Two Markets, Two Resources: Documenting China's Engagement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

United States Securities and Exchange Commission Washington, D.C

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20549 FORM SD SPECIALIZED DISCLOSURE REPORT RIBBON COMMUNICATIONS INC. (Exact Name of Registrant as Specified in its Charter) DELAWARE 001-38267 82-1669692 (State or Other Jurisdiction (Commission File Number) (IRS Employer of Incorporation) Identification No.) 4 TECHNOLOGY PARK DRIVE, WESTFORD, MASSACHUSETTS 01886 (Address of Principal Executive Offices) (Zip Code) Justin K. Ferguson, Executive Vice President, General Counsel and Secretary (978) 614-8100 (Name and telephone number, including area code, of the person to contact in connection with this report) Check the appropriate box to indicate the rule pursuant to which this form is being filed, and provide the period to which the information in this form applies: ☒ Rule 13p-1 under the Securities Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.13p-1) for the reporting period from January 1 to December 31, 2019. Section 1 — Conflict Minerals Disclosure Item 1.01. Conflict Minerals Disclosure and Report Ribbon Communications Inc. (the “Company” or “Ribbon”) has determined that some of the products that it manufactured or contracted to manufacture through the end of reporting year 2019 (“Ribbon Products”), include gold, columbite-tantalite (coltan), cassiterite and wolframite, including their derivatives, tantalum, tin and tungsten (collectively, “Conflict Minerals”). The Company has further determined that these Conflict Minerals are necessary to the functionality or production of the Ribbon Products. The Company conducted a Reasonable Country of Origin Inquiry (“RCOI”) to determine whether any of the Conflict Minerals in the Ribbon Products originated in the Democratic Republic of the Congo or an adjoining country (“Covered Country”) and whether the Conflict Minerals are from recycled or scrap sources. -

The Mineral Industry of China in 2016

2016 Minerals Yearbook CHINA [ADVANCE RELEASE] U.S. Department of the Interior December 2018 U.S. Geological Survey The Mineral Industry of China By Sean Xun In China, unprecedented economic growth since the late of the country’s total nonagricultural employment. In 2016, 20th century had resulted in large increases in the country’s the total investment in fixed assets (excluding that by rural production of and demand for mineral commodities. These households; see reference at the end of the paragraph for a changes were dominating factors in the development of the detailed definition) was $8.78 trillion, of which $2.72 trillion global mineral industry during the past two decades. In more was invested in the manufacturing sector and $149 billion was recent years, owing to the country’s economic slowdown invested in the mining sector (National Bureau of Statistics of and to stricter environmental regulations in place by the China, 2017b, sec. 3–1, 3–3, 3–6, 4–5, 10–6). Government since late 2012, the mineral industry in China had In 2016, the foreign direct investment (FDI) actually used faced some challenges, such as underutilization of production in China was $126 billion, which was the same as in 2015. capacity, slow demand growth, and low profitability. To In 2016, about 0.08% of the FDI was directed to the mining address these challenges, the Government had implemented sector compared with 0.2% in 2015, and 27% was directed to policies of capacity control (to restrict the addition of new the manufacturing sector compared with 31% in 2015. -

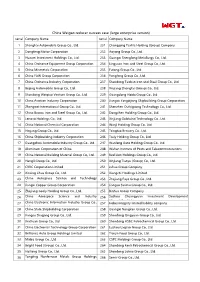

China Weigao Reducer Success Case (Large Enterprise Version) Serial Company Name Serial Company Name

China Weigao reducer success case (large enterprise version) serial Company Name serial Company Name 1 Shanghai Automobile Group Co., Ltd. 231 Chongqing Textile Holding (Group) Company 2 Dongfeng Motor Corporation 232 Aoyang Group Co., Ltd. 3 Huawei Investment Holdings Co., Ltd. 233 Guangxi Shenglong Metallurgy Co., Ltd. 4 China Ordnance Equipment Group Corporation 234 Lingyuan Iron and Steel Group Co., Ltd. 5 China Minmetals Corporation 235 Futong Group Co., Ltd. 6 China FAW Group Corporation 236 Yongfeng Group Co., Ltd. 7 China Ordnance Industry Corporation 237 Shandong Taishan Iron and Steel Group Co., Ltd. 8 Beijing Automobile Group Co., Ltd. 238 Xinjiang Zhongtai (Group) Co., Ltd. 9 Shandong Weiqiao Venture Group Co., Ltd. 239 Guangdong Haida Group Co., Ltd. 10 China Aviation Industry Corporation 240 Jiangsu Yangzijiang Shipbuilding Group Corporation 11 Zhengwei International Group Co., Ltd. 241 Shenzhen Oufeiguang Technology Co., Ltd. 12 China Baowu Iron and Steel Group Co., Ltd. 242 Dongchen Holding Group Co., Ltd. 13 Lenovo Holdings Co., Ltd. 243 Xinjiang Goldwind Technology Co., Ltd. 14 China National Chemical Corporation 244 Wanji Holding Group Co., Ltd. 15 Hegang Group Co., Ltd. 245 Tsingtao Brewery Co., Ltd. 16 China Shipbuilding Industry Corporation 246 Tasly Holding Group Co., Ltd. 17 Guangzhou Automobile Industry Group Co., Ltd. 247 Wanfeng Auto Holding Group Co., Ltd. 18 Aluminum Corporation of China 248 Wuhan Institute of Posts and Telecommunications 19 China National Building Material Group Co., Ltd. 249 Red Lion Holdings Group Co., Ltd. 20 Hengli Group Co., Ltd. 250 Xinjiang Tianye (Group) Co., Ltd. 21 CRRC Corporation Limited 251 Juhua Group Company 22 Xinxing Jihua Group Co., Ltd. -

China Molybdenum Co (3993 HK)

China Thursday , 25 January 2018 INITIATE COVERAGE BUY China Molybdenum Co (3993 HK) An Emerging Global Mining Giant; Riding On Cobalt And Copper Momentum Share Price HK$5.97 China Molybdenum Co has evolved into one of the world’s leading mining Target Price HK$6.78 companies with diversified resources exposure. We forecast 40%+ EPS CAGR in Upside +13.0% 2017-20, given: a) our positive view on copper and cobalt in the medium to long term, b) the likelihood of tungsten and molybdenum’s high-margin advantage COMPANY DESCRIPTION persisting, and c) the niobium and phosphate segments providing stable cash flows. Initiate coverage with BUY and target price of HK$6.78 on DCF life-of-mine valuation. China Molybdenum Co is a mineral mining and exploration company engaged in the Copper: Positive outlook in the medium term on solid fundamentals. From a global mining and processing of molybdenum, perspective, we favour copper among base metals for the next 2-3 years given: a) supply tungsten, copper, cobalt, niobium and constraint due to under-investment, mines’ grade declines and elevated mine strike risks; phosphate minerals. and b) demand supported by traditional consumption and rising adoption of electric vehicles (EV). We expect LME copper prices to stay high at US$7,000-7,200/tonne in STOCK DATA 2018-20. China Molybdenum Co (CMOC) owns two world-class copper mines Tenke GICS sector Materials Fungurume Mining S.A (Tenke) and Northparkes Mine (Northparkes) with a combined Bloomberg ticker: 3993 HK mined copper production of 240k-260k tpa. Shares issued (m): 3,933.5 Market cap (HK$m): 200,112.6 Cobalt: Riding on EV momentum. -

Interim Report 2013

Jinchuan Group International Resources Co. Ltd (Incorporated in the Cayman Islands with limited liability) (Stock Code:2362) CONTENTS Pages UNAUDITED INTERIM FINANCIAL REPORT Condensed Consolidated: Statement of Profit or Loss and Other Comprehensive Income 2 Statement of Financial Position 3 Statement of Changes in Equity 5 Statement of Cash Flows 6 Notes to the Condensed Consolidated Financial Statements 7 Management Discussion and Analysis 19 Disclosure of Interests 24 Share Option Scheme 26 Corporate Governance Information 26 Jinchuan Group International Resources Co. Ltd CONDENSED CONSOLIDATED STATEMENT OF PROFIT OR LOSS AND OTHER COMPREHENSIVE INCOME For the six months ended 30 June 2013 Six months ended 30.6.2013 30.6.2012 Notes HK$’000 HK$’000 (unaudited) (restated and unaudited) CONTINUING OPERATION Revenue 1,147,451 165,934 Cost of sales (1,113,566) (164,014) Gross profit 33,885 1,920 Other income 882 5,559 Other gains and losses 5 14,320 (2,760) Selling and distribution costs (1,362) (1,468) Administrative expenses (7,471) (6,582) Other expenses (15,377) – Finance costs (6,917) (1) Profit (loss) before taxation 6 17,960 (3,332) Taxation 7 (4,257) – Profit (loss) for the period from continuing operation 13,703 (3,332) DISCONTINUED OPERATIONS Profit (loss) for the period from discontinued operations 8 21,887 (2,232) Profit (loss) for the period 35,590 (5,564) Other comprehensive income (expense) Items that may be reclassified subsequently to profit or loss: Exchange difference arising on translation of foreign operations (79) -

Afrikas Ekonomi, Mineralråvaror Och Kina

Afrikas ekonomi, mineralråvaror och Kina Program • Afrika - bakgrund • Gruvindustrin i världen • Gruvindustrin i Afrika • Kina i Afrika Magnus Ericsson / 孟瑞松 Råvarugruppen, Luleå Tekniska Universitet Afrika - bakgrund Manganese drawing: Kaianders Sempler. Africa – a giant 20 % av jordytan Africa – key figures Area: 30 370 000 km² 20 % Population: 1,216 miljarder World 7,466 17 % GDP: 2141 billion USD global 75848 2.8% GNI per capita: Sub-saharan Africa 1515 USD World 10368 Sweden 54480 Africa – growing faster 1 Fastest growing countries Country 2007-2016 1 Ethiopia 10.22 2 China 9.00 3 Myanmar 8.56 4 Uzbekistan 8.36 5 Rwanda 7.62 6 Afghanistan 7.40 7 India 7.35 8 Ghana 6.84 9 Tanzania 6.70 10 Mozambique 6.67 11 Angola 6.59 12 Cambodia 6.58 13 Zambia 6.48 14 Iraq 6.39 15 Congo, Dem. Rep. 6.35 Sub-Saharan Africa 4.26 World 2.49 people million 10 than less with countries Excludes 10 12 14 Africa -4 -2 6 8 0 2 4 1995 1996 1997 1998 – 1999 growing 2 fastergrowing 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 high income) high (excluding Africa Sub-Saharan World Global gruvindustri Vanadium drawing: Kaianders Sempler. Mining in the world Source: Raw Materials Data Mining - a historical perspective 70 Europe 60 USA 50 40 China 30 USSR/CIS 20 Australia/Canada % of world mining 10 6RR 0 Other Source: Sames, Raw Materials Data Minerals produced Value 2014 Commodity Mined Unit Price Unit (USD billon) Aggregates 48 000 Mt - - - Coal 8085 Mt 80 USD/t 647 Iron ore 3415 Mt 71 USD/t 146 Gold 3.1 kt 1266 USD/oz 123 -

Allot Communications Ltd

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 __________________ Form SD __________________ Specialized Disclosure Report Allot Communications Ltd. Israel 001-33129 N/A (State or other jurisdiction of incorporation) (Commission File Number) (I.R.S. Employer Identification No.) 22 Hanagar Street Neve Ne’eman Industrial Zone B Hod-Hasharon 4501317 Israel Rael Kolevsohn General Counsel Tel +972-9-7619200 Check the appropriate box to indicate the rule pursuant to which this form is being filed, and provide the period to which the information in this form applies: ☒ Rule 13p-1 under the Securities Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.13p-1) for the reporting period from January 1 to December 31, 2015. SECTION 1 – CONFLICT MINERALS DISCLOSURE Item 1.01 Conflict Minerals Disclosure and Report Introduction This Specialized Disclosure Form (“Form SD”) of Allot Communications Ltd. (the “Company,” “we,” or “us”) is filed pursuant to Rule 13p-1 (the “Rule”) promulgated under the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, as amended (the “Exchange Act”), for the reporting period from January 1, 2015 to December 31, 2015. The Rule requires disclosure of certain information when a company manufactures or contracts to manufacture products for which the minerals specified in the Rule are necessary to the functionality or production of those products. The specified minerals are gold, columbite-tantalite (coltan), cassiterite and wolframite, including their derivatives, which are limited to tantalum, tin and tungsten (collectively, the “Conflict Minerals”), -

Than a Pretty Color: the Renaissance of the Cobalt Industry

United States International Trade Commission Journal of International Commerce and Economics February 2019 More Than a Pretty Color: The Renaissance of the Cobalt Industry Samantha DeCarlo and Daniel Matthews Abstract Demand for cobalt—a major input in the production of lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) used in electric vehicles (EVs)—is growing due to recent technological advancements and government policies designed to promote the use of EVs. This has led major automakers, battery manufacturers, personal electronic device companies, and their suppliers to attempt to secure stable supplies and develop new sources of cobalt throughout the world. Moreover, the rising demand for cobalt has led to global supply constraints, higher prices, and renewed drive in battery materials research for potential substitutes for mined cobalt. Keywords: Cobalt, lithium-ion batteries, supply, chemical, metal, superalloy, China, Democratic Republic of Congo, DRC Suggested citation: DeCarlo, Samantha, and Daniel Matthews. “More Than a Pretty Color- The Renaissance of the Cobalt Industry.” Journal of International Commerce and Economics. February 2019. http://www.usitc.gov/journals. This article is the result of the ongoing professional research of USITC staff and is solely meant to represent the opinions and professional research of its authors. It is not meant to represent in any way the view of the U.S. International Trade Commission, any of its individual Commissioners, or the United States Government. Please direct all correspondence to Samantha DeCarlo and Daniel Matthews, Office of Industries, U.S. International Trade Commission, 500 E Street SW, Washington, DC 20436, or by email to [email protected] and [email protected]. -

Annual Report 2010

2010 年報 ANNUAL REPORT 2010 金川集團國際資源有限公司 Jinchuan Group International Resources Co. Ltd (前稱澳門投資控股有限公司*) (Formerly known as Macau Investment Holdings Limited) (於開曼群島註冊成立之有限公司) (Incorporated in the Cayman Islands with limited liability) *僅供識別 (股份代號:2362) (Stock Code: 2362) CONTENTS 2 Corporate Information 3 Chairman’s Statement 5 Management Discussion and Analysis 10 Corporate Governance Report 15 Biographical Details of Directors and Senior Management 19 Report of the Directors 26 Independent Auditors’ Report 28 Consolidated Statement of Comprehensive Income 30 Consolidated Statement of Financial Position 32 Statement of Financial Position 33 Consolidated Statement of Changes in Equity 35 Consolidated Statement of Cash Flows 37 Notes to Financial Statements 116 Five-Year Financial Summary CORPORATE INFORMATION BOARD OF DIRECTORS REGISTERED OFFICE ADDRESS Executive Directors P.O. Box 309 Mr. Yang Zhiqiang (Chairman of the Board) Ugland House Mr. Zhang Sanlin Grand Cayman KY1-1104 Mr. Zhang Zhong Cayman Islands Ms. Deng Wen Ms. Maria Majoire Lo HEAD OFFICE AND PRINCIPAL PLACE OF BUSINESS IN HONG KONG Non-executive Directors Suite 1203B, 12/F Mr. Gao Tianpeng Tower 1 Mr. Qiao Fugui Admiralty Centre Ms. Zhou Xiaoyin 18 Harcourt Road Hong Kong Independent Non-executive Directors Mr. Gao Dezhu AUDITORS Mr. Wu Chi Keung Ernst & Young Mr. Yen Yuen Ho, Tony Certified Public Accountants COMPANY SECRETARY PRINCIPAL SHARE REGISTRAR AND TRANSFER Mr. Wong Tak Chuen OFFICE Butterfield Bank (Cayman) Limited AUDIT COMMITTEE Mr. Gao Dezhu (Chairman) HONG KONG BRANCH SHARE REGISTRAR Mr. Wu Chi Keung AND TRANSFER OFFICE Mr. Yen Yuen Ho, Tony Hong Kong Registrars Limited REMUNERATION COMMITTEE WEBSITE Mr. Zhang Sanlin (Chairman) www.jinchuan-intl.com Mr. -

Jinchuan International (Stock Code: 2362) Announces Proposed to Sell

For more information, please contact JOVIAN Financial Communications Ltd Angel Yeung Tel:(852) 2581 0168 Fax:(852) 2854 2012 Email:[email protected] 【For Immediate Release】 Jinchuan International (Stock Code: 2362) Announces Proposed to Sell Aggregate Amount of Over Billions USD Mineral Products to its Parent Company Jinchuan Group Accomplished to Making First Move to Tap into Mineral Resources Industry (Hong Kong, 24 July 2011) ‐‐‐‐‐‐ Jinchuan Group International Resources Co. Ltd (“Jinchuan International” or “the Company”) (Stock Code: 2362) announced that on 18 July 2011 the Company entered into an agreement for trading of mineral products with Jinchuan Group Limited (“Jinchuan Group”) to kick off overseas mining business. Pursuant to the agreement, the Company proposed to sell mineral products worth billions of US dollars to its parent company Jinchuan Group which owns 60.5% equity interest of the Company in forecoming three years, of which the estimate sales caps are approximately US$0.3 billion (approximately HK$2.3 billion), approximately US$1.2 billion (approximately HK$9.3 billion) and approximately US$2 billion (approximately HK$15.6 billion) for the years ended 31 December 2011, 2012 and 2013 respectively. Pursuant to the agreement, the selling prices of the mineral products are determined by reference to the prices of copper, nickel and other relevant metals as announced by the London Metal Exchange and London Bullion Market Association and after making certain adjustments taking into account various factors including, among other things, the treatment and refinery charges, bank financing and related charges, foreign exchange differences and the Company’s reasonable profit margin (on top of the aforementioned costs). -

DIGITAL ECONOMY GROWTH and MINERAL RESOURCES Implications for Developing Countries

DIGITAL ECONOMY GROWTH AND MINERAL RESOURCES Implications for Developing Countries No16 UNCTAD, DIVISION ON TECHNOLOGY AND LOGISTICS SCIENCE, TECHNOLOGY AND ICT BRANCH ICT POLICY SECTION TECHNICAL NOTE NO16 UNEDITED TN/UNCTAD/ICT4D/16 DECEMBER 2020 Digital economy growth and mineral resources: 1 implications for developing countries Abstract: This technical note examines the link between growing digitalization of the world economy and the demand for various elements. It feeds into the overall research work of the UNCTAD E- commerce and Digital Economy (ECDE) work programme. The study focuses on the following issues in view of the growing use of digital technologies: What metals/minerals will be more demanded as a result?; What changes in demand can be expected compared with today's situation?; Which mineral-rich developing countries are likely to be most affected by the growth in demand of different metals and minerals?; Which are the main actors (including possibly new actors such as digital companies) involved in the extraction, smelting and refining of these minerals and metals?; and How recyclable will these "new" metals be and to what extent may they be adding to the problem of "e-waste"? Based primarily on desk top research, complemented by a few interviews with representatives from industry and academia, the study deals primarily with the functional parts of computers and other devices, which are at the core of the digital economy. Demands for raw materials from the structural parts of the devices and the networks necessary as well as their energy supply and the consequences of the transition to a fossil free world are not covered. -

New Concentrate Sales Agreement for Savannah

News Release 29 June 2018 New Concentrate Sales Agreement for Savannah Panoramic Resources Limited (“Panoramic” or “Company”) is delighted to announce that Sino Nickel Pty Ltd (“Sino Nickel”), Jinchuan Group Co., Ltd (“Jinchuan”) and Savannah Nickel Mines Pty Ltd (a wholly owned subsidiary of Panoramic) have executed a new four-year Concentrate Sales Agreement, which covers 100% of the concentrate that may be produced from the Savannah Nickel-Copper-Cobalt Project (the “Project”). Details of the New Concentrate Offtake Savannah Nickel Mines Pty Ltd has executed a new Concentrate Sales Agreement (“Agreement”) with Sino Nickel (a joint venture company owned 60% by Jinchuan and 40% by Sino Mining International Limited). This new Agreement replaces the Extended Concentrate Sales Agreement (dated 26 March 2010), which was due to expire on 31 March 2020. The terms of the new Agreement will be applicable from the first shipment of concentrate from the recommissioned Savannah Project and incorporate improved payabilities for certain contained metals compared to the 2010 Extended Concentrate Sales Agreement. Panoramic believes that the terms of the Agreement are highly competitive in the global market for Savannah’s bulk nickel-copper-cobalt concentrate, based on the bids for the concentrate received from a number of parties and the knowledge that the market for nickel concentrates has tightened significantly in the past 12 months. The general terms and conditions of the new Agreement are as follows: • Product – sulphide concentrate with a typical specification of 8% Ni, 4.5% Cu, 0.6% Co, 46% Fe, <1.0% MgO; • Quantity (in-bulk) – 100% of production from the Savannah Project; • Load Port – Wyndham, Western Australia; • Payable metals – Ni, Cu and Co; • Price basis – agreed % of LME cash price for Ni and Cu and agreed % of Metal Bulletin Co price; and • Life of new contract - 4 years commencing from the date of the first shipment or 31 March 2019, whichever occurs first.