The Independent Sharia Panel of Lagos State

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The World Bank Implementation Status & Results

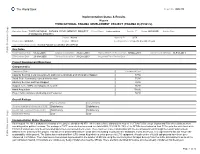

The World Bank Report No: ISR4370 Implementation Status & Results Nigeria THIRD NATIONAL FADAMA DEVELOPMENT PROJECT (FADAMA III) (P096572) Operation Name: THIRD NATIONAL FADAMA DEVELOPMENT PROJECT Project Stage: Implementation Seq.No: 7 Status: ARCHIVED Archive Date: (FADAMA III) (P096572) Country: Nigeria Approval FY: 2009 Product Line:IBRD/IDA Region: AFRICA Lending Instrument: Specific Investment Loan Implementing Agency(ies): National Fadama Coordination Office(NFCO) Key Dates Public Disclosure Copy Board Approval Date 01-Jul-2008 Original Closing Date 31-Dec-2013 Planned Mid Term Review Date 07-Nov-2011 Last Archived ISR Date 11-Feb-2011 Effectiveness Date 23-Mar-2009 Revised Closing Date 31-Dec-2013 Actual Mid Term Review Date Project Development Objectives Component(s) Component Name Component Cost Capacity Building, Local Government, and Communications and Information Support 87.50 Small-Scale Community-owned Infrastructure 75.00 Advisory Services and Input Support 39.50 Support to the ADPs and Adaptive Research 36.50 Asset Acquisition 150.00 Project Administration, Monitoring and Evaluation 58.80 Overall Ratings Previous Rating Current Rating Progress towards achievement of PDO Satisfactory Satisfactory Overall Implementation Progress (IP) Satisfactory Satisfactory Overall Risk Rating Low Low Implementation Status Overview As at August 19, 2011, disbursement status of the project stands at 46.87%. All the states have disbursed to most of the FCAs/FUGs except Jigawa and Edo where disbursement was delayed for political reasons. The savings in FUEF accounts has increased to a total ofN66,133,814.76. 75% of the SFCOs have federated their FCAs up to the state level while FCAs in 8 states have only been federated up to the Local Government levels. -

Violence in Nigeria's North West

Violence in Nigeria’s North West: Rolling Back the Mayhem Africa Report N°288 | 18 May 2020 Headquarters International Crisis Group Avenue Louise 235 • 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 • Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Preventing War. Shaping Peace. Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. Community Conflicts, Criminal Gangs and Jihadists ...................................................... 5 A. Farmers and Vigilantes versus Herders and Bandits ................................................ 6 B. Criminal Violence ...................................................................................................... 9 C. Jihadist Violence ........................................................................................................ 11 III. Effects of Violence ............................................................................................................ 15 A. Humanitarian and Social Impact .............................................................................. 15 B. Economic Impact ....................................................................................................... 16 C. Impact on Overall National Security ......................................................................... 17 IV. ISWAP, the North West and -

Isbn: 978-978-57350-2-4

ASSESSMENT AND REPAIR OF SOLAR STREETLIGHTS IN TOWNSHIP AND RURAL COMMUNITIES (Kwara, Kogi, Osun, Oyo, Nassarawa and Ekiti States) A. S. OLADEJI B. F. SULE A. BALOGUN I. T. ADEDAYO B. N. LAWAL TECHNICAL REPORT NO. 11 ISBN: 978-978-57350-2-4 NATIONAL CENTRE FOR HYDROPOWER RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT ENERGY COMMISSION OF NIGERIA UNIVERSITY OF ILORIN, ILORIN, NIGERIA DECEMBER, 2013 i TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents ii List of Figures iii List of Table iii 1.0 Introduction 2 1.1Background 2 1.2Objectives 4 2. 0Assessment of ECN 2008/2009 Rural Solar Streetlight Projects 5 2.1 Results of 2012 Re-assessment Exercise 5 2.1.1 Nasarawa State 5 2.1.1.1 Keffi 5 2.1.2 Kogi State 5 2.1.2.1 Banda 5 2.1.2.2 Kotonkarfi 5 2.1.2.3 Anyigba 5 2.1.2.4 Dekina 6 2.1.2.5 Egume 6 2.1.2.6 Acharu/Ogbogodo/Itama/Elubi 6 2.1.2.7 Abejukolo-Ife/Iyale/Oganenigu 6 2.1.2.8 Inye/Ofuigo/Enabo 6 2.1.2.9 Ankpa 6 2.1.2.10 Okenne 7 2.1.2.11 Ogaminana/Ihima 7 2.1.2.12 Kabba 7 2.1.2.13 Isanlu/Egbe 7 2.1.2.14 Okpatala-Ife / Dirisu / Obakume 7 2.1.2.15 Okpo / Imane 7 2.1.2.16 Gboloko / Odugbo / Mazum 8 2.1.2.17 Onyedega / Unale / Odeke 8 2.1.2.18 Ugwalawo /FGC / Umomi 8 2.1.2.19 Anpaya 8 2.1.2.20 Baugi 8 2.1.2.21 Mabenyi-Imane 9 ii 2.1.3 Oyo State 9 2.1.3.1 Gambari 9 2.1.3.2 Ajase 9 2.1.4 Kwara State 9 2.1.4.1Alaropo 9 2.1.5 Ekiti State 9 2.1.5.1 Iludun-Ekiti 9 2.1.5.2 Emure-Ekiti 9 2.1.5.3 Imesi-Ekiti 10 2.1.6 Osun State 10 2.1.6.1 Ile-Ife 10 2.1.6.3 Oke Obada 10 2.1.6.4 Ijebu-Jesa / Ere-Jesa 11 2.2 Summary Report of 2012 Re-Assessment Exercise, Recommendations and Cost for the Repair 11 2.3 Results of 2013 Re-assessment Exercise 27 2.2.1 Results of the Re-assessment Exercise 27 2.3.1.1 Results of Reassessment Exercise at Emir‟s Palace Ilorin, Kwara State 27 2.3.1.2 Results of Re-assessment Exercise at Gambari, Ogbomoso 28 2.3.1.3 Results of Re-assessment Exercise at Inisha 1&2, Osun State 30 3.0 Repairs Works 32 3.1 Introduction 32 3.2 Gambari, Surulere, Local Government, Ogbomoso 33 3.3 Inisha 2, Osun State 34 4. -

About the Contributors

ABOUT THE CONTRIBUTORS EDITORS MARINGE, Felix is Head of Research at the School of Education and Assistant Dean for Internationalization and Partnerships in the Faculty of Humanities, University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa. With Dr Emmanuel Ojo, he was host organizer of the Higher Education Research and Policy Network (HERPNET) 10th Regional Higher Education Conference on Sustainable Transformation and Higher Education held in South Africa in September 2015. Felix has the unique experience of working in higher education in three different countries, Zimbabwe; the United Kingdom and in South Africa. Over a thirty year period, Felix has published 60 articles in scholarly journals, written and co-edited 4 books, has 15 chapters in edited books and contributed to national and international research reports. Felix is a full professor of higher education at the School of Education, University of the Witwatersrand (WSoE) specialising in research around leadership, internationalisation and globalisation in higher education. OJO, Emmanuel is lecturer at the School of Education, University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa. He is actively involved in higher education research. His recent publication is a co-authored book chapter focusing on young faculty in South African higher education, titled, Challenges and Opportunities for New Faculty in South African Higher Education Young Faculty in the Twenty-First Century: International Perspectives (pp. 253-283) published by the State University of New York Press (SUNY). He is on the editorial board of two international journals: Journal of Higher Education in Africa (JHEA), a CODESRIA publication and Journal of Human Behaviour in the Social Environment, a Taylor & Francis publication. -

An Evaluation of the Implementation of Early Childhood Education Curriculum in Osun State

Journal of Education and Practice www.iiste.org ISSN 2222-1735 (Paper) ISSN 2222-288X (Online) Vol.6, No.4, 2015 An Evaluation of the Implementation of Early Childhood Education Curriculum in Osun State Okewole, Johnson Oludele Institute of Education,Obafemi Awolowo University,Ile-Ife, Osun State, Nigeria E-mail: [email protected] Iluezi-Ogbedu Veronica Abuovbo Department of Arts and Social Sciences,University of Lagos, Nigeria E-mail: [email protected] Osinowo Olufunke Abosede Department of Arts and Social Sciences,University of Lagos, Nigeria E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Early Childhood Education as a subject in primary schools in Nigeria was first noticed among the private primary schools in the 80’s while the public primary schools did not incorporate it in their curriculum in Nigeria. Of recent, some state governments in Nigeria have just adopted and organized early childhood education unit into their primary schools. As a result of this new development, the Nigerian Educational Research and Development Council (NERDC) developed a National Curriculum for E. C. E. which both public and private schools use to achieve the stated objectives of E.C.E. as contained in the National Policy on Education (2004) in Nigeria. It is based on this that this study carried out an evaluation of the implementation of the National Curriculum as prepared by NERDC by the primary schools in Osun State, Nigeria, vis a vis the quality of personnel on ground, the adequacy or otherwise of the teaching and learning facilities, comparison of the expected curriculum and the observed curriculum, and the constraints to its implementation. -

Jordan and the World Trading System: a Case Study for Arab Countries Bashar Hikmet Malkawi the American University Washington College of Law

American University Washington College of Law Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law SJD Dissertation Abstracts Student Works 1-1-2006 Jordan and the World Trading System: A Case Study for Arab Countries Bashar Hikmet Malkawi The American University Washington College of Law Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/stu_sjd_abstracts Part of the Economics Commons, and the Law Commons Recommended Citation Malkawi B. Jordan and the World Trading System: A Case Study for Arab Countries [S.J.D. dissertation]. United States -- District of Columbia: The American University; 2006. Available from: Dissertations & Theses @ American University - WRLC. Accessed [date], Publication Number: AAT 3351149. [AMA] This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in SJD Dissertation Abstracts by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JORDAN AND THE WORLD TRADING SYSTEM A CASE STUDY FOR ARAB COUNTRIES By Bashar Hikmet Malkawi Submitted to the Faculty of the Washington College of Law of American University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Juric] Dean of the Washington College of Law Date / 2005 American University 2 AMERICAN UNIVERSITY LIBRARY UMI Number: 3351149 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. -

AKWA, IDARA MERCY 53, Otunba Akin Joaquim Street, Ago Palace Way, Okota, Lagos State

AKWA, IDARA MERCY 53, Otunba Akin Joaquim street, Ago Palace Way, Okota, Lagos State. Email: [email protected] +2347067572392 OBJECTIVE: To garner relevant knowledge and skills while executing groundbreaking scholarly research work in the related fields of Food Science & Technology and Nutrition with a view to providing sustainable solutions to health and nutrition problems, locally and globally. PERSONAL DETAILS: Date of birth: 29th of September, 1997 Gender: Female Nationality: Nigerian SCHOOLS ATTENDED WITHDATE: Bowen University, Iwo, Osun State. 2012-2017 Baptist Model High School, Ijegun, Ikotun, Lagos. 2006-2012 QUALIFICATION WITH DATES: Bachelor of Science in Food Science and Technology, Second Class Honours (Upper division) 2017 West African Senior School Certificate (WASSCE) 2012 PROFESSIONAL QUALIFICATION WITH DATES: Health, Safety and Environment Management HSE 1, 2 and 3 2018 Project Management 2017 Microsoft Project 2017 WORK EXPERIENCE: Quality Control Superintendent at Seven-Up Bottling Company LTD 2019 till date Graduate Assistant at Department of Food Science and Nutrition, University of Ilorin 2017- 2018 Science Teacher at Mefami Int’l School 2017 Trainee Laboratory Analyst at NAFDAC (National Agency for Food and Drug Administration and Control) 2016 Trainee Laboratory Analyst at Champion Breweries, Akwa-Ibom 2014 VOLUNTARY ACTIVITIES: Recycling of waste PET Bottles into useable materials 2018 National Youth Service at National Youth Service Corps 2017-2018 Radio presenter on Health and Nutrition for -

Proquest Dissertations

NOTE TO USERS This reproduction is the best copy available. UMI* TEXTS OF TENSION, SPACES OF EMPOWERMENT: Migrant Muslims and the Limits of Shi'ite Legal Discourse Linda Darwish A Thesis in The Department of Religion Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada February 2009 © Linda Darwish, 2009 Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OttawaONK1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-63456-1 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-63456-1 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduce, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Plntemet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Metode Istidlal Dan Istishab (Formulasi Metodologi Ijtihad)

METODE ISTIDLAL DAN ISTISHAB (FORMULASI METODOLOGI IJTIHAD) Oleh: Umar Muhaimin Abstract Ra‟yu (logic) is an important aspect of ijtihad thus in ushul fiqh - a subject discussing the process of ijtihad – there are several method of finding the law based on logic of fuqaha (scholars), some of them are istishhab and istidlal (finding the sources). Those are two sides of a coin which are two inseparable methods of ijtihad. The source (dalil) is a material object while istidlal is a formal object. Generally, istidlal refers to finding sources either from Qur‟an, Sunna (Tradition), or al Maslahah (considerations of public interest) by means of muttafaq (settled methods) such as Qur‟an, Sunna (Tradition), Ijma‟ (consensus), Qiyas (analogy) or mukhtalaf (debatable methods) such as Mazhab ash-shahabi (fatwa of a companion), al-„urf (custom), Syar‟u Man Qablana (revealed laws before Islam), istihsan (equity), istishab (presumption of continuity) or sad al-dzariah (blocking the means). Al-Syatibi classified four mind sets of understanding nash (the Text) i.e. zahiriyah (textual), batiniyat (esoteric), maknawiyat (contextual) and combination between textual and contextual. Keyword: method, istidlal, istishab Abstrak Terkait dengan ijtihad, sisi ra‟yu (logika-logika yang benar) adalah hal yang tidak dapat dilepaskan darinya. Karena itu, dalam Ushul Fiqh –sebuah ilmu yang “mengatur” proses ijtihad- dikenal beberapa landasan penetapan hukum yang berlandaskan pada penggunaan kemampuan ra‟yu para fuqaha, salah satunya adalah istishhab. Selain itu ada yang bisa dipakai, yakni istidlal (penemuan dalil). Istishhab dan istidlal (penemuan dalil) merupakan dua metodologi ijtihad, yang bagaikan dua sisi mata uang. Artinya Metode Istidlal dan Istishab… ia merupakan dua metodologi ijtihad yang bertolak belakang, antara memilih Istishhab atau istidlal. -

An Evaluation of Peace Building Strategies in Southwestern Nigeria: Quantitative and Qualitative Examples

Journal of African Conflicts and eaceP Studies Volume 4 Issue 2 Article 7 January 2021 An Evaluation of Peace Building Strategies in Southwestern Nigeria: Quantitative and Qualitative Examples Kazeem Oyedele Lamidi Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/jacaps Part of the African Studies Commons, Development Studies Commons, Peace and Conflict Studies Commons, Policy Design, Analysis, and Evaluation Commons, Social Policy Commons, and the Social Work Commons Recommended Citation Lamidi, Kazeem Oyedele (2021) "An Evaluation of Peace Building Strategies in Southwestern Nigeria: Quantitative and Qualitative Examples," Journal of African Conflicts and eaceP Studies: Vol. 4: Iss. 2, . DOI: https://doi.org/10.5038/2325-484X.4.2.1143 Available at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/jacaps/vol4/iss2/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Access Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of African Conflicts and Peace Studies by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Lamidi: An Evaluation of Peace Building Strategies in Southwestern Nigeria: Quantitative and Qualitative Examples Introduction This paper took a departure from the World Summit in 2005 when Kofi Annan's proposal provided an insight into the creation of peacebuilding architecture. Arising from the plan of the proposal, strategies of peacebuilding were outlined to be useful before communal conflict as peace-making mechanisms and after conflict as peace-keeping techniques (Barnett, Kim, O.Donnell & Sitea, 2007). The crux of this paper is that, in spite of these peace enhancement strategies, most developing countries in Africa, Asia and Latin America are yet to enjoy long- term, sustained and durable peace (Okoro, 2014; & MacGinty, 2013). -

Fatwas for European Muslims: the Minority Fiqh Project and the Integration of Islam in Europe

FATWAS FOR EUROPEAN MUSLIMS: THE MINORITY FIQH PROJECT AND THE INTEGRATION OF ISLAM IN EUROPE Alexandre Vasconcelos Caeiro Fatwas for European Muslims: The Minority Fiqh Project and the Integration of Islam in Europe Fatwas voor Europese moslims: het project voor een fiqh voor minderheden en de integratie van de islam in Europa (met een samenvatting in het Nederlands) Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Universiteit Utrecht op gezag van de rector magnificus, prof.dr. G.J. van der Zwaan, ingevolge het besluit van het college voor promoties in het openbaar te verdedigen op vrijdag 1 juli 2011 des middags te 2.30 uur door Alexandre Vasconcelos Caeiro geboren op 22 februari 1978 te Lissabon, Portugal Promotor: Prof.dr. M. M. van Bruinessen This thesis was accomplished with financial support from the International Institute for the Study of Islam in the Modern World (ISIM) TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements v Transliteration vi Introduction 3 Part One: Muslim Theorizations Chapter 1: The Shifting Moral Universes of the Islamic Tradition of Ifta’ 13 Chapter 2: Theorizing Islam without the State: Debates on Minority Fiqh 45 Part Two: The European Council for Fatwa and Research Chapter 3: The Dynamics of Consultation 123 Chapter 4: Textual Relations of Authority 181 Chapter 5: Imagining an Islamic Counterpublic 209 Conclusion 233 Bibliography 241 Appendices 263 Samenvatting Curriculum Vitae Acknowledgements This work would not have been possible without a PhD fellowship from 2004- 2008 from the International Institute for the Study of Islam in the Modern World (ISIM) in Leiden, and the support - since 2009 - of the Erlangen Centre for Islam and Law in Europe (EZIRE) at the Friedrich-Alexander Universität in Nürnberg-Erlangen. -

A Comparative Analysis of Gender Participation in Educational Administration in Kwara and Osun State-Owned Tertiary Institutions

Journal of Alternative Perspective s in the Social Sciences ( 201 1) V ol 3 , No 2, 430 -445 A Comparative Analysis of Gender Participation in Educational Administration in Kwara and Osun State-Owned Tertiary Institutions Abdulkareem, A. Y, PhD; Saheed Oyeniran, PhD; Umaru, H.A, University of Ilorin (Ilorin, Nigeria). Yekeen, Adebayo Jimoh, Independent Researcher (Lagos, Nigeria). Abstract: The issue of disparity in access to educational opportunities has been a matter for discussion by a number of authors. It is desirable to find out the extent to which this disparity has affected gender participation in educational administration especially at the tertiary level. Information on the current state of affairs is necessary as some previous studies have recommended. The study is designed to compare gender participation in educational administration in State-owned tertiary institutions in two States namely Kwara and Osun. The population for the study comprised of two tertiary institutions in each of the states. A researcher designed instrument tagged “Gender Participation in Educational Administration Checklist” (GPEAC) was used to collect data from each of the Institutions. In other to ensure the validity of the instruments, it was presented to experts in the field of educational management for their criticism before it was administered. Five research questions were raised to guide the study. Stratified sampling technique was used to select two instructions from each of the States. The data collected were analyzed using descriptive statistics. The findings of the study revealed that females were highly discriminated against in holding high administrative posts; while females constitute about 30.5% of total staff strength in Osun State tertiary institutions and 29.5% in Kwara States respectively, female participation rates in these institutions were only 7% and 9% respectively.