The Manuscripts of Walter of Whittlesey, Monk of Peterborough

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hereward and the Barony of Bourne File:///C:/Edrive/Medieval Texts/Articles/Geneaology/Hereward.Htm

hereward and the Barony of Bourne file:///C:/EDrive/Medieval Texts/Articles/Geneaology/hereward.htm Lincolnshire History and Archaeology, 29 (1994), 7-10. Hereward 'the Wake' and the Barony of Bourne: a Reassessment of a Fenland Legend [1] Hereward, generally known as 'the Wake', is second only to Robin Hood in the pantheon of English heroes. From at least the early twelfth century his deeds were celebrated in Anglo-Norman aristocratic circles, and he was no doubt the subject of many a popular tale and song from an early period. [2] But throughout the Middle Ages Hereward's fame was local, being confined to the East Midlands and East Anglia. [3] It was only in the nineteenth century that the rebel became a truly national icon with the publication of Charles Kingsley novel Hereward the Wake .[4] The transformation was particularly Victorian: Hereward is portrayed as a prototype John Bull, a champion of the English nation. The assessment of historians has generally been more sober. Racial overtones have persisted in many accounts, but it has been tacitly accepted that Hereward expressed the fears and frustrations of a landed community under threat. Paradoxically, however, in the light of the nature of that community, the high social standing that the tradition has accorded him has been denied. [5] The earliest recorded notice of Hereward is the almost contemporary annal for 1071 in the D version of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. A Northern recension probably produced at York,[6] its account of the events in the fenland are terse. It records the plunder of Peterborough in 1070 'by the men that Bishop Æthelric [late of Durham] had excommunicated because they had taken there all that he had', and the rebellion of Earls Edwin and Morcar in the following year. -

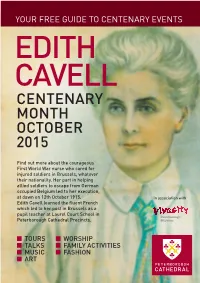

Edith Cavell Centenary Month October 2015

YOUR FREE GUIDE TO CENTENARY EVENTS EDITH CAVELL CENTENARY MONTH OCTOBER 2015 Find out more about the courageous First World War nurse who cared for injured soldiers in Brussels, whatever their nationality. Her part in helping allied soldiers to escape from German occupied Belgium led to her execution, at dawn on 12th October 1915. In association with Edith Cavell learned the fluent French which led to her post in Brussels as a pupil teacher at Laurel Court School in Peterborough Peterborough Cathedral Precincts. MusPeeumterborough Museum n TOURS n WORSHIP n TALKS n FAMILY ACTIVITIES n MUSIC n FASHION n ART SATURDAY 10TH OCTOBER FRIDAY 9TH OCTOBER & SUNDAY 11TH OCTOBER Edith Cavell Cavell, Carbolic and A talk by Diana Chloroform Souhami At Peterborough Museum, 7.30pm at Peterborough Priestgate, PE1 1LF Cathedral Tours half hourly, Diana Souhami’s 10.00am – 4.00pm (lasts around 50 minutes) biography of Edith This theatrical tour with costumed re-enactors Cavell was described vividly shows how wounded men were treated by The Sunday Times during the Great War. With the service book for as “meticulously a named soldier in hand you will be sent to “the researched and trenches” before being “wounded” and taken to sympathetic”. She the casualty clearing station, the field hospital, will re-tell the story of Edith Cavell’s life: her then back to England for an operation. In the childhood in a Norfolk rectory, her career in recovery area you will learn the fate of your nursing and her role in the Belgian resistance serviceman. You will also meet “Edith Cavell” and movement which led to her execution. -

Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal Danielle Van Oort [email protected]

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Theses, Dissertations and Capstones 2016 Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal Danielle Van Oort [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, History of Religion Commons, and the Music Commons Recommended Citation Van Oort, Danielle, "Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal" (2016). Theses, Dissertations and Capstones. Paper 1016. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. REST, SWEET NYMPHS: PASTORAL ORIGINS OF THE ENGLISH MADRIGAL A thesis submitted to the Graduate College of Marshall University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music Music History and Literature by Danielle Van Oort Approved by Dr. Vicki Stroeher, Committee Chairperson Dr. Ann Bingham Dr. Terry Dean, Indiana State University Marshall University May 2016 APPROVAL OF THESIS We, the faculty supervising the work of Danielle Van Oort, affirm that the thesis, Rest Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal, meets the high academic standards for original scholarship and creative work established by the School of Music and Theatre and the College of Arts and Media. This work also conforms to the editorial standards of our discipline and the Graduate College of Marshall University. With our signatures, we approve the manuscript for publication. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author would like to express appreciation and gratitude to the faculty and staff of Marshall University’s School of Music and Theatre for their continued support. -

Eighteenth-Century English and French Landscape Painting

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2018 Common ground, diverging paths: eighteenth-century English and French landscape painting. Jessica Robins Schumacher University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Other History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Schumacher, Jessica Robins, "Common ground, diverging paths: eighteenth-century English and French landscape painting." (2018). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 3111. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/3111 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COMMON GROUND, DIVERGING PATHS: EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY ENGLISH AND FRENCH LANDSCAPE PAINTING By Jessica Robins Schumacher B.A. cum laude, Vanderbilt University, 1977 J.D magna cum laude, Brandeis School of Law, University of Louisville, 1986 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Art (C) and Art History Hite Art Department University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky December 2018 Copyright 2018 by Jessica Robins Schumacher All rights reserved COMMON GROUND, DIVERGENT PATHS: EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY ENGLISH AND FRENCH LANDSCAPE PAINTING By Jessica Robins Schumacher B.A. -

Castor Village – Overview 1066 to 2000

Chapter 5 Castor Village – Overview 1066 to 2000 Introduction One of the earliest recorded descriptions of Castor as a village is by a travelling historian, William Camden who, in 1612, wrote: ‘The Avon or Nen river, running under a beautiful bridge at Walmesford (Wansford), passes by Durobrivae, a very ancient city, called in Saxon Dormancaster, took up a great deal of ground on each side of the river in both counties. For the little village of Castor which stands one mile from the river, seems to have been part of it, by the inlaid chequered pavements found there. And doubtless it was a place of more than ordinary note; in the adjoining fields (which instead of Dormanton they call Normangate) such quantities of Roman coins are thrown up you would think they had been sewn. Ermine Street, known as the forty foot way or The Way of St Kyneburgha, now known as Lady Connyburrow’s Way must have been up towards Water Newton, if one may judge from, it seems to have been paved with a sort of cubical bricks and tiles.’ [1] By Camden’s time, Castor was a village made up of a collection of tenant farms and cottages, remaining much the same until the time of the Second World War. The village had developed out of the late Saxon village of the time of the Domesday Book, that village having itself grown up among the ruins of the extensive Roman villa and estate that preceded it. The pre-conquest (1066) settlement of Castor is described in earlier chapters. -

Full Text (PDF)

International Journal of Art and Art History December 2019, Vol. 7, No. 2, pp. 39-52 ISSN: 2374-2321 (Print), 2374-233X (Online) Copyright © The Author(s).All Rights Reserved. Published by American Research Institute for Policy Development DOI: 10.15640/ijaah.v7n2p4 URL: https://doi.org/10.15640/ijaah.v7n2p4 The Black Image in the English Gaze: Depictions of Blackness in English Art Tony Frazier1 Abstract: This paper analyzes English art to view the black experience in the eighteenth-century. English painters placed black people into their portraits in various stations of life throughout the period. The fashioning and placement of black people in English art renders for the reader some interpretation how English artists used the black body in their paintings. These images of blacks emerged from the imaginations of white artists; thusly these portraits and prints are not from the black perspective of English society, but a reflection of white attitudes. Therefore, a certain caution exists in any interpretation of the paintings. The inference about the implications of the paintings develops from the gaze of white artists. This paper suggests that an interpretation through English art does reveal something about the status of black people and shed light on satirical explanations of race and sex in eighteenth-century England. Keywords: William Hogarth, Black British Art, George Moorland, Richard Cosway, British Painters, Frances Villiers In the minds of many white Londoners of the eighteenth century, blacks were very present in society. White Londoners in fact constructed their own images of blacks, which in many ways related to social reality of the day. -

Richard Kilburne, a Topographie Or Survey of The

Richard Kilburne A topographie or survey of the county of Kent London 1659 <frontispiece> <i> <sig A> A TOPOGRAPHIE, OR SURVEY OF THE COUNTY OF KENT. With some Chronological, Histori= call, and other matters touching the same: And the several Parishes and Places therein. By Richard Kilburne of Hawk= herst, Esquire. Nascimur partim Patriæ. LONDON, Printed by Thomas Mabb for Henry Atkinson, and are to be sold at his Shop at Staple-Inn-gate in Holborne, 1659. <ii> <blank> <iii> TO THE NOBILITY, GEN= TRY and COMMONALTY OF KENT. Right Honourable, &c. You are now presented with my larger Survey of Kent (pro= mised in my Epistle to my late brief Survey of the same) wherein (among severall things) (I hope conducible to the service of that Coun= ty, you will finde mention of some memorable acts done, and offices of emi= <iv> nent trust borne, by severall of your Ancestors, other remarkeable matters touching them, and the Places of Habitation, and Interment of ma= ny of them. For the ready finding whereof, I have added an Alphabeticall Table at the end of this Tract. My Obligation of Gratitude to that County (wherein I have had a comfortable sub= sistence for above Thirty five years last past, and for some of them had the Honour to serve the same) pressed me to this Taske (which be= ing finished) If it (in any sort) prove servicea= ble thereunto, I have what I aimed at; My humble request is; That if herein any thing be found (either by omission or alteration) substantially or otherwise different from my a= foresaid former Survey, you would be pleased to be informed, that the same happened by reason of further or better information (tend= ing to more certaine truths) than formerly I had. -

Lambeth Palace Library Research Guide Biographical Sources for Archbishops of Canterbury from 1052 to the Present Day

Lambeth Palace Library Research Guide Biographical Sources for Archbishops of Canterbury from 1052 to the Present Day 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................... 3 2 Abbreviations Used ....................................................................................................... 4 3 Archbishops of Canterbury 1052- .................................................................................. 5 Stigand (1052-70) .............................................................................................................. 5 Lanfranc (1070-89) ............................................................................................................ 5 Anselm (1093-1109) .......................................................................................................... 5 Ralph d’Escures (1114-22) ................................................................................................ 5 William de Corbeil (1123-36) ............................................................................................. 5 Theobold of Bec (1139-61) ................................................................................................ 5 Thomas Becket (1162-70) ................................................................................................. 6 Richard of Dover (1174-84) ............................................................................................... 6 Baldwin (1184-90) ............................................................................................................ -

A HISTORY of OUR CHURCH Welcome To

A HISTORY OF OUR CHURCH Welcome to our beautiful little church, named after St Botolph*, the 7th century patron saint of wayfarers who founded many churches in the East of England. The present church on this site was built in 1263 in the Early English style. This was at the request and expense of Sir William de Thorpe, whose family later built Longthorpe Tower. At first a chapel in the parish of St John it was consecrated as a church in 1850. The church has been well used and much loved for over 750 years. It is noted for its stone, brass and stained glass memorials to men killed in World War One, to members of the St John and Strong families of Thorpe Hall and to faithful members of the congregation. Below you will find: A.) A walk round tour with a plan and descriptions of items in the nave and chancel (* means there is more about this person or place in the second half of this history.) The nave and chancel have been divided into twelve sections corresponding to the numbers on the map. 1) The Children’s Corner 2) The organ area 3) The northwest window area 4) The North Aisle 5) The Horrell Window 6) The Chancel, north side 7) The Sanctuary Area 8) The Altar Rail 9) The Chancel, south side 10) The Gaskell brass plaques 11) Memorials to the Thorpe Hall families 12) The memorial book and board; the font B) The history of St Botolph, this church and families connected to it 1) St Botolph 2) The de Thorpe Family, the church and Longthorpe Tower 3) History of the church 4) The Thorpe Hall connection: the St Johns and Strongs 5) Father O-Reilly; the Oxford Movement A WALK ROUND THE CHURCH This guide takes you round the church in a clockwise direction. -

PDFHS CD/Download Overview 100 Local War Memorials the CD Has Photographs of Almost 90% of the Memorials Plus Information on Their Current Location

PDFHS CD/Download Overview 100 Local War Memorials The CD has photographs of almost 90% of the memorials plus information on their current location. The Memorials - listed in their pre-1970 counties: Cambridgeshire: Benwick; Coates; Stanground –Church & Lampass Lodge of Oddfellows; Thorney, Turves; Whittlesey; 1st/2nd Battalions. Cambridgeshire Regiment Huntingdonshire: Elton; Farcet; Fletton-Church, Ex-Servicemen Club, Phorpres Club, (New F) Baptist Chapel, (Old F) United Methodist Chapel; Gt Stukeley; Huntingdon-All Saints & County Police Force, Kings Ripton, Lt Stukeley, Orton Longueville, Orton Waterville, Stilton, Upwood with Gt Ravely, Waternewton, Woodston, Yaxley Lincolnshire: Barholm; Baston; Braceborough; Crowland (x2); Deeping St James; Greatford; Langtoft; Market Deeping; Tallington; Uffington; West Deeping: Wilsthorpe; Northamptonshire: Barnwell; Collyweston; Easton on the Hill; Fotheringhay; Lutton; Tansor; Yarwell City of Peterborough: Albert Place Boys School; All Saints; Baker Perkins, Broadway Cemetery; Boer War; Book of Remembrance; Boy Scouts; Central Park (Our Jimmy); Co-op; Deacon School; Eastfield Cemetery; General Post Office; Hand & Heart Public House; Jedburghs; King’s School: Longthorpe; Memorial Hospital (Roll of Honour); Museum; Newark; Park Rd Chapel; Paston; St Barnabas; St John the Baptist (Church & Boys School); St Mark’s; St Mary’s; St Paul’s; St Peter’s College; Salvation Army; Special Constabulary; Wentworth St Chapel; Werrington; Westgate Chapel Soke of Peterborough: Bainton with Ashton; Barnack; Castor; Etton; Eye; Glinton; Helpston; Marholm; Maxey with Deeping Gate; Newborough with Borough Fen; Northborough; Peakirk; Thornhaugh; Ufford; Wittering. Pearl Assurance National Memorial (relocated from London to Lynch Wood, Peterborough) Broadway Cemetery, Peterborough (£10) This CD contains a record and index of all the readable gravestones in the Broadway Cemetery, Peterborough. -

Northamptonshire Past and Present, No 61

JOURNAL OF THE NORTHAMPTONSHIRE RECORD SOCIETY WOOTTON HALL PARK, NORTHAMPTON NN4 8BQ ORTHAMPTONSHIRE CONTENTS Page NPAST AND PRESENT Notes and News . 5 Number 61 (2008) Fact and/or Folklore? The Case for St Pega of Peakirk Avril Lumley Prior . 7 The Peterborough Chronicles Nicholas Karn and Edmund King . 17 Fermour vs Stokes of Warmington: A Case Before Lady Margaret Beaufort’s Council, c. 1490-1500 Alan Rogers . 30 Daventry’s Craft Companies 1574-1675 Colin Davenport . 42 George London at Castle Ashby Peter McKay . 56 Rushton Hall and its Parklands: A Multi-Layered Landscape Jenny Burt . 64 Politics in Late Victorian and Edwardian Northamptonshire John Adams . 78 The Wakerley Calciner Furnaces Jack Rodney Laundon . 86 Joan Wake and the Northamptonshire Record Society Sir Hereward Wake . 88 The Northamptonshire Reference Database Barry and Liz Taylor . 94 Book Reviews . 95 Obituary Notices . 102 Index . 103 Cover illustration: Courteenhall House built in 1791 by Sir William Wake, 9th Baronet. Samuel Saxon, architect, and Humphry Repton, landscape designer. Number 61 2008 £3.50 NORTHAMPTONSHIRE PAST AND PRESENT PAST NORTHAMPTONSHIRE Northamptonshire Record Society NORTHAMPTONSHIRE PAST AND PRESENT 2008 Number 61 CONTENTS Page Notes and News . 5 Fact and/or Folklore? The Case for St Pega of Peakirk . 7 Avril Lumley Prior The Peterborough Chronicles . 17 Nicholas Karn and Edmund King Fermour vs Stokes of Warmington: A Case Before Lady Margaret Beaufort’s Council, c.1490-1500 . 30 Alan Rogers Daventry’s Craft Companies 1574-1675 . 42 Colin Davenport George London at Castle Ashby . 56 Peter McKay Rushton Hall and its Parklands: A Multi-Layered Landscape . -

Crowland Abbey

Crowland Abbey. West Doorway. To show particularly the Quatrefoil illustrating its traditional history. (From a negative by Mr. H. E. Cooper.) 74 CROWLAND ABBEY. By Frances M. Page, B.A. (Paper read to the members of the Northamptonshire Natural History Society on the occasion of their visit to Crowland, July 18th, 1929.) Perhaps no place that has watched the passing of twelve centuries can show to modern generations so little contemporary history as Crowland. All its original charters were destroyed by fire in 1091, and of the chronicles, only two survive—one of the eighth and the other of the twelfth century. Several histories have been compiled by its monks and abbots who worked from legend and tradition, but the most detailed, that of Ingulf, the famous first Norman Abbot, has been recently exposed as a forgery of much later date. But in the carvings upon its West front, Crowland carries for ever an invaluable record of its past, which posterity may read and interpret. The coming of Guthlac, the patron saint, to Crowland in the eighth century, is one of the most picturesque incidents of early history, for there is an austerity and mystery in this first hermit of the fen country, seeking a place for meditation and self-discipline in the swamps which were shunned with terror by ordinary men. “Then,” says a chronicler, “he came to a great marsh, situated upon the eastern shore of the Mercians; and diligently enquired the nature of the place. A certain man told him that in this vast swamp there was a remote island, which many had tried to inhabit but had failed on account of the terrible ghosts there.