A Report on the Current Environmental Condition of the North Norfolk Coast

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tourism Benefit & Impacts Analysis in the Norfolk Coast Area Of

TOURISM BENEFIT & IMPACTS ANALYSIS IN THE NORFOLK COAST AREA OF OUTSTANDING NATURAL BEAUTY APPENDICES May 2006 A Report for the Norfolk Coast Partnership Prepared by Scott Wilson NORFOLK COAST PARTNERSHIP TOURISM BENEFIT & IMPACTS ANALYSIS IN THE NORFOLK COAST AREA OF OUTSTANDING NATURAL BEAUTY APPENDICES May 2006 Prepared by Checked by Authorised by Scott Wilson Ltd 3 Foxcombe Court, Wyndyke Furlong, Abingdon Business Park, Abingdon Oxon, OX14 1DZ Tel: +44 (0) 1235 468700 Fax: +44 (0) 1235 468701 Norfolk Coast Partnership Tourism Benefit & Impacts Analysis in the Norfolk Coast AONB Scott Wilson Contents 1 A1 - Norfolk Coast Management ...............................................................1 2 A2 – Asset & Appeal Audit ......................................................................12 3 A3 - Tourism Plant Audit..........................................................................25 4 A4 - Market Context.................................................................................34 5 A5 - Economic Impact Assessment Calculations ....................................46 Norfolk Coast Partnership Tourism Benefit & Impacts Analysis in the Norfolk Coast AONB Scott Wilson Norfolk Coast AONB Tourism Impact Analysis – Appendices 1 A1 - Norfolk Coast Management 1.1 A key aspect of the Norfolk Coast is the array of authority, management and access organisations that actively participate, through one means or another, in the use and maintenance of the Norfolk Coast AONB, particularly its more fragile sites. 1.2 The aim of the -

Layman's Report

Titchwell Marsh Coastal Change Project Layman’s Report Introduction Titchwell Marsh RSPB Nature Reserve was created between 1974 and 1978. Today the Reserve covers 379 ha of the North Norfolk coastline and is one of the RSPB’s most popular nature reserves. The location of the reserve is illustrated below. Historical records show that by 1717 the land that is now occupied by the nature reserve had been claimed from the sea and for over 200 years was in agricultural use, as well as a short period of time as a military training area. Following the devastating east coast floods in 1953 the sea defences protecting the land were breached and never repaired. The land returned back to saltmarsh. In the 1970s, the RSPB acquired the site and enclosed 38 ha of the saltmarsh within a series of sea walls creating 11 ha of brackish (intermediate salinity) lagoon, 18 ha of freshwater reedbeds and 12 ha of freshwater lagoons. Combined with coastal dunes, saltmarsh, tidal reedbed and small stands of broad‐leaved woodland and scrub, Titchwell supports a wide range of habitats in a relatively small area. Titchwell Marsh is now of national and international importance for birds and other wildlife and is a component of two Natura 2000 sites ‐ the North Norfolk Coast Special Area of Conservation (SAC) and The North Norfolk Coast Special Protection Area (SPA). In addition Titchwell Marsh lies within the North Norfolk Coast Ramsar Site, the North Norfolk Coast Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) and the Norfolk Coast Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB).The reserve is noted, in particular, for the following: The second largest reedbed in North Norfolk, nationally important for breeding marsh harrier, bearded tit and bittern. -

WESTGATE FARM, Burnham Market, Norfolk WESTGATE FARM Ringstead Road, Burnham Market, Norfolk PE31 8JR

WESTGATE FARM, Burnham Market, Norfolk WESTGATE FARM Ringstead Road, Burnham Market, Norfolk PE31 8JR Brancaster 5 miles. Holkham Beach 6 miles. Wells-next-the-Sea 7.5 miles. King’s Lynn 23 miles. Norwich 37 miles. London King’s Cross 1hr 40 minutes by rail from King’s Lynn Introduction: Tenure and Possession: The sale of Westgate Farm provides interested parties with an exceptionally rare All the property included herein is to be offered freehold with the benefit of vacant opportunity to purchase a coastal smallholding with planning potential on the outskirts of possession subject to those rights of Holdover detailed herein. the much sought-after North Norfolk Village of Burnham Market. Viewing: Set in a ring-fence with spectacular views to all sides, the sale comprises Westgate Viewing is accompanied and strictly by prior appointment only with the Vendors’ Farm House, Greenfields Bungalow, a range of modern farm buildings and arable land Agents, Cruso & Wilkin. Tel. 01553 691691. amounting to 11.07 hectares. Health and Safety: PARTICULARS: Given the potential hazards of a working farm and for your own personal safety we Location and Situation: would ask you to be as vigilant as possible when making an inspection, particularly Burnham Market is a stunning Georgian village complete with Village Green, around farm machinery. We regret to advise that children and/or pets are not permitted surrounded by 18th Century houses together with shops, boutiques and on the farm when viewing. Public Houses including The Hoste Arms. The village has a range of essential amenities including a doctors and a dental surgery, pharmacy, primary school and post office together with a bakery, butcher, fresh fish shop, beauty salon and a range of clothing outfitters. -

Glaven Historian

the GLAVEN HISTORIAN No 16 2018 Editorial 2 Diana Cooke, John Darby: Land Surveyor in East Anglia in the late Sixteenth 3 Jonathan Hooton Century Nichola Harrison Adrian Marsden Seventeenth Century Tokens at Cley 11 John Wright North Norfolk from the Sea: Marine Charts before 1700 23 Jonathan Hooton William Allen: Weybourne ship owner 45 Serica East The Billyboy Ketch Bluejacket 54 Eric Hotblack The Charities of Christopher Ringer 57 Contributors 60 2 The Glaven Historian No.16 Editorial his issue of the Glaven Historian contains eight haven; Jonathan Hooton looks at the career of William papers and again demonstrates the wide range of Allen, a shipowner from Weybourne in the 19th cen- Tresearch undertaken by members of the Society tury, while Serica East has pulled together some his- and others. toric photographs of the Billyboy ketch Bluejacket, one In three linked articles, Diana Cooke, Jonathan of the last vessels to trade out of Blakeney harbour. Hooton and Nichola Harrison look at the work of John Lastly, Eric Hotblack looks at the charities established Darby, the pioneering Elizabethan land surveyor who by Christopher Ringer, who died in 1678, in several drew the 1586 map of Blakeney harbour, including parishes in the area. a discussion of how accurate his map was and an The next issue of Glaven Historian is planned for examination of the other maps produced by Darby. 2020. If anyone is considering contributing an article, Adrian Marsden discusses the Cley tradesmen who is- please contact the joint editor, Roger Bland sued tokens in the 1650s and 1660s, part of a larger ([email protected]). -

Hunstanton Neighbourhood Development Plan – Draft Version 4.2

Hunstanton Neighbourhood Development Plan – draft version 4.2 Introduction 1. Hunstanton’s Neighbourhood Development Plan (HNDP) has been modelled on a number of other parish neighbourhood plans with the intention of avoiding the re-invention of the wheel but at the same time relating the plan to the uniqueness of the town. The other plans include those of Brancaster, South Wootton, West Winch & North Runcton in West Norfolk; Langham and Uppingham in Rutland; St Ives in Cornwall; Exminster and Newton Abbot in Devon and East Preston in West Sussex Background – The Localism Act 2. In November 2011, the Localism Act was introduced with the aim of devolving more decision making powers from central government and providing: New freedoms and flexibilities for local government; New rights and powers for communities and individuals; Reform to make the planning system more democratic and more effective; Reform to ensure that decisions about housing and infrastructure are taken locally. 3. Through the development of a Neighbourhood Plan (NP), a community will now be able to propose the direction and degree of its own future development. 4. The Localism Act of 2011 introduced Neighbourhood Planning into the hierarchy of spatial planning in England. Once a Neighbourhood Plan has been accepted, it becomes a legal document and then sits alongside the Core Strategy (CS) and the Site Allocations and Development Management Policies Document (SADMP) and the County Minerals and Waste Plans. It informs all future planning decisions that the local planning authority makes about that particular community. 5. The HNDP describes a vision for the future of the town, which has been established through engagement with local residents and extensive consultation throughout the area. -

BRANCASTER 4.5 Miles / 7.25 Km

BRANCASTER 4.5 miles / 7.25 km 1 Defibrillator (AED) map location. Business location. 1 Route link. Route. TO BRANCASTER STAITHE Start point. Bus Stop Parking Church with toilet facilities WC WC 4 3 Point of heritage interest 2 Brancaster Beach Kiosk 1 Titchwell Manor 2 Briarfields Hotel 3 The Ship Hotel 4 Peddars Way & Norfolk Coast Path Business open times may vary. Please check with venue if you look to use their facilities & services. © Crown copyright and database rights 2019 Ordnance Survey 100019340 Modern Brancaster is a sleepy coastal village, albeit one with a Getting Started vibrant sailing scene. This circular walk offers a rich and varied The route’s starting point is on Mill Road opposite St. Mary’s past for the heritage explorer to delve into. Why not finish the Church, Brancaster (TF771438). walk at one of the local pubs, which have a history all of their own? Getting There There are bus stops near the route’s starting point served by When the numerous ports of north-west Norfolk’s coast were still busy with Lynx Coastliner service 36. trading ships, smuggling and piracy were also commonplace. Shipwrecks Limited car parking along A149 Main Road. Parking at provided coastal communities with unexpected, and often irresistible, Brancaster Beach Car Park, Broad Lane, PE31 8AX. Car parking opportunities to obtain valuable goods. fees may apply. Please check Brancaster tide times: high tides can flood the road leading to the car park. In September 1833 such an opportunity arose at Brancaster. The packet ship Earl of Wemyss, en-route from London to Edinburgh, became stranded on a sandbank during a storm. -

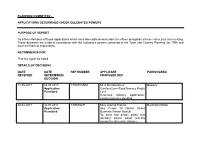

Delegated List

PLANNING COMMITTEE - APPLICATIONS DETERMINED UNDER DELEGATED POWERS PURPOSE OF REPORT To inform Members of those applications which have been determined under the officer delegation scheme since your last meeting. These decisions are made in accordance with the Authority’s powers contained in the Town and Country Planning Act 1990 and have no financial implications. RECOMMENDATION That the report be noted. DETAILS OF DECISIONS DATE DATE REF NUMBER APPLICANT PARISH/AREA RECEIVED DETERMINED/ PROPOSED DEV DECISION 11.05.2017 04.07.2017 17/00918/RM Mr & Mrs Blackmur Bawsey Application Conifers Lynn Road Bawsey King's Permitted Lynn Reserved Matters Application: construction of a dwelling 24.04.2017 12.07.2017 17/00802/F Miss Joanna Francis Burnham Norton Application Sea Peeps 19 Norton Street Permitted Burnham Norton Norfolk To erect two timber gates and ancillary picket panel fencing across the driveway entrance 12.04.2017 17.07.2017 17/00734/F Mr J Graham Burnham Overy Application The Images Wells Road Burnham Permitted Overy Town King's Lynn Construction of bedroom 22.02.2017 30.06.2017 17/00349/F Mr And Mrs J Smith Brancaster Application Carpenters Cottage Main Road Permitted Brancaster Staithe Norfolk Use of Holiday accommodation building as an unrestricted C3 dwellinghouse, including two storey and single storey extensions to rear and erection of detached outbuilding 05.04.2017 07.07.2017 17/00698/F Mr & Mrs G Anson Brancaster Application Brent Marsh Main Road Permitted Brancaster Staithe King's Lynn Demolition of existing house and -

GUN HILL from the Website Norfolk for the Book Discover Butterflies in Britain © D E Newland

GUN HILL from www.discoverbutterflies.com the website Norfolk for the book Discover Butterflies in Britain © D E Newland View from the summit of Gun Hill, looking north-east Gun Hill is a high sand dune A wide, sandy beach runs all TARGET SPECIES about a mile and a half from the way from Hunstanton to Dark Green Fritillaries, Burnham Overy Staithe on the Morston. Its mix of high sand Graylings, Brown Argus, North Norfolk Coast. It is dunes, low mud flats and tidal Small Heath and other accessible only by walking estuaries are part of the commoner species. from the Overy Staithe or Norfolk Coast AONB. Gun from a nearby informal car Hill is near Burnham Overy park on the A149 coast road. Staithe and within the Holkham NNR. This is owned by Lord Leicester’s Holkham Estate and managed in cooperation with Natural England. To reach Gun Hill, you have to walk for about half-an-hour, either from Burnham Overy Staithe or from informal roadside parking about ½ mile east of the Overy Staithe, on the A149 coast road. From the roadside lay-by, you walk for about ¾ mile through the Overy Marshes and then go up onto the sea wall. Here you join the Norfolk Coast Path from Burnham Overy Staithe to Wells-next-the-Sea. This is the footpath that you would be on if you started from Overy Staithe. It is a good, hard-surfaced path for about another ¾ mile, ending in a boardwalk as it approaches the sandy beach. Now the Coast Path bears right across the sands, but you bear left for Gun Hill. -

June 2019 Tour Report Norfolk in Early Summer with Nick Acheson

Tour Report UK – Norfolk in Early Spring with Nick Acheson 10 – 14 June 2019 Norfolk hawker dragonfly Stone curlew Bittern Marsh harrier Compiled by Nick Acheson 01962 302086 [email protected] www.wildlifeworldwide.com Tour Leader: Nick Acheson Day 1: Monday 10 June 2019 Months in advance, when planning tours to see swallowtail butterflies, dragonflies, wildflowers and summer birds in June, you don’t give a great deal of thought to a wild storm hitting — bringing wind, heavy rain and floods — and sticking around for a whole week. But such a storm hit today as you all reached Norfolk for the start of your tour. We met in the early afternoon at Knights Hill Hotel and, despite the rain, decided to head for RSPB Titchwell Marsh. Here we did manage to see a number of very nice birds, including many avocets and Mediterranean gulls, plenty of gadwall, teal and shoveler, a female marsh harrier, a ringed plover, a Sandwich tern, a fleeting bearded tit and a flyover spoonbill. However probably the most striking aspect of the afternoon was the relentless rain, which soaked us through whenever we were foolhardy enough to step outside a hide. Day 2: Tuesday 11 June 2019 In our original plan we should have headed to the Brecks today, but we decided instead — given the forecast of heavy rain all day — to drive along the North Norfolk coast, in the knowledge that at Norfolk Wildlife Trust Cley Marshes we could at least shelter in the hides. When we reached Cley, it was indeed raining very hard so we sped to Bishop’s Hide, the closest of all the hides. -

North Norfolk Coastal Landscape

What is the landscape like? Geomorphic processes on the landscape Underlying chalk with some flint deposits known Blakeney and Wells-next-to-Sea were flooded in January 2013 by a coastal storm surge. The low lying as drift from the Ice Age land makes them vulnerable. Glacial deposits of weak boulder clay is easily Sea level rises are leading to Stiffkey salt marsh to build making a natural sea defence eroded Coastal flooding from storm surges or high tides can cause sand dunes areas to disappear over night, Low lying coastline, the boundary between land such as at Wells-next-to-Sea in January 2013 and sea is not clear, with spits and salt marshes formed North Norfolk Wide, sandy beach backed by sand dunes at Holkham- shallow seabed so the tide goes out a Coastal long way allowing sand to dry out and be blown onshore Landscape Low cliffs at Hunstanton, Sheringham and Cromer- Why protect the coastline? harder chalk outcrops protrude from the land Spit at Blakeney point- area of deposition Entire village including Shipden and Keswick have been completely lost to the sea in the last century Salt marsh at Stiffkey- permanent feature Happisburgh is currently disappearing due to cliff retreat. People have lost their homes and are still Human Sea Defences battling to receive compensation for their losses. Sea Palling has been protected by a sea wall which has reduced transportation and created a wide Rip-rap barriers at Sheringham- large rocks placed in beach which provides a natural sea defence front of cliffs to dissipate wave -

Review of Seabird Demographic Rates and Density Dependence

JNCC Report No: 552 Review of Seabird Demographic Rates and Density Dependence Catharine Horswill1 & Robert A. Robinson1 February 2015 © JNCC, Peterborough 2015 1British Trust for Ornithology ISSN 0963 8901 For further information please contact: Joint Nature Conservation Committee Monkstone House City Road Peterborough PE1 1JY http://jncc.defra.gov.uk This report should be cited as: Horswill, C. & Robinson R. A. 2015. Review of seabird demographic rates and density dependence. JNCC Report No. 552. Joint Nature Conservation Committee, Peterborough. Review of Seabird Demographic Rates and Density Dependence Summary Constructing realistic population models is the first step towards reliably assessing how infrastructure developments, such as offshore wind farms, impact the population trends of different species. The construction of these models requires the individual demographic processes that influence the size of a population to be well understood. However, it is currently unclear how many UK seabird species have sufficient data to support the development of species-specific models. Density-dependent regulation of demographic rates has been documented in a number of different seabird species. However, the majority of the population models used to assess the potential impacts of wind farms do not consider it. Models that incorporate such effects are more complex, and there is also a lack of clear expectation as to what form such regulation might take. We surveyed the published literature in order to collate available estimates of seabird and sea duck demographic rates. Where sufficient data could not be gathered using UK examples, data from colonies outside of the UK or proxy species are presented. We assessed each estimate’s quality and representativeness. -

Norfolk Coast Partnership Member Organisations

CELEB 3 RAT 01 IN -2 G 4 2 9 0 9 Y 1 E A N R A S I O D R Norfolk Coast F A T U 20 H G YEARS E T N S O A R O F C O L GUARDIANK FREE guide to an area of outstanding natural beauty 2013 GET AROUND Discover and enjoy Coasthopper offers, competitions and walks CONNECT Help NWT appeal to join marshes ENJOY Events, Recipes, Art MARINE MARVELS SEALIFE SPECIAL 2 A SPECIAL PLACE NORFOLK COAST GUARDIAN 2013 NORFOLKNOR COAST THE NORFOLK COAST PPARTNERSART PARTNERSHIP NaturalNat England South Wing at Fakenham Fire Station, NorfolkNo County Council Norwich Road, Fakenham, Norfolk NR21 8BB T: 01328 850530 NoNorth Norfolk District Council E: offi[email protected] BoroughBorou Council of King’s Lynn W: www.norfolkcoastaonb.org.uk & West Norfolk Manager: Tim Venes Great Yarmouth Borough Council Policy and partnership officer: Estelle Hook Broads Authority Communications officer: Lucy Galvin Environment Agency Community and external funding English Heritage officers: Kate Dougan & Grant Rundle Business support assistant: Steve Tutt Norfolk Wildlife Trust Funding Partners National Trust DEFRA; Norfolk County Council; RSPB North Norfolk District Council; Country Land & Business Association Borough Council of King’s Lynn & West Norfolk National Farmers Union and Great Yarmouth Borough Council Community Representatives AONB Common Rights Holders The Norfolk Coast Guardian is published by Countrywide Publications on behalf of the Norfolk Wells Harbour Commissioners Coast Partnership. Editor: Lucy Galvin. Designed and produced by: Countrywide Publications The Wash and North Norfolk Coast T: 01502 725870. Printed by Iliffe Print on sustainable newsprint.