Opioid Therapy and Its Side Effects: a Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

9780748668502 the Queen Of

The Queen of Sheba’s Gift Edinburgh Studies in Classical Islamic History and Culture Series Editor: Carole Hillenbrand A particular feature of medieval Islamic civilisation was its wide horizons. The Muslims fell heir not only to the Graeco-Roman world of the Mediterranean, but also to that of the ancient Near East, to the empires of Assyria, Babylon and the Persians; and beyond that, they were in frequent contact with India and China to the east and with black Africa to the south. This intellectual openness can be sensed in many interrelated fields of Muslim thought, and it impacted powerfully on trade and on the networks that made it possible. Books in this series reflect this openness and cover a wide range of topics, periods and geographical areas. Titles in the series include: Arabian Drugs in Early Medieval Defining Anthropomorphism Mediterranean Medicine Livnat Holtzman Zohar Amar and Efraim Lev Making Mongol History Towards a History of Libraries in Yemen Stefan Kamola Hassan Ansari and Sabine Schmidtke Lyrics of Life The Abbasid Caliphate of Cairo, 1261–1517 Fatemeh Keshavarz Mustafa Banister Art, Allegory and The Rise of Shiism In Iran, The Medieval Western Maghrib 1487–1565 Amira K. Bennison Chad Kia Christian Monastic Life in Early Islam The Administration of Justice in Bradley Bowman Medieval Egypt Keeping the Peace in Premodern Islam Yaacov Lev Malika Dekkiche The Queen of Sheba’s Gift Queens, Concubines and Eunuchs in Marcus Milwright Medieval Islam Ruling from a Red Canopy Taef El-Azhari Colin P. Mitchell Islamic Political -

Frankincense, Myrrh, and Balm of Gilead: Ancient Spices of Southern Arabia and Judea

1 Frankincense, Myrrh, and Balm of Gilead: Ancient Spices of Southern Arabia and Judea Shimshon Ben-Yehoshua Emeritus, Department of Postharvest Science Volcani Center Agricultural Research Organization Bet Dagan, 50250 Israel Carole Borowitz Bet Ramat Aviv Tel Aviv, 69027 Israel Lumır Ondrej Hanusˇ Institute of Drug Research School of Pharmacy Faculty of Medicine Hebrew University Ein Kerem, Jerusalem, 91120 Israel ABSTRACT Ancient cultures discovered and utilized the medicinal and therapeutic values of spices and incorporated the burning of incense as part of religious and social ceremonies. Among the most important ancient resinous spices were frankin- cense, derivedCOPYRIGHTED from Boswellia spp., myrrh, derived MATERIAL from Commiphoras spp., both from southern Arabia and the Horn of Africa, and balm of Gilead of Judea, derived from Commiphora gileadensis. The demand for these ancient spices was met by scarce and limited sources of supply. The incense trade and trade routes Horticultural Reviews, Volume 39, First Edition. Edited by Jules Janick. Ó 2012 Wiley-Blackwell. Published 2012 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 1 2 S. BEN-YEHOSHUA, C. BOROWITZ, AND L. O. HANUSˇ were developed to carry this precious cargo over long distances through many countries to the important foreign markets of Egypt, Mesopotamia, Persia, Greece, and Rome. The export of the frankincense and myrrh made Arabia extremely wealthy, so much so that Theophrastus, Strabo, and Pliny all referred to it as Felix (fortunate) Arabia. At present, this export hardly exists, and the spice trade has declined to around 1,500 tonnes, coming mainly from Somalia; both Yemen and Saudi Arabia import rather than export these frankincense and myrrh. -

Theriac in the Persian Traditional Medicine

235 Erciyes Med J 2020; 42(2): 235–8 • DOI: 10.14744/etd.2020.30049 HISTORY OF MEDICINE – OPEN ACCESS This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. Theriac in the Persian Traditional Medicine Ali Taghizadieh1 , Reza Mohammadinasab2 , Javad Ghazi-Sha’rbaf3 , Spyros N. Michaleas4 , Dimitris Vrachatis5 , Marianna Karamanou4 ABSTRACT Theriac is a term referring to medical compounds that were originally used by the Greeks from the first century A.D. to the Cite this article as: nineteenth century. The term derived from ancient Greek thēr (θήρ), “wild animal”. Nicander of Colophon (2nd century BC) Taghizadieh A, was the earliest known mention of Theriac in his work Alexipharmaka (Αλεξιφάρμακα), “drugs for protection”. During the era Mohammadinasab R, Ghazi-Sha’rbaf J, of King Mithridates VI of Pontus (132-63 BC), the universal antidote was known as mithridatium (μιθριδάτιο or mithridatum Michaleas SN, Vrachatis D, or mithridaticum) in acknowledgment of the compound’s supposed inventor or at least best-known beneficiary. It contained Karamanou M. Theriac in the around forty ingredients, such as opium, saffron, castor, myrrh, cinnamon and ginger. Theriac was not only used as an Persian Traditional Medicine. antidote from poisoning but also for various diseases, such as chronic cough, stomachache, asthma, chest pain, fever, colic, Erciyes Med J 2020; 42(2): 235–8. seizures, diarrhea, and retention of urine. The present study aims to collect and discuss the mentions of theriac in Persian medical texts. 1Tuberculosis and Lung Diseases Research Center, Keywords: History, traditional medicine, pharmacy, toxicology Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran 2Department of History of Medicine, Medical Philosophy INTRODUCTION and History Research Center, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Faculty of Since time immemorial, human beings have tried to discover or to create a universal antidote that could protect Traditional Medicine, against all poisons, whether they were derived from plants, animals, or minerals. -

Fifteenth Session

[Distributed to the Council and Official No. : C. 190. M. 90. 1930, III. the Members of the League.] Geneva, May 1930. LEAGUE OF NATIONS HEALTH COMMITTEE MINUTES O F T H E FIFTEENTH SESSION Held at Geneva from March 5th to 8th, 1930. Sertea o! Leag ations Publications T~: HEALTH 1930. III. 5. — 3 — CONTENTS Page List of Me m b e r s................................................................................................................................... 5 First Meeting, March 5th, 1930, at 4.30 p.m. : 437. Opening of the Session ........................................................................................... 7 438. Adoption of the Agenda of the Session................................................................... 7 439. Absence of Dr. J. Heng Liu from the Session........................................................ 7 440. Collaboration between the League of Nations and the Chinese Government as regards Health Matters : Statement by the Medical Director regarding the Mission to China................................................................................................... 7 441. Examination of the Chinese Government's Proposals for the Organisation of a National Quarantine Service : Appointment of a Sub-Commission................ 14 Second Meeting, March 6th, 1930, at 10 a.m. : 442. Collaboration between the League of Nations and the Chinese Government as regards Health Matters : General Discussion....................................................... 15 Third Meeting, March 7th, 1930, at 10.30 a.m. -

Cannabis Update • $48 Million Plant Research Center • Cinnamon And

HerbalGram 91 • August – October 2011 – October 2011 HerbalGram 91 • August Cannabis Update • $48 Million Plant Research Center • Cinnamon And Blood Sugar Lavender Oil And Anxiety • Reproducible Herb Quality • Medieval Arabic Manuscript • Bacopa Profile The Journal of the American Botanical Council Number 91 | August – October 2011 Cannabis Update • Cinnamon and Blood Sugar • Lavender Oil and Anxiety Herb Quality • Reproducible Manuscript • Medieval Profile • Cinnamon and Blood Sugar Lavender Arabic • Bacopa Update Cannabis www.herbalgram.org US/CAN $6.95 www.herbalgram.org 2011 www.herbalgram.orgHerbalGram 91 | 1 Herb Pharm’s Botanical Education Garden PRESERVING THE INTEGRITY OF NATURE'S CHEMISTRY The Art & Science of Herbal Extraction At Herb Pharm we continue to revere and follow the centuries-old, time-proven wisdom of traditional herbal medicine, but we also integrate that wisdom with the herbal sciences and technology of the 21st Century. We produce our herbal extracts in our new, FDA-audited, GMP- compliant herb processing facility which is located just two miles from our certified-organic herb farm. This assures prompt delivery of HPTLC chromatograph show- freshly-harvested herbs directly from the fields, or recently dried herbs ing biochemical consistency of 6 directly from the farm’s drying loft. Here we also receive other organic batches of St. John’s Wort extracts and wildcrafted herbs from various parts of the USA and world. In producing our herbal extracts we use precision scientific instru- ments to analyze each herb’s many chemical compounds. However, You’ll find Herb Pharm we do not focus entirely on the herb’s so-called “active compound(s)” at most health food stores and, instead, treat each herb and its chemical compounds as an integrated whole. -

A Shelflist of Islamic Medical Manuscripts at the National Library of Medicine

A Shelflist of Islamic Medical Manuscripts at the National Library of Medicine U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES Public Health Service | National Institutes of Health History of Medicine Division | National Library of Medicine Bethesda, Maryland 1996 Single copies of this booklet are available without charge by writing: Chief, History of Medicine Division National Library of Medicine 8600 Rockville Pike Bethesda, MD 20894 A Shelflist of Islamic Medical Manuscripts at the National Library of Medicine U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES Public Health Service | National Institutes of Health History of Medicine Division | National Library of Medicine Bethesda, Maryland 1996 Preface In 1994, to celebrate the 900th anniversary of the oldest Arabic medical manuscript in its collection, the History of Medicine Division of the National Library of Medicine mounted an exhibit entitled "Islamic Culture and the Medical Arts." Showcasing the library's rich holdings in this area, the exhibit was very well received -so much so that there has been a scholarly demand for the library to issue a catalogue of its holdings. This shelflist serves as an interim guide to the collection. It was made possible by the splendid work of Emilie Savage-Smith of Oxford University. Over the past few years, Dr. Savage-Smith has lent her time and her considerable expertise to the cataloguing of these manuscripts, examining every volume, providing much new information on authorship, contents, provenance, etc., superseding the earlier cataloguing by Francis E. Sommer, originally published in Dorothy M. Schullian and Francis E. Sommer, A Catalogue of Incunabula and Manuscripts in the Army Medical Library in 1950. -

Opiate Addiction Pathophysiology and Herbal Interventions

OPIATE ADDICTION PATHOPHYSIOLOGY AND HERBAL INTERVENTIONS DR JILLIAN STANSBURY FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: CONSULTANT TO RESTORATIVE FORMULATIONS CHASING THE DRAGON The are at least 4 million opiate addicts in the US alone. “Heroin is a multibillion dollar business At least 1.5 Million people supported by powerful interests, which undergo treatment for heroine requires a steady and secure addiction in the US each year. commodity flow. One of the “hidden” objectives of the war [in Afghanistan] was precisely to restore the CIA Opiate addiction is a leading sponsored drug trade to its historical cause of homelessness and a levels and exert direct control over the myriad of other social issues. drug routes.” Global Research, Center for Research on Globilization The Spoils of Opiate addiction may be a hidden War: Afghanistan’s Multibillion Dollar Heroin Trade Washington's agenda in Afghanistan. Hidden Agenda: Restore the Drug Trade Prof Michel Chossudovsky OPIATE ADDICTION Chasing the dragon, is the phenomenon where escalating quantities of drug are necessary to achieve the same level of satisfaction. There are around 30-40,000 opiate associated deaths per year in the US. Treatment for heroine and opiate addiction has the worst success rate – just 2-5% - of all addictive disorders. AN OPIATE EPIDEMIC IN THE US CDC reports that opiate sales, hospital MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. admissions, and opiate overdose deaths 2011 Nov 4;60(43):1487-92. Vital have tripled in the last 30 years and now signs: overdoses of prescription opioid pain relievers---United exceed motor vehicle deaths per year. States, 1999--2008.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). -

Theriac a SELECTED ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY of the HISTORY O'f THERIAC

The Pharmacist, May 1986 31 Theriac A SELECTED ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY OF THE HISTORY O'F THERIAC Imelda Serracino Inglott B.Phann., M.Sc. Origin honey were included :ts valuable stimulants ~r restoratives. As A. & G. Bouchartat state m Theriac,also treac•le in the English language, their Formulaire Magistral "this electuary in was a complex antidote and one of the most an corporates the most different ingredients one cient medicaments which was already in use in can think about: stimulants, tonics, astringents, the second century before Christ. antis.pasmotics and above all opium. Czl The French term for theriac is theriaque, the Theriaca Andromachus contains 65 odd ingre Latin theriaca, whilst in Greek it is known as dients. To these individual ingredients, Galen in theriake. Theriake was derived from theriakos his two books 'Antidotes and Theriake' ascribes (of wild or venomous beasts); hence theriac or certain qualities or powers. These fall up.der four theriake was an antidote which was primarily descriptions: heating, chiiling, drying and mois used against the bites of serpents, then against tening. For example frankincense is in the . se p:)isons in. general. cond order of heating and the first for drymg, The great antidote in Roman pharmacy was while opium is of the forth order of both heat Mithridatium, a pompous formule, which, it was ing and drying and is sharp and bitter. Crocus professed had been discovered among the papers is. slightly astringent, in the second ord.er of of Mithridates, King of Pontus, in Asia Minor heating and first in drying. A~ for a~tma•ls, from 114-63 B.C. -

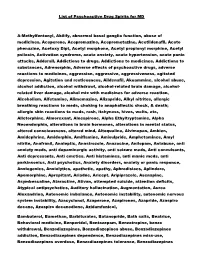

List of Psychoactive Drug Spirits for MD A-Methylfentanyl, Abilify

List of Psychoactive Drug Spirits for MD A-Methylfentanyl, Abilify, abnormal basal ganglia function, abuse of medicines, Aceperone, Acepromazine, Aceprometazine, Acetildenafil, Aceto phenazine, Acetoxy Dipt, Acetyl morphone, Acetyl propionyl morphine, Acetyl psilocin, Activation syndrome, acute anxiety, acute hypertension, acute panic attacks, Adderall, Addictions to drugs, Addictions to medicines, Addictions to substances, Adrenorphin, Adverse effects of psychoactive drugs, adverse reactions to medicines, aggression, aggressive, aggressiveness, agitated depression, Agitation and restlessness, Aildenafil, Akuammine, alcohol abuse, alcohol addiction, alcohol withdrawl, alcohol-related brain damage, alcohol- related liver damage, alcohol mix with medicines for adverse reaction, Alcoholism, Alfetamine, Alimemazine, Alizapride, Alkyl nitrites, allergic breathing reactions to meds, choking to anaphallectic shock, & death; allergic skin reactions to meds, rash, itchyness, hives, welts, etc, Alletorphine, Almorexant, Alnespirone, Alpha Ethyltryptamine, Alpha Neoendorphin, alterations in brain hormones, alterations in mental status, altered consciousness, altered mind, Altoqualine, Alvimopan, Ambien, Amidephrine, Amidorphin, Amiflamine, Amisulpride, Amphetamines, Amyl nitrite, Anafranil, Analeptic, Anastrozole, Anazocine, Anilopam, Antabuse, anti anxiety meds, anti dopaminergic activity, anti seizure meds, Anti convulsants, Anti depressants, Anti emetics, Anti histamines, anti manic meds, anti parkinsonics, Anti psychotics, Anxiety disorders, -

Download Full Book

Migraine Foxhall, Katherine Published by Johns Hopkins University Press Foxhall, Katherine. Migraine: A History. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2019. Project MUSE. doi:10.1353/book.66229. https://muse.jhu.edu/. For additional information about this book https://muse.jhu.edu/book/66229 [ Access provided at 24 Sep 2021 04:55 GMT with no institutional affiliation ] This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Migraine This page intentionally left blank Migraine A HISTORY ✷ ✷ ✷ Katherine Foxhall Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore This book was brought to publication with the generous assistance of the Wellcome Trust. © 2019 Johns Hopkins University Press This work is also available in an Open Access edition, which is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution–NonCommercial–NoDerivatives 4.0 International License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc -nd/4.0/. All rights reserved. Published 2019 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Johns Hopkins University Press 2715 North Charles Street Baltimore, Maryland 21218-4363 www.press.jhu.edu Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Foxhall, Katherine, author. Title: Migraine : a history / Katherine Foxhall. Description: Baltimore : Johns Hopkins University Press, 2019. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2018039557 | ISBN 9781421429489 (pbk. : alk. paper) | ISBN 1421429489 (pbk. : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781421429496 (electronic) | ISBN 1421429497 (electronic) | ISBN 9781421429502 (electronic open access) | ISBN 1421429500 (electronic open access) Subjects: | MESH: Migraine Disorders—history Classification: LCC RC392 | NLM WL 11.1 | DDC 616.8/4912—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018039557 A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. -

Medicinal Aspects of Opium As Described in Avicenna's

Pregledni ~lanak Acta med-hist Adriat 2013; 11(1);101-112 Review article UDK: 61(091):178.8 MEDICINAL ASPECTS OF OPIUM AS DESCRIBED IN AVICENNA’S CANON OF MEDICINE OPIJUM S MEDICINSKOG GLEDIŠTA KAKO JE PRIKAZAN U AVICENINU KANONU MEDICINE Mojtaba Heydari1,2, Mohammad Hashem Hashempur1,2, Arman Zargaran3,4 Summary Throughout history, opium has been used as a base for the opioid class of drugs used to suppress the central nervous system. Opium is a substance extracted from the opium poppy (Papaver somniferum L.). Its consumption and medicinal application date back to antiquity. In the me- dieval period, Avicenna, a famous Persian scholar (980-1037 AD) described poppy under the entry Afion of his medical encyclopedia Canon of Medicine. Various effects of opium con- sumption, both wanted and unwanted are discussed in the encyclopedia. The text mentions the effects of opioids such as analgesic, hypnotic, antitussive, gastrointestinal, cognitive, respiratory depression, neuromuscular disturbance, and sexual dysfunction. It also refers to its potential as a poison. Avicenna describes several methods of delivery and recommendations for doses of the drug. Most of opioid effects described by Avicenna have subsequently been confirmed by mod- ern research, and other references to opium use in medieval texts call for further investigation. This article highlights an important aspect of the medieval history of medicine. Key words: Opium, Avicenna, History of medicine, Persia, Canon of Medicine 1 Student Research Committee, Department of History of Medicine, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran. 2 The Essence of Persian Wisdom Institute and Department of Traditional Medicine, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran 3 Research Office for the History of Persian Medicine, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran 4 Department of Traditional Pharmacy, Faculty of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences Research Center, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran. -

(Theriac): an Important Formulation in Unani Medicine

The Journal of Phytopharmacology 2020; 9(6): 429-432 Online at: www.phytopharmajournal.com Review Article History and Traditional uses of Tiryaq (Theriac): An ISSN 2320-480X important formulation in Unani medicine JPHYTO 2020; 9(6): 429-432 November- December Mohd Aleem*, Md Imran Khan, Mohd Danish, Ajaz Ahmad Received: 10-10-2020 Accepted: 14-11-2020 ABSTRACT ©2020, All rights reserved doi: 10.31254/phyto.2020.9608 The history of Tiryaq is around 2000 years old and, since ancient times, has been regarded as a universal antidote. It was a complex compound consisting of many ingredients, originating as a cure for the bite of Mohd Aleem poisonous wild animals, mad dogs, or wild beasts. Tiryaq was not a usual antidote; it was not developed Department of Pharmacology, National Institute of Unani medicine, Bangalore- to cure or prevent a particular disease. It was a multi-medicine to protect against all poisons and treat 560091, India different conditions, such as chronic cough, stomach-ache, asthma, chest pain, fever, colic, seizures, diarrhoea, and urine retention. The belief that Tiryaq could protect individuals from poisons and various Md Imran Khan maladies persisted well into the modern era, only gradually being dispelled by the progress of Western Department of Pharmacology, National Institute of Unani medicine, Bangalore- medicine founded on scientific principles. Tiryaq was taken off most formularies, although now it survived 560091, India in India and a few European cities. Mohd Danish Department of Dermatology, National Keywords: Tiryaq; Theriac; Antidote; Mithridate; Andromachus; Unani medicine. Institute of Unani medicine, Bangalore- 560091, India Ajaz Ahmad 1.