Developing Living Streets in Highland Park

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exploring Changes to Cycle Infrastructure to Improve the Experience of Cycling for Families

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UWE Bristol Research Repository Exploring changes to cycle infrastructure to improve the experience of cycling for families Dr William Clayton1 Dr Charles Musselwhite Centre for transport and Society Centre for Innovative Ageing Faculty of Environment and Technology School of Human and Health Sciences University of the West of England Swansea University Bristol, UK Swansea, UK BS16 1QY SA2 8PP Tel: +44 (0)1792 518696 Tel: +44 (0) 117 32 82316 Web: www.drcharliemuss.com Email: [email protected] Twitter: @charliemuss Website: www.uwe.ac.uk/et/research/cts Email: [email protected] KEYWORDS: Cycling, infrastructure, motivation, families, behaviour change. Abstract: Positive changes to the immediate cycling environment can improve the cycling experience through increasing levels of safety, but little is known about how the intrinsic benefits of cycling might be enhanced beyond this. This paper presents research which has studied the potential benefits of changing the infrastructure within a cycle network – here the National Cycle Network (NCN) in the United Kingdom (UK) – to enhance the intrinsic rewards of cycling. The rationale in this approach is that this could be a motivating factor in encouraging greater use of the cycle network, and consequently help in promoting cycling and active travel more generally amongst family groups. The project involved in-depth research with 64 participants, which included family interviews, self-documented family cycle rides, and school focus groups. The findings suggest that improvements to the cycling environment can help maintain ongoing motivation for experienced cycling families by enhancing novel aspects of a routine journey, creating enjoyable activities and facilitating other incidental experiences along the course of a route, and improving the kinaesthetic experience of cycling. -

Download Toolkit for a School Route Review

PRINTER-FRIENDLY VERSION DEWCH I NI GERDDED I’R CYMRU YS GOL Toolkit for a School Route Review A step by step guide to running a School Route Review Help us create a walking nation We are Living Streets Cymru, part of the UK charity for everyday walking and the people behind the Walk to School Campaign. We’ve got a big ambition: that every child that can, walks to school. Useful links Run your own School Route Review livingstreets.org.uk/who-we-are/wales Advertise your event – download a poster to put up at school. Invite parents, Councillors and local residents – download template letters in Welsh or English. Living Streets - Walk to School livingstreets.org.uk/what-we-do/walk-to-school Living Streets - WOW Walking Challenge livingstreets.org.uk/what-we-do/projects/wow Living Streets - Park and Stride Guide livingstreets.org.uk/media/2035/park-and-stride-print.pdf Active Travel Act wales.gov.uk/active-travel Sustrans - Active Journeys sustrans.org.uk/active-journeys-school-wales The Daily Mile thedailymile.co.uk/ Keep Wales Tidy keepwalestidy.cymru If you would like this toolkit or further information by email please contact [email protected] Contents What is a School Route Review? 2 Why carry out a School Route Review? 3 Step 1 - getting ready to review 5 Classroom ideas Lesson plan Step 2 - walking the walk 11 Carrying out the School Route Review Step 3 - reporting the review 14 Case studies 16 Malpas Court Primary School - Newport St Mellons Church in Wales Primary School - Cardiff Nant-y-Parc Primary School - Caerphilly School Route Review Checklist 22 Poster 26 1 What is a School Route Review? A School Route Review is a great way of discovering some of the things that might stop families walking to school. -

Highway 17 and 69 Controlled Access Highway Response

Sudbury Cyclists Union March 28, 2014 Re: Route Planning Study, Highway 17 from Sudbury to Markstay and Highway 69 from the Estaire Road Interchange to Highway 17 The Sudbury Cyclists Union (SCU) has serious concerns about how the implementation of controlled access highways have affected cyclists in the Sudbury region. We also have some specific concerns about the implementation of this project as it relates to the safety of cyclists. The intent of all provincial roadwork is to improve the safety of its users. Traditionally, the focus has been on the safety of motorized traffic. The safety of pedestrians and cyclists has been long neglected on our highways. On page 2.1 of your “Study Design Report”, you note that to “promote a multimodal transportation network” is a key provincial responsibility” as is to “be a leader in road safety”. The sole intent of implementing controlled access highways is to facilitate the safe movement of motorized traffic. While implementing such highways draws dangerous traffic away from more local routes that are used by cyclists, alternative safe and convenient routes for cyclists are often an afterthought and are not an integral part of the planning process. An example is the Highway 69 corridor leading south from the City of Greater Sudbury that has been built without guaranteeing an alternative right of way for cyclists wishing to travel south. This controlled access highway has closed off access for non-motorized users to several towns and tourist areas, including the town of Killarney and the iconic Killarney Provincial Park. In other provinces, in particular in Western Canada, major motor routes similar to our controlled highways have paved shoulders that are used by cyclists. -

Planning for Active Transportation in the Western United States: an Alternative Future for Cache Valley, Utah

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 8-2018 Planning for Active Transportation in the Western United States: An Alternative Future for Cache Valley, Utah Stephanie A. Tomlin Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the Environmental Design Commons, and the Landscape Architecture Commons Recommended Citation Tomlin, Stephanie A., "Planning for Active Transportation in the Western United States: An Alternative Future for Cache Valley, Utah" (2018). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 7195. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/7195 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PLANNING FOR ACTIVE TRANSPORTATION IN THE WESTERN UNITED STATES: AN ALTERNATIVE FUTURE FOR CACHE VALLEY, UTAH by Stephanie A. Tomlin A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in Bioregional Planning Approved: Bartlett Warren-Kretzschmar, Ph.D. Richard Toth, M.L.A. Major Professor Committee Member Jordy Guth, M.S. Mark R. McLellan, Ph.D. Committee Member Vice President for Research and Dean of the School of Graduate Studies UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 2018 ii Copyright © Stephanie A. Tomlin, 2018 All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Planning for Active Transportation in the Western United States: An Alternative Future for Cache Valley, Utah by Stephanie A. Tomlin, Master of Bioregional Planning Utah State University, 2018 Major Professor: Bartlett (Barty) Warren-Kretzschmar, Ph.D. -

Shared Streets and Alleyways – White Paper

City of Ashland, Ashland Transportation System Plan Shared Streets and Alleyways – White Paper To: Jim Olson, City of Ashland Cc: Project Management Team From: Adrian Witte and Drew Meisel, Alta Planning + Design Date: February 2, 2011 Re: Task 7.1.O White Paper: “Shared Streets and Alleyways” - DRAFT Direction to the Planning Commission and Transportation Commission Five sets of white papers are being produced to present information on tools, opportunities, and potential strategies that could help Ashland become a nationwide leader as a green transportation community. Each white paper will present general information regarding a topic and then provide ideas on where and how that tool, strategy, and/or policy could be used within Ashland. You will have the opportunity to review the content of each white paper and share your thoughts, concerns, questions, and ideas in a joint Planning Commission/Transportation Commission meeting. Based on discussions at the meeting, the material in the white paper will be: 1) Revised and incorporated into the alternatives analysis for the draft TSP; or 2) Eliminated from consideration and excluded from the alternatives analysis. The overall intent of the white paper series is to explore opportunities and discuss the many possibilities for Ashland. Shared Streets Introduction Shared Streets aim to provide a better balance of the needs of all road users to improve safety, comfort, and livability. They are similar to European concepts such as the Dutch based ‘Woonerf’ and the United Kingdom’s ‘Home Zone’, with some distinct differences. This balance is accomplished through integration rather than segregation of users. By eschewing many of the traditional roadway treatments such as curbs, signs, and pavement markings, the distinction between modes is blurred. -

A Feasibility Study of GIS-Based Analyses of Cycling Infrastructure

Build it: A Feasibility Study of GIS-Based Analyses of Cycling Infrastructure A thesis submitted by Ian Thistle In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Urban and Environmental Policy and Planning Tufts University February 2016 Adviser: Mary Davis Reader: Barbara Parmenter Table of Contents List of Figures ...................................................................................... iv List of Tables ........................................................................................ v Abstract .................................................................................................. vi Acknowledgements ................................................................................. vii Chapter 1: Introduction ............................................................................ 1 Chapter 2: Literature Review.................................................................... 4 Benefits of Cycling ................................................................................ 4 How can cities influence mode choice towards biking? ......................... 6 Evaluating Road Infrastructure for Cycling ............................................ 9 Analysis of Street Networks: “Build it! But Where?” ............................ 13 Chapter 3: Methods ............................................................................... 17 Step 1: Selecting the comparison methodologies ............................... 19 Step 2: Selecting the sample ............................................................. -

Smart Choices for Cities: Cycling in the City

Smart choices for cities Cycling in the City Smart choices for cities Cycling in the City Pictures © Shutterstock, 2016, pages: 1, 14, 15, 20, 22. 2 Smart choices for cities Cycling in the City Table of contents Preface. 4 Introduction . 5 The city is changing . 5 Why cycling? . 8 An integrated approach to cycling provision in the urban environment. 9 Infrastructure.and.equipment. 10 Introduction. 10 Cycling safety . 10 Where do most accidents happen? . 11 Senior cyclists and safety . 12 Equipment . 12 Implications for infrastructure . 12 Building blocks for safe infrastructure . 14 Recognisability . 16 Specific infrastructural situations . 16 Multi-modal Transport. 16 Bicycle Congestion . 18 Bicycle Theft . 18 Supporting.Actions. 19 Introduction. 19 Building an organization in (local) government . 19 Working with stakeholders . 20 Cycling Association . 20 Employers: Bicycle to work . 20 Cycle Marketing . 20 Education . 21 Insights in cycling behaviour . 21 Gathering data . 21 Cycling in traffic models . 21 From.ideas.to.policy:.Recommendations.for.approaching.investments.in.cycling . 22 Bibliography. 24 Notes. 26 3 Smart choices for cities Cycling in the City Preface Thank you for reading the eighth and final policy analysis of Over 70% of all Europeans live in cities and cities are the CIVITAS WIKI Policy Analysis Series. becoming increasingly congested. Citizens suffer from poor air quality and noise, which makes the cities less liveable. The mission of the CIVITAS WIKI project was to provide This document provides information about measures that can information on clean urban transport and the CIVITAS be taken in order to increase the use of cycling as a transport Initiative to EU city planners, decision-makers and citizens. -

FLOW Portfolio of Measures: the Role of Walking and Cycling in Reducing

THE ROLE OF WALKING AND CYCLING IN REDUCING CONGESTION A PORTFOLIO OF MEASURES A PORTFOLIO OF MEASURES FLOW DOCUMENT TITLE The Role of Walking and Cycling in Reducing Congestion: A Portfolio of Measures AUTHORS Thorsten Koska, Frederic Rudolph (Wuppertal Institut für Klima, Umwelt, Energie gGmbH); Case Studies: Benjamin Schreck, Andreas Vesper (Bundesanstalt für Straßenwesen), Tamás Halmos (Budapesti Közlekedési Központ), Tamás Mátrai (Budapesti Műszaki és Gazdaságtudományi Egyetem), Alicja Pawłowska (Municipality of Gdynia), Jacek Oskarbski (Politechnika Gdanska), Benedicte Swennen (European Cyclists’ Federation), Nora Szabo (PTV AG), Graham Cavanagh (Rupprecht Consult GmbH), Florence Lepoudre (Traject), Katie Millard (Transport Research Laboratory), Martin Wedderburn (Walk21), Miriam Müller, David Knor (Wuppertal Institut für Klima, Umwelt, Energie gGmbH) CONTACT Project coordinator: Rupprecht Consult Bernard Gyergyay: [email protected] Kristin Tovaas: [email protected] Project dissemination manager: Polis Daniela Stoycheva: [email protected] CITATION FLOW Project (2016). The Role of Walking and Cycling in Reducing Congestion: A Portfolio of Measures. Brussels. Available at http://www.h2020-flow.eu. IMAGE DISCLAIMER The images in this document are used as a form of visual citation to support and clarify statements made in the text. The authors have made great effort to provide credit for every image used. If, despite our efforts, we have not given sufficient credit to the author of any images used, please contact us directly at [email protected] LAYOUT PEAK Sourcing DATE July 2016 The sole responsibility for the content of this publication lies with the authors. It does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the European Union. Neither the INEA nor the European Commission is responsible for any use that may be made of the information contained therein. -

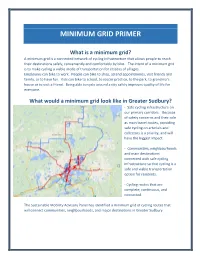

Minimum Grid Primer

MINIMUM GRID PRIMER What is a minimum grid? A minimum grid is a connected network of cycling infrastructure that allows people to reach their destinations safely, conveniently and comfortably by bike. The intent of a minimum grid is to make cycling a viable mode of transportation for citizens of all ages. Employees can bike to work. People can bike to shop, attend appointments, visit friends and family, or to have fun. Kids can bike to school, to soccer practice, to the park, to grandma’s house or to visit a friend. Being able to cycle around a city safely improves quality of life for everyone. What would a minimum grid look like in Greater Sudbury? - Safe cycling infrastructure on our primary corridors. Because of safety concerns and their role as main travel routes, providing safe cycling on arterials and collectors is a priority, and will have the biggest impact. - Communities, neighbourhoods and main destinations connected with safe cycling infrastructure so that cycling is a safe and viable transportation option for residents. - Cycling routes that are complete, continuous, and connected. The Sustainable Mobility Advisory Panel has identified a minimum grid of cycling routes that will connect communities, neighbourhoods, and major destinations in Greater Sudbury. Why is it important to have safe cycling on our busiest streets first? A transportation network relies on primary routes that secondary routes feed into and out of. This is true of any type of transportation, including cycling. The primary network needs to be constructed first, otherwise the transportation network is fragmented - the secondary routes do not connect to anything. -

Cycling Infrastructure Version 1

Cycling VERSION 1 infrastructure Cycling infrastructure In this chapter 01 Introduction 5 Kerbside activity 33 07 02 Choosing the right facility 6 General Design 35 08 2.1 Design parameters 6 8.1 Design controls 35 2.2 Types of cycle facility 8 8.2 Horizontal and vertical alignment 39 8.3 Widths and clearances 41 03 Approved facilities within the road reserve 11 8.4 Construction 45 3.1 Separated cycleway (busy, fast, or heavy traffic) 11 8.5 Drainage 46 3.2 Separated cycleway (low volume and slow traffic) 14 8.6 Signs and markings 47 3.3 Alternatives requiring specific approval 15 8.7 Lighting 48 3.4 Mixed traffic streets 16 3.5 Cycle streets 16 Ancillary features 49 09 3.6 Pedestrian priority areas (cycling and pedestrians) 17 3.7 Interim facilities 20 Design for maintenance 52 10 Appendix A 04 Other infrastructure 22 Cycle parking 53 4.1 Buffered cycle lanes 22 A.1 Introduction 53 4.2 Cycle lanes 23 A.2 Bicycle Parking General principles 54 4.3 Cycle lanes between other traffic lanes 23 A.3 Categories of bicycle parking 56 4.4 Shared paths 24 A.4 Types of bicycle parking 58 A.5 Types of bicycle stands 64 05 Off road cycle paths 25 A.6 Bicycle parking placement 67 A.7 Bicycle parking access 68 06 Intersections 26 A.8 Bicycle stand materials 68 6.1 Cycleway intersections 27 A.9 Signage and wayfinding for bicycle parking 68 6.2 Roundabouts 27 A.10 Bicycle parking demand 69 6.3 Signalised intersections 28 A.11 Bicycle parking at public transport terminals 70 6.4 Unsignalised intersections 30 A.12 Bicycle parking provisioning process 71 6.5 Midblock crossing 31 A.13 Building and installation 72 6.6 Vehicle crossings 32 A.14 Operation and maintenance 72 5794_20.04.21 2 TDM | ENGINEERING DESIGN CODE 3 Cycling infrastructure 01 Introduction PURPOSE Cycling infrastructure includes facilities that are dedicated for cycle use, as well as specific standards for general infrastructure to meet the needs of cycle users. -

LCDS Chapter 6 Signs and Markings

London Cycling Design Standards [Chapter 6] Signs and markings | Contents 6. Signs and markings This chapter gives an overview of requirements on signing 6.2 Surface markings 06 to support cycling, both for dedicated infrastructure and 6.2.1 General requirements 06 for cyclists’ general use of the highway. 6.2.2 Lane markings 06 6.2.3 Give way markings 08 6.1 Signing requirements 01 6.2.4 Other markings for cycle tracks 09 6 .1.1 Signing principles 01 6.2.5 Cycle symbols and direction signing 10 6.1.2 Applying the principles 01 6.2.6 Coloured surfacing 13 6.1.3 Regulatory changes 02 6.1.4 Signs requiring enforcement 03 6.3 Signs 14 6.1.5 Signing to support wayfinding 04 6.3.1 Direction signs 14 6.3.2 Off-highway direction signs 16 6.3.3 Warning signs 16 6.3.4 Signs for pedestrian zones 17 6.3.5 Signs to minimise or avoid 18 6.3.6 Minimising sign clutter 18 6.3.7 Sign installation and mounting 21 6.4 Schedule of signs 23 Bibliography 29 Version control Version 1 (Dec 2014) – Published Q12 Version 2 (Sept 2016) – Amendments throughout following publication of TSRGD (2016) London Cycling Design Standards [Chapter 6] Signing requirements 01 Signing plays an important role in supporting and Figure 6.1 Key signing considerations in CLoS 6.1 Signing requirements enforcing safer, more comfortable, legible and coherent cycling infrastructure. Road signs and Factor Indicator Relates in this markings are defined, together, as ‘traffic signs’ chapter to 6.1.1 Signing principles within the Road Traffic Regulation Act 1984. -

To Stop the Use of Property Intentionally

Glossary of Planning Terms Access Management: Access picking fruit, feeding animals, or staying at management is the process of balancing a Bed & Breakfast on a farm. the competing needs of motor vehicle mobility and land access. Access Americans with Disabilities Act management provides access to land (ADA): A comprehensive, federal civil development while simultaneously rights law that prohibits discrimination on preserving the safe and efficient flow of the basis of disabilities in employment, traffic, including bicyclists and state and local government programs and pedestrians, on the roadway system. activities, public accommodations, transportation, and telecommunications. Accessory Dwelling Unit: An independent dwelling unit that is clearly Apartment: A dwelling unit used subordinate to a single-family detached exclusively for lease or rent as a residence. dwelling, as distinguished from a duplex or other two-family dwelling. It may be Archeological Resources: Places that internal or external to the main unit. have the potential to yield information about the past through study of the Adaptive Reuse: Rehabilitation or landscape and remains of previous human renovation of existing building(s) or intervention on the landscape. structures for any use(s) other than the present use(s). Architectural and Cultural Heritage: Places, people, objects, stories, traditions, Affordable Dwelling Unit: Refers to and ideas from and about the past that units required under the Affordable relate to us today. Dwelling Unit Ordinance, units are committed for a 30-year term as affordable Architectural and Historic Surveys: to households with incomes at 60 percent Studies of the properties within a or less of the area median income.