CHAMPAGNATDECEMBER09.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mission Mwia Federation

www.mwia.org.au DECEMBER 2018 BVA The MISSION in the year of JUSTICE MWIA FEDERATION Loreto Family Be the Change International Become One! 2 Contents Welcome to Sustain 3 Provide something 4 6 CONTENTS more than ordinary… Belonging to the global Loreto IBVM This year, as a guest speaker at Message from the Executive Officer 3 network ensures that the friends of Loreto Normanhurst, I witnessed the Mary Ward International Australia overwhelming commitment not only Inspirational Unity 4 are part of 400 years of faith filled to the value of Justice, but to each of tradition. Each day we walk in the the five General Congregation Calls Loreto Family International & MWIA Become One footsteps of those who have gone of the IBVM. before us, on the same journey… The MISSION 6 a journey seeking change. All these young students around Australia are change makers of In the Year of Justice This December edition of Sustain the future. bears witness to the many ways Loreto The Loreto network connections are Project Update: Vietnam 16 women and men walk in the footsteps long standing, beginning with our Responding to needs… of Mary Ward and Saint Ignatius, school connections and continuing in a making a difference of their own. variety of relationships. In this edition Loreto Federation 2018 18 The Mission and Feast Days of our we recognise the efforts of former “Be the change” Australian Loreto schools are featured pupils who are loyal supporters of the in an acknowledgement of the work of our Loreto Sisters. We are 16 Project Update: NSW, Australia 22 extraordinary efforts of all the students. -

Mary Ward's Women

Archival Display Celebrating Loreto’s 400 Years Presented at Loreto College Ballarat November 2009 Mary Ward’s Women 400 Years of the Institute of the Blessed Virgin Mary In 2009-2011 the Loreto Sisters celebrate 400 years since Mary Ward began her work. They rejoice in and honour the vision, courage and commitment of their founder and her legacy of sisters and schools on every continent, hundreds of thousands of students past and present, countless volunteers, colleagues and friends across the globe; and social justice and education missions that serve the vulnerable, disadvantaged and voiceless around the world. Her followers today work in every continent and try to live by her ideals, promoting the gifts of women in "freedom, justice and sincerity", in a way of life that places emphasis on reflection and action, to serve the gospel "wherever the need is greatest". Mary Ward (1585-1645), was an Englishwoman from Yorkshire who founded the Loreto Sisters. She was a progressive and visionary woman of her time who believed “women in time to come would do much”. She believed that women and men were of equal intellect - a brave assertion at the time - and that they should be educated equally. Mary Ward pioneered a new form of religious life for women (without the constraints of the traditional cloister) – a female version of the Jesuits. Together with her followers she set up schools across England and Europe. By remaining faithful to her insights, she was condemned, those who joined her were disbanded and the Institute suppressed. Despite persecution and scandals about her way of religious life her vision and values live on today – in Australia and around the world. -

What's Happening

Casa Loreto July 2020 What’s happening An update INSIDE THIS ISSUE Grounded! Locked Down! Cocooned: Maybe GROUNDED, LOCKED DOWN, COCOONED! We Were Caterpillars……………………………...1 MAYBE WE WERE CATERPILLARS Six months in Rome…………………………….….3 Presentation Manor and Covid………………..4 Covid 19—Prevention and sensitization…….5 A voice from Ghana…………………………….....6 Keep social distance… to encounter………...7 Our graduates have come back to help……..8 A time of patient waiting………..……………..10 Another frontline worker……………………....11 Excerpts from Manila…………………………….12 Helping Kibera families……………………......13 Covid prevention in a small island………..…15 Great gratitude to Cecilia O’Dwyer…….…...16 Lockdown in Llandudno……………...…….....17 My experience in Peru…………………………...19 My experience in the border………………....20 A nurse’s call…………………………………………21 An invitation to prayer……………………....…22 My memories with God, always in the way……………………………………………………..22 A suitable time to travel and explore new landscapes…………………………………………...25 Congratulations to Anita Braganza…………26 Be merry and doubt not your Master……...27 Our mid-term break vaulted us around the world. Still we were Darjeeling Mary Ward Social Centre…......28 into the privileged but arduous naïvely making our 2020 meet- New residence in Entally……………………….29 work of tallying the leaning for ing schedule and finalizing Sisters turning 100 ……………………………….29 union in late January 2020. By flight bookings to the next visit- Candidates, Novices and Temporary Pro- then, we know now that Covid ation, consultations, ELM, GC fessed……………………………………………..…..30 19 was rapidly making its way prep and Union. A new joint CJ IBVM office in Rome ……..41 Thank you for the care…………..………….….41 The death toll and illness on over- story of the paschal mystery. -

Monastic Schools in Myanmar – a Baseline Study

2014 – Monastic schools in Myanmar a baseline study Burnet Institute Myanmar & Monastic Education Development Group February 2014 MEC Baseline Report of Monastic Schools, 2014 February 2014 Lead authors are Hilary Veale from the Burnet Institute, Melbourne and Dr Poe Poe Aung from the Burnet Institute, Myanmar, with contributions from Professor Margaret Hellard, Dr Karl Dorning, Dr Freya Fowkes, Damien McCarthy, Paul Agius, Khin Hnin Oo, Than Htet Soe, and Yadanar Khin Khin Kyaw. Acknowledgements The Burnet Institute and the Monastic Education Development Group would like to thank Phaung Daw Oo School for their collaboration in this baseline assessment and for providing excellent data collection staff who worked tirelessly in the field, and completed data entry, checking and cleaning. We also wish to acknowledge and give thanks to all the principals, staff and students of monastic schools who generously gave up their time and shared their knowledge with us. Their kind hospitality was also much appreciated by our data collection teams. This survey would not have been possible without their participation and we hope that the findings from this survey will benefit them in the future, through the MEC project and beyond. This baseline study was supported through the Myanmar Education Consortium with funds from the Australian and UK Governments. This report should be cited as Burnet Institute and Monastic Education Development Group (2014), Monastic schools in Myanmar – a baseline study. Cover photograph: Monastic school classroom (Than Htet -

Situation Analysis of the Monastic Education System in Myanmar Final Report July 2015

Situation Analysis of the Monastic Education System in Myanmar Final Report July 2015 Daw Ohnmar Tin and Miss Emily Stenning Inside front cover Situation Analysis of the Monastic Education System in Myanmar Final Report July 2015 Daw Ohnmar Tin and Miss Emily Stenning Front cover images: Kanthaya Monastery (left), Shwe Yin Aye Monastery (right) Credit: Burnet Institute and MEDG Text and image copyright: Myanmar Education Consortium (MEC) 2016 Graphic design by Katherine Gibney | www.accurateyak.carbonmade.com Ohnmar Tin has worked as teacher, social welfare officer, child protection officer, educator, trainer and module writer for competency-based teacher training program for primary level untrained teachers in non-government sector and is now a freelance consultant. Her services include teacher training for untrained primary school teachers in non-government sector with various organisations such as Metta Development Foundation, Shalom Foundation, Pestalozzi Children Foundation and early grade reading assessment with the Departments of Basic Education and the World Bank; and kindergarten curriculum development with the Departments of Basic Education. She has been involved in various needs analysis, and participatory rapid appraisal research in various part of Myanmar. She has worked on end of cycle project evaluation exercises with organisations including World Vision, Save the Children, as well as local Kachin, Karen, Ar Khar, Larhu, Wa Baptist Conventions. Contact: [email protected] Emily Stenning is an independent education consultant who has lived and worked in Myanmar since 2013. She has 10 years experience of advising and delivering education policies and programmes. She has experience in a range of educational areas from teacher training through to innovative financing strategies, but her specialist area is looking at how to address the persistent barriers denying children access to quality education. -

Laudato Si’- a Way of Life

Laudato Si’- A way of life Mary Ward Sisters South Asia Celebrate The 5th Anniversary of Laudato Si' Week from 16-24 May 2020. “Let’s take care of creation, a gift of our creater God. Let’s celebrate Laudato Si’ Week together.” MERGER MILESTONE: A RATIONALE We are humbled at this opportunity bestowed by the Almighty. Truly, His ways are beyond our comprehension. These last few days have taught us that 'With God, all things are possible.' This is veritably, a major Merger Milestone, that has brought together students, teachers and Sisters of both the congregations of Mary Ward. What better way than to celebrate Laudato Si Week, than to do so in fellowship with each other and the rest of the creation. The celebration of the 5th Anniversary of the Laudato Si Week could not have been more apt this year, despite all the impediments and inexplicable phenomena, natural and otherwise. The Pope's passionate call must be paid heed to, so that we set a purpose to the pangs of protecting this world. These uncertain times, with cyclones, frequent earthquakes, floods and the current pandemic, have only given an impetus to the efforts in this collaborative effort to quell the ecological crises. This was possible only by merging and mirroring the myriad of ideas for a sustainable future. This week was an insightful and introspective journey for all the participants, the JPIC National and Zonal coordinators, both congregations of Mary Ward and Tarumitra. We have learnt that each one of us has a key role to play, like cogs in a wheel, in the future of this world, and to maintain its integrity. -

Self-Knowledge in the Theology of Bernard Of

MY BELOVED IS MINE AND I AM HIS: SELF-KNOWLEDGE IN THE THEOLOGY OF BERNARD OF CLAIRVAUX A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Notre Dame in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by James U. DeFrancis, Jr. Ann W. Astell, Director Graduate Program in Theology Notre Dame, Indiana July 2012 © Copyright 2012 James U. DeFrancis, Jr. MY BELOVED IS MINE AND I AM HIS: SELF-KNOWLEDGE IN THE THEOLOGY OF BERNARD OF CLAIRVAUX Abstract by James U. DeFrancis, Jr. This dissertation examines the various forms and roles self-knowledge assumes in Bernard of Clairvaux’s overarching vision of the spiritual life. Previous scholarship on Bernard’s doctrine of self-knowledge has correctly emphasized the significance he attaches to humbling self-knowledge, or the soul’s honest self-recognition as a disfigured image of God, in the soul’s first conversion and the initial stages of its return to God. A certain scholarly preoccupation with this aspect of the abbot’s thought has, however, somewhat obscured the full breadth of Bernard’s teaching on self-knowledge and the diverse forms and roles it assumes across the various phases of the soul’s spiritual life, including those which both proceed and follow its first conversion. Prior to its first conversion, Bernard believes, the soul suffers not only from self- ignorance, but also from a self-deception, a false self-knowledge born of pride, by which it imagines itself superior to others and therefore not in need of conversion or healing. It is precisely because he recognizes the seductive power of this self-deception that Bernard so frequently insists upon the soul’s humbling recognition of its own sad disfigurement as James U. -

A Comparative Study on Students' Satisfaction

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Assumption Journals 271 A COMPARATIVE STUDY ON STUDENTS’ SATISFACTION BETWEEN NAUNG TAUNG MONASTIC HIGH SCHOOL AND KYAUK TA LONE PUBLIC HIGH SCHOOL IN SOUTHERN SHAN STATE, MYANMAR Ven. Pandita Dhaja Lankara1 YanYe2 Abstract: The purpose of this study was to compare the students’ satisfaction towards the school instruction, course, grading, test, guidance, rules, library, and assistance between Naung Taung monastic high school and Kyauk Ta Lone public high school in southern Shan state, Myanmar. The collected data were analyzed by using the descriptive statistics including Frequency, Percentage, Standard deviation Mean; and Inferential Independent Samples t-test (Two-tailed). The study found that the students’ satisfaction at both schools were high. Thus, the research also found that in general there was no significant difference of students’ satisfaction between Naung Taung monastic high school and Kyauk Ta Lone public high school in southern Shan state, Myanmar. However, significant difference of students’ satisfaction towards course, grading, test, rules, and assistance were also founded in two schools. Keywords: Students’ Satisfaction, Myanmar, Monastic High School Introduction Since the earliest days, Myanmar has highly regarded education as their property of life. Because of this opinion, Myanmar people, from the past to present, firmly hold the motto “no one can steal or take away the golden pot of wisdom from those who have educated.” Traditionally, Myanmar people have strongly relied on monastic education since the time of the Myanmar kings, and they also had significantly at that time (Han Tin, 2000). -

Cistercian and Monastic Studies 2017 C O N F E R E N C E

cistercian and monastic studies 2017 C O N F E R E N C E Western Michigan University Program and Schedule of Events In conjunction with the 52nd International Congress on Medieval Studies May 11–14, 2017 Thursday, May 11 | Lee Honors College Lounge Friday, May 12 | Lee Honors College Lounge 10:00 a.m. 10:00 a.m. Monks and the World: Political and Economic Activities Monastic Lives Presider: Jean Truax, Independent Scholar Presider: Martha Krieg, Independent Scholar St. Bernard of Clairvaux and the Crusades The Wrong Side of History: Thomas Becket and Aelred of Rievaulx Ryszard Gron, Archdiocese of Chicago Jean A. Truax, Independent Scholar Saint George’s Abbey in Gratteri - Ninian and the Rod of Aaron The First Cistercian Settlement in the Kingdom of Sicily? Chad Turner, Saint Joseph’s College Francesco Capitummino, Independent Scholar Exemplum as History: The Worlds of a Cistercian Nun Katherine Richman, Laboure College 1:30 p.m. Spirituality in Monastic Life 1:30 p.m. Presider: Hugh Feiss, OSB Dubious Sources in Monastic History “The Word Runs Swiftly”: Presider: Anne Lester, University of Colorado-Boulder The Symbolism of “Running” in Bernard and William The First Life of Bernard: Can we trust it? Isaac Slater, OCSO Brian Patrick McGuire, Independent Scholar Early Symptoms of Humanism in Bernard’s de Deligendo Deo Popular Perceptions of Cistercians vs. Trappists in late 19th Century Austria Luke Anderson, O. Cist, St. Mary’s Monastery Alcuin Schachenmayr, O. Cist, Pontifical Athanaeum Benedict XVI. The “Paradise of Inner Pleasure”: Heiligenkreuz The “Monastery” in Medieval Monastic Spirituality Mortifera salutacio: Herbert of Torres’ Version of the Devil’s Letter Greg Peters, Biola University Stefano Mula, Middlebury College 3:30 p.m. -

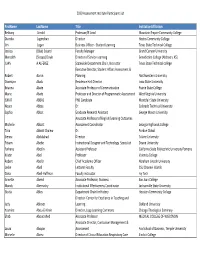

2020 Assessment Institute Participant List Firstname Lastname Title

2020 Assessment Institute Participant List FirstName LastName Title InstitutionAffiliation Bethany Arnold Professor/IE Lead Mountain Empire Community College Diandra Jugmohan Director Hostos Community College Jim Logan Business Officer ‐ Student Learning Texas State Technical College Jessica (Blair) Soland Faculty Manager Grand Canyon University Meredith (Stoops) Doyle Director of Service‐Learning Benedictine College (Atchison, KS) JUAN A ALFEREZ Statewide Department Chair, Instructor Texas State Technical college Executive Director, Student Affairs Assessment & Robert Aaron Planning Northwestern University Osomiyor Abalu Residence Hall Director Iowa State University Brianna Abate Associate Professor of Communication Prairie State College Marie Abate Professor and Director of Programmatic Assessment West Virginia University ISMAT ABBAS PhD Candidate Montclair State University Noura Abbas Dr. Colorado Technical University Sophia Abbot Graduate Research Assistant George Mason University Associate Professor of English/Learning Outcomes Michelle Abbott Assessment Coordinator Georgia Highlands College Talia Abbott Chalew Dr. Purdue Global Sienna Abdulahad Director Tulane University Fitsum Abebe Instructional Designer and Technology Specialist Doane University Farhana Abedin Assistant Professor California State Polytechnic University Pomona Kristin Abel Professor Valencia College Robert Abel Jr Chief Academic Officer Abraham Lincoln University Leslie Abell Lecturer Faculty CSU Channel Islands Dana Abell‐Huffman Faculty instructor Ivy Tech Annette -

Phaung Daw Oo International University: Pre- College Program

Presentation Phaung Daw Oo International University: Pre- College Program Providing further education for students with leadership abilities 2 Phaung Daw Oo International University: Pre-College Program (PIU-PCP) - Overview The Pre-College Program (PCP) was established in 2012 by two venerable Buddhist monks to provide underprivileged Myanmar high school graduates access to civic education and university preparation. Leading on from Phaung Daw Oo Monastic School, which was established in 1993 to provide free basic education from kindergarten to high school, PCP extends to further educate students of advanced civic education as well as community contribution and leadership. The programme is also designed to help connect graduates to educational opportunities at foreign universities, given that the current capacity of local universities remains somewhat limited and highly regulated. The main aim of PCP is to develop students into engaged community leaders and responsible citizens who will be able to contribute to the democratic development of Myanmar and its community institutions. Child's Dream Foundation 238/3 Wualai Road, T. Haiya, A. Muang, Chiang Mai 50100, Thailand Email: [email protected] • Website: www.childsdream.org • Tel. +66 (0) 53 201 811 • Fax +66 (0) 53 201 812 3 How It Works In each academic year, PCP comprises of a 10-month Academic and Inter-Cultural Studies, followed by a 2-month Service Learning Course. The 10-month course of Academic and Inter-Cultural Studies (Apr – Jan) is instructed primarily in English and introduces subjects from politics to social issues and environment, namely: Politics Philosophy Social Science International Relations, Diplomacy & South East Asia Studies Global Citizenship Psychology Environmental Studies Peace Education The course is intensive with an offer of 6 hours of class on average daily, over 5-day weeks. -

Needs Assessment of Administrators' School

International Journal of Management and Applied Science, ISSN: 2394-7926 Volume-1, Issue-9, Special Issue Oct.-2015 NEEDS ASSESSMENT OF ADMINISTRATORS’ SCHOOL LEADERSHIP IN MONASTIC SCHOOL, MYANMAR 1VEN. SETTHANANDI, 2SIWAPORN POOPAN 1,2Department of Education, Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities, Mahidol University, Thailand E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] Abstract- The purpose of this study is to identify and analyze the current and expected situation of administrators’ school leadership in monastic schools, Myanmar and to propose suggestion to develop in the future. This study focused on monastic school with modern education system. Two styles of administrators’ school leadership, instructional leadership and transformational leadership are employed as the model of administrators’ school leadership. Modified Priority Needs Index (PNImodified) for needs assessment is employed to get the needs between the current and expected situation with an emphasis on eight components; five components for instructional leadership and three components for transformational leadership. After that, an informal interview method is used to get suggestion for the development in the future. The findings of quantitative part revealed that (1) The most critical needs of instructional school leadership is monitoring and accessing the teaching process and ranks as the first priority, followed by staff development, and creating and developing the school climate, (2) The most critical needs of transformational school leadership was initiation of change with first rank need, followed by the institualization of change and implementation of change. The interview’s result proposes suggestions that the authorities should consider in those needs which quantitative result expressed. Keywords- Needs Assessment, Administrators’ School Leadership, Monastic School I.