New Wave Cinema”: a Reflection of the Sixth- Generation Auteurs and Their Productions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Other Books by Jonathan Rosenbaum

Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Other Books by Jonathan Rosenbaum Rivette: Texts and Interviews (editor, 1977) Orson Welles: A Critical View, by André Bazin (editor and translator, 1978) Moving Places: A Life in the Movies (1980) Film: The Front Line 1983 (1983) Midnight Movies (with J. Hoberman, 1983) Greed (1991) This Is Orson Welles, by Orson Welles and Peter Bogdanovich (editor, 1992) Placing Movies: The Practice of Film Criticism (1995) Movies as Politics (1997) Another Kind of Independence: Joe Dante and the Roger Corman Class of 1970 (coedited with Bill Krohn, 1999) Dead Man (2000) Movie Wars: How Hollywood and the Media Limit What Films We Can See (2000) Abbas Kiarostami (with Mehrmax Saeed-Vafa, 2003) Movie Mutations: The Changing Face of World Cinephilia (coedited with Adrian Martin, 2003) Essential Cinema: On the Necessity of Film Canons (2004) Discovering Orson Welles (2007) The Unquiet American: Trangressive Comedies from the U.S. (2009) Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Film Culture in Transition Jonathan Rosenbaum the university of chicago press | chicago and london Jonathan Rosenbaum wrote for many periodicals (including the Village Voice, Sight and Sound, Film Quarterly, and Film Comment) before becoming principal fi lm critic for the Chicago Reader in 1987. Since his retirement from that position in March 2008, he has maintained his own Web site and continued to write for both print and online publications. His many books include four major collections of essays: Placing Movies (California 1995), Movies as Politics (California 1997), Movie Wars (a cappella 2000), and Essential Cinema (Johns Hopkins 2004). The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2010 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. -

Download Press

VENICE FILM FESTIVAL - IN COMPETITION The World BY JIA ZHANG-KE China - 2004 - 138mins - 35mm - Color - 2:35 - Dolby Digital INTERNATIONAL PRESS CELLULOID DREAMS Richard Lormand the directors label In Venice 2 Rue Turgot, 75009 Paris, FRANCE T: + 39 347 651 0945 T: + 33 1 4970 0370 T: + 39 347 256 4143 F: + 33 1 4970 0371 [email protected] / www.filmpressplus.com [email protected] / www.celluloid-dreams.com Synopsis Tao is living out her dreams at World Park where visitors can see famous international monuments without ever leaving the Beijing suburbs. The pretty young dancer and her friends perform daily in lavish theme park shows among replicas of the Taj Mahal, the Eiffel Tower, St Mark's Square, Big Ben and the Pyramids. Tao and her boyfriend, security guard Taisheng, moved to the big city from the northern provinces a few years ago. Now their relationship has reached a crossroads. Taisheng becomes attracted to Qun, a fashion designer he meets on a trip back home. Tao's fellow dancers are on sentimental journeys of their own. Xiaowei questions her future with irresponsible boyfriend Niu. Meanwhile, Youyou uses romance to the advantage of her professional ambitions. Not everyone who comes to Beijing with high hopes can land a job where SMS games are accepted parts of daily life. Many, like manual laborer Erxiao, experience a much harsher reality. But, despite the fun and magic, even theme park microcosms are vulnerable to change. For Tao and those around her, there will be marriage and break-up, loyalty and infidelity, joy and tragedy. -

43E Festival International Du Film De La Rochelle Du 26 Juin Au 5 Juillet 2015 Le Puzzle Des Cinémas Du Monde

43e Festival International du Film de La Rochelle du 26 juin au 5 juillet 2015 LE PUZZLE DES CINÉMAS DU MONDE Une fois de plus nous revient l’impossible tâche de synthétiser une édition multiforme, tant par le nombre de films présentés que par les contextes dans lesquels ils ont été conçus. Nous ne pouvons nous résoudre à en sélectionner beaucoup moins, ce n’est pas faute d’essayer, et de toutes manières, un contexte économique plutôt inquiétant nous y contraint ; mais qu’une ou plusieurs pièces essentielles viennent à manquer au puzzle mental dont nous tentons, à l’année, de joindre les pièces irrégulières, et le Festival nous paraîtrait bancal. Finalement, ce qui rassemble tous ces films, qu’ils soient encore matériels ou virtuels (50/50), c’est nous, sélectionneuses au long cours. Nous souhaitons proposer aux spectateurs un panorama généreux de la chose filmique, cohérent, harmonieux, digne, sincère, quoique, la sincérité… Ambitieux aussi car nous aimons plus que tout les cinéastes qui prennent des risques et notre devise secrète pourrait bien être : mieux vaut un bon film raté qu’un mauvais film réussi. Et enfin, il nous plaît que les films se parlent, se rencontrent, s’éclairent les uns les autres et entrent en résonance dans l’esprit du festivalier. En 2015, nous avons procédé à un rééquilibrage géographique vers l’Asie, absente depuis plusieurs éditions de la programmation. Tout d’abord, avec le grand Hou Hsiao-hsien qui en est un digne représentant puisqu’il a tourné non seulement à Taïwan, son île natale mais aussi au Japon, à Hongkong et en Chine. -

Berkeley Art Museum·Pacific Film Archive W Inte R 2 0 18 – 19

WINTER 2018–19 BERKELEY ART MUSEUM · PACIFIC FILM ARCHIVE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PROGRAM GUIDE 100 YEARS OF COLLECTING JAPANESE ART ARTHUR JAFA MASAKO MIKI HANS HOFMANN FRITZ LANG & GERMAN EXPRESSIONISM INGMAR BERGMAN JIŘÍ TRNKA MIA HANSEN-LØVE JIA ZHANGKE JAMES IVORY JAPANESE FILM CLASSICS DOCUMENTARY VOICES OUT OF THE VAULT IN FOCUS: WRITING FOR CINEMA 1 / 2 / 3 / 4 CALENDAR DEC 9/SUN 21/FRI JAN 2:00 A Midsummer Night’s Dream 4:00 The Price of Everything P. 15 Introduction by Jan Pinkava 7:00 Fanny and Alexander BERGMAN P. 15 1/SAT TRNKA P. 12 3/THU 7:00 Full: Home Again—Tapestry 1:00 Making a Performance 1:15 Exhibition Highlights Tour P. 6 4:30 The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari P. 5 WORKSHOP P. 6 Reimagined Judith Rosenberg on piano 4–7 Five Tables of the Sea P. 4 5:30 The Good Soldier Švejk TRNKA P. 12 LANG & EXPRESSIONISM P. 16 22/SAT Free First Thursday: Galleries Free All Day 7:30 Persona BERGMAN P. 14 7:00 The Price of Everything P. 15 6:00 The Firemen’s Ball P. 29 5/SAT 2/SUN 12/WED 8:00 The Apartment P. 19 6:00 Future Landscapes WORKSHOP P. 6 12:30 Scenes from a 6:00 Arthur Jafa & Stephen Best 23/SUN Marriage BERGMAN P. 14 CONVERSATION P. 6 9/WED 2:00 Boom for Real: The Late Teenage 2:00 Guided Tour: Old Masters P. 6 7:00 Ugetsu JAPANESE CLASSICS P. 20 Years of Jean-Michel Basquiat P. 15 12:15 Exhibition Highlights Tour P. -

Mountains May Depart

presents MOUNTAINS MAY DEPART A film by JIA ZHANGKE 2015 Cannes Film Festival 2015 Toronto International Film Festival 2015 New York Film Festival China, Japan, France | 131 minutes | 2015 www.kinolorber.com Kino Lorber, Inc. 333 West 39th St. Suite 503 New York, NY 10018 (212) 629-6880 Publicity Contact: Rodrigo Brandao, [email protected] O: (212) 629-6880 Synopsis China, 1999. In Fenyang, childhood friends Liangzi, a coal miner, and Zhang, the owner of a gas station, are both in love with Tao, the town beauty. Tao eventually marries the wealthier Zhang and they have a son he names Dollar. 2014. Tao is divorced and her son emigrates to Australia with his business magnate father. Australia, 2025. 19-year-old Dollar no longer speaks Chinese and can barely communicate with his now bankrupt father. All that he remembers of his mother is her name…. Director’s Statement It’s because I’ve experienced my share of ups and downs in life that I wanted to make Mountains May Depart. This film spans the past, the present and the future, going from 1999 to 2014 and then to 2025. China’s economic development began to skyrocket in the 1990s. Living in this surreal economic environment has inevitably changed the ways that people deal with their emotions. The impulse behind this film is to examine the effect of putting financial considerations ahead of emotional relationships. If we imagine a point ten years into our future, how will we look back on what’s happening today? And how will we understand “freedom”? Buddhist thought sees four stages in the flow of life: birth, old age, sickness, and death. -

INEMA INTERNATIONAL Students, Faculty, Staff and the Community Are Invited • ADMISSION IS FREE • Donations Welcome 7:30 P.M

MURRAY STATE UNIVERSITY • Spring 2017 INEMA INTERNATIONAL Students, faculty, staff and the community are invited • ADMISSION IS FREE • Donations Welcome 7:30 p.m. Thursday, Friday and Saturday evenings • Curris Center Theater JAN. 26-27-28 • USA, 1992 MARCH 2-3-4 • USA, 2013 • SHAKESPEARE FESTIVAL THUNDERHEART WARM BODIES Dir. Michael Apted With Val Kilmer, Sam Shephard, Graham Greene. Dir. Jonathan Levine, In English and Sioux with English subtitles. Rated R, 119 mins. With Nicholas Hoult, Dave Franco, Teresa Palmer, Analeigh Tipton, John Malkovich Thunderheart is a thriller loosely based on the South Dakota Sioux Indian In English, Rated PG-13, 98 mins. uprising at Wounded Knee in 1973. An FBI man has to come to terms with his mixed blood heritage when sent to investigate a murder involving FBI A romantic horror-comedy film based on Isaac Marion's novel of the same agents and the American Indian Movement. Thunderheart dispenses with name. It is a retelling of the Romeo and Juliet love story set in an apocalyptic clichés of Indian culture while respectfully showing the traditions kept alive era. The film focuses on the development of the relationship between Julie, a on the reservation and exposing conditions on the reservation, all within the still-living woman, and "R", a zombie…A funny new twist on a classic love story, conventions of an entertaining and involving Hollywood murder mystery with WARM BODIES is a poignant tale about the power of human connection. R a message. (Axmaker, Sean. Turner Classic Movies 1992). The story is a timely exploration of civil rights issues and Julie must find a way to bridge the differences of each side to fight for a that serves as a forceful indictment of on-going injustice. -

MOUNTAINS MAY DEPART (SHAN HE GU REN) a Film by Jia Zhangke

MOUNTAINS MAY DEPART (SHAN HE GU REN) A film by Jia Zhangke In Competition Cannes Film Festival 2015 China/Japan/France 2015 / 126 minutes / Mandarin with English subtitles / cert. tbc Opens in cinemas Spring 2016 FOR ALL PRESS ENQUIRIES PLEASE CONTACT Sue Porter/Lizzie Frith – Porter Frith Ltd Tel: 020 7833 8444/E‐mail: [email protected] FOR ALL OTHER ENQUIRIES PLEASE CONTACT Robert Beeson – New Wave Films [email protected] New Wave Films 1 Lower John Street London W1F 9DT Tel: 020 3603 7577 www.newwavefilms.co.uk SYNOPSIS China, 1999. In Fenyang, childhood friends Liangzi, a coal miner, and Zhang, the owner of a gas station, are both in love with Tao, the town beauty. Tao eventually marries the wealthier Zhang and they have a son he names Dollar. 2014. Tao is divorced meets up with her son before he emigrates to Australia with his business magnate father. Australia, 2025. 19-year-old Dollar no longer speaks Chinese and can barely communicate with his now bankrupt father. All that he remembers of his mother is her name... DIRECTOR’S NOTE It’s because I’ve experienced my share of ups and downs in life that I wanted to make Mountains May Depart. This film spans the past, the present and the future, going from 1999 to 2014 and then to 2025. China’s economic development began to skyrocket in the 1990s. Living in this surreal economic environment has inevitably changed the ways that people deal with their emotions. The impulse behind this film is to examine the effect of putting financial considerations ahead of emotional relationships. -

Journal of Asian Studies Contemporary Chinese Cinema Special Edition

the iafor journal of asian studies Contemporary Chinese Cinema Special Edition Volume 2 – Issue 1 – Spring 2016 Editor: Seiko Yasumoto ISSN: 2187-6037 The IAFOR Journal of Asian Studies Volume 2 – Issue – I IAFOR Publications Executive Editor: Joseph Haldane The International Academic Forum The IAFOR Journal of Asian Studies Editor: Seiko Yasumoto, University of Sydney, Australia Associate Editor: Jason Bainbridge, Swinburne University, Australia Published by The International Academic Forum (IAFOR), Japan Executive Editor: Joseph Haldane Editorial Assistance: Rachel Dyer IAFOR Publications. Sakae 1-16-26-201, Naka-ward, Aichi, Japan 460-0008 Journal of Asian Studies Volume 2 – Issue 1 – Spring 2016 IAFOR Publications © Copyright 2016 ISSN: 2187-6037 Online: joas.iafor.org Cover image: Flickr Creative Commons/Guy Gorek The IAFOR Journal of Asian Studies Volume 2 – Issue I – Spring 2016 Edited by Seiko Yasumoto Table of Contents Notes on contributors 1 Welcome and Introduction 4 From Recording to Ritual: Weimar Villa and 24 City 10 Dr. Jinhee Choi Contested identities: exploring the cultural, historical and 25 political complexities of the ‘three Chinas’ Dr. Qiao Li & Prof. Ros Jennings Sounds, Swords and Forests: An Exploration into the Representations 41 of Music and Martial Arts in Contemporary Kung Fu Films Brent Keogh Sentimentalism in Under the Hawthorn Tree 53 Jing Meng Changes Manifest: Time, Memory, and a Changing Hong Kong 65 Emma Tipson The Taste of Ice Kacang: Xiaoqingxin Film as the Possible 74 Prospect of Taiwan Popular Cinema Panpan Yang Subtitling Chinese Humour: the English Version of A Woman, a 85 Gun and a Noodle Shop (2009) Yilei Yuan The IAFOR Journal of Asian Studies Volume 2 – Issue 1 – Spring 2016 Notes on Contributers Dr. -

The Dark Past Keeps Returning: Gender Themes in Neo-Noir by Heather Fireman

The Dark Past Keeps Returning: Gender Themes in Neo-Noir by Heather Fireman "Films are full of good things which really ought to be invented all over again. Again and again. Invented - not repeated. The good things should be found - found - in that precious spirit of the first time out, and images discovered - not referred to.... Sure, everything's been done.... Hell, everything had all been done when I started" -Orson Welles (Naremore 219). Film noir, an enigmatic and compelling mode, can and has been resurrected in many movies in recent years. So-called "neo-noirs" evoke the look, style, mood, or even just the feel of classic noir. Having sprung from a particular moment in history and resonating with the mentality of its audiences, noir should also be considered in terms of a context, which was vital to its ability to create meaning for its original audiences. We can never know exactly how those audiences viewed the noirs of the 1940s and 50s, but modern audiences obviously view them differently, in contexts "far removed from the ones for which they were originally intended" (Naremore 261). These films externalized fears and anxieties of American society of the time, generating a dark feeling or mood to accompany its visual style. But is a noir "feeling" historically bound? What does this mean for neo-noirs? Contemporary America has distinctive features that set it apart from the past. Even though neo-noir films may borrow generic conventions of classic noir, the "language" of noir is used to express anxieties belonging to modern times. -

The End of Japanese Cinema

THE END OF JAPANESE CINEMA TIMES ALEXANDER ZAHLTEN THE END OF JAPA NESE CINEMA studies of the weatherhead east asian institute, columbia university. The Studies of the Weatherhead East Asian Institute of Columbia University w ere inaugurated in 1962 to bring to a wider public the results of significant new research on modern and con temporary East Asia. alexander zahlten THE END OF JAPA NESE CINEMA Industrial Genres, National Times, and Media Ecologies Duke University Press · Durham and London · 2017 © 2017 DUKE UNIVERSITY PRESS All rights reserved Printed in the United States of Amer i ca on acid- free paper ∞ Text designed by Courtney Leigh Baker Typeset in Arno Pro and Din by Westchester Publishing Ser vices Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Zahlten, Alexander, [date] author. Title: The end of Japa nese cinema : industrial genres, national times, and media ecologies / Alexander Zahlten. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2017. | Series: Studies of the Weatherhead East Asian Institute, Columbia University | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Description based on print version rec ord and cip data provided by publisher; resource not viewed. Identifiers: lccn 2017012588 (print) lccn 2017015688 (ebook) isbn 9780822372462 (ebook) isbn 9780822369295 (hardcover : alk. paper) isbn 9780822369448 (pbk. : alk. paper) Subjects: lcsh: Motion pictures— Japan— History—20th century. | Mass media— Japan— History—20th century. Classification: lcc pn1993.5.j3 (ebook) | lcc pn1993.5.j3 Z34 2017 (print) -

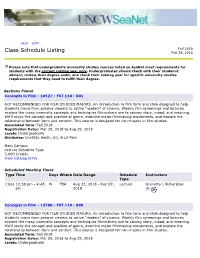

Class Schedule Listing Mar 28, 2018

HELP | EXIT Fall 2018 Class Schedule Listing Mar 28, 2018 Please note that undergraduate university studies courses listed on SeaNet meet requirements for students with the current catalog year only. Undergraduates should check with their academic advisor, review their degree audit, and check their catalog year for specific university studies requirements that they need to fulfill their degree. Sections Found Concepts in Film - 10527 - FST 110 - 001 NOT RECOMMENDED FOR FILM STUDIES MAJORS. An introduction to film form and style designed to help students move from passive viewers to active “readers” of cinema. Weekly film screenings and lectures explore the many cinematic concepts and techniques filmmakers use to convey story, mood, and meaning. We’ll study the concept and practice of genre, examine major filmmaking movements, and explore the relationship between form and content. This course is designed for non-majors in film studies. Associated Term: Fall 2018 Registration Dates: Mar 29, 2018 to Aug 29, 2018 Levels: Undergraduate Attributes: UnvStdy Aesth, Int, & Lit Pers Main Campus Lecture Schedule Type 3.000 Credits View Catalog Entry Scheduled Meeting Times Type Time Days Where Date Range Schedule Instructors Type Class 12:30 pm - 4:45 W TBA Aug 22, 2018 - Dec 07, Lecture Granetta L Richardson pm 2018 (P) Concepts in Film - 12780 - FST 110 - 800 NOT RECOMMENDED FOR FILM STUDIES MAJORS. An introduction to film form and style designed to help students move from passive viewers to active “readers” of cinema. Weekly film screenings and lectures explore the many cinematic concepts and techniques filmmakers use to convey story, mood, and meaning. -

Hartnett Dissertation

SSStttooonnnyyy BBBrrrooooookkk UUUnnniiivvveeerrrsssiiitttyyy The official electronic file of this thesis or dissertation is maintained by the University Libraries on behalf of The Graduate School at Stony Brook University. ©©© AAAllllll RRRiiiggghhhtttsss RRReeessseeerrrvvveeeddd bbbyyy AAAuuuttthhhooorrr... Recorded Objects: Time-Based Technologically Reproducible Art, 1954-1964 A Dissertation Presented by Gerald Hartnett to The Graduate School in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Art History and Criticism Stony Brook University August 2017 Stony Brook University 2017 Copyright by Gerald Hartnett 2017 Stony Brook University The Graduate School Gerald Hartnett We, the dissertation committee for the above candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy degree, hereby recommend acceptance of this dissertation. Andrew V. Uroskie – Dissertation Advisor Associate Professor, Department of Art Jacob Gaboury – Chairperson of Defense Assistant Professor, Department of Art Brooke Belisle – Third Reader Assistant Professor, Department of Art Noam M. Elcott, Outside Reader Associate Professor, Department of Art History, Columbia University This dissertation is accepted by the Graduate School Charles Taber Dean of the Graduate School ii Abstract of the Dissertation Recorded Objects: Time-Based, Technologically Reproducible Art, 1954-1964 by Gerald Hartnett Doctor of Philosophy in Art History and Criticism Stony Brook University 2017 Illuminating experimental, time-based, and technologically reproducible art objects produced between 1954 and 1964 to represent “the real,” this dissertation considers theories of mediation, ascertains vectors of influence between art and the cybernetic and computational sciences, and argues that the key practitioners responded to technological reproducibility in three ways. First of all, writers Guy Debord and William Burroughs reinvented appropriation art practice as a means of critiquing retrograde mass media entertainments and reportage.