Final Report of the Inuit Bowhead Knowledge Study March 2000

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Of the Inuit Bowhead Knowledge Study Nunavut, Canada

english cover 11/14/01 1:13 PM Page 1 FINAL REPORT OF THE INUIT BOWHEAD KNOWLEDGE STUDY NUNAVUT, CANADA By Inuit Study Participants from: Arctic Bay, Arviat, Cape Dorset, Chesterfield Inlet, Clyde River, Coral Harbour, Grise Fiord, Hall Beach, Igloolik, Iqaluit, Kimmirut, Kugaaruk, Pangnirtung, Pond Inlet, Qikiqtarjuaq, Rankin Inlet, Repulse Bay, and Whale Cove Principal Researchers: Keith Hay (Study Coordinator) and Members of the Inuit Bowhead Knowledge Study Committee: David Aglukark (Chairperson), David Igutsaq, MARCH, 2000 Joannie Ikkidluak, Meeka Mike FINAL REPORT OF THE INUIT BOWHEAD KNOWLEDGE STUDY NUNAVUT, CANADA By Inuit Study Participants from: Arctic Bay, Arviat, Cape Dorset, Chesterfield Inlet, Clyde River, Coral Harbour, Grise Fiord, Hall Beach, Igloolik, Iqaluit, Kimmirut, Kugaaruk, Pangnirtung, Pond Inlet, Qikiqtarjuaq, Rankin Inlet, Nunavut Wildlife Management Board Repulse Bay, and Whale Cove PO Box 1379 Principal Researchers: Iqaluit, Nunavut Keith Hay (Study Coordinator) and X0A 0H0 Members of the Inuit Bowhead Knowledge Study Committee: David Aglukark (Chairperson), David Igutsaq, MARCH, 2000 Joannie Ikkidluak, Meeka Mike Cover photo: Glenn Williams/Ursus Illustration on cover, inside of cover, title page, dedication page, and used as a report motif: “Arvanniaqtut (Whale Hunters)”, sc 1986, Simeonie Kopapik, Cape Dorset Print Collection. ©Nunavut Wildlife Management Board March, 2000 Table of Contents I LIST OF TABLES AND FIGURES . .i II DEDICATION . .ii III ABSTRACT . .iii 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 RATIONALE AND BACKGROUND FOR THE STUDY . .1 1.2 TRADITIONAL ECOLOGICAL KNOWLEDGE AND SCIENCE . .1 2 METHODOLOGY 3 2.1 PLANNING AND DESIGN . .3 2.2 THE STUDY AREA . .4 2.3 INTERVIEW TECHNIQUES AND THE QUESTIONNAIRE . .4 2.4 METHODS OF DATA ANALYSIS . -

Procurement Activity Report 2016-2017

GOVERNMENT OF NUNAVUT Procurement Activity Repor t kNo1i Z?m4fiP9lre pWap5ryeCd6 t b4fy 5 Nunalingni Kavamatkunnilu Pivikhaqautikkut Department of Community and Government Services Ministère des Services communautaires et gouvernementaux Fiscal Year 2016/17 GOVERNMENT OF NUNAVUT Procurement Activity Report Table of Contents Purpose . 3 Objective . 3 Introduction . 3 Report Overview . 4 Sole Source Contract Observations . 5 General Observations . 9 Summary . 11 1. All Contracts (> $5,000) . 11 2. Contracting Types . 15 3. Contracting Methods . 18 4. Sole Source Contract Distribution . 22 Appendices Appendix A: Glossary and Definition of Terms . 27 Appendix B: Sole Source (> $5,000) . 29 Appendix C: Contract Detailed Listing (> $5,000) . 31 1 GOVERNMENT OF NUNAVUT Procurement Activity Report Purpose The Department of Community and Government Services (CGS) is pleased to present this report on the Government of Nunavut (GN's) procurement and contracting activities for the 2016/17 fiscal year. Objective CGS is committed to ensuring fair value and ethical practices in meeting its responsibilities. This is accomplished through effective policies and procedures aimed at: • Obtaining the best value for Nunavummiut overall; • Creating a fair and open environment for vendors; • Maintaining current and accurate information; and • Ensuring effective approaches to meet the GN's requirements. Introduction The Procurement Activity Report presents statistical information and contract detail about GN contracts as reported by GN departments to CGS's Procurement, Logistics and Contract Support section. Contracts entered into by the GN Crown agencies and the Legislative Assembly are not reported to CGS and are not included in this report. Contract information provided in this report reflects contracts awarded and reported during the 2016/2017 fiscal year. -

Bathurst Fact Sheet

Qausuittuq National Park Update on the national park proposal on Bathurst Island November 2012 Parks Canada, the Qikiqtani Inuit Association (QIA) and the community of Resolute Bay are working together to create a new national park on Bathurst Island, Nunavut. The purpose of the park is to protect an area within the The park will be managed in co-operation with Inuit for Western High Arctic natural region of the national park the benefit, education and enjoyment of all Canadians. system, to conserve wildlife and habitat, especially areas It is expected that the park’s establishment will enhance important to Peary caribou, and enable visitors to learn and support local employment and business as well as about the area and its importance to Inuit. help strengthen the local and regional economies. Qausuittuq National Park and neighbouring Polar Bear Within the park, Inuit will continue to exercise their Pass National Wildlife Area will together ensure protec - right to subsistence harvesting. tion of most of the northern half of Bathurst Island as well as protection of a number of smaller nearby islands. Bringing you Canada’s natural and historic treasures Did you know? After a local contest, the name of the proposed national park was selected as Qausuittuq National Park. Qausuittuq means “place where the sun does - n't rise” in Inuktitut, in reference to the fact that the sun stays below the horizon for several months in the winter at this latitude. What’s happening? Parks Canada and Qikiqtani Inuit Association (QIA) are working towards completion and rati - fication of an Inuit Impact and Benefit Agree - ment (IIBA). -

Imaging Laurentide Ice Sheet Drainage Into the Deep Sea: Impact on Sediments and Bottom Water

Imaging Laurentide Ice Sheet Drainage into the Deep Sea: Impact on Sediments and Bottom Water Reinhard Hesse*, Ingo Klaucke, Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec H3A 2A7, Canada William B. F. Ryan, Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory of Columbia University, Palisades, NY 10964-8000 Margo B. Edwards, Hawaii Institute of Geophysics and Planetology, University of Hawaii, Honolulu, HI 96822 David J. W. Piper, Geological Survey of Canada—Atlantic, Bedford Institute of Oceanography, Dartmouth, Nova Scotia B2Y 4A2, Canada NAMOC Study Group† ABSTRACT the western Atlantic, some 5000 to 6000 State-of-the-art sidescan-sonar imagery provides a bird’s-eye view of the giant km from their source. submarine drainage system of the Northwest Atlantic Mid-Ocean Channel Drainage of the ice sheet involved (NAMOC) in the Labrador Sea and reveals the far-reaching effects of drainage of the repeated collapse of the ice dome over Pleistocene Laurentide Ice Sheet into the deep sea. Two large-scale depositional Hudson Bay, releasing vast numbers of ice- systems resulting from this drainage, one mud dominated and the other sand bergs from the Hudson Strait ice stream in dominated, are juxtaposed. The mud-dominated system is associated with the short time spans. The repeat interval was meandering NAMOC, whereas the sand-dominated one forms a giant submarine on the order of 104 yr. These dramatic ice- braid plain, which onlaps the eastern NAMOC levee. This dichotomy is the result of rafting events, named Heinrich events grain-size separation on an enormous scale, induced by ice-margin sifting off the (Broecker et al., 1992), occurred through- Hudson Strait outlet. -

A Historical and Legal Study of Sovereignty in the Canadian North : Terrestrial Sovereignty, 1870–1939

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository University of Calgary Press University of Calgary Press Open Access Books 2014 A historical and legal study of sovereignty in the Canadian north : terrestrial sovereignty, 1870–1939 Smith, Gordon W. University of Calgary Press "A historical and legal study of sovereignty in the Canadian north : terrestrial sovereignty, 1870–1939", Gordon W. Smith; edited by P. Whitney Lackenbauer. University of Calgary Press, Calgary, Alberta, 2014 http://hdl.handle.net/1880/50251 book http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives 4.0 International Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca A HISTORICAL AND LEGAL STUDY OF SOVEREIGNTY IN THE CANADIAN NORTH: TERRESTRIAL SOVEREIGNTY, 1870–1939 By Gordon W. Smith, Edited by P. Whitney Lackenbauer ISBN 978-1-55238-774-0 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at ucpress@ ucalgary.ca Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specificwork without breaching the artist’s copyright. -

Diapositive 1

CLEANING-UP DEW LINE SITES IN NUNAVUT: THE INUIT PERSPECTIVE AT CAM-F Kailapi Alorut, Jean-Pierre Pelletier and Michel Pouliot CLEANING-UP DEW LINE SITES IN NUNAVUT: The Inuit Perspective at CAM-F (Kinguraq) • Location of Iglulik (Igloolik) • Presentation of Iglulik and Sanirajaq (Hall Beach) • Use of the Kinguraq area • CAM-F Cleanup Project Summary • Mobilization to the Site • On-Site Activities • Project Local Requirements • Regional Pressure • Inuit Content • Local Benefits Site Location and History Iglulik Sanirajak 900 km Yellowknife Iqaluit Kuujjuaq Iglulik (or Igloolik) • Igloolik means "there is an igloo here" • First Settlement: 4,000 years • Roman Catholic Mission and RCMP detachment in the 1930s • Over 1,500 people • Igloolik Isuma Productions Inc. • Artcirq Sanirajak (or Hall Beach)« • Sanirajak, means "one that is along the coast" • Created with the DEW Line Radar System • Hall Beach is NWS site • Population is approximately 600 people Site Location and History • CAM-F is one of the 13 DEW Line Radar Stations located within the Qikiqtaaluk Region of Nunavut • One of the 4 landlocked Stations (FOX-3, FOX-B and CAM- D are the other three) Location of Kingurak (Sarcpa Lake) Iglulik 100 km Sanirajak 85 km Kingurak Use of the Kingurak Area CAM-F Cleanup: Before and After Pictures: UMA/AECOM CLEANING-UP DEW LINE SITES IN NUNAVUT: The Inuit Perspective at CAM-F (Kinguraq) Mobilization: Sealift and CAT-Train Route 55 km 40 km 30 km Total CAT-Train Distance: Hall Beach – CAM-F: 125 km The Construction Camp Debris Collection Barrel -

EXPERIENCES 2021 Table of Contents

NUNAVUT EXPERIENCES 2021 Table of Contents Arts & Culture Alianait Arts Festival Qaggiavuut! Toonik Tyme Festival Uasau Soap Nunavut Development Corporation Nunatta Sunakkutaangit Museum Malikkaat Carvings Nunavut Aqsarniit Hotel And Conference Centre Adventure Arctic Bay Adventures Adventure Canada Arctic Kingdom Bathurst Inlet Lodge Black Feather Eagle-Eye Tours The Great Canadian Travel Group Igloo Tourism & Outfitting Hakongak Outfitting Inukpak Outfitting North Winds Expeditions Parks Canada Arctic Wilderness Guiding and Outfitting Tikippugut Kool Runnings Quark Expeditions Nunavut Brewing Company Kivalliq Wildlife Adventures Inc. Illu B&B Eyos Expeditions Baffin Safari About Nunavut Airlines Canadian North Calm Air Travel Agents Far Horizons Anderson Vacations Top of the World Travel p uit O erat In ed Iᓇᓄᕗᑦ *denotes an n u q u ju Inuit operated nn tau ut Aula company About Nunavut Nunavut “Our Land” 2021 marks the 22nd anniversary of Nunavut becoming Canada’s newest territory. The word “Nunavut” means “Our Land” in Inuktut, the language of the Inuit, who represent 85 per cent of Nunavut’s resident’s. The creation of Nunavut as Canada’s third territory had its origins in a desire by Inuit got more say in their future. The first formal presentation of the idea – The Nunavut Proposal – was made to Ottawa in 1976. More than two decades later, in February 1999, Nunavut’s first 19 Members of the Legislative Assembly (MLAs) were elected to a five year term. Shortly after, those MLAs chose one of their own, lawyer Paul Okalik, to be the first Premier. The resulting government is a public one; all may vote - Inuit and non-Inuit, but the outcomes reflect Inuit values. -

20110110 CMO Maps

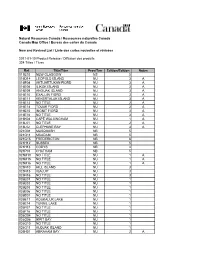

Natural Resources Canada / Ressources naturelles Canada Canada Map Office / Bureau des cartes du Canada New and Revised List / Liste des cartes nouvelles et révisées 2011-01-10 Product Release / Diffusion des produits 324 Titles / Titres Ref. Title/Titre Prov/Terr Edition/Édition Notes 011E10 NEW GLASGOW NS 5 016D14 LEOPOLD ISLAND NU 3 A 016E04 AKTIJARTUKAN FIORD NU 3 A 016E06 ILIKOK ISLAND NU 3 A 016E09 ANGIJAK ISLAND NU 3 A 016E10 EXALUIN FIORD NU 3 A 016E11 KEKERTALUK ISLAND NU 3 A 016E13 NO TITLE NU 2 A 016E14 TOUAK FIORD NU 2 A 016E15 INGNIT FIORD NU 3 A 016E16 NO TITLE NU 3 A 016K04 CAPE WALSINGHAM NU 1 A 016L01 NO TITLE NU 2 A 016L02 CLEPHANE BAY NU 3 A 021G01 MUSQUASH NB 5 021G11 MCADAM NB 5 021G15 FREDERICTON NB 6 021H12 SUSSEX NB 5 021H13 CODYS NB 4 021P03 CHATHAM NB 5 025M10 NO TITLE NU 1 A 025M15 NO TITLE NU 1 A 025M16 NO TITLE NU 1 A 025N10 HILL ISLAND NU 3 025N15 IQALUIT NU 3 025N16 NO TITLE NU 3 026E01 NO TITLE NU 1 026E02 NO TITLE NU 1 026E03 NO TITLE NU 1 026E06 NO TITLE NU 1 026E07 NO TITLE NU 1 026E11 KOUKALUK LAKE NU 1 026E14 TUNNIL LAKE NU 1 026F07 NO TITLE NU 1 026F16 NO TITLE NU 1 026G04 NO TITLE NU 1 026G06 IKPIT BAY NU 1 026G10 NO TITLE NU 1 026G11 KUDJAK ISLAND NU 1 026H01 ABRAHAM BAY NU 2 A 026H02 QUEENS CAPE NU 2 A 026H06 SHOMEO POINT NU 2 A 026H07 KUMLIEN FIORD NU 2 A 026H08 UJUKTUK FIORD NU 2 A 026H10 NO TITLE NU 2 A 026H11 IQALUJJUAQ FIORD NU 2 A 026H12 KEKERTEN ISLAND NU 2 A 026H13 KEKERTUKDJUAK ISLAND NU 2 A 026H14 NO TITLE NU 2 A 026I03 KINGNAIT HARBOUR NU 2 A 026I04 PANGNIRTUNG NU 2 A 026I05 MOON PEAK -

Summary of the Hudson Bay Marine Ecosystem Overview

i SUMMARY OF THE HUDSON BAY MARINE ECOSYSTEM OVERVIEW by D.B. STEWART and W.L. LOCKHART Arctic Biological Consultants Box 68, St. Norbert P.O. Winnipeg, Manitoba CANADA R3V 1L5 for Canada Department of Fisheries and Oceans Central and Arctic Region, Winnipeg, Manitoba R3T 2N6 Draft March 2004 ii Preface: This report was prepared for Canada Department of Fisheries and Oceans, Central And Arctic Region, Winnipeg. MB. Don Cobb and Steve Newton were the Scientific Authorities. Correct citation: Stewart, D.B., and W.L. Lockhart. 2004. Summary of the Hudson Bay Marine Ecosystem Overview. Prepared by Arctic Biological Consultants, Winnipeg, for Canada Department of Fisheries and Oceans, Winnipeg, MB. Draft vi + 66 p. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION.........................................................................................................................1 2.0 ECOLOGICAL OVERVIEW.........................................................................................................3 2.1 GEOLOGY .....................................................................................................................4 2.2 CLIMATE........................................................................................................................6 2.3 OCEANOGRAPHY .........................................................................................................8 2.4 PLANTS .......................................................................................................................13 2.5 INVERTEBRATES AND UROCHORDATES.................................................................14 -

Community Wellness Plan Arviat

Community Wellness Plan Arviat Prepared by: Arviat Community Wellness Working Group as Part of the Nunavut Community Wellness Project. Arviat Community Wellness Plan The Nunavut Community Wellness Project was a tripartite project led by Nunavut Tunngavik Inc. in partnership with Government of Nunavut, Department of Health and Social Services and Health Canada. Photographic images on cover, inside front cover, table of contents, headers and on pages 2, 11 and 12 taken by Kukik Tagalik. July, 2011 table of contents PAGE 2 1. Introduction 2 2. Community Wellness Working Group 3 2.1 Purpose of Working Group 3 2.2 Objectives of the Nunavut Community Wellness Working Groups 3 2.3 Description of the Group 4 3. Community Overview 4 4. Creating Awareness in the Community 4 4.1 Description of Community-Based Awareness Activities 5 5. What are the Resources in Our Community 5 5.1 Community Map and Description (From Assets Exercise) 5 5.2 Community Assets and Description (From Asset Exercise) 7 6. Issues Identification 7 6.1 Process for Identifying Issues 7 6.2 What are the Issues 7 7. Community Vision for Wellness 7 7.1 Process for Identifying Vision 7 7.2 Community Goals (Prioritized) 8 8. Community Plan 8 8.1 Connecting Assets to Wellness Vision (from Assets Exercise) 10 8.2 Steps to Reach Goals and Objectives 12 9. Conclusions 12 9.1 Establish a Community Wellness Working Group 12 9.2 The Hiring of the Pilot Coordinator 12 9.3 Development of a Community Wellness Planning Process 13 9.4 Presentation of Recommendations to the Hamlet Council 13 9.5 Ongoing Communication and Work 13 10. -

Who Discovered the Northwest Passage? Janice Cavell1

ARCTIC VOL. 71, NO.3 (SEPTEMBER 2018) P.292 – 308 https://doi.org/10.14430/arctic4733 Who Discovered the Northwest Passage? Janice Cavell1 (Received 31 January 2018; accepted in revised form 1 May 2018) ABSTRACT. In 1855 a parliamentary committee concluded that Robert McClure deserved to be rewarded as the discoverer of a Northwest Passage. Since then, various writers have put forward rival claims on behalf of Sir John Franklin, John Rae, and Roald Amundsen. This article examines the process of 19th-century European exploration in the Arctic Archipelago, the definition of discovering a passage that prevailed at the time, and the arguments for and against the various contenders. It concludes that while no one explorer was “the” discoverer, McClure’s achievement deserves reconsideration. Key words: Northwest Passage; John Franklin; Robert McClure; John Rae; Roald Amundsen RÉSUMÉ. En 1855, un comité parlementaire a conclu que Robert McClure méritait de recevoir le titre de découvreur d’un passage du Nord-Ouest. Depuis lors, diverses personnes ont avancé des prétentions rivales à l’endroit de Sir John Franklin, de John Rae et de Roald Amundsen. Cet article se penche sur l’exploration européenne de l’archipel Arctique au XIXe siècle, sur la définition de la découverte d’un passage en vigueur à l’époque, de même que sur les arguments pour et contre les divers prétendants au titre. Nous concluons en affirmant que même si aucun des explorateurs n’a été « le » découvreur, les réalisations de Robert McClure méritent d’être considérées de nouveau. Mots clés : passage du Nord-Ouest; John Franklin; Robert McClure; John Rae; Roald Amundsen Traduit pour la revue Arctic par Nicole Giguère. -

Canadian Arctic Tide Measurement Techniques and Results

International Hydrographie Review, Monaco, LXIII (2), July 1986 CANADIAN ARCTIC TIDE MEASUREMENT TECHNIQUES AND RESULTS by B.J. TAIT, S.T. GRANT, D. St.-JACQUES and F. STEPHENSON (*) ABSTRACT About 10 years ago the Canadian Hydrographic Service recognized the need for a planned approach to completing tide and current surveys of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago in order to meet the requirements of marine shipping and construction industries as well as the needs of environmental studies related to resource development. Therefore, a program of tidal surveys was begun which has resulted in a data base of tidal records covering most of the Archipelago. In this paper the problems faced by tidal surveyors and others working in the harsh Arctic environment are described and the variety of equipment and techniques developed for short, medium and long-term deployments are reported. The tidal characteris tics throughout the Archipelago, determined primarily from these surveys, are briefly summarized. It was also recognized that there would be a need for real time tidal data by engineers, surveyors and mariners. Since the existing permanent tide gauges in the Arctic do not have this capability, a project was started in the early 1980’s to develop and construct a new permanent gauging system. The first of these gauges was constructed during the summer of 1985 and is described. INTRODUCTION The Canadian Arctic Archipelago shown in Figure 1 is a large group of islands north of the mainland of Canada bounded on the west by the Beaufort Sea, on the north by the Arctic Ocean and on the east by Davis Strait, Baffin Bay and Greenland and split through the middle by Parry Channel which constitutes most of the famous North West Passage.