Medieval Education: a Bibliographical Essay

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monastic Schools in Myanmar – a Baseline Study

2014 – Monastic schools in Myanmar a baseline study Burnet Institute Myanmar & Monastic Education Development Group February 2014 MEC Baseline Report of Monastic Schools, 2014 February 2014 Lead authors are Hilary Veale from the Burnet Institute, Melbourne and Dr Poe Poe Aung from the Burnet Institute, Myanmar, with contributions from Professor Margaret Hellard, Dr Karl Dorning, Dr Freya Fowkes, Damien McCarthy, Paul Agius, Khin Hnin Oo, Than Htet Soe, and Yadanar Khin Khin Kyaw. Acknowledgements The Burnet Institute and the Monastic Education Development Group would like to thank Phaung Daw Oo School for their collaboration in this baseline assessment and for providing excellent data collection staff who worked tirelessly in the field, and completed data entry, checking and cleaning. We also wish to acknowledge and give thanks to all the principals, staff and students of monastic schools who generously gave up their time and shared their knowledge with us. Their kind hospitality was also much appreciated by our data collection teams. This survey would not have been possible without their participation and we hope that the findings from this survey will benefit them in the future, through the MEC project and beyond. This baseline study was supported through the Myanmar Education Consortium with funds from the Australian and UK Governments. This report should be cited as Burnet Institute and Monastic Education Development Group (2014), Monastic schools in Myanmar – a baseline study. Cover photograph: Monastic school classroom (Than Htet -

Situation Analysis of the Monastic Education System in Myanmar Final Report July 2015

Situation Analysis of the Monastic Education System in Myanmar Final Report July 2015 Daw Ohnmar Tin and Miss Emily Stenning Inside front cover Situation Analysis of the Monastic Education System in Myanmar Final Report July 2015 Daw Ohnmar Tin and Miss Emily Stenning Front cover images: Kanthaya Monastery (left), Shwe Yin Aye Monastery (right) Credit: Burnet Institute and MEDG Text and image copyright: Myanmar Education Consortium (MEC) 2016 Graphic design by Katherine Gibney | www.accurateyak.carbonmade.com Ohnmar Tin has worked as teacher, social welfare officer, child protection officer, educator, trainer and module writer for competency-based teacher training program for primary level untrained teachers in non-government sector and is now a freelance consultant. Her services include teacher training for untrained primary school teachers in non-government sector with various organisations such as Metta Development Foundation, Shalom Foundation, Pestalozzi Children Foundation and early grade reading assessment with the Departments of Basic Education and the World Bank; and kindergarten curriculum development with the Departments of Basic Education. She has been involved in various needs analysis, and participatory rapid appraisal research in various part of Myanmar. She has worked on end of cycle project evaluation exercises with organisations including World Vision, Save the Children, as well as local Kachin, Karen, Ar Khar, Larhu, Wa Baptist Conventions. Contact: [email protected] Emily Stenning is an independent education consultant who has lived and worked in Myanmar since 2013. She has 10 years experience of advising and delivering education policies and programmes. She has experience in a range of educational areas from teacher training through to innovative financing strategies, but her specialist area is looking at how to address the persistent barriers denying children access to quality education. -

Self-Knowledge in the Theology of Bernard Of

MY BELOVED IS MINE AND I AM HIS: SELF-KNOWLEDGE IN THE THEOLOGY OF BERNARD OF CLAIRVAUX A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Notre Dame in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by James U. DeFrancis, Jr. Ann W. Astell, Director Graduate Program in Theology Notre Dame, Indiana July 2012 © Copyright 2012 James U. DeFrancis, Jr. MY BELOVED IS MINE AND I AM HIS: SELF-KNOWLEDGE IN THE THEOLOGY OF BERNARD OF CLAIRVAUX Abstract by James U. DeFrancis, Jr. This dissertation examines the various forms and roles self-knowledge assumes in Bernard of Clairvaux’s overarching vision of the spiritual life. Previous scholarship on Bernard’s doctrine of self-knowledge has correctly emphasized the significance he attaches to humbling self-knowledge, or the soul’s honest self-recognition as a disfigured image of God, in the soul’s first conversion and the initial stages of its return to God. A certain scholarly preoccupation with this aspect of the abbot’s thought has, however, somewhat obscured the full breadth of Bernard’s teaching on self-knowledge and the diverse forms and roles it assumes across the various phases of the soul’s spiritual life, including those which both proceed and follow its first conversion. Prior to its first conversion, Bernard believes, the soul suffers not only from self- ignorance, but also from a self-deception, a false self-knowledge born of pride, by which it imagines itself superior to others and therefore not in need of conversion or healing. It is precisely because he recognizes the seductive power of this self-deception that Bernard so frequently insists upon the soul’s humbling recognition of its own sad disfigurement as James U. -

A Comparative Study on Students' Satisfaction

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Assumption Journals 271 A COMPARATIVE STUDY ON STUDENTS’ SATISFACTION BETWEEN NAUNG TAUNG MONASTIC HIGH SCHOOL AND KYAUK TA LONE PUBLIC HIGH SCHOOL IN SOUTHERN SHAN STATE, MYANMAR Ven. Pandita Dhaja Lankara1 YanYe2 Abstract: The purpose of this study was to compare the students’ satisfaction towards the school instruction, course, grading, test, guidance, rules, library, and assistance between Naung Taung monastic high school and Kyauk Ta Lone public high school in southern Shan state, Myanmar. The collected data were analyzed by using the descriptive statistics including Frequency, Percentage, Standard deviation Mean; and Inferential Independent Samples t-test (Two-tailed). The study found that the students’ satisfaction at both schools were high. Thus, the research also found that in general there was no significant difference of students’ satisfaction between Naung Taung monastic high school and Kyauk Ta Lone public high school in southern Shan state, Myanmar. However, significant difference of students’ satisfaction towards course, grading, test, rules, and assistance were also founded in two schools. Keywords: Students’ Satisfaction, Myanmar, Monastic High School Introduction Since the earliest days, Myanmar has highly regarded education as their property of life. Because of this opinion, Myanmar people, from the past to present, firmly hold the motto “no one can steal or take away the golden pot of wisdom from those who have educated.” Traditionally, Myanmar people have strongly relied on monastic education since the time of the Myanmar kings, and they also had significantly at that time (Han Tin, 2000). -

Cistercian and Monastic Studies 2017 C O N F E R E N C E

cistercian and monastic studies 2017 C O N F E R E N C E Western Michigan University Program and Schedule of Events In conjunction with the 52nd International Congress on Medieval Studies May 11–14, 2017 Thursday, May 11 | Lee Honors College Lounge Friday, May 12 | Lee Honors College Lounge 10:00 a.m. 10:00 a.m. Monks and the World: Political and Economic Activities Monastic Lives Presider: Jean Truax, Independent Scholar Presider: Martha Krieg, Independent Scholar St. Bernard of Clairvaux and the Crusades The Wrong Side of History: Thomas Becket and Aelred of Rievaulx Ryszard Gron, Archdiocese of Chicago Jean A. Truax, Independent Scholar Saint George’s Abbey in Gratteri - Ninian and the Rod of Aaron The First Cistercian Settlement in the Kingdom of Sicily? Chad Turner, Saint Joseph’s College Francesco Capitummino, Independent Scholar Exemplum as History: The Worlds of a Cistercian Nun Katherine Richman, Laboure College 1:30 p.m. Spirituality in Monastic Life 1:30 p.m. Presider: Hugh Feiss, OSB Dubious Sources in Monastic History “The Word Runs Swiftly”: Presider: Anne Lester, University of Colorado-Boulder The Symbolism of “Running” in Bernard and William The First Life of Bernard: Can we trust it? Isaac Slater, OCSO Brian Patrick McGuire, Independent Scholar Early Symptoms of Humanism in Bernard’s de Deligendo Deo Popular Perceptions of Cistercians vs. Trappists in late 19th Century Austria Luke Anderson, O. Cist, St. Mary’s Monastery Alcuin Schachenmayr, O. Cist, Pontifical Athanaeum Benedict XVI. The “Paradise of Inner Pleasure”: Heiligenkreuz The “Monastery” in Medieval Monastic Spirituality Mortifera salutacio: Herbert of Torres’ Version of the Devil’s Letter Greg Peters, Biola University Stefano Mula, Middlebury College 3:30 p.m. -

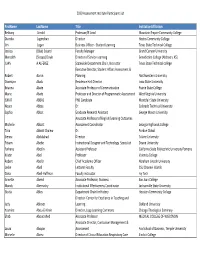

2020 Assessment Institute Participant List Firstname Lastname Title

2020 Assessment Institute Participant List FirstName LastName Title InstitutionAffiliation Bethany Arnold Professor/IE Lead Mountain Empire Community College Diandra Jugmohan Director Hostos Community College Jim Logan Business Officer ‐ Student Learning Texas State Technical College Jessica (Blair) Soland Faculty Manager Grand Canyon University Meredith (Stoops) Doyle Director of Service‐Learning Benedictine College (Atchison, KS) JUAN A ALFEREZ Statewide Department Chair, Instructor Texas State Technical college Executive Director, Student Affairs Assessment & Robert Aaron Planning Northwestern University Osomiyor Abalu Residence Hall Director Iowa State University Brianna Abate Associate Professor of Communication Prairie State College Marie Abate Professor and Director of Programmatic Assessment West Virginia University ISMAT ABBAS PhD Candidate Montclair State University Noura Abbas Dr. Colorado Technical University Sophia Abbot Graduate Research Assistant George Mason University Associate Professor of English/Learning Outcomes Michelle Abbott Assessment Coordinator Georgia Highlands College Talia Abbott Chalew Dr. Purdue Global Sienna Abdulahad Director Tulane University Fitsum Abebe Instructional Designer and Technology Specialist Doane University Farhana Abedin Assistant Professor California State Polytechnic University Pomona Kristin Abel Professor Valencia College Robert Abel Jr Chief Academic Officer Abraham Lincoln University Leslie Abell Lecturer Faculty CSU Channel Islands Dana Abell‐Huffman Faculty instructor Ivy Tech Annette -

Phaung Daw Oo International University: Pre- College Program

Presentation Phaung Daw Oo International University: Pre- College Program Providing further education for students with leadership abilities 2 Phaung Daw Oo International University: Pre-College Program (PIU-PCP) - Overview The Pre-College Program (PCP) was established in 2012 by two venerable Buddhist monks to provide underprivileged Myanmar high school graduates access to civic education and university preparation. Leading on from Phaung Daw Oo Monastic School, which was established in 1993 to provide free basic education from kindergarten to high school, PCP extends to further educate students of advanced civic education as well as community contribution and leadership. The programme is also designed to help connect graduates to educational opportunities at foreign universities, given that the current capacity of local universities remains somewhat limited and highly regulated. The main aim of PCP is to develop students into engaged community leaders and responsible citizens who will be able to contribute to the democratic development of Myanmar and its community institutions. Child's Dream Foundation 238/3 Wualai Road, T. Haiya, A. Muang, Chiang Mai 50100, Thailand Email: [email protected] • Website: www.childsdream.org • Tel. +66 (0) 53 201 811 • Fax +66 (0) 53 201 812 3 How It Works In each academic year, PCP comprises of a 10-month Academic and Inter-Cultural Studies, followed by a 2-month Service Learning Course. The 10-month course of Academic and Inter-Cultural Studies (Apr – Jan) is instructed primarily in English and introduces subjects from politics to social issues and environment, namely: Politics Philosophy Social Science International Relations, Diplomacy & South East Asia Studies Global Citizenship Psychology Environmental Studies Peace Education The course is intensive with an offer of 6 hours of class on average daily, over 5-day weeks. -

CHAMPAGNATDECEMBER09.Pdf

Champagnat An International Marist Journal of Education and Charism Volume 11 Number 3 December 2009 COMMENT 3 Beginnings John McMahon 8 The Berlin Wall Peter Houlahan 10 Our contributors 12 Launching Lee McKenzie FEATURED ARTICLES 16 Hap and Mishap Frederick McMahon 38 Mary Ward, the Loretos and the 1980s Constance Lewis 74 Australasia’s first Provincial Frederick McMahon RESPONSES AND OpiNION 24 The dance: missionaries now Jeff Crowe REVIEws (BOOKS) 82 The Girl Who Kicked the Hornet’s Nest Madeleine Laming 84 Expert Educators – a Handbook for New Madeleine Laming and Inexperienced Teachers REVIEws (Film) 87 Capitalism: A Love Story Gil Maclean 89 Ponyo; A Christmas Carol; Amelia Hughes- New Moon Lobert REVIEW (TELEVISION) 100 My Place (ABC3) Juliette Hughes DECEMBER 2009 CHAMPAGNAT 1 Champagnat: An International Marist Journal of Education and Charism aims to present information on research, educational practice and policy-making in the field of Champagnat Education and other associated areas in a format that is accessible to both researcher and practitioner, within and beyond the international Marist network. Qualitative and quantitative data, case studies, historical analyses and more theoretical, analytical and philosophical material are welcomed. The journal aims to assist in the human formation and exploration of ideas of those who feel inspired by a charism, its nature and purpose. In this context, charism is seen as a gift to an individual, in our case Marcellin Champagnat, who in turn inspires a movement of people, often internationally, across generations. Such an educational charism encourages people to gather, to share faith, to explore meaning, to display generosity of spirit and to propose a way forward for education, particularly of the less advantaged. -

Needs Assessment of Administrators' School

International Journal of Management and Applied Science, ISSN: 2394-7926 Volume-1, Issue-9, Special Issue Oct.-2015 NEEDS ASSESSMENT OF ADMINISTRATORS’ SCHOOL LEADERSHIP IN MONASTIC SCHOOL, MYANMAR 1VEN. SETTHANANDI, 2SIWAPORN POOPAN 1,2Department of Education, Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities, Mahidol University, Thailand E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] Abstract- The purpose of this study is to identify and analyze the current and expected situation of administrators’ school leadership in monastic schools, Myanmar and to propose suggestion to develop in the future. This study focused on monastic school with modern education system. Two styles of administrators’ school leadership, instructional leadership and transformational leadership are employed as the model of administrators’ school leadership. Modified Priority Needs Index (PNImodified) for needs assessment is employed to get the needs between the current and expected situation with an emphasis on eight components; five components for instructional leadership and three components for transformational leadership. After that, an informal interview method is used to get suggestion for the development in the future. The findings of quantitative part revealed that (1) The most critical needs of instructional school leadership is monitoring and accessing the teaching process and ranks as the first priority, followed by staff development, and creating and developing the school climate, (2) The most critical needs of transformational school leadership was initiation of change with first rank need, followed by the institualization of change and implementation of change. The interview’s result proposes suggestions that the authorities should consider in those needs which quantitative result expressed. Keywords- Needs Assessment, Administrators’ School Leadership, Monastic School I. -

The Monastic Libraries of the Diocese of Winchester During the Late Anglo-Saxon and Norman Periods

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 12-1981 The Monastic Libraries of the Diocese of Winchester during the Late Anglo-Saxon and Norman Periods Steven F. Vincent Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Medieval History Commons, and the Medieval Studies Commons Recommended Citation Vincent, Steven F., "The Monastic Libraries of the Diocese of Winchester during the Late Anglo-Saxon and Norman Periods" (1981). Master's Theses. 1842. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/1842 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE MONASTIC LIBRARIES OF THE DIOCESE OF WINCHESTER DURING THE LATE ANGLO-SAXON AND NORMAN PERIODS by Steven F. Vincent A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Medieval Institute Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan December 1981 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Anyone who works on a project for several years neces sarily finds himself indebted to a great number of people without whose patience and assistance the work would never have been completed. Although it is not possible to thank each individually, there are a few to whom I owe a special debt of gratitude. I am most grateful to Dr. -

The Early Irish Monastic Schools

T H E E A R LY I R I SH M ON A ST I C SC H OO L S ’ A STUDY OF I R ELAND S CONTR IBUTION TO EA RLY M EDI EVAL CULTURE H U G H G R A H A M , M . A . P r r r a ofes s o of E d u c a ti o n . Co llege of S t . Te es . w D U BL I N TALBOT PRESS LIMITED 85 TALBOT STREET 1 923 PREFAC E THE aim of the present study is to give within reasonable limits a critical and fairly complete account of the Irish Monastic Schools which flourish d D e prior to 900 A . The period dealt with covering as it does the one o f sixth , seventh , eighth , and ninth centuries is the most obscure in the history of education . In accordance With established custom writers are wont to bewail the decline of learning consequent on the Fall of the Roman Empire in the fifth century and then they pass on rapidly to the fifteenth Renaissance in the ; a few , however , pau se to glance at the Carolingian Revival of learning in the ninth century and to remark paren thetically that learning was preserved in Ireland and a few isolated places o n the fringe of Roman Civilization , but With some notable exceptions writers as a class have failed to realise that as in other departments of human knowledge there is a continuity in the history of education . The great vi i . -

The Thun-Hohenstein University Reforms 1849–1860

The Thun-Hohenstein University Reforms 1849–1860 Conception – Implementation – Aftermath Edited by Christof Aichner and Brigitte Mazohl VERÖFFENTLICHUNGEN DER KOMMISSION FÜR NEUERE GESCHICHTE ÖSTERREICHS Band 115 Kommission für Neuere Geschichte Österreichs Vorsitzende: em. Univ.-Prof. Dr. Brigitte Mazohl Stellvertretender Vorsitzender: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Reinhard Stauber Mitglieder: Dr. Franz Adlgasser Univ.-Prof. Dr. Peter Becker Univ.-Prof. i. R. Dr. Ernst Bruckmüller Univ.-Prof. Dr. Laurence Cole Univ.-Prof. Dr. Margret Friedrich Univ.-Prof. Dr. Elisabeth Garms-Cornides Univ.-Prof. Dr. Michael Gehler Univ.-Doz. Mag. Dr. Andreas Gottsmann Univ.-Prof. Dr. Margarete Grandner em. Univ.-Prof. Dr. Hanns Haas Univ.-Prof. i. R. Dr. Wolfgang Häusler Univ.-Prof. i. R. Dr. Ernst Hanisch Univ.-Prof. Dr. Gabriele Haug-Moritz Dr. Michael Hochedlinger Univ.-Prof. Dr. Lothar Höbelt Mag. Thomas Just Univ.-Prof. i. R. Dr. Grete Klingenstein em. Univ.-Prof. Dr. Alfred Kohler Univ.-Prof. Dr. Christopher Laferl Gen. Dir. Univ.-Doz. Dr. Wolfgang Maderthaner Dr. Stefan Malfèr Gen. Dir. i. R. H.-Prof. Dr. Lorenz Mikoletzky Dr. Gernot Obersteiner Dr. Hans Petschar em. Univ.-Prof. Dr. Helmut Rumpler Univ.-Prof. Mag. Dr. Martin Scheutz em. Univ.-Prof. Dr. Gerald Stourzh Univ.-Prof. Dr. Arno Strohmeyer Univ.-Prof. i. R. Dr. Arnold Suppan Univ.-Doz. Dr. Werner Telesko Univ.-Prof. Dr. Thomas Winkelbauer Sekretär: Dr. Christof Aichner The Thun-Hohenstein University Reforms 1849–1860 Conception – Implementation – Aftermath Edited by Christof Aichner and Brigitte Mazohl Published with the support from the Austrian Science Fund (FWF): PUB 397-G28 Open access: Except where otherwise noted, this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unported License.