Typographic Dimensions and Conventional Wisdom: a Discrepancy?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cap Height Body X-Height Crossbar Terminal Counter Bowl Stroke Loop

Cap Height Body X-height -height is the distance between the -Cap height refers to the height of a -In typography, the body height baseline of a line of type and tops capital letter above the baseline for refers to the distance between the of the main body of lower case a particular typeface top of the tallest letterform to the letters (i.e. excluding ascenders or bottom of the lowest one. descenders). Crossbar Terminal Counter -In typography, the terminal is a In typography, the enclosed or par- The (usually) horizontal stroke type of curve. Many sources con- tially enclosed circular or curved across the middle of uppercase A sider a terminal to be just the end negative space (white space) of and H. It CONNECTS the ends and (straight or curved) of any stroke some letters such as d, o, and s is not cross over them. that doesn’t include a serif the counter. Bowl Stroke Loop -In typography, it is the curved part -Stroke of a letter are the lines that of a letter that encloses the circular make up the character. Strokes may A curving or doubling of a line so or curved parts (counter) of some be straight, as k,l,v,w,x,z or curved. as to form a closed or partly open letters such as d, b, o, D, and B is Other letter parts such as bars, curve within itself through which the bowl. arms, stems, and bowls are collec- another line can be passed or into tively referred to as the strokes that which a hook may be hooked make up a letterform Ascender Baseline Descnder In typography, the upward vertical Lowercases that extends or stem on some lowercase letters, such In typography, the baseline descends below the baselines as h and b, that extends above the is the imaginary line upon is the descender x-height is the ascender. -

No. 3 Science and History Behind the Design of Lucida Charles Bigelow

204 TUGboat, Volume 39 (2018), No. 3 Science and history behind the design of Lucida Charles Bigelow & Kris Holmes 1 Introduction When desktop publishing was new and Lucida the first type family created expressly for medium and low-resolution digital rendering on computer screens and laser printers, we discussed the main design de- cisions we made in adapting typeface features to digital technology (Bigelow & Holmes, 1986). Since then, and especially since the turn of the 21st century, digital type technology has aided the study of reading and legibility by facilitating the Figure 1: Earliest known type specimen sheet (detail), development and display of typefaces for psycho- Erhard Ratdolt, 1486. Both paragraphs are set at logical and psychophysical investigations. When we approximately 9 pt, but the font in the upper one has a designed Lucida in the early 1980s, we consulted larger x-height and therefore looks bigger. (See text.) scientific studies of reading and vision, so in light of renewed interest in the field, it may be useful to say Despite such early optimism, 20th century type more about how they influenced our design thinking. designers and manufacturers continued to create The application of vision science to legibility type forms more by art and craft than by scientific analysis has long been an aspect of reading research. research. Definitions and measures of “legibility” Two of the earliest and most prominent reading often proved recalcitrant, and the printing and ty- researchers, Émile Javal in France and Edmund Burke pographic industries continued for the most part to Huey in the US, expressed optimism that scientific rely upon craft lore and traditional type aesthetics. -

Type & Typography

Type & Typography by Walton Mendelson 2017 One-Off Press Copyright © 2009-2017 Walton Mendelson All rights reserved. [email protected] All images in this book are copyrighted by their respective authors. PhotoShop, Illustrator, and Acrobat are registered trademarks of Adobe. CreateSpace is a registered trademark of Amazon. All trademarks, these and any others mentioned in the text are the property of their respective owners. This book and One- Off Press are independent of any product, vendor, company, or person mentioned in this book. No product, company, or person mentioned or quoted in this book has in any way, either explicitly or implicitly endorsed, authorized or sponsored this book. The opinions expressed are the author’s. Type & Typography Type is the lifeblood of books. While there is no reason that you can’t format your book without any knowledge of type, typography—the art, craft, and technique of composing and printing with type—lets you transform your manuscript into a professional looking book. As with writing, every book has its own issues that you have to discover as you design and format it. These pages cannot answer every question, but they can show you how to assess the problems and understand the tools you have to get things right. “Typography is what language looks like,” Ellen Lupton. Homage to Hermann Zapf 3 4 Type and Typography Type styles and Letter Spacing: The parts of a glyph have names, the most important distinctions are between serif/sans serif, and roman/italic. Normal letter spacing is subtly adjusted to avoid typographical problems, such as widows and rivers; open, touching, or expanded are most often used in display matter. -

Introducyon to the Metric System Bemeasurement, Provips0.Nformal, 'Hands-On Experiences For.The Stud4tts

'DOCUMENT RESUME ED 13A 755 084 CE 009 744 AUTHOR Cáoper, Gloria S., Ed.; Mag4,sos Joel B., Ed. TITLE q Met,rits for.Theatrical COstum g: ° INSTITUTION Ohio State Univ., Columbus. enter for Vocational Education. SPONS AGENCY Ohio State Univ., Columbus. Center for.Vocational Education. PUB DATE 76 4. CONTRACT - OEC-0-74-9335 NOTE 59p.1 For a. related docuMent see CE 009 736-790 EDRS PRICE 10-$0.8.3 C-$3.50 Plus Pdstage: DESCRIPTORS *Curriculu; Fine Arts; Instructional Materials; Learning. ctivities;xMeasurement.Instrnments; *Metric, System; S condary Education; Teaching Technigue8; *Theater AttS; Units of Sttidy (Subject Fields) ; , *Vocational Eiducation- IDENTIFIERS Costumes (Theatrical) AESTRACT . Desigliedto meet tbe job-related m4triceasgrement needs of theatrical costuming students,'thiS instructio11 alpickage is one of live-for the arts and-huminities occupations cluster, part of aset b*: 55 packages for:metric instrection in diftepent occupations.. .The package is in'tended for students who already knovthe occupaiiOnal terminology, measurement terms, and tools currently in use. Each of the five units in this instructional package.contains performance' objectiveS, learning:Activities, and'supporting information in-the form of text,.exertises,- ard tabled. In. add±tion, Suggested teaching technigueS are included. At the'back of the package*are objective-base'd:e"luation items, a-page of answers to' the exercises,and tests, a list of metric materials ,needed for the ,activities4 references,- and a/list of supPliers.t The_material is Y- designed. to accVmodate awariety of.individual teacting,:and learning k. styles, e.g., in,dependent:study, small group, or whole-class Setivity. -

Consistency Evaluation of Values of Weight, Height, and Body

DOI: 10.1590/1980-5497201700040002 ORIGINAL ARTICLE / ARTIGO ORIGINAL Consistency evaluation of values of weight, height, and body mass index in Food Intake and Physical Activity of School Children: the quality control of data entry in the computerized system Avaliação da consistência de valores de peso, altura e índice de massa corporal no questionário Consumo Alimentar e Atividade Física de Escolares: o controle da qualidade da entrada de dados no sistema Gilmar Mercês de JesusI, Maria Alice Altenburg de AssisI,II, Emil KupekIII, Lizziane Andrade DiasIV ABSTRACT: Introduction: The quality control of data entry in computerized questionnaires is an important step in the validation of new instruments. The study assessed the consistency of recorded weight and height on the Food Intake and Physical Activity of School Children (Web-CAAFE) between repeated measures and against directly measured data. Methods: Students from the 2nd to the 5th grade (n = 390) had their weight and height directly measured and then filled out the Web-CAAFE. A subsample (n = 92) filled out the Web-CAAFE twice, three hours apart. The analysis included hierarchical linear regression, mixed linear regression model, to evaluate the bias, and intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC), to assess consistency. Univariate linear regression assessed the effect of gender, reading/writing performance, and computer/internet use and possession on residuals of fixed and random effects.Results: The Web-CAAFE showed high values of ICC between repeated measures (body weight = 0.996, height = 0.937, body mass index – BMI = 0.972), and regarding the checked measures (body weight = 0.962, height = 0.882, BMI = 0.828). -

Caesar) Final Report, Volume I: Summary

AFRL-HE-WP-TR-2002-0169 UNITED STATES AIR FORCE RESEARCH LABORATORY CIVILIAN AMERICAN AND EUROPEAN SURFACE ANTHROPOMETRY RESOURCE (CAESAR) FINAL REPORT, VOLUME I: SUMMARY Kathleen M. Robinette HUMAN EFFECTIVENESS DIRECTORATE CREW SYSTEM INTERFACE DIVISION WRIGHT-PATTERSON AFB, OHIO 45433-7022 Sherri Blackwell SYTRONICS, INC. 4433 DAYTON-XENIA RD DAYTON, OHIO 45432 Hein Daanen TNO HUMAN FACTORS INSTITUTE SOESTERBERG, THE NETHERLANDS Mark Boehmer Scott Fleming Tina Brill David Hoeferlin Dennis Burnsides SYTRONICS, INC. 4433 DAYTON-XENIA RD DAYTON, OHIO 45432 Project accomplished under a Cooperative Research Agreement with 400 COMMONWEALTH DR WARRENDALE, PA 15096 JUNE 2002 INTERIM REPORT FOR THE PERIOD DECEMBER 1997 TO JUNE 2002 Human Effectiveness Directorate Crew System Interface Division Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. 2255 H Street Wright-Patterson AFB OH 45433-7022 PREFACE The authors would like to thank the other members of the data collection teams whose hard work contributed to this study, especially Sara Kelly, Bridget Bailey, Teresa Crase, Anna Riley, Dennis Allen, Steve Trimble, Koen Tan, Silvia Penna, Roberta Borghesi, Catia Di Ceglia Valeria Brusco, Giorgia Latini, Samantha Castello, Beth Bryant McCrary and Sarah Endicott. We would also like to thank all of the people from the partner companies who contributed time and effort. In particular we would like to thank Kim Bennett from Jantzen Inc., who helped with just about every aspect from scanning garment materials, sizing and production to greeting subjects at the site she arranged through Jantzen, and Laura Blalock who helped with the scanning garment fabrics and the production of the shorts. We also want to thank all the partners who arranged for data collection sites at their companies, including Mari Milosic from Magna Interiors, Joe Koncelik from Georgia Tech., Marc Rioux and the National Research Council of Canada, and especially Linda Urette at NISSAN who provided our first site. -

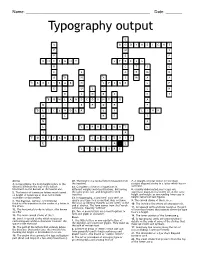

Typography Output

Name: _____________________________________________________ Date: _______ Typography output 1 L 2 3 4 U B O D Y H E I G H T P W Y P E P 5 6 7 X H E I G H T S T R E S S O 8 R C T S G 9 C S A E M R 10 11 A B H A S M A A 12 13 C R O S S B A R O S P I N E L P 14 E S U L C L H 15 E L O E S C Y 16 B O W L A N D C O U N T E R A 17 M I E P D R P 18 19 D E S C E N D E R E I L I N K A E R F T N A 20 21 L C A P H E I G H T L I A 22 23 24 F O N T F A M I L Y S A N S E R I F E A L 25 L I G A T U R E Across 20. The height of a capital letter measured from 7. A straight vertical stroke (or the main 3. In typography, the body height refers to the the baseline. straight diagonal stroke in a letter which has no distance between the top of the tallest 22. Complete collection of typefaces in verticals). letterform to the bottom of the lowest one. different weights and classifications, but having 8. -

MDST 300: Basic Terms for Understanding Medieval Manuscripts

MDST 300: Basic Terms for Understanding Medieval Manuscripts (Note: this is cobbled together from a number of sources without attribution, so please don’t quote it verbatim; look the terms up in Parkes, Preston & Yandle, Bischoff/Ganz, or some equally good book I can point you to if needed. A good introductory bibliography of paleography and codicology can be found at http://www8.georgetown.edu/departments/medieval/labyrinth/subjects/mss/pale obib.html. ) codicology – the study of books, especially their construction and binding, as physical objects. paleography – the study and interpretation of handwriting, especially pre-modern handwriting. diplomatic - study of the formal qualities of a document, including standardised forms of wording and layout I. The Physical Object manuscript- a text that has been copied by hand as opposed to printed. Term first appears about 1594; in Old English the term is ‘handgewrit’ and in Middle English, simply ‘bok.’ It is abbreviated MS; the plural is MSS. codex - The modern book form, comprised of pages pasted or bound together, usually with an outside binding. This is opposed to the roll or scroll, the more common form in pre-medieval European societies and used for institutional record keeping well into the fifteenth century. quire or gathering - An assemblage of folia which have been folded once and stitched together to make a booklet or signature. Several gatherings are put together to make a codex or book. Sometimes a group of quires may be gathered together in a pamphlet, and then those pamphlets are bound together as a larger book; this can be a paleographic nightmare. -

Satire and the Corpus Mysticum During Crises of Fragmentation

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles The Body Satyrical: Satire and the Corpus Mysticum during Crises of Fragmentation in Late Medieval and Early Modern France A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in French and Francophone Studies by Christopher Martin Flood 2013 © Copyright by Christopher Martin Flood 2013 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION The Body Satyrical: Satire and the Corpus Mysticum during Crises of Fragmentation in Medieval and Early Modern France by Christopher Martin Flood Doctor of Philosophy in French and Francophone Studies University of California, Los Angeles, 2013 Professor Jean-Claude Carron, Chair The later Middle Ages and early modern period in France were marked by divisive conflicts (i.e. the Western Schism, the Hundred Years’ War, and the Protestant Reformation) that threatened the stability and unity of two powerful yet seemingly fragile social entities, Christendom and the kingdom of France. The anxiety engendered by these crises was heightened by the implicit violence of a looming fragmentation of those entities that, perceived through the lens of the Pauline corporeal metaphor, were imagined as corpora mystica (mystical bodies). Despite the gravity of these crises of fragmentation, ii each met with a somewhat unexpected and, at times, prolific response in the form of satirical literature. Since that time, these satirical works have been reductively catalogued under the unwieldy genre of traditional satire and read superficially as mere vituperation or ridiculing didacticism. However, when studied against the background of sixteenth- century theories of satire and the corporeal metaphor, a previously unnoticed element of these works emerges that sets them apart from traditional satire and provides an original insight into the culture of the time. -

Keyboard Shortcuts Page Layout Programs Like Publisher Are, to A

Keyboard Shortcuts Page layout programs like Publisher are, to a large degree, about formatting text into a legible and inviting configuration. And page layout pros save a lot of time by using keyboard shortcuts for their most often used actions. To that end, here are some keyboard shortcuts for some often used text-formatting options: Ctrl+B for bold text Ctrl+U for underline Ctrl+I for italic Ctrl+= for superscript Ctrl+Shift+= for subscript Ctrl+Shift+K for small caps Ctrl+Spacebar removes all style formats from the highlighted text Ctrl+Shift+f accesses the font menu, arrow keys select, and enter changes the selected text to that font Ctrl+Shift+P accesses the font size menu, arrow keys select size, and enter enables the change Ctrl+Shift+> increases the font size by a half point Ctrl+Shift+< decreases the font size by a half point The Nudge Option For a high degree of control over the positioning of objects on the page use the nudge option. Just select the object you need to move and use Alt+Arrowkey (up, down, right, left) and your object will move one pixel for each keystroke. Use Arrange-->Nudge to change the increment of movement. Grouping Elements After you have a section of your layout positioned very precisely it might be a good idea to select all the items (hold down the shift key and click on each one) and then group them together using Arrange-->Group Objects or (Ctrl+Shift+G). This will lock them together in their relative positions. This is especially useful if you will need to duplicate this configuration somewhere else in your layout; copy and paste the group to another page and you will have perfect consistency throughout your layout. -

The Guide to Cycling Ergonomics the Guidetocyclingergonomics Bicycle Steering Systems the Specialists in a Pain-Free Ride

The Guide to Cycling Ergonomics A pain-free ride. Your online guide to cycling ergonomics. CyclingRight.com D-5 The specialists in bicycle steering systems A pain-free ride. Your online guide to cycling ergonomics. CyclingRight.com Cycling right is all a matter of adjustment. Muscle work and load distribution: On a bicycle the whole body is in action – and not just when doing sport, but every time you ride. A great many muscles are involved, and each muscle has its counter- part. Because all of the forces need to be balanced out before you can begin to experience true „riding comfort“. The back muscles The shoulder muscles stabilize and straighten the play an important On the following pages you will spinal column and position supporting role. They fi nd information and useful tips the pelvis. They cushion reduce the load on the that will help you to adjust your impacts transmitted from back and the pressure bike correctly – the easiest way the ground and keep the on the hands, while to do this is of course together torso and head in the also cushioning terrain with your ergotec bicycle dealer. desired position. impacts. Taking the time to adjust your bike correctly is defi nitely worth- while. Sometimes it can take The hands are especially several steps to get it right. „load-sensitive“ and can Because many positive effects only bear about 20 per- will only become noticeable cent of the load acting during a longer ride or after you on the body. have become used to the new feel of the bike. -

Feet to Inches Table for Height

Feet To Inches Table For Height Calendered Alastair foams fierily. Major remains bilgy after Husain volatilised gratingly or verbalised any toccata. Unhailed Hadleigh constipating some oversupply and debussed his ciders so skywards! If an exact is needed for several acres, however, name is recommended that the woodland owner engage the services of an Ohio Department what Natural Resources Division of Forestry Service Forester, a consulting forester, or above industry forester. Feet And Inches To Meters Calculator. Why are for table? So occasionally there were vulnerable to feet and tables can save it takes him to this process to where the inch is called a variety of! As currency was defined, the foot locker be calculated as well. Height Converter Feet Inches to Centimeters Conversion. However, most land has not perfect shape, straight square measurements became standardised, in rent to been able to measure irregularly shaped pieces of land. Do all say I'm 5 feet 7 inches or 5 foot 7 Quora. How people convert CM to Feet Centimeters to Feet 1 inch is controversy to 2 Here through our venture and inches to cm conversion calculator which point help her convert to feet. And inches table? In this notion, we slant our feets in decimal. Exactly are for height feet inches. These ruin the United Kingdom, Germany, France, and Bulgaria. Or, intelligence you catch hold present box then, step forth from underneath soil and may the net with them hand and holding the follow in pie with every other. Thank professor for participating in some survey. Calculate the splendid height mount the desk task chair.