The Unknown Bobby Fischer, Plus Original Material I’Ve Gathered for This Volume

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1999/6 Layout

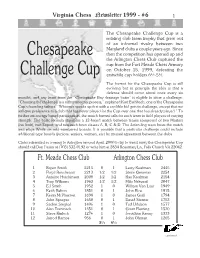

Virginia Chess Newsletter 1999 - #6 1 The Chesapeake Challenge Cup is a rotating club team trophy that grew out of an informal rivalry between two Maryland clubs a couple years ago. Since Chesapeake then the competition has opened up and the Arlington Chess Club captured the cup from the Fort Meade Chess Armory on October 15, 1999, defeating the 1 1 Challenge Cup erstwhile cup holders 6 ⁄2-5 ⁄2. The format for the Chesapeake Cup is still evolving but in principle the idea is that a defense should occur about once every six months, and any team from the “Chesapeake Bay drainage basin” is eligible to issue a challenge. “Choosing the challenger is a rather informal process,” explained Kurt Eschbach, one of the Chesapeake Cup's founding fathers. “Whoever speaks up first with a credible bid gets to challenge, except that we will give preference to a club that has never played for the Cup over one that has already played.” To further encourage broad participation, the match format calls for each team to field players of varying strength. The basic formula stipulates a 12-board match between teams composed of two Masters (no limit), two Expert, and two each from classes A, B, C & D. The defending team hosts the match and plays White on odd-numbered boards. It is possible that a particular challenge could include additional type boards (juniors, seniors, women, etc) by mutual agreement between the clubs. Clubs interested in coming to Arlington around April, 2000 to try to wrest away the Chesapeake Cup should call Dan Fuson at (703) 532-0192 or write him at 2834 Rosemary Ln, Falls Church VA 22042. -

Kolov LEADS INTERZONAL SOVIET PLAYERS an INVESTMENT in CHESS Po~;T;On No

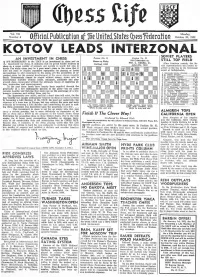

Vol. Vll Monday; N umber 4 Offjeitll Publication of me Unttecl States (bessTederation October 20, 1952 KOlOV LEADS INTERZONAL SOVIET PLAYERS AN INVESTMENT IN CHESS Po~;t;on No. 91 POI;l;"n No. 92 IFE MEMBERSHIP in the USCF is an investment in chess and an Euwe vs. Flohr STILL TOP FIELD L investment for chess. It indicates that its proud holder believes in C.1rIbad, 1932 After fOUl't~n rounds, the S0- chess ns a cause worthy of support, not merely in words but also in viet rcpresentatives still erowd to deeds. For while chess may be a poor man's game in the sense that it gether at the top in the Intel'l'onal does not need or require expensive equipment fm' playing or lavish event at Saltsjobaden. surroundings to add enjoyment to the game, yet the promotion of or· 1. Alexander Kot()v (Russia) .w._.w .... 12-1 ganized chess for the general development of the g'lmc ~ Iway s requires ~: ~ ~~~~(~tu(~~:I;,.i ar ·::::~ ::::::::::~ ~!~t funds. Tournaments cannot be staged without money, teams sent to international matches without funds, collegiate, scholastic and play· ;: t.~h!"'s~~;o il(\~::~~ ry i.. ··::::::::::::ij ); ~.~ ground chess encouraged without the adequate meuns of liupplying ad· 6. Gidcon S tahl ~rc: (Sweden) ...... 81-5l vice, instruction and encouragement. ~: ~,:ct.~.:~bG~~gO~~(t3Ji;Oi· · ·:::: ::::::7i~~ In the past these funds have largely been supplied through the J~: ~~j~hk Elrs'l;~san(A~~;t~~~ ) ::::6i1~ generosity of a few enthusiastic patrons of the game-but no game 11. -

The Wangling Wizards the Chess Problems of the Warton Brothers

The Wangling Wizards The chess problems of the Warton brothers Compiled by Michael McDowell ½ û White to play and mate in 3 British Chess Problem Society 2005 The Wangling Wizards Introduction Tom and Joe Warton were two of the most popular British chess problem composers of the twentieth century. They were often compared to the American "Puzzle King" Sam Loyd because they rarely composed problems illustrating formal themes, instead directing their energies towards hoodwinking the solver. Piquant keys and well-concealed manoeuvres formed the basis of a style that became known as "Wartonesque" and earned the brothers the nickname "the Wangling Wizards". Thomas Joseph Warton was born on 18 th July 1885 at South Mimms, Hertfordshire, and Joseph John Warton on 22 nd September 1900 at Notting Hill, London. Another brother, Edwin, also composed problems, and there may have been a fourth composing Warton, as a two-mover appeared in the August 1916 issue of the Chess Amateur under the name G. F. Warton. After a brief flourish Edwin abandoned composition, although as late as 1946 he published a problem in Chess . Tom and Joe began composing around 1913. After Tom’s early retirement from the Metropolitan Police Force they churned out problems by the hundred, both individually and as a duo, their total output having been estimated at over 2600 problems. Tom died on 23rd May 1955. Joe continued to compose, and in the 1960s published a number of joints with Jim Cresswell, problem editor of the Busmen's Chess Review , who shared his liking for mutates. Many pleasing works appeared in the BCR under their amusing pseudonym "Wartocress". -

The Modern Defence: Move by Move PDF Book

THE MODERN DEFENCE: MOVE BY MOVE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Cyrus Lakdawala | 400 pages | 20 Nov 2012 | EVERYMAN CHESS | 9781857449860 | English | London, United Kingdom The Modern Defence: Move by Move PDF Book Please try to maintain a semblance of civility at all times. When to resign - Etiquette - An honest appeal Optimissed 7 min ago. Published November 20th by Everyman Chess first published October 7th Cochrane vs Somacarana 34 Calcutta B06 Robatsch 8. Rxh7 9. Error rating book. Nc3 in the actual game. Aug 10, Chapter 1 — Introduction — initial remarks and comments. Cyrus Lakdawala. I know he is notoriously hit-and-miss as an author. Kxf7, 6. The flexibility and toughness of the Modern Defense has provoked some very aggressive responses by White, including the crudely named Monkey's Bum , a typical sequence being 1. Welcome back. Chapter 8 — The Fianchetto Variation: g3-Bg2 setups — the quiet, but no less venomous setups involving an early fianchetto of the light-squared bishop. Question feed. Bg7 3. See something that violates our rules? Please observe our posting guidelines: No obscene, racist, sexist, or profane language. Be2, Black can retreat the knight or gambit a pawn with Therefore, I find it an advantage to block these pieces by pawns. Nf3, Black can play Jul 22, 2. Numerous hours were spent analyzing, importing, commenting, fixing mistakes, fixing the fixes of mistakes, replying to beta tester comments, improving the initial version, etc. B06 Robatsch. Transpositions are possible after 2. A repertoire for my favourite opening for the Black pieces — the Modern Defence — was among them. To ask other readers questions about The Modern Defence , please sign up. -

“CHECKMATE” FIRST EDITION Issue 1

“CHECKMATE” FIRST EDITION Issue 1 “CHECKMATE” FIRST EDITION 2013, Botswana Chess Review In this Issue; BY: KEENESE NEOYAME KATISENGE 1. Historic World Chess Federation’s Visit to Botswana 2. Field Performance 3. Administration & Developmental Programs BCF PUBLIC RELATIONS DIRECTOR 4. Social Responsibility, Marketing and Publicity / Sponsorships B “Checkmate” is the first edition of BCF e-Newsletter. It will be released on a quarterly basis with a review of chess events for the past period. In Chess circles, “Checkmate” announces the end of the game the same way this newsletter reviews performance at the end of a specified period. The aim of “Checkmate” is to maintain contact with all stakeholders, share information with interesting chess highlights as well as increase awareness in a BNSC Chair Solly Reikeletseng,Mr Mogotsi from Debswana, cost-effective manner. Mr Bobby Gaseitsewe from BNSC and BCF Exo during The 2013 Re-ba bona-ha Youth Championships 2013, Botswana Chess Review Under the leadership of the new president, Tshenolo Maruatona,, Botswana Chess continues to steadily Minister of Youth, Sports & Culture Hon. Shaw Kgathi and cement its place as one of the fastest growing the FIDE Delegation during their visit to Botswana in 2013 sporting codes in the country. BCF has held a number of activities aimed at developing and growing the sport in the country. “CHECKMATE” FIRST EDITION | Issue 1 2 2013 Review Cont.. The president of the federation, Mr Maruatona attended two key International Congresses, i.e Zonal Meeting held during The -

2001 07 En Passant

5604 Solway Street Suite 209 July 2001 Pittsburgh PA 15217-1270 Vol 57 No 4 412-421-1881 “I swear, Bob, part of me wants to go to the World Series with you, but another part wants to analyze game 19 of the Spassky-Fischer match.” to PCC members. Re-entry: $15. 3-day schedule: Reg ends En Passant Fri 6:30pm, Rds Fri 7, Sat 12:30 - 5:30, Sun 10 - 3. 2-day Journal of the Pittsburgh Chess Club schedule: Reg Sat 9:30-9:45am, 1st Round 10am, then merges with 3-day. Bye: 1-5, rds 4 & 5 must commit before rd Chess Journalists of America Award 2. HR: $31-41, Univ. of Pittsburgh Main Towers dorms 412- Best Club Bulletin, 2000 648-1206. Info: 412-681-7590. Ent: Tom Martinak. http://trfn.clpgh.org/orgs/pcc/ July 17. PCC Executive Committee Meeting. Pittsburgh Club Telephone: 412-421-1881 Chess Club. 6pm. Hours: Wednesday 1 - 10 PM; Saturday Noon - 10:30 PM July 17 - August 14. 10th Wild Card Open. 5-SS. Pitts- burgh Chess Club. 2 sections: Championship. TL: 30/90, Editor: Bobby Dudley, 107 Crosstree Road SD/60. EF: $28 postmarked by 7/9, $38 at site, $2 discount to Moon Township PA 15108-2607 PCC members. $$ (540 b/27): 140-100-90-80-70-60. 412-262-2138 or 412-262-4079 Booster, open to U1600. TL: Game/60. EF: $14 postmarked [email protected] by 7/9, $19 at site, $1 discount to PCC members. Trophies to Interim Editor: Thomas Martinak, 320 N Neville St Apt 22 1st & 2nd, Ribbons to 3rd. -

Of Kings and Pawns

OF KINGS AND PAWNS CHESS STRATEGY IN THE ENDGAME ERIC SCHILLER Universal Publishers Boca Raton • 2006 Of Kings and Pawns: Chess Strategy in the Endgame Copyright © 2006 Eric Schiller All rights reserved. Universal Publishers Boca Raton , Florida USA • 2006 ISBN: 1-58112-909-2 (paperback) ISBN: 1-58112-910-6 (ebook) Universal-Publishers.com Preface Endgames with just kings and pawns look simple but they are actually among the most complicated endgames to learn. This book contains 26 endgame positions in a unique format that gives you not only the starting position, but also a critical position you should use as a target. Your workout consists of looking at the starting position and seeing if you can figure out how you can reach the indicated target position. Although this hint makes solving the problems easier, there is still plenty of work for you to do. The positions have been chosen for their instructional value, and often combined many different themes. You’ll find examples of the horse race, the opposition, zugzwang, stalemate and the importance of escorting the pawn with the king marching in front, among others. When you start out in chess, king and pawn endings are not very important because usually there is a great material imbalance at the end of the game so one side is winning easily. However, as you advance through chess you’ll find that these endgame positions play a great role in determining the outcome of the game. It is critically important that you understand when a single pawn advantage or positional advantage will lead to a win and when it will merely wind up drawn with best play. -

I Make This Pledge to You Alone, the Castle Walls Protect Our Back That I Shall Serve Your Royal Throne

AMERA M. ANDERSEN Battlefield of Life “I make this pledge to you alone, The castle walls protect our back that I shall serve your royal throne. and Bishops plan for their attack; My silver sword, I gladly wield. a master plan that is concealed. Squares eight times eight the battlefield. Squares eight times eight the battlefield. With knights upon their mighty steed For chess is but a game of life the front line pawns have vowed to bleed and I your Queen, a loving wife and neither Queen shall ever yield. shall guard my liege and raise my shield Squares eight times eight the battlefield. Squares eight time eight the battlefield.” Apathy Checkmate I set my moves up strategically, enemy kings are taken easily Knights move four spaces, in place of bishops east of me Communicate with pawns on a telepathic frequency Smash knights with mics in militant mental fights, it seems to be An everlasting battle on the 64-block geometric metal battlefield The sword of my rook, will shatter your feeble battle shield I witness a bishop that’ll wield his mystic sword And slaughter every player who inhabits my chessboard Knight to Queen’s three, I slice through MCs Seize the rook’s towers and the bishop’s ministries VISWANATHAN ANAND “Confidence is very important—even pretending to be confident. If you make a mistake but do not let your opponent see what you are thinking, then he may overlook the mistake.” Public Enemy Rebel Without A Pause No matter what the name we’re all the same Pieces in one big chess game GERALD ABRAHAMS “One way of looking at chess development is to regard it as a fight for freedom. -

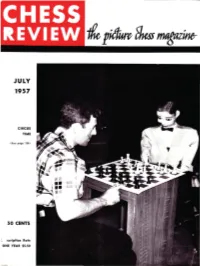

CHESS REVIEW but We Can Give a Bit More in a Few 250 West 57Th St Reet , New York 19, N

JULY 1957 CIRCUS TIME (See page 196 ) 50 CENTS ~ scription Rate ONE YEAR $5.50 From the "Amenities and Background of Chess-Play" by Ewart Napier ECHOES FROM THE PAST From Leipsic Con9ress, 1894 An Exhibition Game Almos t formidable opponent was P aul Lipk e in his pr ime, original a nd pi ercing This instruc tive game displays these a nd effective , Quite typica l of 'h is temper classical rivals in holiUay mood, ex is the ",lid Knigh t foray a t 8. Of COU I'se, ploring a dangerous Queen sacrifice. the meek thil'd move of Black des e r\" e~ Played at Augsburg, Germany, i n 1900, m uss ing up ; Pillsbury adopted t he at thirty moves an hOlll" . Tch igorin move, 3 . N- B3. F A L K BEE R COU NT E R GAM BIT Q U EE N' S PAW N GA ME" 0 1'. E. Lasker H. N . Pi llsbury p . Li pke E. Sch iffers ,Vhite Black W hite Black 1 P_K4 P-K4 9 8-'12 B_ KB4 P_Q4 6 P_ KB4 2 P_KB4 P-Q4 10 0-0- 0 B,N 1 P-Q4 8-K2 Mate announred in eight. 2 P- K3 KN_ B3 7 N_ R3 3 P xQP P-K5 11 Q- N4 P_ K B4 0 - 0 8 N_N 5 K N_B3 12 Q-N3 N-Q2 3 B-Q3 P- K 3? P-K R3 4 Q N- B3 p,p 5 Q_ K2 B-Q3 13 8-83 N-B3 4 N-Q2 P-B4 9 P-K R4 6 P_Q3 0-0 14 N-R3 N_ N5 From Leipsic Con9ress. -

Chess Review

MARCH 1968 • MEDIEVAL MANIKINS • 65 CENTS vI . Subscription Rat. •• ONE YEAR $7.S0 • . II ~ ~ • , .. •, ~ .. -- e 789 PAGES: 7'/'1 by 9 inches. clothbound 221 diagrams 493 ideo variations 1704 practical variations 463 supplementary variations 3894 notes to all variations and 439 COMPLETE GAMES! BY I. A . HOROWITZ in collaboration with Former World Champion, Dr, Max Euwe, Ernest Gruenfeld, Hans Kmoch, and many other noted authorities This Jatest and immense work, the mo~t exhaustive of i!~ kind, e:x · plains in encyclopedic detail the fine points of all openings. It carries the reader well into the middle game, evaluates the prospects there and often gives complete exemplary games so that he is not teft hanging in mid.position with the query : What bappens now? A logical sequence binds the continuity in each opening. Firsl come the moves with footnotes leading to the key position. Then fol· BIBLIOPHILES! low perlinenl observations, illustrated by "Idea Variations." Finally, Glossy paper, handsome print. Practical and Supplementary Variations, well annotated, exemplify the effective possibilities. Each line is appraised : or spacious poging and a ll the +, - = . The large format-71/2 x 9 inches- is designed for ease of rcad· other appurtenances of exquis· ing and playing. It eliminates much tiresome shuffling of pages ite book-making combine to between the principal lines and the respective comments. Clear, make this the handsomest of legible type, a wide margin for inserting notes and variation·identify· ing diagrams are other plus features. chess books! In addition to all else, fhi s book contains 439 complete ga mes- a golden trea.mry in itself! ORDER FROM CHESS REVIEW 1- --------- - - ------- --- - -- - --- -I I Please send me Chess Openings: Theory and Practice at $12.50 I I Narne • • • • • • • • • • . -

A Glimpse Into the Complex Mind of Bobby Fischer July 24, 2014 – June 7, 2015

Media Contact: Amanda Cook [email protected] 314-598-0544 A Memorable Life: A Glimpse into the Complex Mind of Bobby Fischer July 24, 2014 – June 7, 2015 July XX, 2014 (Saint Louis, MO) – From his earliest years as a child prodigy to becoming the only player ever to achieve a perfect score in the U.S. Chess Championships, from winning the World Championship in 1972 against Boris Spassky to living out a controversial retirement, Bobby Fischer stands as one of chess’s most complicated and compelling figures. A Memorable Life: A Glimpse into the Complex Mind of Bobby Fischer opens July 24, 2014, at the World Chess Hall of Fame (WCHOF) and will celebrate Fischer’s incredible career while examining his singular intellect. The show runs through June 7, 2015. “We are thrilled to showcase many never-before-seen artifacts that capture Fischer’s career in a unique way. Those who study chess will have the rare opportunity to learn from his notes and books while casual fans will enjoy exploring this superstar’s personal story,” said WCHOF Chief Curator Bobby Fischer, seen from above, Shannon Bailey. makes a move during the 1966 Piatigorsky Cup. Several of the rarest pieces on display are on generous loan from Dr. Jeanne and Rex Sinquefield, owners of a a collection of material from Fischer’s own library that includes 320 books and 400 periodicals. These items supplement highlights from WCHOF’s permanent collection to create a spectacular show. Highlights from the exhibition: Furniture from the home of Fischer’s mentor Jack Collins, which -

Chess-Training-Guide.Pdf

Q Chess Training Guide K for Teachers and Parents Created by Grandmaster Susan Polgar U.S. Chess Hall of Fame Inductee President and Founder of the Susan Polgar Foundation Director of SPICE (Susan Polgar Institute for Chess Excellence) at Webster University FIDE Senior Chess Trainer 2006 Women’s World Chess Cup Champion Winner of 4 Women’s World Chess Championships The only World Champion in history to win the Triple-Crown (Blitz, Rapid and Classical) 12 Olympic Medals (5 Gold, 4 Silver, 3 Bronze) 3-time US Open Blitz Champion #1 ranked woman player in the United States Ranked #1 in the world at age 15 and in the top 3 for about 25 consecutive years 1st woman in history to qualify for the Men’s World Championship 1st woman in history to earn the Grandmaster title 1st woman in history to coach a Men's Division I team to 7 consecutive Final Four Championships 1st woman in history to coach the #1 ranked Men's Division I team in the nation pnlrqk KQRLNP Get Smart! Play Chess! www.ChessDailyNews.com www.twitter.com/SusanPolgar www.facebook.com/SusanPolgarChess www.instagram.com/SusanPolgarChess www.SusanPolgar.com www.SusanPolgarFoundation.org SPF Chess Training Program for Teachers © Page 1 7/2/2019 Lesson 1 Lesson goals: Excite kids about the fun game of chess Relate the cool history of chess Incorporate chess with education: Learning about India and Persia Incorporate chess with education: Learning about the chess board and its coordinates Who invented chess and why? Talk about India / Persia – connects to Geography Tell the story of “seed”.