7 a Preliminary Report on the 1980 and 1982 Field Seasons at Hacienda Grande (12 Psj7-5): Overview of Site History, Mapping and Excavations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

San Juan, Puerto Rico Via East Orange, New Jersey, Making It Work: Cultural Resource Management from Across an Ocean

SAN JUAN, PUERTO RICO VIA EAST ORANGE, NEW JERSEY, MAKING IT WORK: CULTURAL RESOURCE MANAGEMENT FROM ACROSS AN OCEAN Timothy R. Sara and Sharla C. Azizi The Louis Berger Group, Inc. ❐ ABSTRACT This paper describes the principal findings of an urban archaeological investigation conducted in a cultural resource management (CRM) context in Old San Juan, Puerto Rico (Sara and Marín Rom n 1999). The inves- tigation was prompted by the United States General Services Administration’s need to rehabilitate the Federal Courthouse and Post Office Building in the Old City. A major component of the investigation was the recovery and analysis of more than 16,000 Spanish colonial-period artifacts from urban fills beneath the building. The col- lection includes a total of 106 ceramic ware types, various small finds including gun flints, tobacco pipes, bone combs, die, and buttons, dietary faunal remains, and fine examples of European decorated glass. Analysis of these artifacts revealed that, despite strict trade laws imposed by the Spanish Crown, San Juan was well-integrated in the world economy early in its history. As a result of careful planning and coordination by project archaeologists and engineers, the remains of the Bastión de San Justo del Muelle, a massive seventeenth-century fortification work, was left in situ beneath the building during new construction. The successful outcome of the project was owed to the close coordination by the Federal and local government agencies, historic preservation consultants, and local specialists in Puerto Rican history and historical archaeology. Resumen Esta ponencia describir una programa de investigación arqueológica manejar en un contexto de Manejo de Recursos Culturales en el Viejo San de Puerto Rico (Sara y Marín Rom n 1999). -

National Historic Landmark Nomination Old San Juan

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 OLD SAN JUAN HISTORIC DISTRICT/DISTRITO HISTÓRICO DEL VIEJO SAN JUAN Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: Old San Juan Historic District/Distrito Histórico del Viejo San Juan Other Name/Site Number: Ciudad del Puerto Rico; San Juan de Puerto Rico; Viejo San Juan; Old San Juan; Ciudad Capital; Zona Histórica de San Juan; Casco Histórico de San Juan; Antiguo San Juan; San Juan Historic Zone 2. LOCATION Street & Number: Western corner of San Juan Islet. Roughly bounded by Not for publication: Calle de Norzagaray, Avenidas Muñoz Rivera and Ponce de León, Paseo de Covadonga and Calles J. A. Corretejer, Nilita Vientos Gastón, Recinto Sur, Calle de la Tanca and del Comercio. City/Town: San Juan Vicinity: State: Puerto Rico County: San Juan Code: 127 Zip Code: 00901 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: X Building(s): ___ Public-Local: X District: _X_ Public-State: X_ Site: ___ Public-Federal: _X_ Structure: ___ Object: ___ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 699 128 buildings 16 6 sites 39 0 structures 7 19 objects 798 119 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 772 Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form ((Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 OLD SAN JUAN HISTORIC DISTRICT/DISTRITO HISTÓRICO DEL VIEJO SAN JUAN Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Plaaces Registration Form 4. -

Hotel Palacio Provincial-Diplomatic History

Diplomatic and Government Research Palacio: edificio monumental destinado a ser sede de actos públicos, como congresos, exposiciones y actos gubernamentales. Palace: official residence of a sovereign, archbishop, bishop, or other exalted person, stately or official home. HOTEL PALACIO PROVINCIAL § According to the NRHP*, the Old San Juan Historic District is the oldest European settlement in Puerto Rico and the United States and the second one continuously inhabited in the American continent. It is historically documented that the Viejo San Juan had the first municipal government in the America continent after the city of Santo Domingo in neighboring Hispaniola. § The Old San Juan Historic District’s distribution and organization of the urban core by means of an HOTEL PALACIO orthogonal grid was inspired by European Renaissance ideas, particularly Italian of Classical PROVINCIAL extraction. § The Old San Juan Historic District has the oldest house, Christian temple, executive mansion, convent and military defenses in the United States. All of these structures can be found within this unique core that includes the Diputación Provincial building. *National Register of Historic Places To this day, the square bordering the Plaza de Armas is considered the heart of Old San Juan. In addition to this symbolic role as center of the urban core, the space continues to anchor the seats of both the island-wide and municipal governments, something it has done since the 17th century. By the 19th century and although the Spanish monarchy was not organized into independent branches (i e executive, legislative, and judicial), all the buildings relevant to the administration of the city and the island – Casa Alcaldiá , Real Intendencia and Diputacioń Provincial – were located around this neuralgic square. -

Application for Merchant's Registration Certificate Part I - Information of Merchant's Principal Office 1

Commonwealth of Puerto Rico Serial Number Form AS 2914.1 DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY Rev. Aug 30 11 APPLICATION FOR MERCHANT'S REGISTRATION CERTIFICATE PART I - INFORMATION OF MERCHANT'S PRINCIPAL OFFICE 1. Legal name of the corporation, partnership, individual owner (name, initial, last name) or other Receipt Stamp 2. Social security or employer identification number under which the income from this activity will be informed on the income tax return (It is mandatory to complete this line) 3. Telephone Ext. 4. E-mail address 5. Postal address (Post Office Box, Urbanization or Building, Number or Apartment, Street) Municipality / City State Zip Code Country 6. Principal office's physical address (Urbanization or Building, Number or Apartment, Street) Municipality / City State Zip Code Country 7. Type of organization: Individual Estate or Trust Corporation or Partnership 8. Date of incorporation or creation: Day Month Year 9. Closing date of your accounting period: Day Month 10. Aggregate business volume, estimated or projected, at the end of the current calendar year (It shall be the sum of the business volume of all your locations): $ , , . 11. Amount of locations / activities included in this application: 12. Amount of Schedules included with this application: (It cannot be less than one) PART II - LOCATIONS / ACTIVITIES Indicate the information for each one of the locations operated by the business (submit Schedule AS 2914.1 if necessary). - * - You shall complete all lines of this part in order to process the application. - * - 13. Trade name or "DBA" 14. Type of registration certificate requested (Check one): Merchant Mobile business Temporary business Exhibitor If you checked Temporary Business or Exhibitor, indicate:(From: Day Month Year To: Day Month Year ) 15. -

Experience the Life of South America and Caribbean Islands

Experience the life of South America and Caribbean Islands Beautiful weather rich cultures wonderful people spectacular sites to visit Tour presented by Cristina Garcia, Julie Hale, Laura Hamilton, Lupita Zeferino, Ramona Villavicencio You deserve a vacation of a lifetime Focus South America and the Caribbean will leave you enchanted by the fabulous landscapes, rich cultures and beautiful people. A native and expert guide your tour to each region providing you and your group with the experience of a lifetime. Points of Focus Itinerary Day Port Arrive Depart 1. Ft. Lauderdale --------- 5:00pm 2. At Sea --------- ---------- 3. Puerto Rico 1:30 12:00 midnight 4. Martinique 7:00am 7:00pm 5. Trinidad 8:00am 6:00pm 6. At Sea --------- ---------- 7. At Sea --------- ---------- 8. Cruising Amazon 9:00am 9:00pm 9. Santarem, Brazil 7:00am 10:00pm 10. Cruising Amazon 9:00am 9:00pm 11. Mauaus, Brazil 7:00pm 7:00pm 12.-14. Cruising Amazon 9:00am 4:00pm 15. Iquitos Peru 8:00am 2:00pm 16. Back to Ft. Lauderdale, Florida 9:00am ----------- Inquitos, Peru to Ft. Lauderdale Departure Arrival Airline Flight Travel Time Inquitos, Peru Ft. Lauderale Aero 2118 2 stops next day arrival change planes Delta Air Lines 274/1127 in Lima, Peru and Atlanta Total travel time: 15 h4s. 19 min. Price One way total: $1,346.00 Cruise Itinerary Details Ship Name: Paradise Cruise Line Enchantment of Seas Sailing Date: May 2004, June, 2004, July 2004, August 2004, September 2004 and more etc. Staterooms From: Interior Ocean view Balcony Suite $ 314 $ 426 $ 689 $ 694 Cruise Description Aboard the Paradise Cruise Line leaving Ft. -

BOLETÍN DE LA REAL SOCIEDAD GEOGRÁFICA Tomo CLVI 2021

DESARROLLO URBANÍSTICO DEL VIEJO SAN JUAN. PUERTO RICO URBAN DEVELOPMENT IN OLD SAN JUAN. PUERTO RICO Dr. Miguel A. Sánchez-Celada 1 INTRODUCCIÓN Según Friedrich Ratzel, la tarea fundamental del geógrafo es entender la relación que se establece entre el medio y los grupos sociales que lo habitan en cada zona específica, lo que los obliga a asumir comportamientos y actua- ciones diferentes en correspondencia con ese medio físico y cultural, a partir de este principio es que se pueden establecer diferentes paisajes geográficos. Por supuesto, sin llegar a la pretensión de la geopolítica clásica de hacer corresponder las posibilidades de desarrollo y expansión de los países a su posición en el espacio geográfico, se pretende en este artículo explicar el de- sarrollo urbano del centro histórico más emblemático de Puerto Rico, el Viejo San Juan, a partir de las características físicas de su emplazamiento y a su devenir histórico desde la conquista hasta la actualidad. Hasta hace relativamente poco tiempo los estudios sobre centros urbanos se referían principalmente al análisis descriptivo de datos primarios obtenidos en investigaciones en el terreno, además de la utilización de datos numéricos de demografía y econometría, no entendiendo a la ciudad como un ente vivo y 1 Universidad de Puerto Rico. Facultad de Ciencias Sociales. Dpto. de Geografía. miguel.sanchez11@ upr.edu Recibido: 20/05/2020. Aceptada versión definitiva: 17/11/2020. Boletín de la R.S.G., CLVI, 2021 (173-201) 174 MIGUEL A. SÁNCHEZ-CELADA complejo, que crece a partir de sus características internas y evoluciona a par- tir de externalidades. Por ejemplo, en las investigaciones llevadas a cabo en Brasil «… en los últimos 30 años del siglo XX se pasó de un énfasis centrado en los estudios de las dinámicas demográficas durante la década de 1960 y el inicio de la de 1970, a un énfasis en los estudios sobre la dinámica económica en la déca- da de 1970. -

Chapter 4 Legibility and Continuity in the Built Environment

Chapter 4 Legibility and Continuity in the Built Environment Michael R. King and Elise de Jong 4.1 Introduction When people are asked about wayfi nding, they usually respond with “signs.” Wayfi nding has become shorthand for adding signs to help people on their way. And yet, wayfi nding is so much more. According to Massimo Vignelli, author of the 1972 New York City subway map, Any sign is an admission of architectural failure. (Busch 2007 ) This chapter discusses wayfi nding with emphasis on design considerations rather than signage. It focuses on two paramount themes in community wayfi nding: legi- bility and continuity . Legibility revolves around reading. We “read” streets and cit- ies in much the same way that we read landscapes and maps. Water fl ows downhill from hills toward creeks. Thicker lines on maps represent higher concentrations. We look for clues that tell us where we are, what others are doing, where we want to go, and how to get there. The clues are context, network, and markers. Continuity is about consistency—in design, colors, signs, structure, and phases. Driving along the highway you typically encounter a consistent set of signs. Crosswalks are typically the same wherever you might be. Bike lanes are consis- tently green (or red or blue depending on the country). Trolley tracks indicate the presence of transit (or in some cases the former presence of transit). When these markers are placed consistently and continually along a path, wayfi nding is enhanced. M. R. King , RA (*) Traffi cCalmer , Brooklyn , NY , USA e-mail: miking@traffi ccalmer.com E. -

![USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form Linea Avanzada [Advanced Defense Line] San Juan, Puerto Rico Page #2](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8410/usdi-nps-nrhp-registration-form-linea-avanzada-advanced-defense-line-san-juan-puerto-rico-page-2-2488410.webp)

USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form Linea Avanzada [Advanced Defense Line] San Juan, Puerto Rico Page #2

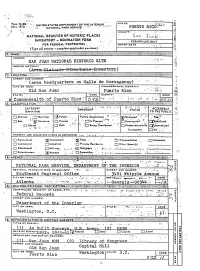

USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form Linea Avanzada [Advanced Defense Line] San Juan, Puerto Rico Page #2 4. National Park Service I, hereby certify that this property is: V entered in the National Register __ See continuation sheet __ determined eligible for the _ National Register __ determined not eligible for the __ National Register __ removed from the National Register __ other (explain): _ , iJ Signature of Keeper Date of Action 5. Classification Ownership of Property: public-State Category of Property: district Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 2 0 buildings (Redoubt San Geronimo and San Geronimo Powderhouse) 1 0 sites (Remnants of Bridgehead San Antonio) 1 0 structures (Battery Escambron) 0 0 objects 4 0 Total Number of contributing resources previously listed in the National Register / Name of related multiple property listing: N/A 6. Function or Use Historic Functions Cat:Defense Sub: fortification Defense arms storage Recreation museum Current Functions Cai:Recreation Sub: Outdoor recreation Vacant/Not in use USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form Linea Avanzada [Advanced Defense Line] San Juan, Puerto Rico Page #3 7. Description Architectural Classification: Spanish Colonial Materials foundation: stone walls: rubble masonry/brick roof: brick other: 8. Statement of Significance Applicable National Register Criteria: Criteria A: Property is associated with events that have made a significant contribution to the broad patterns of our history. Criterion C: Property embodies the distinctive characteristics of a type, period, or method of construction or represents the work of a master, or possesses high artistic values, or represents a significant and distinguishable entity whose components lack individual distinction. -

Washington CODE Exc«Iunt Good CONDITION (Chuck Onm) AU«R«D Unolt.R.D

STATE: frt°rm l^6 "'• '"• UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR* (Oct. 1772) - , i _::_.. v NATIONAL PARK SERVICE- PUERTO \ f COUNTY: NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM '•• FOR NPS USE ONLY "''•'•• FOR FEDERAL PROPERTIES _ •- ENTRY DATE (Type ail entries - complete applicable, sections) COMMON: SAN JUAN NATIONAL' HISTORIC SITE : ;..•*» ••- AND/OR HISTORIC: • Ur*tt-4ii**xw?4-e--^^ STREET AND NUMBER: (area headquarters on Calle de Norzagaray) CITY OR TOWN: CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT: . Old San Juan Puerto Rico STATE: CODE COONTY: CODE ra Commonwealth :of -Puerto "Rica '- CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS r ACCESSIBLE (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC District . f~] Building Public Acquisition-: c Occupied ' " Site *" '^T1 Structure Q) Privote '" CJtrrProcess" "? ' Unoccupied" ** j-» - • , . ^. .•. • D Object Both '.' ; 'f~1 Being Considered in progress . PRESENT USE (Chock One or Motor a» Appropriate) „, C~l Agriculturol nil Government (3 Transportation [~~1 Commerciol (~1 Industrial Private R»tidenc Q Other Q Edueotionol ' ,Q Military; r~] Entertainment [J] Mys«um NATIONAL PARK SERVICE, DEPARTKENT-OFr THE INTERIOR REGIONAl. HEADQUARTERS: (II applicable). '"*iv STREET AND NUMBER: '• Southeast Regional Office Whipple Avenue CITY OR TOWN: ..* . .-<••». CPDE. Atlanta COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETCl; Federal Records (A STREET AND NUMBER: Department of the Interior CITY OR TOWN: STATE; CODE V/ashington, D.G. :R£PR ES EKTATtON^N E TITLE OF SURVEY: AS Built -Sui-veya, H T S. 'Armyy. (2) -HABS DATE OF SURVEY? Fed.ro) Stote f"l County DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS: •San Jnan NHS Library of Congre: STREET AND NUMBER: Capital Hill i Old San Juan r CITY OR TOWN: Puerto Rico Washington CODE Exc«IUnt Good CONDITION (Chuck Onm) AU«r«d Unolt.r.d DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (it known) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE ""——~~~ H-200 EL MORKO (Castillo de San Felipe. -

Guide to Puerto Rican Records in the National Archives at New York City

GUIDE to PUERTO RICAN RECORDS in the NATIONAL ARCHIVES NEW YORK CITY August 2013 Cover Photo: Aerial photo of San Juan, RG 77 Records of the Office of the Chief of Engineers. Table of Contents Introduction 1 Census RG 29 Census Bureau, Special Censuses of Puerto Rico, 1935 2 Nonpopulation Census Schedules: Nonfarm Livestock, 1930 3 Legal RG 21/578 District Courts of the United States, 1897-1995 4 Criminal Cases Civil Cases Bankruptcy Cases Admiralty Cases Naturalization Records RG 118 Office of the U.S. Attorneys, 1987-1992 8 Military RG 77 Office of the Chief of Engineers, 1896-1950 9 RG 156 Office of the Chief of Ordnance, 1898-1904 11 RG 181 Naval Districts and Shore Establishments, 1898-1960 12 RG 338 U.S. Army Commands, 1952-1962 16 RG 392 U.S. Army Coast Artillery Districts and Defenses, 1901-1919 18 Social and Economic Development RG 4 U.S. Food Administration, 1917-1919 19 RG 9 National Recovery Administration, 1933-1936 20 RG 36 U.S. Customs Service, Customhouses and Collection Districts, Puerto Rico, 1900-1903 25 RG 95 U.S. Forest Service, Caribbean National Forrest, 1929-1961 26 RG 100 Occupational Safety and Health Administration [OSHA], 1977 27 RG 155 Wage and Hour Division, 1939-1945 28 RG 164 Cooperative State Research Service, 1901-1938 30 Agricultural Experiment Station at Mayaguez RG 187 National Resource Planning Board, 1941-1943 31 RG 188 Office of Price Administration, 1942-1946 33 RG 252 Office of the Housing Expediter, 1942-1953 37 RG 323 Puerto Rico Reconstruction Administration, 1935-1955 38 Government and Political Administration RG 26 U.S. -

Foundation Document Overview San Juan National Historic Site Puerto Rico

NatioNal Park Service • U.S. DePartmeNt of the iNterior Foundation Document Overview San Juan National Historic Site Puerto Rico Contact Information For more information about the San Juan National Historic Site Foundation Document, contact: [email protected] or 787-729-6777 or write to: Superintendent, San Juan National Historic Site, 501 Calle Norzagaray, San Juan, PR 00901 Purpose Significance Significance statements express why San Juan National Historic Site resources and values are important enough to merit national park unit designation. Statements of significance describe why an area is important within a global, national, regional, and systemwide context. These statements are linked to the purpose of the park unit, and are supported by data, research, and consensus. Significance statements describe the distinctive nature of the park and inform management decisions, focusing efforts on preserving and protecting the most important resources and values of the park unit. • San Juan National Historic Site preserves and protects an internationally significant example of a complex system of fortifications built by the Spanish Crown to defend its empire and interests in the New World. • San Juan National Historic Site is a premiere example of military engineering and architectural design and is one of the best preserved examples of Spain’s grand colonial coastal and land defense system in the Americas. • The fortifications have been adapted architecturally and Representing 500 years of history and functionally over the past 500 years to serve as a center of Spanish and U.S. political, social, and military global influence. the importance of the island’s strategic location in the Caribbean, • Designated in 1983 as a world heritage site, San Juan National Historic Site is a potent symbol of cultural heritage linking the SAN JUAN NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE history of Puerto Rico to the Hispanic culture and provides a preserves, protects, and interprets the common identity with other Latin American countries. -

Tips for Transitioning to Puerto Rico* Trinity Church Welcomes Everyone, Those Who Are Born in Puerto Rico and Those Who Are New to the Island

Tips for Transitioning to Puerto Rico* Trinity Church welcomes everyone, those who are born in Puerto Rico and those who are new to the island. We recognize that many of those who live near Dorado and are most comfortable worshipping in English are not from Puerto Rico, and may have only lived on the island a short time. Some of us in that category have collected† the following information, to help you more easily transition to life in the Caribbean. We share these tips because we know that any transition like moving to Puerto Rico presents many challenges, and we want to help you enjoy the journey! We'll be here for you as you experience it. If you have found this document randomly on the internet, please visit http://trinitychurchdorado.org/ or our Facebook page. Contents ¡BIENVENIDOS! WELCOME to Puerto Rico! ................................................................................. 2 Things to Know Immediately Upon Arrival ................................................................................. 2 Finding housing ..................................................................................................................................... 2 Postal mail and packages ................................................................................................................... 4 Getting plugged in to the community ............................................................................................. 4 Schools .....................................................................................................................................................