Factors Preventing Wide-Scope Coverage of the Iraq War by Embedded Reporters—From “Shock and Awe” to “Mission Accomplished” (March 21 - May 1, 2003)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Does Policy Lead Media Coverage?

Does Policy Lead Mainstream Media? How Sources Framed the 2011 Egyptian Protests by Kristen E. Grimmer Submitted to the William Allen White School of Journalism and Mass Communication and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science ________________________________________ Scott Reinardy Associate Professor Chairperson Committee Members# ________________________________________* Barbara Barnett Associate Dean for Undergraduate Studies _______________________________________* Doug Ward Associate Professor Date defended: ___04/09/2012________ ii The Thesis Committee for (Kristen E. Grimmer) certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Does Policy Lead Mainstream Media? How Sources Framed the 2011 Egyptian Conflict Committee: ____________________________ Scott Reinardy, Associate Professor Chairperson* Barbara Barnett, Associate Dean Doug Ward, Associate Professor Date approved: __05/01/2012__ iii Abstract This study uses a quantitative content analysis to determine the framing used by U.S. mainstream newspapers in media coverage of the 2011 Egyptian protests. The study examined 153 stories from The New York Times and The Washington Post. The study focuses on how sources framed the protests, former President Hosni Mubarak, and the effects the protests had on both Egypt and the United States. The analysis reveals that the viewpoints of U.S. official sources were overrepresented in news coverage and framed the conflict overall in a neutral -

The Rules of #Metoo

University of Chicago Legal Forum Volume 2019 Article 3 2019 The Rules of #MeToo Jessica A. Clarke Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Clarke, Jessica A. (2019) "The Rules of #MeToo," University of Chicago Legal Forum: Vol. 2019 , Article 3. Available at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf/vol2019/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Chicago Legal Forum by an authorized editor of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Rules of #MeToo Jessica A. Clarke† ABSTRACT Two revelations are central to the meaning of the #MeToo movement. First, sexual harassment and assault are ubiquitous. And second, traditional legal procedures have failed to redress these problems. In the absence of effective formal legal pro- cedures, a set of ad hoc processes have emerged for managing claims of sexual har- assment and assault against persons in high-level positions in business, media, and government. This Article sketches out the features of this informal process, in which journalists expose misconduct and employers, voters, audiences, consumers, or professional organizations are called upon to remove the accused from a position of power. Although this process exists largely in the shadow of the law, it has at- tracted criticisms in a legal register. President Trump tapped into a vein of popular backlash against the #MeToo movement in arguing that it is “a very scary time for young men in America” because “somebody could accuse you of something and you’re automatically guilty.” Yet this is not an apt characterization of #MeToo’s paradigm cases. -

Wye River Memorandum: a Transition to Final Peace Justus R

Hastings International and Comparative Law Review Volume 24 Article 1 Number 1 Fall 2000 1-1-2000 Wye River Memorandum: A Transition to Final Peace Justus R. Weiner Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/ hastings_international_comparative_law_review Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, and the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Justus R. Weiner, Wye River Memorandum: A Transition to Final Peace, 24 Hastings Int'l & Comp. L. Rev. 1 (2000). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_international_comparative_law_review/vol24/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings International and Comparative Law Review by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Wye River Memorandum: A Transition to Final Peace? BY JusTus R. WEINER* Table of Contents Introduction ...........................................................................................2 I. Inception of the Wye River Memorandum .................................5 A. The Memorandum's Position in the Peace Process ............. 5 B. The Terms Agreed Upon ........................................................8 1. The Wye River Memorandum and Related Letters from the United States .....................................................8 2. The Intricate "Time Line".............................................. 9 -

CNN Communications Press Contacts Press

CNN Communications Press Contacts Allison Gollust, EVP, & Chief Marketing Officer, CNN Worldwide [email protected] ___________________________________ CNN/U.S. Communications Barbara Levin, Vice President ([email protected]; @ blevinCNN) CNN Digital Worldwide, Great Big Story & Beme News Communications Matt Dornic, Vice President ([email protected], @mdornic) HLN Communications Alison Rudnick, Vice President ([email protected], @arudnickHLN) ___________________________________ Press Representatives (alphabetical order): Heather Brown, Senior Press Manager ([email protected], @hlaurenbrown) CNN Original Series: The History of Comedy, United Shades of America with W. Kamau Bell, This is Life with Lisa Ling, The Nineties, Declassified: Untold Stories of American Spies, Finding Jesus, The Radical Story of Patty Hearst Blair Cofield, Publicist ([email protected], @ blaircofield) CNN Newsroom with Fredricka Whitfield New Day Weekend with Christi Paul and Victor Blackwell Smerconish CNN Newsroom Weekend with Ana Cabrera CNN Atlanta, Miami and Dallas Bureaus and correspondents Breaking News Lauren Cone, Senior Press Manager ([email protected], @lconeCNN) CNN International programming and anchors CNNI correspondents CNN Newsroom with Isha Sesay and John Vause Richard Quest Jennifer Dargan, Director ([email protected]) CNN Films and CNN Films Presents Fareed Zakaria GPS Pam Gomez, Manager ([email protected], @pamelamgomez) Erin Burnett Outfront CNN Newsroom with Brooke Baldwin Poppy -

Finding Aid to the Historymakers ® Video Oral History with Soledad O'brien

Finding Aid to The HistoryMakers ® Video Oral History with Soledad O'Brien Overview of the Collection Repository: The HistoryMakers®1900 S. Michigan Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60616 [email protected] www.thehistorymakers.com Creator: O’Brien, Soledad, 1966- Title: The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History Interview with Soledad O'Brien, Dates: February 21, 2014 Bulk Dates: 2014 Physical 6 uncompressed MOV digital video files (2:42:12). Description: Abstract: Broadcast journalist Soledad O'Brien (1966 - ) founded the Starfish Media Group, and anchored national television news programs like NBC’s The Site and American Morning, and CNN’s In America. O'Brien was interviewed by The HistoryMakers® on February 21, 2014, in New York, New York. This collection is comprised of the original video footage of the interview. Identification: A2014_055 Language: The interview and records are in English. Biographical Note by The HistoryMakers® Broadcast journalist Soledad O’Brien was born on September 19, 1966 in Saint James, New York. Her father, Edward, was a mechanical engineering professor; her mother, Estela, a French and English teacher. O’Brien graduated from Smithtown High School East in 1984, and went on to attend Harvard University from 1984 to 1988, but did not graduate until 2000, when she received her B.A. degree in English and American literature. In 1989, O’Brien began her career at KISS-FM in Boston, Massachusetts as a reporter for the medical talk show Second Opinion and of Health Week in Review. In 1990, she was hired as an associate producer and news writer for Boston’s WBZ-TV station. O’Brien then worked at NBC News in New York City in 1991, as a field producer for Nightly News and Today, before being hired at San Francisco’s NBC affiliate KRON in 1993, where she worked as a reporter and bureau chief and co-hosted the Discovery Channel’s The Know Zone. -

Cuaderno De Documentacion

SECRETARIA DE ESTADO DE ECONOMÍA, MINISTERIO DIRECCIÓN GENERAL DE POLÍTICA ECONÓMICA DE ECONOMÍA SUBDIRECCIÓN GENERAL DE ECONOMÍA INTERNACIONAL CUADERNO DE DOCUMENTACION Número 43 Alvaro Espina Vocal Asesor 22 de Abril 2003 CUADERNO DE DOCUMENTACIÓN 22042003 43 Guerra de Irak: (VIII) 1.- Foreign Affairs May/June 2003, Vol 82, Number 3. Issue Highlight: “The Rise of Ethics in Foreign Policy: Reaching a Values Consensus” by Leslie H. Gelb and Justine A. Rosenthal "Why the Security Council Failed" by Michael Glennon “How to Build a Democratic Iraq” By Adeed Dawisha and Karen Dawisha “A Trusteeship for Palestine?” Martin Indyk “Is Turkey Ready for Europe?” by Michael S. Teitelbaum and Philip L. Martin ………………………………………………………………………………………Página 3 2.- Informe completo días 10, 11, 14, 16 y 17 de abril - April 17, 2003 MIDEAST ROADMAP: IRAQ WAR OPENS 'WINDOW OF OPPORTUNITY' FOR PEACE .………………………………………….. Página 9 - April 16, 2003 IRAQ: THE HUNT FOR 'STUBBORNLY ELUSIVE' WMD…P. 27 - April 14, 2003 POST-IRAQ: SYRIA IS LIKELY 'NEXT VICTIM' OF U.S. 'IMPERIALISM' ……………………………………………………………Página 40 - April 10, 2003 DEATHS OF JOURNALISTS: SUSPICION U.S. ATTACKS WERE 'NO ACCIDENT' 1,? ……………………………………………...…... Página 61 - April 10, 2003 FALL OF BAGHDAD 'IMPRESSIVE' BUT 'TROUBLING' ………………………………………………………………………... Página 76 3.- Brookings Iraq Reports días 10, 11, 12, 14, 15, 16 y 18 de abril ............................................................. ........................Página 99 1 TheNew National Security Strategy: Focus on Failed States by Susan E. Rice………………………………………………………… Página 111 4.- American Outlook Today, días 15, y 16 de abril …...................................................………… Página 117 5.- San Francisco Chronicle, The pictures of the war ……….................................................................. Página 123 “Plan for democracy in Iraq may be folly. Experts also question U.S. -

DA Spring 03

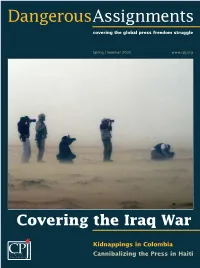

DangerousAssignments covering the global press freedom struggle Spring | Summer 2003 www.cpj.org Covering the Iraq War Kidnappings in Colombia Committee to·Protect Cannibalizing the Press in Haiti Journalists CONTENTS Dangerous Assignments Spring|Summer 2003 Committee to Protect Journalists FROM THE EDITOR By Susan Ellingwood Executive Director: Ann Cooper History in the making. 2 Deputy Director: Joel Simon IN FOCUS By Amanda Watson-Boles Dangerous Assignments Cameraman Nazih Darwazeh was busy filming in the West Bank. Editor: Susan Ellingwood Minutes later, he was dead. What happened? . 3 Deputy Editor: Amanda Watson-Boles Designer: Virginia Anstett AS IT HAPPENED By Amanda Watson-Boles Printer: Photo Arts Limited A prescient Chinese free-lancer disappears • Bolivian journalists are Committee to Protect Journalists attacked during riots • CPJ appeals to Rumsfeld • Serbia hamstrings Board of Directors the media after a national tragedy. 4 Honorary Co-Chairmen: CPJ REMEMBERS Walter Cronkite Our fallen colleagues in Iraq. 6 Terry Anderson Chairman: David Laventhol COVERING THE IRAQ WAR 8 Franz Allina, Peter Arnett, Tom Why I’m Still Alive By Rob Collier Brokaw, Geraldine Fabrikant, Josh A San Francisco Chronicle reporter recounts his days and nights Friedman, Anne Garrels, James C. covering the war in Baghdad. Goodale, Cheryl Gould, Karen Elliott House, Charlayne Hunter- Was I Manipulated? By Alex Quade Gault, Alberto Ibargüen, Gwen Ifill, Walter Isaacson, Steven L. Isenberg, An embedded CNN reporter reveals who pulled the strings behind Jane Kramer, Anthony Lewis, her camera. David Marash, Kati Marton, Michael Massing, Victor Navasky, Frank del Why I Wasn’t Embedded By Mike Kirsch Olmo, Burl Osborne, Charles A CBS correspondent explains why he chose to go it alone. -

Intimate Perspectives from the Battlefields of Iraq

'The Best Covered War in History': Intimate Perspectives from the Battlefields of Iraq by Andrew J. McLaughlin A thesis presented to the University Of Waterloo in fulfilment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2017 © Andrew J. McLaughlin 2017 Examining Committee Membership The following served on the Examining Committee for this thesis. The decision of the Examining Committee is by majority vote. External Examiner Marco Rimanelli Professor, St. Leo University Supervisor(s) Andrew Hunt Professor, University of Waterloo Internal Member Jasmin Habib Associate Professor, University of Waterloo Internal Member Roger Sarty Professor, Wilfrid Laurier University Internal-external Member Brian Orend Professor, University of Waterloo ii Author's Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. iii Abstract This study examines combat operations from the 2003 invasion of Iraq War from the “ground up.” It utilizes unique first-person accounts that offer insights into the realities of modern warfare which include effects on soldiers, the local population, and journalists who were tasked with reporting on the action. It affirms the value of media embedding to the historian, as hundreds of journalists witnessed major combat operations firsthand. This line of argument stands in stark contrast to other academic assessments of the embedding program, which have criticized it by claiming media bias and military censorship. Here, an examination of the cultural and social dynamics of an army at war provides agency to soldiers, combat reporters, and innocent civilians caught in the crossfire. -

The Archive of American Journalism Ray Stannard Baker Collection

The Archive of American Journalism Ray Stannard Baker Collection McClure’s Magazine September, 1898 How the News of the War is Reported WAR with Spain began, so far as the newspapers were concerned, when the “Maine” was blown up in Havana harbor. The explosion occurred at 9.40 o’clock on the evening of February 15, 1898. At half-past two on the following morning the first reports, filed by the correspondents in Havana, reached New York, and at daylight newsboys in every city in America were crying the extras which gave the details of the disaster. Before noon on the 16th, a tug steamed out of the harbor at Key West with three divers on board. In the few hurried hours after the news reached New York “The World” had telegraphed its representative in Key West, and divers had been roused out of bed, had collected their paraphernalia, and had embarked on the newly chartered tug for Havana. Early in the afternoon, “The World” correspondent in Havana received the following cabled instructions: “Have sent divers to you from Key West to get actual truth, whether favorable or unfavorable. First investigation by divers, with authentic results, worth $1,000 extra expense tomorrow alone.” But when the divers arrived, they were not allowed to make a descent, and all that the newspaper sponsors of the enterprise derived from the expedition was a bill of expense amounting to nearly $1,000. This was the beginning. During the next few days scores of correspondents were rushed into Havana, and half a hundred great newspapers began to fill with news and pictures of the wreck. -

The Obama Administration and the Press Leak Investigations and Surveillance in Post-9/11 America

The Obama Administration and the Press Leak investigations and surveillance in post-9/11 America By Leonard Downie Jr. with reporting by Sara Rafsky A special report of the Committee to Protect Journalists Leak investigations and surveillance in post-9/11 America U.S. President Barack Obama came into office pledging open government, but he has fallen short of his promise. Journalists and transparency advocates say the White House curbs routine disclosure of information and deploys its own media to evade scrutiny by the press. Aggressive prosecution of leakers of classified information and broad electronic surveillance programs deter government sources from speaking to journalists. A CPJ special report by Leonard Downie Jr. with reporting by Sara Rafsky Barack Obama leaves a press conference in the East Room of the White House August 9. (AFP/Saul Loeb) Published October 10, 2013 WASHINGTON, D.C. In the Obama administration’s Washington, government officials are increasingly afraid to talk to the press. Those suspected of discussing with reporters anything that the government has classified as secret are subject to investigation, including lie-detector tests and scrutiny of their telephone and e-mail records. An “Insider Threat Program” being implemented in every government department requires all federal employees to help prevent unauthorized disclosures of information by monitoring the behavior of their colleagues. Six government employees, plus two contractors including Edward Snowden, have been subjects of felony criminal prosecutions since 2009 under the 1917 Espionage Act, accused of leaking classified information to the press— compared with a total of three such prosecutions in all previous U.S. -

Embedded Reporters: What Are Americans Getting?

Embedded Reporters: What Are Americans Getting? For More Information Contact: Tom Rosenstiel, Director, Project for Excellence in Journalism Amy Mitchell, Associate Director Matt Carlson, Wally Dean, Dante Chinni, Atiba Pertilla, Research Nancy Anderson, Tom Avila, Staff Embedded Reporters: What Are Americans Getting? Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld has suggested we are getting only “slices” of the war. Other observers have likened the media coverage to seeing the battlefield through “a soda straw.” The battle for Iraq is war as we’ve never it seen before. It is the first full-scale American military engagement in the age of the Internet, multiple cable channels and a mixed media culture that has stretched the definition of journalism. The most noted characteristic of the media coverage so far, however, is the new system of “embedding” some 600 journalists with American and British troops. What are Americans getting on television from this “embedded” reporting? How close to the action are the “embeds” getting? Who are they talking to? What are they talking about? To provide some framework for the discussion, the Project for Excellence in Journalism conducted a content analysis of the embedded reports on television during three of the first six days of the war. The Project is affiliated with Columbia University and funded by the Pew Charitable Trusts. The embedded coverage, the research found, is largely anecdotal. It’s both exciting and dull, combat focused, and mostly live and unedited. Much of it lacks context but it is usually rich in detail. It has all the virtues and vices of reporting only what you can see. -

Threat Report the State of Influence Operations 2017-2020

May 2021 Threat Report The State of Influence Operations 2017-2020 The State of Influence Operations 2017-2020 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary 3 Introduction 9 Section 1: Defining IO 11 Section 2: The State of IO, 2017- 2020 15 Threat actors 15 Trends in IO 19 Section 3: Targeting the US Ahead of the 2020 Election 28 Section 4: Countering IO 34 Combination of automation and investigations 34 Product innovation and adversarial design 36 Partnerships with industry, government and civil society 38 Building deterrence 39 Section 5: Conclusion 41 Appendix: List of CIB Disruptions, 2017-May 2021 44 Authors 45 The State of Influence Operations 2017-2020 3 Executive Summary Over the past four years, industry, government and civil society have worked to build our collective response to influence operations (“IO”), which we define as “c oordinated efforts to manipulate or corrupt public debate for a strategic goal.” The security teams at Facebook have developed policies, automated detection tools, and enforcement frameworks to tackle deceptive actors — both foreign and domestic. Working with our industry peers, we’ve made progress against IO by making it less effective and by disrupting more campaigns early, before they could build an audience. These efforts have pressed threat actors to shift their tactics. They have — often without success — moved away from the major platforms and increased their operational security to stay under the radar. Historically, influence operations have manifested in different forms: from covert campaigns that rely on fake identities to overt, state-controlled media efforts that use authentic and influential voices to promote messages that may or may not be false.