The Impact of Political Uncertainty on Small-Business Behavior in Uganda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 5 Traffic Survey and Traffic Demand Forecast

Final Report – Executive Summary The Study on Greater Kampala Road Network and Transport Improvement in the Republic of Uganda November 2010 CHAPTER 5 TRAFFIC SURVEY AND TRAFFIC DEMAND FORECAST 5.1 TRAFFIC SURVEY The Study Team conducted a traffic survey in January 2010 to identify the current traffic condition and to forecast the future traffic demand. A supplemental traffic survey was also conducted on major junctions in June 2010 to study the current intersection condition and problems. The objective, method and coverage of six types of traffic survey are summarized as below: Table 5.1.1 Outline of Traffic Survey Survey Objectives Method Coverage To obtain traffic volumes on 12 locations (12hr) Traffic Count Survey Vehicular Traffic Count major roads 2 locations (24hr) Origin-Destination (O-D) To capture trip information of Interview with drivers at 9 locations Survey vehicles roadsides To obtain traffic volumes and Intersection Traffic Count movement at major Vehicular Traffic Count 2 locations Survey intersections To collect information about Taxi (Minibus) Passenger and Interview with taxi public transport driver and 5 major taxi parks Driver Interview Survey drivers and users users, and their opinions Boda-Boda (Bike Taxi) To collect information about Interview with boda-boda 6 areas on major Passenger and Driver boda-boda drivers and users, drivers and users roads Interview Survey and their opinions To collect information on Actual driving survey by Travel Speed Survey present traffic situation on passenger car major roads Source: JICA Study Team Actual traffic survey was conducted from January to February 2010. Each type of survey schedule is shown in below figure: 2009 2010 Survey Dec. -

The EIA Process in Uganda 63 Figure 9-1: Flow Chart Highlighting the Main Steps in the Environmental & Social Management Framework (ESMF) 109

DECEMBER 2013 Public Disclosure Authorized Republic of Uganda Uganda National Roads Authority NORTH EASTERN CORRIDOR ROAD ASSET MANAGEMENT PROJECT Public Disclosure Authorized (NECRAMP) - TORORO-MBALE- SOROTI-LIRA- KAMDINI ROAD ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL MANAGEMENT FRAMEWORK ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL MANAGEMENT FRAMEWORK Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized ADDRESS C O WI A /S P arallelvej 2 2800 Kongens Lyngby Denmark TEL +4 5 5 6 4 0 0 0 0 0 FAX +4 5 5 6 4 0 9 9 9 9 WWW c owi.c om DECEMBER 2013 UGANDA NATIONAL ROADS AUTHORITY NORTH EASTERN CORRIDOR ROAD ASSET MANAGEMENT PROJECT (NECRAMP) - TORORO-MBALE- SOROTI-LIRA-KAMDINI ROAD ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL MANAGEMENT FRAMEWORK PROJECT NO. A 0 1 3 6 9 3 DOCUMENT NO. 13693/ESMF VERSION 6 DATE OF ISSUE 3 Dec ember 2013 PREPARED RE M E /P A AO CHECKED DRS APPROVED MVJ i E nvironment and Soc ial Management Framework for T ororo-Mbale-Soroti-Lira-Kamdini Road (340 km) BASIC INFORMATION Basic Project Information Country: Uganda Project ID: P125590 Project Name: North Eastern Corridor Road Asset Management Project (NECRAMP) Task Team Negede Lewi Leader: Estimated 13-Jan-2014 Estimated 10-Jun-2014 Appraisal Board Date: ManagingDate: AFTTR Lending Specific Investment Loan Unit: Instrument: Sector(s): Rural and Inter-Urban Roads and Highways (80%), Public administration- Transportation (10%), General transportation sector Theme(s): Infrastructure(10%) services for private sector development (50%), Regional integration (20%), Rural services and infrastructure (20%), Administrative -

Kampala Cholera Situation Report

Kampala Cholera Situation Report Date: Monday 4th February, 2019 1. Summary Statistics No Summary of cases Total Number Total Cholera suspects- Cummulative since start of 54 #1 outbreak on 2nd January 2019 1 New case(s) suspected 04 2 New cases(s) confirmed 54 Cummulative confirmed cases 22 New Deaths 01 #2 3 New deaths in Suspected 01 4 New deaths in Confirmed 00 5 Cumulative cases (Suspected & confirmed cases) 54 6 Cumulative deaths (Supected & confirmed cases) in Health Facilities 00 Community 03 7 Total number of cases on admission 00 8 Cummulative cases discharged 39 9 Cummulative Runaways from isolation (CTC) 07 #3 10 Number of contacts listed 93 11 Total contacts that completed 9 day follow-up 90 12 Contacts under follow-up 03 13 Total number of contacts followed up today 03 14 Current admissions of Health Care Workers 00 13 Cummulative cases of Health Care Workers 00 14 Cummulative deaths of Health Care Workers 00 15 Specimens collected and sent to CPHL today 04 16 Cumulative specimens collected 45 17 Cummulative cases with lab. confirmation (acute) 00 Cummulative cases with lab. confirmation (convalescent) 22 18 Date of admission of last confirmed case 01/02/2019 19 Date of discharge of last confirmed case 02/02/2019 20 Confirmed cases that have died 1 (Died from the community) #1 The identified areas are Kamwokya Central Division, Mutudwe Rubaga, Kitintale Zone 10 Nakawa, Naguru - Kasende Nakawa, Kasanga Makindye, Kalambi Bulaga Wakiso, Banda Zone B3, Luzira Kamwanyi, Ndeba-Kironde, Katagwe Kamila Subconty Luwero District, -

World Bank Document

Document of The World Bank Public Disclosure Authorized Report No: ICR00002916 IMPLEMENTATION COMPLETION AND RESULTS REPORT (IDA-43670) ON A CREDIT Public Disclosure Authorized IN THE AMOUNT OF SDR 22.0 MILLION (US$ 33.6 MILLION EQUIVALENT) TO THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA FOR A KAMPALA INSTITUTIONAL AND INFRASTRUCTURE DEVELOPMENT ADAPTABLE PROGRAM LOAN (APL) PROJECT Public Disclosure Authorized June 27, 2014 Public Disclosure Authorized Urban Development & Services Practice 1 (AFTU1) Country Department AFCE1 Africa Region CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (Exchange Rate Effective July 31, 2007) Currency Unit = Uganda Shillings (Ushs) Ushs 1.00 = US$ 0.0005 US$ 1.53 = SDR 1 FISCAL YEAR July 1 – June 30 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS APL Adaptable Program Loan CAS Country Assistance Strategy CRCS Citizens Report Card Surveys CSOs Civil Society Organizations EA Environmental Analysis EIRR Economic Internal Rate of Return EMP Environment Management Plan FA Financing Agreement FRAP Financial recovery action plan GAAP Governance Assessment and Action Plan GAC Governance and Anti-corruption GoU Government of Uganda HDM-4 Highway Development and Management Model HR Human Resource ICR Implementation Completion Report IDA International Development Association IPF Investment Project Financing IPPS Integrated Personnel and Payroll System ISM Implementation Support Missions ISR Implementation Supervision Report KCC Kampala City Council KCCA Kampala Capital City Authority KDMP Kampala Drainage Master Plan KIIDP Kampala Institutional and Infrastructure Development Project -

View/Download

Research Article Food Science & Nutrition Research Risk Factors to Persistent Dysentery among Children under the Age of Five in Rural Sub-Saharan Africa; the Case of Kumi, Eastern Uganda Peter Kirabira1*, David Omondi Okeyo2, and John C. Ssempebwa3 1MD, MPH; Clarke International University, Kampala, Uganda. *Correspondence: 2PhD; School of Public Health, Department of Nutrition and Peter Kirabira, Clarke International University, P.O Box 7782, Health, Maseno University, Maseno Township, Kenya. Kampala, Uganda, Tel: +256 772 627 554; E-mail: drpkirabs@ gmail.com; [email protected]. 3MD, MPH, PhD; Disease Control and Environmental Health Department, School of Public Health, College of Health Sciences, Received: 02 July 2018; Accepted: 13 August 2018 Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda. Citation: Peter Kirabira, David Omondi Okeyo, John C Ssempebwa. Risk Factors to Persistent Dysentery among Children under the Age of Five in Rural Sub-Saharan Africa; the Case of Kumi, Eastern Uganda. Food Sci Nutr Res. 2018; 1(1): 1-6. ABSTRACT Introduction: Dysentery, otherwise called bloody diarrhoea, is a problem of Public Health importance globally, contributing 54% of the cases of childhood diarrhoeal diseases in Kumi district, Uganda. We set out to assess the risk factors associated with the persistently high prevalence of childhood dysentery in Kumi district. Methods: We conducted an analytical matched case-control study, with the under five child as the study unit. We collected quantitative data from the mothers or caretakers of the under five children using semi-structured questionnaires and checklists and qualitative data using Key informer interview guides. Quantitative data was analysed using SPSS while qualitative data was analysed manually. -

Healthy City Harvests

Urban Harvest is the CGIAR system wide initiative in urban and peri-urban agriculture, which aims to contribute to the food security of poor urban Healthy city harvests: families, and to increase the value of agricultural production in urban and peri-urban areas, while ensuring the sustainable management of the Generating evidence to guide urban environment. Urban Harvest is hosted and convened by the policy on urban agriculture International Potato Center. URBAN Editors: Donald Cole • Diana Lee-Smith • George Nasinyama HARVEST e r u t l u From its establishment as a colonial technical school in 1922, Makerere c i r University has become one of the oldest and most respected centers of g a higher learning in East Africa. Makerere University Press (MUP) was n a b inaugurated in 1994 to promote scholarship and publish the academic r u achievements of the university. It is being re-vitalised to position itself as a n o y powerhouse in publishing in the region. c i l o p e d i u g o t e c n e d i v e g n i t a r e n e G : s t s e v r a h y t i c y h t l a e H Av. La Molina 1895, La Molina, Lima Peru Makerere University Press Tel: 349 6017 Ext 2040/42 P.O. Box 7062, Kampala, Uganda email: [email protected] Tel: 256 41 532631 URBAN HARVEST www.uharvest.org Website: http://mak.ac.ug/ Healthy city harvests: Generating evidence to guide policy on urban agriculture URBAN Editors: Donald Cole • Diana Lee-Smith • George Nasinyama HARVEST Healthy city harvests: Generating evidence to guide policy on urban agriculture © International Potato Center (CIP) and Makerere University Press, 2008 ISBN 978-92-9060-355-9 The publications of Urban Harvest and Makerere University Press contribute important information for the public domain. -

Planned Shutdown Web October 2020.Indd

PLANNED SHUTDOWN FOR SEPTEMBER 2020 SYSTEM IMPROVEMENT AND ROUTINE MAINTENANCE REGION DAY DATE SUBSTATION FEEDER/PLANT PLANNED WORK DISTRICT AREAS & CUSTOMERS TO BE AFFECTED Kampala West Saturday 3rd October 2020 Mutundwe Kampala South 1 33kV Replacement of rotten vertical section at SAFARI gardens Najja Najja Non and completion of flying angle at MUKUTANO mutundwe. North Eastern Saturday 3rd October 2020 Tororo Main Mbale 1 33kV Create Two Tee-offs at Namicero Village MBALE Bubulo T/C, Bududa Tc Bulukyeke, Naisu, Bukigayi, Kufu, Bugobero, Bupoto Namisindwa, Magale, Namutembi Kampala West Sunday 4th October 2020 Kampala North 132/33kV 32/40MVA TX2 Routine Maintenance of 132/33kV 32/40MVA TX 2 Wandegeya Hilton Hotel, Nsooda Atc Mast, Kawempe Hariss International, Kawempe Town, Spencon,Kyadondo, Tula Rd, Ngondwe Feeds, Jinja Kawempe, Maganjo, Kagoma, Kidokolo, Kawempe Mbogo, Kalerwe, Elisa Zone, Kanyanya, Bahai, Kitala Taso, Kilokole, Namere, Lusanjja, Kitezi, Katalemwa Estates, Komamboga, Mambule Rd, Bwaise Tc, Kazo, Nabweru Rd, Lugoba Kazinga, Mawanda Rd, East Nsooba, Kyebando, Tilupati Industrial Park, Mulago Hill, Turfnel Drive, Tagole Cresent, Kamwokya, Kubiri Gayaza Rd, Katanga, Wandegeya Byashara Street, Wandegaya Tc, Bombo Rd, Makerere University, Veterans Mkt, Mulago Hospital, Makerere Kavule, Makerere Kikumikikumi, Makerere Kikoni, Mulago, Nalweuba Zone Kampala East Sunday 4th October 2020 Jinja Industrial Walukuba 11kV Feeder Jinja Industrial 11kV feeders upgrade JINJA Walukuba Village Area, Masese, National Water Kampala East -

The Rural Non-Farm Economy in Uganda: a Review of Policy (NRI Report No

The rural non-farm economy in Uganda: a review of policy (NRI report no. 2702) Greenwich Academic Literature Archive (GALA) Citation: Marter, Alan (2002) The rural non-farm economy in Uganda: a review of policy (NRI report no. 2702). [Working Paper] Available at: http://gala.gre.ac.uk/11656 Copyright Status: Permission is granted by the Natural Resources Institute (NRI), University of Greenwich for the copying, distribution and/or transmitting of this work under the conditions that it is attributed in the manner specified by the author or licensor and it is not used for commercial purposes. However you may not alter, transform or build upon this work. Please note that any of the aforementioned conditions can be waived with permission from the NRI. Where the work or any of its elements is in the public domain under applicable law, that status is in no way affected by this license. This license in no way affects your fair dealing or fair use rights, or other applicable copyright exemptions and limitations and neither does it affect the author’s moral rights or the rights other persons may have either in the work itself or in how the work is used, such as publicity or privacy rights. For any reuse or distribution, you must make it clear to others the license terms of this work. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. Contact: GALA Repository Team: [email protected] Natural Resources Institute: [email protected] NATURAL RESOURCES INSTITUTE NRI Report No. 2702 Rural Non-Farm Economy The Rural Non-Farm Economy in Uganda: A Review of Policy by Alan Marter September 2002 The views expressed in this document are solely those of the author and not necessarily those of DFID or the World Bank World Bank Preface The importance of the Rural Non-Farm Economy (RNFE) is reflected in the rural development strategies of many organisations. -

Nakawa Division Grades

DIVISION PARISH VILLAGE STREET AREA GRADE NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BLOCK 1 TO24 LUTHULI 4TH CLOSE 2-9 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BLOCK 1 TO25 LUTHULI 1ST CLOSE 1-9 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BLOCK 1 TO26 LUTHULI 5TH CLOSE 1-9 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BLOCK 1 TO27 LUTHULI 2ND CLOSE 1-10 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BLOCK 1 TO28 LUTHULI RISE 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW II MBUYA ROAD 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW II MIZINDALO ROAD 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW II MPANGA CLOSE 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW II MUZIWAACO ROAD 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW II PRINCESS ANNE DRIVE 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW II ROBERT MUGABE ROAD. 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW II BAZARRABUSA DRIVE 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW II BINAYOMBA RISE 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW II BINAYOMBA ROAD 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW II BUGOLOBI STREET 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW II FARADAY ROAD 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW II FARADY ROAD 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW II HUNTER CLOSE 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW II KULUBYA CLOSE 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW I BANDALI RISE 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW I HANLON ROAD 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW I MUWESI ROAD 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW I NYONDO CLOSE 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW I SALMON RISE 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW I SPRING ROAD 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW I YOUNGER AVENUE 1 NAKAWA BUKOTO I KALONDA KISASI ROAD 1 NAKAWA BUKOTO I KALONDA SERUMAGA ROAD 1 NAKAWA BUKOTO I MUKALAZI KISASI ROAD 1 NAKAWA BUKOTO I MUKALAZI MUKALAZI ROAD 1 1 NAKAWA BUKOTO I MULIMIRA OFF MOYO CLOSE 1 NAKAWA BUKOTO I NTINDA- OLD KIRA ZONE NTINDA- OLD KIRA ROAD 1 NAKAWA BUKOTO I OLD KIRA ROAD BATAKA ROAD 1 NAKAWA BUKOTO I OLD KIRA ROAD LUTAYA -

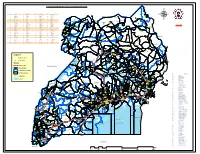

Legend " Wanseko " 159 !

CONSTITUENT MAP FOR UGANDA_ELECTORAL AREAS 2016 CONSTITUENT MAP FOR UGANDA GAZETTED ELECTORAL AREAS FOR 2016 GENERAL ELECTIONS CODE CONSTITUENCY CODE CONSTITUENCY CODE CONSTITUENCY CODE CONSTITUENCY 266 LAMWO CTY 51 TOROMA CTY 101 BULAMOGI CTY 154 ERUTR CTY NORTH 165 KOBOKO MC 52 KABERAMAIDO CTY 102 KIGULU CTY SOUTH 155 DOKOLO SOUTH CTY Pirre 1 BUSIRO CTY EST 53 SERERE CTY 103 KIGULU CTY NORTH 156 DOKOLO NORTH CTY !. Agoro 2 BUSIRO CTY NORTH 54 KASILO CTY 104 IGANGA MC 157 MOROTO CTY !. 58 3 BUSIRO CTY SOUTH 55 KACHUMBALU CTY 105 BUGWERI CTY 158 AJURI CTY SOUTH SUDAN Morungole 4 KYADDONDO CTY EST 56 BUKEDEA CTY 106 BUNYA CTY EST 159 KOLE SOUTH CTY Metuli Lotuturu !. !. Kimion 5 KYADDONDO CTY NORTH 57 DODOTH WEST CTY 107 BUNYA CTY SOUTH 160 KOLE NORTH CTY !. "57 !. 6 KIIRA MC 58 DODOTH EST CTY 108 BUNYA CTY WEST 161 OYAM CTY SOUTH Apok !. 7 EBB MC 59 TEPETH CTY 109 BUNGOKHO CTY SOUTH 162 OYAM CTY NORTH 8 MUKONO CTY SOUTH 60 MOROTO MC 110 BUNGOKHO CTY NORTH 163 KOBOKO MC 173 " 9 MUKONO CTY NORTH 61 MATHENUKO CTY 111 MBALE MC 164 VURA CTY 180 Madi Opei Loitanit Midigo Kaabong 10 NAKIFUMA CTY 62 PIAN CTY 112 KABALE MC 165 UPPER MADI CTY NIMULE Lokung Paloga !. !. µ !. "!. 11 BUIKWE CTY WEST 63 CHEKWIL CTY 113 MITYANA CTY SOUTH 166 TEREGO EST CTY Dufile "!. !. LAMWO !. KAABONG 177 YUMBE Nimule " Akilok 12 BUIKWE CTY SOUTH 64 BAMBA CTY 114 MITYANA CTY NORTH 168 ARUA MC Rumogi MOYO !. !. Oraba Ludara !. " Karenga 13 BUIKWE CTY NORTH 65 BUGHENDERA CTY 115 BUSUJJU 169 LOWER MADI CTY !. -

Rethinking Peace and Conflict Studies

Rethinking Peace and Conflict Studies Series Editor: Oliver P. Richmond, Professor, School of International Relations, University of St Andrews Editorial Board: Roland Bleiker, University of Queensland, Australia; Henry F. Carey, Georgia State University, USA; Costas Constantinou, University of Keele, UK; A.J.R. Groom, University of Kent, UK; Vivienne Jabri, King’s College London, UK; Edward Newman, University of Birmingham, UK; Sorpong Peou, Sophia University, Japan; Caroline Kennedy-Pipe, University of Sheffield, UK; Professor Michael Pugh, University of Bradford, UK; Chandra Sriram, University of East London, UK; Ian Taylor, University of St Andrews, UK; Alison Watson, University of St Andrews, UK; R.B.J. Walker, University of Victoria, Canada; Andrew Williams, University of St Andrews, UK. Titles include: Susanne Buckley-Zistel CONFLICT TRANSFORMATION AND SOCIAL CHANGE IN UGANDA Remembering after Violence Jason Franks RETHINKING THE ROOTS OF TERRORISM Vivienne Jabri WAR AND THE TRANSFORMATION OF GLOBAL POLITICS James Ker-Lindsay EU ACCESSION AND UN PEACEKEEPING IN CYPRUS Roger MacGinty NO WAR, NO PEACE The Rejuvenation of Stalled Peace Processes and Peace Accords Carol McQueen HUMANITARIAN INTERVENTION AND SAFETY ZONES Iraq, Bosnia and Rwanda Sorpong Peou INTERNATIONAL DEMOCRACY ASSISTANCE FOR PEACEBUILDING The Cambodian Experience Sergei Prozorov UNDERSTANDING CONFLICT BETWEEN RUSSIA AND THE EU The Limits of Integration Oliver P. Richmond THE TRANSFORMATION OF PEACE Bahar Rumelili CONSTRUCTING REGIONAL AND GLOBAL ORDER Europe and Southeast Asia Chandra Lekha Sriram PEACE AS GOVERNANCE Stephan Stetter WORLD SOCIETY AND THE MIDDLE EAST Reconstructions in Regional Politics Rethinking Peace and Conflict Studies Series Standing Order ISBN 978--1--4039--9575--9 (hardback) & 978--1--4039--9576--6 (paperback) You can receive future titles in this series as they are published by placing a standing order. -

List of Bonded Warehouses in Uganda

List of Bonded Warehouses in Uganda 1.Atlas Cargo Systems BONDED WAREHOUSES Plot 1 Kireka Road/Sabuni Road, Mbuya Opp. Shell & Gaz Petro Stations P.O. Box 7765 Kampala 0414245 861/236 704/6/7/8 [email protected] 2. Space Registration BONDED WAREHOUSES Plot 2 Kyadondo Road Nakasero P.O. Box 3842 Kampala 0312276555, 0772640358 3. Cadam Enterprises Ltd BONDED WAREHOUSES Plot 4-6 Naguru Road Naguru P.O. Box 27627 Kampala 0414340 347/438, 0772412 704 4. Symbion Uganda Ltd. BONDED WAREHOUSES Plot 14 Parliament Avenue Jubilee Insurance Plaza, 7th Floor P.O. Box 7671 Kampala 0312260252, 0414251142 5. General Agencies (U) Ltd BONDED WAREHOUSES Plot 1 7th Street, Industrial Area P.O. Box 23013 Kampala 414255 52/95 6. Bureau Veritas Uganda BONDED WAREHOUSES Plot 30 Lugogo By pass P.O BOX 40323 Kampala 0792280280, 0792280281 http://www.bureauveritas.com 7. Multiple ICD BONDED WAREHOUSES Plot M612 Ntinda RoadNtinda Industrial Area P.O. Box 28884 Kampala 414288 35/71 [email protected] 8. Intertek International Ltd BONDED WAREHOUSES Plot 3-5 port bell road 0414230990, 0414231990 info@[email protected] http://www.intertek.com 9. SDV Transami (U) Ltd BONDED WAREHOUSES Plot M-611 Ntinda Road Ntinda Industrial Area P.O. Box 5501 Kampala 0414336 000, 0312-211 000 [email protected] 10. Uganda National Bureau of Standards (UNBS) BONDED WAREHOUSES Bweyogelele Branch P.O BOX 6329 Kampala 0414222367, 0414505995 [email protected] http://www.unbs.go.ug 11. Maersk Uganda Ltd BONDED WAREHOUSES 5th Street, Industrial Area P.O. Box 28687 Kampala 414433 7/8 [email protected] 12.