATE: January 10, 2016 TO: Councilman Aceves Mayor Pro Tempore Kasdin FROM: Everett King, Environmental Services Coordinator SUBJECT: Potential Amendments to the Franchise Agreement for Solid Waste Handling Services between City of Goleta and MarBorg Industries _____________________________________________________________________ The recently approved Resource Recovery Project Material Delivery Commitment and Processing Services Agreement between the County of Santa Barbara and the City of Goleta (MDA) commits the City to the Tajiguas Resource Recovery Project (Project). The MDA commits the City’s solid waste stream to the Project for a 20 year term at a tipping fee that is substantially higher than those currently charged by the County for disposing refuse at the Tajiguas Landfill, and for handling and processing of residential source separated commingled recyclables (recyclables). -

Landscape Waste Compost Facilities Appendices H, I & J

Landscape Waste Compost Facilities Appendices H, I & J Appendix H Landscape Waste Compost Facility Owners and Operators Alphabetic by Facility Compost Facility Name Municipality Owner Operator Status Page 1 BFI Modern Landfill Belleville BFI Wst. Stms. of N. America Inc. Pioneer Southern Inc. A R6.19 1 Brickyard Disposal & Recycling Danville Brickyard Disposal & Recycling Inc. City of Danville A R4.23 CDT Landfill Corp. Joliet CDT Landfill Corp. CDT Landfill Corp. A R2.84 Centralia Landscape & Waste Recyc. Centralia City of Centralia, Public Works City of Centralia, Public Works A R6.20 Chicago Botanic Garden Glencoe Cook County Forest Preserve Dist. Chicago Botanic Garden A R2.85 2 2 CID RDF #4 Compost Facility Chicago Waste Management of Illinois Inc. Waste Management of Illinois Inc. A R2.86 Coles County Landfill Charleston Allied Waste Industries Inc. Allied Waste Industries Inc. A R4.24 Crystal Lake Composting Crystal Lake City of Crystal Lake, Engineering Dept. City of Crystal Lake, Engineering Dept. A R2.87 D & L Landfill Greenville D & L Landfill Inc. D & L Landfill Inc. IA R6.21 2 2 DeKalb County Landfill DeKalb Waste Management of Illinois Inc. Waste Management of Illinois Inc. A R1.22 Dirksen Parkway Compost Facility Springfield Secretary of State, Physical Services Secretary of State, Physical Services A R5.14 1 Dixon/GROP Landfill #2 Dixon City of Dixon Allied Waste Industries of Illinois A R1.23 DK-Lake Bluff Lake Bluff Village of Lake Bluff DK Recycling Systems Inc. A R2.88 Elgin Compost Facility Elgin City of Elgin City of Elgin A R2.89 1 1 Environtech Morris Environtech Inc. -

4.17 Utilities and Service Systems

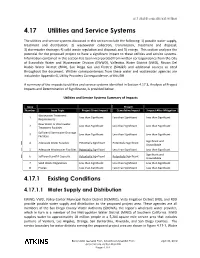

4.17 UTILITIES AND SERVICE SYSTEMS 4.17 Utilities and Service Systems The utilities and service systems discussed in this section include the following: 1) potable water supply, treatment and distribution; 2) wastewater collection, transmission, treatment and disposal; 3) stormwater drainage; 4) solid waste regulation and disposal; and 5) energy. This section analyzes the potential for the proposed project to have a significant impact to these utilities and service systems. Information contained in this section has been incorporated from written correspondence from the City of Escondido Water and Wastewater Division (EWWD), Vallecitos Water District (VWD), Rincon Del Diablo Water District (RDD), San Diego Gas and Electric (SDG&E) and additional sources as cited throughout the document. Written correspondences from these water and wastewater agencies are included in Appendix G, Utility Providers Correspondence, of this EIR. A summary of the impacts to utilities and service systems identified in Section 4.17.3, Analysis of Project Impacts and Determination of Significance, is provided below. Utilities and Service Systems Summary of Impacts Issue Project Number Issue Topic Project Direct Impact Cumulative Impact Impact After Mitigation Wastewater Treatment 1 Less than Significant Less than Significant Less than Significant Requirements New Water or Wastewater 2 Less than Significant Less than Significant Less than Significant Treatment Facilities Sufficient Stormwater Drainage 3 Less than Significant Less than Significant Less than Significant -

Recycling and Source Reduction Advisory Commission

CrIY OF MILPITAS November 5, 2009 Janis Moore' Department of Planning, Building & Code Enforcement 200 East Santa Clara Street San Jose, CA 95113 RE: DEIR for the Newby Island Rezoning Pro,ject - PDC07-07l Dear Ms. Moore: The project as defined in the draft environmental impact report (DEIR) is for a Planned Development rezoning with the purpose to allow the maximum height of the active portion of the landfill to be raised to 245 feet, adding approximately 15,12 million cubic yards to the capacity of the landflll. The new zoning would also allow changes to the uses and operations at tlle landfill and Recyclery, These changes include allowing the composting areas to be located,'" anywhere on the landfill site, allowing the processing offood waste at the Recycleo/, imposing a limit on the total number of inbound material-carrying vehicles to 1,546 vehicles per day for both the landfill and the Recycle!)', and allowing a future solid waste transfer station at fue Recyclery, The current permits that regulate the operations of the landfill and Recycle!)' restrict the areas for composting, prohibit processing offood waste at the Recyclery,and limit transfer station activities to recyclable materials, Pursuant to the California Environmental Quality Act Guidelines, an EIR should be prepared with a sufficient degree of analysis to provide decision makers with infonnation that enables them to make a decision, which intelligently takes account of environmental consequences. The Newby Island Rezoning Project DEIR failed to sufficiently analyze the significant odor impacts the project would have on the Milpitas community, The odor impacts discussed in the DEIR are identified as less than significant with no mitigation required, Yet the project's Odor Assessment (Appendix C of the DEIR) concluded that ilie project would increase the possibility of odors being transported off site and that mitigation measures are needed. -

October 2020

Klickitat County Solid Waste Management Plan - DRAFT October 2020 Klickitat County Solid Waste Management Plan October 2020 Prepared for: Klickitat County Solid Waste Department Goldendale, Washington Prepared by: Project 10172512 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Klickitat County Solid Waste Department would like to thank the following organizations and individuals for their assistance in the development of this Solid Waste Management Plan: Klickitat County Solid Waste Advisory Committee Members Name Affiliation/Title Laura Mann City of Bingen Mike Cannon City of Goldendale Donna Rockwell Citizen Representative Commissioner District #2 Steven Randall School Representative John Longfellow Citizen Representative Commissioner District #3 Jason Hartmann City of White Salmon Council Member Joe Johnson Landfill Compliance Officer James Beeks Citizen Representative At-Large / Agricultural Representative David Kavanagh Klickitat County Public Health Department Pierce Louis Agricultural Industry Representative / Business Representative Greg Bringle Waste Industry Representative Kevin Barry Citizen Representative-At-Large Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................ ES-1 1 Background ...................................................................................................................................... 1-1 1.1 Purpose .................................................................................................................................