An Early Map on Skin of the Area Later to Become Indiana and Illinois

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WABASH VALLEY COMMUNITY FOUNDATION 2016 ANNUAL REPORT 2 Letter from the President 21 Ways to Make a Difference 4 Lilly Endowment Inc

WABASH VALLEY COMMUNITY FOUNDATION 2016 ANNUAL REPORT 2 Letter from the President 21 Ways to Make a Difference 4 Lilly Endowment Inc. 22 Funds GIFT VI Challenge 26 Donors Make a Difference 6 Making a Difference in 32 Legacy Society the Wabash Valley 34 Memorials and Honorariums 12 Grants 36 Financials 18 Scholarships 38 Boards 20 Make a Difference through the 40 Staff, Interns, and Committees Community Foundation THE DIFFERENCE IS YOU. At the Wabash Valley Community Foundation, we realize The Difference is You. When you donate to the Community Foundation, you are one of many individuals choosing to make a difference by building a strong future for our communities. When you partner with us to fulfill your charitable goals, you help nonprofit organizations transform our communities, making Clay, Sullivan and Vigo counties better places to live, work and play. Whatever your reason for choosing to make a difference, we are proud to assist MISSION you and help you realize your philanthropic dreams within our communities. The mission of the Wabash Valley For good. For ever.® Community Foundation is to engage people, build resources and strengthen community in the Wabash Valley. VISION The Wabash Valley Community Foundation will be the primary steward of endowed funds and a leader that encourages broad-based charitable activity in the Wabash Valley. You HAVE MADE THE DIFFERENCE. Thank YOU! 2016 WAS an extraordinary year for the Wabash 23 years of renting, we decided to invest in our carried out their stewardship roles by conducting Valley Community Foundation. I have completed own property, adapting a mid-century modern an arduous Request for Proposals process for both my fourth and final year as president of THE building to provide office space for us and a marketing firm and an investment consultant. -

Reflection Seismic Profiling of the Wabash Valley Fault System in the Illinois Basin

Reflection Seismic Profiling of the Wabash Valley Fault System in the Illinois Basin U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 1538-0 MISSOURI ~"3t3fc: «tr- ^t-i. ARKANSAS Cover. Gray, shaded-relief map of magnetic anomaly data. Map area includes parts of Missouri, Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Tennessee, and Arkansas. Illumination is from the west. Figure is from Geophysical setting of the Reelfoot rift and relations between rift structures and the New Madrid seismic zone, by Thomas G. Hildenbrand and John D. Hendricks (chapter E in this series). Reflection Seismic Profiling of the Wabash Valley Fault System in the Illinois Basin By R.M. Rene and F.L. Stanonis INVESTIGATIONS OF THE NEW MADRID SEISMIC ZONE Edited by Kaye M. Shedlock and Arch C. Johnston U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 1538-O This research was jointly supported by the U.S. Geological Survey and ARPEX (Industrial Associates' Research Program in Exploration Seismology—Indiana University, University of Southern Indiana, Indiana Geological Survey) UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1995 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BRUCE BABBITT, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Gordon P. Eaton, Director For sale by U.S. Geological Survey, Information Services Box 25286, Federal Center Denver, CO 80225 Any use of trade, product, or firm names in this publication is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rene, R.M. Reflection seismic profiling of the Wabash Valley fault system in the Illinois Basin / by R.M. Rend and F.L. Stanonis. p. cm.—(U.S. -

Wabash County, Illinois Multi-Hazard Mitigation Plan 2017 Countywide MHMP Wabash County Multi-Hazard Mitigation Plan

Wabash County, Illinois Multi-Hazard Mitigation Plan 2017 Countywide MHMP Wabash County Multi-Hazard Mitigation Plan Multi-Hazard Mitigation Plan Wabash County, Illinois Adoption Date: -- _______________________ -- Primary Point of Contact Secondary Point of Contact Gerald Brooks Sarah Mann Coordinator Executive Director Wabash County Emergency Management Agency Greater Wabash Regional Planning Commission 930 ½ Market Street 10 West Main Street Mount Carmel, Illinois 62863 Albion, Illinois 62806 Phone: (618) 262-6715 Phone: (618) 445-3612 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] i Wabash County Multi-Hazard Mitigation Plan Acknowledgements The Wabash County Multi-Hazard Mitigation Plan would not have been possible without the feedback, input, and expertise provided by the County leadership, citizens, staff, federal and state agencies, and volunteers. We would like to give special thank you to the citizens not mentioned below who freely gave their time and input in hopes of building a stronger, more progressive County. Wabash County gratefully acknowledges the following people for the time, energy and resources given to create the Wabash County Multi-Hazard Mitigation Plan. Wabash County Board Robert Dean County Board Chairman Robie Thompson Tim Hocking ii Wabash County Multi-Hazard Mitigation Plan Table of Contents Section 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 1 Section 2. Planning Process ................................................................................................................... -

Guide to the Geology of the Mount Carmel Area, Wabash County, Illinois

557 IL6gui 1996-D Guide to the Geology of the Mount Carmel Area, Wabash County, Illinois W.T. Frankie, R.J. Jacobson, and B.G. Huff Illinois State Geological Survey M.B. Thompson Amax Coal Company K.S. Cummings and C.A. Phillips Illinois Natural History Survey Field Trip Guidebook 1996D October 26, 1996 Department of Natural Resources ILLINOIS STATE GEOLOGICAL SURVEY ON THE BANKS OF THE WABASH, FAR AWAY VERSE 1 Round my Indiana homestead wave the corn fields, In the distance loom the woodlands clear and cool. Often times my thoughts revert to scenes of childhood, Where I first received my lessons, nature's school. But one thing there is missing in the picture, Without her face it seems so incomplete. I long to see my mother in the doorway, As she stood there years ago, her boy to greet! CHORUS Oh, the moonlight's fair tonight along the Wabash, From the fields there comes the breath of new mown hay. Through the sycamores the candle lights are gleaming, On the banks of the Wabash, far away. VERSE 2 Many years have passed since I strolled by the river, Arm in arm with sweetheart Mary by my side. It I was there tried to tell her that I loved her, It was there I begged of her to be my bride. Long years have passed since I strolled through the churchyard, She's sleeping there my angel Mary dear. I loved her but she thought I didn't mean it, Still I'd give my future were she only here. -

An Inventory of Local Governments in Illinois

AN INVENTORY OF LOCAL GOVERNMENTS IN ILLINOIS February 25, 2021 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................................................... 1 DIFFERENCES AMONG REPORTING AGENCIES ........................................................................................................... 3 MAJOR FINDINGS ....................................................................................................................................................... 7 Additional Findings ............................................................................................................................................ 10 METHODOLOGY & DATA ......................................................................................................................................... 10 OVERVIEW OF LOCAL GOVERNMENTS ........................................................................................................ 13 DESCRIPTION OF LOCAL GOVERNMENTS ................................................................................................................. 13 General Purpose Local Governments ................................................................................................................ 13 Special Purpose Local Governments ................................................................................................................. 15 POPULATIONS OF LOCAL GOVERNMENTS IN ILLINOIS ............................................................................................ -

M5.4 Mount Carmel, Illinois, Earthquake of 18 April 2008

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR EARTHQUAKE SUMMARY MAP XXX U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY M5.4 Mount Carmel, Illinois, Earthquake of 18 April 2008 Prepared in cooperation with the Global Seismographic Network Tectonic Setting 100° 95° 90° 85° 80° Predicted Shaking 45° Saint MICHIGAN MICHIGAN 45° Illinois Basin Paul Epicentral Region 90° 88° 86° Minneapolis WISCONSIN Lake WISCONSIN 18 April 2008 9:37:00 UTC SOUTH MINNESOTA Huron r e Bloomington DAKOTA WISCONSIN iv 38.45° N., 87.89° W. Toronto R L. Ontario is Depth 11.6 km Lake o n Michigan Rochester lli Mw = 5.4 (USGS) NEW YORK I Muncie Milwaukee MICHIGAN Buffalo Anderson NEW Champaign Reports of minor structural damage in West Salem, MICHIGAN 40° 40° Detroit YORK Illinois and Louisville, Kentucky. Felt over a wide PENNSYLVANIA area of the central United States with felt reports as ILLINOIS M Decatur OHIO OHIO is Springfield Indianapolis far west as Kansas, as far north as the Upper IOWA s Chicago Lake Erie is s Peninsula of Michigan and as far south as Georgia. NEBRASKA ip p Cleveland i R Terre PENNSYLVANIA iv e Haute Hamilton Pittsburgh r 40° Columbus 40° INDIANA ILLINOIS Bloomington Indianapolis OHIO Cincinnati MARYLAND ILLINOIS Kansas Wabash Valley INDIANA Cincinnati City liquefaction Saint St. Peters Louis features WEST KANSAS VIRGINIA Saint Central MISSOURI Charles Kentucky River Virginia Saint St. Louis-Cape fault system seismic zone Giradeau liquefaction Pembroke Louis (Class B) features faults VIRGINIA 1812 Mount Carmel Louisville 1812 KENTUCKY (Class B) Lexington- Western lowlands Fayette -

DYKI%A Gosse~ P ROFESSIONAL LHIED L IABILITY C OMPANY

LAW OFFICES DYKI%A GoSSE~ P ROFESSIONAL LHIED L IABILITY C OMPANY 800 M ICHIGAN NnnoNnL T OWER ANSING ICHIGAN Detroit, Michigan Ann Arbor, Michigan L , M 48933- I 742 Grand Rapids, Mlchlgan Bloomfleld Hills, Michigan Washington, DC Chicago, Illinois T ELEPHONE (5 I 7) 374-Q IO0 F ACSIMILE (5 I 7) 374-Q I Q I WWW.DYKEMA.COt-4 DIRECT DIAL: (511) 324-91&k E-MAIL:[email protected] April lo,2002 Ms. Dorothy Wideman Executive Secretary Michigan Public Service Commission 6545 Mercantile Way, Ste. 7 Lansing, MI 48911 Re: Case No. U-1261 1-R WVPA 2001 PSCR Reconciliation Midwest Petition to Intervene Dear Ms. Wideman: Enclosed please find original and four copies of Petition to Intervene of Midwest Energy Cooperative in the above-referenced matter. Also enclosed is Proof of Service upon the parties of record. Pursuant to the Notice of Hearing in this matter, the Petition is also being electronically filed If there are any questions or comments, do not hesitate to contact me. Sincerely, D-MA GOSSETT PLLC Christine Mason Soneral CMS/jmb Enclosure cc: Bob Hance Mark Stallons John Miner LANO1\92305.1 ID\CMMA STATE OF MICHIGAN BEFORE THE MICHIGAN PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION ***** In the matter of WABASH VALLEY POWER ) ASSOCIATION, INC.% Power Supply Cost ) Reconciliation Proceeding for the twelve- ) Case No. U-1261 1-R month period ending December 31,200l. ) PETITION TO INTERVENE OF MIDWEST ENERGY COOPERATIVE 8 d NOW COMES Midwest Energy Cooperative (“Midwest”), by and through its 8 i attorneys, DYKEMA GOSSETT PLLC, and petitions to intervene in the above-entitled matter. -

Wabash Valley Fault System

WABASH VALLEY FAULT SYSTEM Chapter 6 SSC Model: Mmax Zones Branch Figure 6.1.9-2 Map showing seismicity, subsurface structural features, paleoearthquake energy centers, and postulated neotectonic deformation in the Wabash Valley region of southern Illinois and southern Indiana Fig 6.1.9.2 CEUS6 -SSC161 report RECENT WABASH REFERENCES • Obermeier, S. F., 2009, Using liquefaction-induced and other soft-sediment features for paleoseismic analysis: International Geophysics, v. 95, pp. 499-566. • Van Arsdale, R., Counts, R., and Woolery, E., 2009, Quaternary Displacement Along the Hovey Lake Fault of Southern Indiana and Western Kentucky: NEHRP Final report submitted to the U.S. Geological Survey, External Grant Number 07HQGR0052, 11 pp. • Counts, R.C., Durbin, J.M., and Obermeier, S.F., 2008, Seismic ground-failure features in the vicinity of the Lower Wabash and Ohio River valleys: in Counts, M.H., and Counts, R.C. (editors), From the Cincinnati Arch to the Illinois Basin: Geological Field Excursions Along the Ohio River Valley: Geological Society of America Field Guide 12, pp. 57-79. • McBride, J.H., Leetaru, H.E., Bauer, R.A., Tingey, B.E., and Schmidt, S.E.A., 2007, Deep faulting and structural reactivation beneath the southern Illinois basin: Precambrian Research, v. 157, pp. 289–313, doi:10.1016/j.precamres.2007.02.020. • Abstracts • Counts, R., Van Arsdale, R., Tuttle, M., Mahan, S. Obermeier, S., and Woolery, E., 2011 Paleoseismology in the New Madrid and Wabash Valley Seismic Zones, central United States [abs.]: XVIII INQUA Bern 2011, link • Counts, R., Van Arsdale, R., and Woolery, E., 2009b, Paleoseismic Features Within the Wabash Valley Seismic Zone in Western Kentucky: presentation given at meeting of CEUS Earthquake Hazards Program, U.S. -

2016 Illinois Soil & Water Conservation Districts Directory

State of Illinois Department of Agriculture Raymond Poe, Director 2016 ILLINOIS SOIL & WATER CONSERVATION DISTRICTS DIRECTORY September 2016 ILLINOIS DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE Illinois State Fairgrounds P.O. Box 19281 Springfield, IL 62794-9281 217/782-2172 217/524-6858 (TDD) www.agr.state.il.us Raymond Poe Director Warren Goetsch Deputy Director Grant Hammer Chief-of-Staff Craig Sondgeroth General Counsel Division of Natural Resources Vacant Division Manager Steve Chard Vacant Acting Bureau Chief Bureau Chief Land and Water Resources Environmental Programs Printed by the Authority of the State of Illinois #16-551/9-16 /100 copies ILLINOIS DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE BUREAU OF LAND AND WATER RESOURCES 801 E. Sangamon Avenue, P.O. Box 19281, Springfield, IL 62794-9281 Phone: 217/782-6297 Fax: 217/557-0993 Steve Chard, Acting Bureau Chief, 217/785-2661 [email protected] Office Staff: Deanna Clark 217/782-6297 [email protected] Carrie Tisckos 217/524-0103 [email protected] OFFICE OF FARMLAND PROTECTION & MINED LAND RECLAMATION Office Staff: Terry Savko 217/785-4458 [email protected] John Lohse 217/785-4389 [email protected] OFFICE OF NATURAL RESOURCE MANAGEMENT Office Staff: Vacant Regional Representatives: Region One – Marty McManus Region Four – Elliot Lagacy [email protected] [email protected] 309/738-7227 217/353-6603 Region Two – Joe Bybee Region Five – Gary Albers [email protected] [email protected] 815/787-5480 618/476-7230 Region Three – Vacant TABLE OF CONTENTS SWCDs -

An Archaeological Survey of the Wabash Valley in Illinois

LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY QF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN 507 '• r CENTRAL CIRCULATION BOOKSTACKS The person charging this material is re- sponsible for its renewal or its return to the library from which it was borrowed on or before the Latest Date stamped below. You may be charged a minimum fee of $75.00 for each lost book. are reason* Thoft, imtfOaHM, and underlining of bck. dismissal from for dtelpltaary action and may result In TO RENEW CML TELEPHONE CENTER, 333-8400 UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS LIBRARY AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN APR 2003 MG 1 2 1997 AUG 2 4 2006 AUG 2 3 1999 AUG 13 1999 1ft 07 WO AU6 23 2000 9 10 .\ AUG 242000 Wh^^ie^i^ $$$ae, write new due date below previous due date. 1*162 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 http://archive.org/details/archaeologicalsu10wint Howard D. Winters s AN ARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEY OFTHE WABASH VALLEYin Illinois mmm* THE 3 1367 . \ Illinois State Museum STATE OF ILLINOIS Otto Kerner, Governor DEPARTMENT OF REGISTRATION AND EDUCATION John C. Watson, Director ILLINOIS STATE MUSEUM Milton D. Thompson, Museum Director REPORTS OF INVESTIGATIONS. No. 10 AN ARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF THE WABASH VALLEY IN ILLINOIS by Howard D. Winters Printed by Authority of the State of Illinois Springfield, Illinois 1967 BOARD OF THE ILLINOIS STATE MUSEUM Everett P. Coleman, M.D., Chairman Coleman Clinic, Canton Myers John C.Watson Albert Vice-President, Myers Bros. Director, Department of Springfield Registration and Education Sol Tax, Ph.D., Secretary William Sylvester White of Anthropology Professor Judge, Circuit Court Dean, University Extension Cook County, Chicago University of Chicago Leland Webber C. -

List of Secondary Schools (As of 11/21/08)

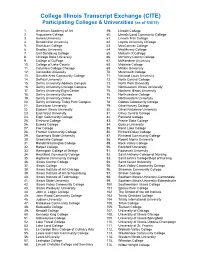

College Illinois Transcript Exchange (CITE) Participating Colleges & Universities (as of 5/8/15) 1. American Academy of Art 59. Lincoln College 2. Augustana College 60. Lincoln Land Community College 3. Aurora University 61. Lincoln Trail College 4. Benedictine University 62. Loyola University Chicago 5. Blackburn College 63. MacCormac College 6. Bradley University 64. MacMurray College 7. Carl Sandburg College 65. Malcolm X College 8. Chicago State University 66. McHenry County College 9. College of DuPage 67. McKendree University 10. College of Lake County 68. Midstate College 11. Columbia College Chicago 69. Millikin University 12. Concordia University 70. Monmouth College 13. Danville Area Community College 71. National Louis University 14. DePaul University 72. North Central College 15. DeVry University-Addison Campus 73. North Park University 16. DeVry University-Chicago Campus 74. Northeastern Illinois University 17. DeVry University-Elgin Center 75. Northern Illinois University 18. DeVry University-Gurnee 76. Northwestern College 19. DeVry University-Online 77. Northwestern University 20. DeVry University-Tinley Park Campus 78. Oakton Community College 21. Dominican University 79. Olive Harvey College 22. Eastern Illinois University 80. Olivet Nazarene University 23. East-West University 81. Olney Central College 24. Elgin Community College 82. Parkland College 25. Elmhurst College 83. Prairie State College 26. Eureka College 84. Quincy University 27. Fox College 85. Rend Lake College 28. Frontier Community College 86. Richard Daley College 29. Governors State University 87. Richland Community College 30. Greenville College 88. Robert Morris University 31. Harold Washington College 89. Rock Valley College 32. Harper College 90. Rockford University 33. Harrington College of Design 91. Roosevelt University 34. -

CAPITAL DEVELOPMENT BOARD Agenda Item 3

CAPITAL DEVELOPMENT BOARD Agenda Item SUBJECT: Meeting Minutes for August 12, 2014 Board Meeting The August 12, 2014 meeting of the Capital Development Board was held by video- conference at the James R. Thompson Center, 100 West Randolph Street, Suite 14- 600, Chicago, Illinois, the Stratton Office Building, 401 South Spring Street, Third Floor, Springfield, Illinois and the Illinois Department of Transportation Office, 1102 East Port Plaza, Collinsville, Illinois. The following Board Members were present: Chicago Collinsville Stewart Muñoz, Acting Chairman Glyn Ramage Miles Beatty, III Anthony Garippo William A. Lowry, Sr. Others present: Chicago Springfield Jim Underwood, CDB Amber Evans, CDB Karla Springer, CDB Gary Kitchen, CDB Ron Wright, CDB Lisa Mattingly, CDB Michael Bryant, Farnsworth Group Chris MacGibbon, CDB Phil Houser, Farnsworth Group Paula Sorensen, CDB Jesse Martinez, CDB Claudia André, CDB Andrea Bauer, CDB Amy Romano, CDB Kenneth Newman Josh Weger, CDB Adrienne Levatino, CDB Don Broughton, CDB Steve Petersen, Harper College Kyle Beachy, CDB Joseph Vitowsky, U of I Marcy Joerger, CDB Carolina Lopez, SmithGroupJJR Gus Behnke, CDB Dave Bodenschatz, KJWW Ann Tranter, FGM Architects Collinsville Al Perla, Primera Ron Henderson, SWIC Marva Boyd, CDB Bernie Ysursa, SWIC James Cockrell, CDB Mike Wilson, CDB Shannon Bookey, CDB Emilija Zgonjanin, CDB In Chairman O’Brien’s absence, member Stewart Muñoz chaired the meeting. Acting Chairman Muñoz called the meeting to order at 10:39 a.m. Amber Evans took roll call. For the record, Acting Chairman Stewart Muñoz and members Anthony Garippo, Miles Beatty and William Lowry were present at the Chicago meeting site. Member Glyn Ramage was present at the Collinsville meeting site.