Children's Suffrage: Giving 16 Year Olds the Right to Vote

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Legal Protection of Youth Suffrage

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 349 6th International Conference on Community Development (ICCD 2019) Legal Protection of Youth Suffrage Imam Ropii Hb. Sujiantoro University of Wisnuwardhana Malang University of Wisnuwardhana Malang [email protected] Abstract. As a large number of young voters still have The implementation of an accountable and responsive no identity card (Indonesian: Kartu Tanda democratic system of government embodied in each state Penduduk/KTP), the legal protection of youth policy formation always cooperates or involves people's suffrage is becoming a discourse by the General representation that has been elected and determined Election on 17 April 2019. Distribution of eligible through general elections [1]. citizens’ suffrage must be prevented from any According to Mahfud MD, the substance of the obstacles, mainly administrative issue. To the young democratic system places the people as the main subject voters, as the age when registering for the vote are not in every state policymaking through its representatives in old enough according to the law, the population the people's representative institutions [2]. administration office is unable to provide electronic The guarantee of the legal protection of citizens' identity cards (KTPE), resulting in them not being suffrage in general elections as regulated by the electoral registered as voters. The lack of electoral literacy and legal framework must be interpreted as an obligation to the constraints of administrative requirements make the government and elections organizers as well as the young voters vulnerable to losing their voting citizens to be realized. Likewise, the mass media plays a rights. A National Identification Number role as a controller and voicer if the implementation of (Indonesian: Nomor Induk Kependudukan, NIK) as the citizens' suffrage protection is hampered or cannot be the single identity number of each resident is listed on implemented due to the electoral law, population the family card (Indonesian: Kartu Keluarga, KK). -

Homeschooling and the Question of Socialization Revisited

Homeschooling and the Question of Socialization Revisited Richard G. Medlin Stetson University This article reviews recent research on homeschooled children’s socialization. The research indicates that homeschooling parents expect their children to respect and get along with people of diverse backgrounds, provide their children with a variety of social opportunities outside the family, and believe their children’s social skills are at least as good as those of other children. What homeschooled children think about their own social skills is less clear. Compared to children attending conventional schools, however, research suggest that they have higher quality friendships and better relationships with their parents and other adults. They are happy, optimistic, and satisfied with their lives. Their moral reasoning is at least as advanced as that of other children, and they may be more likely to act unselfishly. As adolescents, they have a strong sense of social responsibility and exhibit less emotional turmoil and problem behaviors than their peers. Those who go on to college are socially involved and open to new experiences. Adults who were homeschooled as children are civically engaged and functioning competently in every way measured so far. An alarmist view of homeschooling, therefore, is not supported by empirical research. It is suggested that future studies focus not on outcomes of socialization but on the process itself. Homeschooling, once considered a fringe movement, is now widely seen as “an acceptable alternative to conventional schooling” (Stevens, 2003, p. 90). This “normalization of homeschooling” (Stevens, 2003, p. 90) has prompted scholars to announce: “Homeschooling goes mainstream” (Gaither, 2009, p. 11) and “Homeschooling comes of age” (Lines, 2000, p. -

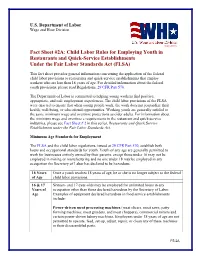

Child Labor Rules for Employing Youth in Restaurants and Quick-Service Establishments Under the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA)

U.S. Department of Labor Wage and Hour Division (July 2010) Fact Sheet #2A: Child Labor Rules for Employing Youth in Restaurants and Quick-Service Establishments Under the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) This fact sheet provides general information concerning the application of the federal child labor provisions to restaurants and quick-service establishments that employ workers who are less than 18 years of age. For detailed information about the federal youth provisions, please read Regulations, 29 CFR Part 570. The Department of Labor is committed to helping young workers find positive, appropriate, and safe employment experiences. The child labor provisions of the FLSA were enacted to ensure that when young people work, the work does not jeopardize their health, well-being, or educational opportunities. Working youth are generally entitled to the same minimum wage and overtime protections as older adults. For information about the minimum wage and overtime e requirements in the restaurant and quick-service industries, please see Fact Sheet # 2 in this series, Restaurants and Quick Service Establishment under the Fair Labor Standards Act. Minimum Age Standards for Employment The FLSA and the child labor regulations, issued at 29 CFR Part 570, establish both hours and occupational standards for youth. Youth of any age are generally permitted to work for businesses entirely owned by their parents, except those under 16 may not be employed in mining or manufacturing and no one under 18 may be employed in any occupation the Secretary of Labor has declared to be hazardous. 18 Years Once a youth reaches 18 years of age, he or she is no longer subject to the federal of Age child labor provisions. -

Youth Declaration of Rights Vermont Youth Have the Right To

YOUTH DECLARATION OF RIGHTS VERMONT YOUTH HAVE THE RIGHT TO: EDUCATION MENTAL HEALTH Access free classes on Basic Life Skills (signing a lease, Have access to affordable mental health care budgeting, taxes, resumes, etc.) A personal break to handle their mental situation Equal opportunities and experiences in arts education Choose their own identity, whether that be sexual before, during, and after school orientation, religious identification, and/or gender A post-secondary education no matter their financial identification situation Have people in society who support their mental well-being A student-directed, safe space for afterschool support and community engagement free of charge NATURAL ENVIRONMENT Time outdoors during the school (or work) day A healthy environment that provides the basic necessities to all life Know about the environment, and what is being done to it EQUALITY & JUSTICE Have a say about what happens to the environment Explore their identities in a safe environment Safe recreation in the outdoors and in their communities Education on gun safety and to live in a gun-aware PHYSICAL HEALTH community that is educated and aware of proper gun usage Hygienic products, clothing, and utilities suitable for all Have their voices heard in legal decisions that affect climates and environments everyone Have access to outdoor recreational and natural spaces Be protected in all of their life circumstances, be able to (e.g., parks, fields, courts, lakes, pitches, trails, paths, etc.) have their own privacy in their environments, -

19Th Amendment Conference | CLE Materials

The 19th Amendment at 100: From the Vote to Gender Equality Center for Constitutional Law at The University of Akron School of Law Friday, Sept. 20, 2019 CONTINUING EDUCATION MATERIALS More information about the Center for Con Law at Akron available on the Center website, https://www.uakron.edu/law/ccl/ and on Twitter @conlawcenter 001 Table of Contents Page Conference Program Schedule 3 Awakening and Advocacy for Women’s Suffrage Tracy Thomas, More Than the Vote: The 19th Amendment as Proxy for Gender Equality 5 Richard H. Chused, The Temperance Movement’s Impact on Adoption of Women’s Suffrage 28 Nicole B. Godfrey, Suffragist Prisoners and the Importance of Protecting Prisoner Protests 53 Amending the Constitution Ann D. Gordon, Many Pathways to Suffrage, Other Than the 19th Amendment 74 Paula A. Monopoli, The Legal and Constitutional Development of the Nineteenth Amendment in the Decade Following Ratification 87 Keynote: Ellen Carol DuBois, The Afterstory of the Nineteth Amendment, Outline 96 Extensions and Applications of the Nineteenth Amendment Cornelia Weiss The 19th Amendment and the U.S. “Women’s Emancipation” Policy in Post-World War II Occupied Japan: Going Beyond Suffrage 97 Constitutional Meaning of the Nineteenth Amendment Jill Elaine Hasday, Fights for Rights: How Forgetting and Denying Women’s Struggles for Equality Perpetuates Inequality 131 Michael Gentithes, Felony Disenfranchisement & the Nineteenth Amendment 196 Mae C. Quinn, Caridad Dominguez, Chelsea Omega, Abrafi Osei-Kofi & Carlye Owens, Youth Suffrage in the United States: Modern Movement Intersections, Connections, and the Constitution 205 002 THE CENTER FOR CONSTITUTIONAL LAW AT AKRON th The 19 Amendment at 100: From the Vote to Gender Equality Friday, September 20, 2019 (8am to 5pm) The University of Akron School of Law (Brennan Courtroom 180) The focus of the 2019 conference is the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment. -

Lawmakers Are Mulling Multiple Bills That Would Let Cities and Towns Allow

for purchasing tobacco products. Lyons added that lowering the voting age would be detrimental to “all the great work that has been achieved,” on age-related issues. “On the one hand, they don’t trust people under 21 to buy tobacco products, but, on the other, they want to give much younger people the right to vote,” Tuerck said. “We have to wonder where this thinking comes from.” People also have to be 21 to buy alcohol and marijuana in Massachusetts. The age limit for the juvenile justice system was raised from 17 to 18 in 2013, and lawmakers have looked at raising it to 21. While in high school, Vargas was involved in a five- year campaign with UTEC, the state have asked to be given formerly known as United Teen Lawmakers are mulling Equality Center, advocating multiple bills that would let cities the authority to lower the voting age for municipal elections. alongside other young adults in and towns allow teens as young Lowell to lower the voting age to as 16 to vote in local elections, “It is time to give municipalities the option to empower their own 17. The city passed a home rule a move critics are calling petition in 2015, but it ultimately “frivolous” and “absurd.” young people,” Chandler said. “Cities and towns stalled in the Legislature. Two bills that would “This is about local allow “every citizen 16 or 17 have asked for this option for years, and I believe that control,” Vargas said. “You years of age, who is a resident don’t have to agree with in the city or town where he or young people deserve a voice in their local -

National Youth Rights Association Jason Kende

Board of Directors PO Box 5882 Christopher Coes -- Washington DC 20016 Scott Davidson http://www.youthrights.org [email protected] Laura Finstad Rich Jahn National Youth Rights Association Jason Kende Alex Koroknay-Palicz Johnathan McClure To: Federal Elections Commission Re: Rules regarding political contributions by minors Kathleen Miller Brad White In light of the December 10 Supreme Court's use of no uncertain terms in to strike down the Bi-Partisan Campaign Reform Act's provision that Board of Advisors individuals 17 and under were banned from political giving, the National Youth Rights Association urges a liberal interpretation of the rules Adam Fletcher when implementing the Court's ruling. To accommodate the decision Founder, Freechild.org in McConnell vs. FEC we believe the greatest deference must be paid David Hanson, Ph. D. to youth wanting to donate money to political campaigns and parties. Professor. State University ofNew York at Potsdam Specifically we recommend the following: 1. Minors 14-17 should be treated no differently from adults in the Bennett Haselton area of political donations. President. Peacefire 2. Minors between 7 and 14 should have an initial presumption of Grace Llewellyn capacity that is rebuttable. Author. "Teenage Liberation Handbook" 3. Minors 7 and under should have a rebuttable presumption of incapacity. Mike Males, Ph.D. 4. Minors should be able to donate from bank accounts where they Author. "Framing Youth" have full access to the funds, even if parents or guardians must Roderic Park, Ph. D. co-sign to open the account. Former chancellor. University ofColorado - If a hearing is scheduled, NYRA is interested in testifying. -

Leveraging Youth Advocacy May 5, 2021

School Mental Health Virtual Learning Series January 2021-August 2021 Youth MOVE National: Leveraging Youth Advocacy May 5, 2021 Technology Support • Slides will be posted on the NCSMH website (www.schoolmentalhealth.org) and emailed after the presentation to all registrants • Please type questions for the panelists into the Q&A box. • Use chat box for sharing resources, comments, and responding to speaker Web Mobile App Tiffany Beason Larraine Bernstein Taneisha Carter Elizabeth Connors NCSMH Faculty Coordinator Senior RA NCSMH Faculty Dana Cunningham Sharon Hoover Nancy Lever Jill PGSMHI Director NCSMH Co-Director NCSMH Co-Director Bohnenkamp NCSMH Faculty Oscar Morgan Michael Thompson Dave Brown MHTTC Project Director MHTTC Sr. TA Specialist Senior Associate School-based Training Behavioral Health Equities Perrin Robinson Britt Patterson Kris Scardamalia Communications Director NCSMH Faculty NCSMH Faculty Central East Geographical Area of Focus HHS REGION 3 Delaware District of Columbia Maryland Pennsylvania Virginia West Virginia What Does Central East MHTTC Do? Actions • Accelerate the adoption and implementation of evidence‐based and promising treatment and recovery-oriented practices and services • Strengthen the awareness, knowledge, and skills of the behavioral and mental health and prevention workforce, and other stakeholders, that address the needs of people with behavioral health disorders • Foster regional and national alliances among culturally diverse practitioners, researchers, policy makers, funders, and the recovery community • Ensure the availability and delivery of publicly available, free of charge, training and technical assistance to the behavioral and mental health field National Center for School Mental Health MISSION: Strengthen policies and programs in school mental health to improve learning and promote success for America's youth • Focus on advancing school mental health policy, research, practice, and training • Shared family-schools-community mental health agenda Directors: Drs. -

Why We Should Raise the Marriage Age Vivian E

College of William & Mary Law School William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository Popular Media Faculty and Deans 2013 Why We Should Raise the Marriage Age Vivian E. Hamilton William & Mary Law School, [email protected] Repository Citation Hamilton, Vivian E., "Why We Should Raise the Marriage Age" (2013). Popular Media. 123. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/popular_media/123 Copyright c 2013 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/popular_media 5/14/13 Concurring Opinions » Why We Should Raise the Marriage Age » Print - Concurring Opinions - http://www.concurringopinions.com - Why We Should Raise the Marriage Age Posted By Vivian Hamilton On January 30, 2013 @ 6:31 pm In Family Law,Uncategorized | 6 Comments [1]My last series of posts [2] argued that states should lower the voting age, since by mid-adolescence, teens have the cognitive-processing and reasoning capacities required for voting competence. But that is not to say that teens have attained adult-like capacities across all domains. To the contrary, context matters. And one context in which teens lack competence is marriage. Through a single statutory adjustment — raising to 21 the age at which individuals may marry — legislators could reduce the percentage of marriages ending in divorce, improve women’s mental and physical health, and elevate women’s and children’s socioeconomic status. More than 1 in 10 U.S. women surveyed between 2001 and 2002 had married before age 18, with 9.4 million having married at age 16 or younger. In 2010, some 520,000 U.S. -

Download Issue

YOUTH &POLICY No. 116 MAY 2017 Youth & Policy: The final issue? Towards a new format Editorial Group Paula Connaughton, Ruth Gilchrist, Tracey Hodgson, Tony Jeffs, Mark Smith, Jean Spence, Naomi Thompson, Tania de St Croix, Aniela Wenham, Tom Wylie. Associate Editors Priscilla Alderson, Institute of Education, London Sally Baker, The Open University Simon Bradford, Brunel University Judith Bessant, RMIT University, Australia Lesley Buckland, YMCA George Williams College Bob Coles, University of York John Holmes, Newman College, Birmingham Sue Mansfield, University of Dundee Gill Millar, South West Regional Youth Work Adviser Susan Morgan, University of Ulster Jon Ord, University College of St Mark and St John Jenny Pearce, University of Bedfordshire John Pitts, University of Bedfordshire Keith Popple, London South Bank University John Rose, Consultant Kalbir Shukra, Goldsmiths University Tony Taylor, IDYW Joyce Walker, University of Minnesota, USA Anna Whalen, Freelance Consultant Published by Youth & Policy, ‘Burnbrae’, Black Lane, Blaydon Burn, Blaydon on Tyne NE21 6DX. www.youthandpolicy.org Copyright: Youth & Policy The views expressed in the journal remain those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Editorial Group. Whilst every effort is made to check factual information, the Editorial Group is not responsible for errors in the material published in the journal. ii Youth & Policy No. 116 May 2017 About Youth & Policy Youth & Policy Journal was founded in 1982 to offer a critical space for the discussion of youth policy and youth work theory and practice. The editorial group have subsequently expanded activities to include the organisation of related conferences, research and book publication. Regular activities include the bi- annual ‘History of Community and Youth Work’ and the ‘Thinking Seriously’ conferences. -

Making Exceptions to Universal Suffrage: Disability and the Right to Vote

Making Exceptions to Universal Suffrage: Disability and the Right to Vote Kay Schriner, University of Arkansas Lisa Ochs, Arkansas State University In C.E. Faupel & P.M. Roman (Eds.), Encyclopedia of criminology and deviant behavior 179-183. London: Taylore & Francis. 2000. The history of Western representative democracies is marked by disputes over who constitutes the electorate. In the U.S., where states have the prerogative of establishing voter qualifications, categories such as race and gender have been used during various periods to disqualify millions of individuals from participating in elections. These restrictions have long been considered an infamous example of the failings of democratic theorists and practitioners to overcome the prejudices of their time. Less well-known is the common practice of disenfranchising other large numbers of adults. Indeed, very few American citizens are aware that there are still two groups who are routinely targeted for disenfranchisement - criminals and individuals with disabilities. These laws, which arguably perpetuate racial and disability discrimination, are vestiges of earlier attempts to cordon off from democracy those who were believed to be morally and intellectually inferior. This entry describes these disability-based disenfranchisements, and briefly discusses the political, economic, and social factors associated with their adoption. Disenfranchising People with Cognitive and Emotional Impairments Today, forty-four states disenfranchise some individuals with cognitive and emotional impairments. States use a variety of categories to identify such individuals, including idiot, insane, lunatic, mental incompetent, mental incapacitated, being of unsound mind, not quiet and peaceable, and under guardianship and/or conservatorship. Fifteen states disenfranchise individuals who are idiots, insane, and/or lunatics. -

The Drinking Age

Vermont Legislative Research Shop Lowering the Drinking Age The minimum legal drinking age fluctuated throughout the second half of the 20th century, yielding mixed results. After prohibition was repealed in 1933, almost every state set the minimum legal drinking age (MLDA) at 21 years.1 In 1970 Congress lowered the voting age to 18, which began a movement to lower the drinking age, as well. During the Vietnam era, many people were outraged that 18 year‐olds were fighting overseas yet could not have a drink. In the period between 1970 and 1975, 29 states lowered their MLDA to 18, 19 or 20. A study by Alexander Wagenaar revealed that in states that had lowered their minimum age there was a 15 to 20% increase in teen automobile accidents.2 This information influenced 16 states to raise their MLDA to 21 between 1976 and 1983. Pressure from groups such as Mothers Against Drunk Driving (MADD) led to the signing of the Uniform Drinking Age Act by President Ronald Reagan on July 17, 1984.3 This act mandated a significant decrease in federal transportation funding for states that did not raise their MLDA to 21. Worldwide, the United States has the highest MLDA, with others ranging from birth to age 20.4 The majority of countries have a MLDA of 18. In most of these countries, however, the family teaches responsible drinking from a very young age. Since 1960, over one hundred studies have been conducted to analyze the effects of raising the MLDA. This research was examined by Alexander Wagenaar to determine the trends that appeared in the conclusions.5 Some of these studies provided evidence supporting a MLDA of 21, while most others found no conclusive results.