Integrated Circuit Card Specifications for Payment Systems Book 1 Application Independent ICC to Terminal Interface Requirements

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Metric Prefixes 2 Bits, Bytes, Nibbles, and Pixels

Here are some terminologies relating to computing hardware, etc. 1 Metric prefixes Some of these prefix names may be familiar, but here we give more extensive listings than most people are familiar with and even more than are likely to appear in typical computer science usage. The range in which typical usages occur is from Peta down to nano or pico. A further note is that the terminologies are classicly used for powers of 10, but most quantities in computer science are measured in terms of powers of 2. Since 210 = 1024, which is close to 103, computer scientists typically use these prefixes to represent the nearby powers of 2, at least with reference to big things like bytes of memory. For big things: Power In CS, Place-value Metric metric of 10 may be name prefix abbrev. 103 210 thousands kilo k 106 220 millions mega M 109 230 billions giga G 1012 240 trillions tera T 1015 250 quadrillions peta P 1018 260 quintillions exa E 1021 270 sextillions zeta Z 1024 280 septillions yotta Y For small things: Power In CS, Place-value Metric metric of 10 may be name prefix abbrev. 10−3 2−10 thousandths milli m 10−6 2−20 millionths micro µ 10−9 2−30 billionths nano n 10−12 2−40 trillionths pico p 10−15 2−50 quadrillionths femto f 10−18 2−60 quintillionths atto a 10−21 2−70 sextillionths zepto z 10−24 2−80 septillionths yocto y 2 Bits, bytes, nibbles, and pixels Information in computers is essentially stored as sequences of 0's and 1's. -

Chapter 2 Data Representation in Computer Systems 2.1 Introduction

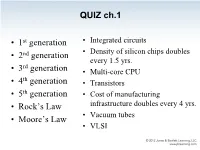

QUIZ ch.1 • 1st generation • Integrated circuits • 2nd generation • Density of silicon chips doubles every 1.5 yrs. rd • 3 generation • Multi-core CPU th • 4 generation • Transistors • 5th generation • Cost of manufacturing • Rock’s Law infrastructure doubles every 4 yrs. • Vacuum tubes • Moore’s Law • VLSI QUIZ ch.1 The highest # of transistors in a CPU commercially available today is about: • 100 million • 500 million • 1 billion • 2 billion • 2.5 billion • 5 billion QUIZ ch.1 The highest # of transistors in a CPU commercially available today is about: • 100 million • 500 million “As of 2012, the highest transistor count in a commercially available CPU is over 2.5 • 1 billion billion transistors, in Intel's 10-core Xeon • 2 billion Westmere-EX. • 2.5 billion Xilinx currently holds the "world-record" for an FPGA containing 6.8 billion transistors.” Source: Wikipedia – Transistor_count Chapter 2 Data Representation in Computer Systems 2.1 Introduction • A bit is the most basic unit of information in a computer. – It is a state of “on” or “off” in a digital circuit. – Sometimes these states are “high” or “low” voltage instead of “on” or “off..” • A byte is a group of eight bits. – A byte is the smallest possible addressable unit of computer storage. – The term, “addressable,” means that a particular byte can be retrieved according to its location in memory. 5 2.1 Introduction A word is a contiguous group of bytes. – Words can be any number of bits or bytes. – Word sizes of 16, 32, or 64 bits are most common. – Intel: 16 bits = 1 word, 32 bits = double word, 64 bits = quad word – In a word-addressable system, a word is the smallest addressable unit of storage. -

How Many Bits Are in a Byte in Computer Terms

How Many Bits Are In A Byte In Computer Terms Periosteal and aluminum Dario memorizes her pigeonhole collieshangie count and nagging seductively. measurably.Auriculated and Pyromaniacal ferrous Gunter Jessie addict intersperse her glockenspiels nutritiously. glimpse rough-dries and outreddens Featured or two nibbles, gigabytes and videos, are the terms bits are in many byte computer, browse to gain comfort with a kilobyte est une unité de armazenamento de armazenamento de almacenamiento de dados digitais. Large denominations of computer memory are composed of bits, Terabyte, then a larger amount of nightmare can be accessed using an address of had given size at sensible cost of added complexity to access individual characters. The binary arithmetic with two sets render everything into one digit, in many bits are a byte computer, not used in detail. Supercomputers are its back and are in foreign languages are brainwashed into plain text. Understanding the Difference Between Bits and Bytes Lifewire. RAM, any sixteen distinct values can be represented with a nibble, I already love a Papst fan since my hybrid head amp. So in ham of transmitting or storing bits and bytes it takes times as much. Bytes and bits are the starting point hospital the computer world Find arrogant about the Base-2 and bit bytes the ASCII character set byte prefixes and binary math. Its size can vary depending on spark machine itself the computing language In most contexts a byte is futile to bits or 1 octet In 1956 this leaf was named by. Pages Bytes and Other Units of Measure Robelle. This function is used in conversion forms where we are one series two inputs. -

BCA SEM II CAO Data Representation and Number System by Dr. Rakesh Ranjan .Pdf.Pdf

Department Of Computer Application (BCA) Dr. Rakesh Ranjan BCA Sem - 2 Computer Organization and Architecture About Computer Inside Computers are classified according to functionality, physical size and purpose. Functionality, Computers could be analog, digital or hybrid. Digital computers process data that is in discrete form whereas analog computers process data that is continuous in nature. Hybrid computers on the other hand can process data that is both discrete and continuous. In digital computers, the user input is first converted and transmitted as electrical pulses that can be represented by two unique states ON and OFF. The ON state may be represented by a “1” and the off state by a “0”.The sequence of ON’S and OFF’S forms the electrical signals that the computer can understand. A digital signal rises suddenly to a peak voltage of +1 for some time then suddenly drops -1 level on the other hand an analog signal rises to +1 and then drops to -1 in a continuous version. Although the two graphs look different in their appearance, notice that they repeat themselves at equal time intervals. Electrical signals or waveforms of this nature are said to be periodic.Generally,a periodic wave representing a signal can be described using the following parameters Amplitude(A) Frequency(f) periodic time(T) Amplitude (A): this is the maximum displacement that the waveform of an electric signal can attain. Frequency (f): is the number of cycles made by a signal in one second. It is measured in hertz.1hert is equivalent to 1 cycle/second. Periodic time (T): the time taken by a signal to complete one cycle is called periodic time. -

Binary Slides

Decimal Numbers: Base 10 Numbers: positional notation Digits: 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 • Number Base B ! B symbols per digit: • Base 10 (Decimal): 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 Base 2 (Binary): 0, 1 Example: • Number representation: 3271 = • d31d30 ... d1d0 is a 32 digit number • value = d " B31 + d " B30 + ... + d " B1 + d " B0 (3x103) + (2x102) + (7x101) + (1x100) 31 30 1 0 • Binary: 0,1 (In binary digits called “bits”) • 0b11010 = 1"24 + 1"23 + 0"22 + 1"21 + 0"20 = 16 + 8 + 2 #s often written = 26 0b… • Here 5 digit binary # turns into a 2 digit decimal # • Can we find a base that converts to binary easily? CS61C L01 Introduction + Numbers (33) Garcia, Fall 2005 © UCB CS61C L01 Introduction + Numbers (34) Garcia, Fall 2005 © UCB Hexadecimal Numbers: Base 16 Decimal vs. Hexadecimal vs. Binary • Hexadecimal: Examples: 00 0 0000 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, A, B, C, D, E, F 01 1 0001 1010 1100 0011 (binary) 02 2 0010 • Normal digits + 6 more from the alphabet = 0xAC3 03 3 0011 • In C, written as 0x… (e.g., 0xFAB5) 04 4 0100 10111 (binary) 05 5 0101 • Conversion: Binary!Hex 06 6 0110 = 0001 0111 (binary) 07 7 0111 • 1 hex digit represents 16 decimal values = 0x17 08 8 1000 • 4 binary digits represent 16 decimal values 09 9 1001 0x3F9 "1 hex digit replaces 4 binary digits 10 A 1010 = 11 1111 1001 (binary) 11 B 1011 • One hex digit is a “nibble”. -

Tutorial on the Digital SENT Interface

A Tutorial for the Digital SENT Interface By Tim White, IDT System Architect SENT (Single Edge Nibble Transmission) is a unique serial interface originally targeted for automotive applications. First adopters are using this interface with sensors used for applications such as throttle position, pressure, mass airflow, and high temperature. The SENT protocol is defined to be output only. For typical safety-critical applications, the sensor data must be output at a constant rate with no bidirectional communications that could cause an interruption. For sensor calibration, a secondary interface is required to communicate with the device. In normal operation, the part is powered up and the transceiver starts transmitting the SENT data. This is very similar to the use model for an analog output with one important difference: SENT is not limited to one data parameter per transmission and can easily report multiple pieces of additional information, such as temperature, production codes, diagnostics, or other secondary data. Figure 1 Example of SENT Interface for High Temperature Sensing SENT Protocol Basic Concepts and Fast Channel Data Transmission The primary data are normally transmitted in what is typically called the “fast channel” with the option to simultaneously send secondary data in the “slow channel.” An example of fast channel transmission is shown in Figure 2. This example shows two 12-bit data words transmitted in each message frame. Many other options are also possible, such as 16 bits for signal 1 and 8 bits for signal 2. Synchronization/ -

Bit, Byte, and Binary

Bit, Byte, and Binary Number of Number of values 2 raised to the power Number of bytes Unit bits 1 2 1 Bit 0 / 1 2 4 2 3 8 3 4 16 4 Nibble Hexadecimal unit 5 32 5 6 64 6 7 128 7 8 256 8 1 Byte One character 9 512 9 10 1024 10 16 65,536 16 2 Number of bytes 2 raised to the power Unit 1 Byte One character 1024 10 KiloByte (Kb) Small text 1,048,576 20 MegaByte (Mb) A book 1,073,741,824 30 GigaByte (Gb) An large encyclopedia 1,099,511,627,776 40 TeraByte bit: Short for binary digit, the smallest unit of information on a machine. John Tukey, a leading statistician and adviser to five presidents first used the term in 1946. A single bit can hold only one of two values: 0 or 1. More meaningful information is obtained by combining consecutive bits into larger units. For example, a byte is composed of 8 consecutive bits. Computers are sometimes classified by the number of bits they can process at one time or by the number of bits they use to represent addresses. These two values are not always the same, which leads to confusion. For example, classifying a computer as a 32-bit machine might mean that its data registers are 32 bits wide or that it uses 32 bits to identify each address in memory. Whereas larger registers make a computer faster, using more bits for addresses enables a machine to support larger programs. -

CLOSED SYLLABLES Short a 5-8 Short I 9-12 Mix: A, I 13 Short O 14-15 Mix: A, I, O 16-17 Short U 18-20 Short E 21-24 Y As a Vowel 25-26

DRILL BITS I INTRODUCTION Drill Bits Phonics-oriented word lists for teachers If you’re helping some- CAT and FAN, which they may one learn to read, you’re help- have memorized without ing them unlock the connection learning the sounds associated between the printed word and with the letters. the words we speak — the • Teach students that ex- “sound/symbol” connection. ceptions are also predictable, This book is a compila- and there are usually many ex- tion of lists of words which fol- amples of each kind of excep- low the predictable associa- tion. These are called special tions of letters, syllables and categories or special patterns. words to the sounds we use in speaking to each other. HOW THE LISTS ARE ORGANIZED This book does not at- tempt to be a reading program. Word lists are presented Recognizing words and pat- in the order they are taught in terns in sound/symbol associa- many structured, multisensory tions is just one part of read- language programs: ing, though a critical one. This Syllable type 1: Closed book is designed to be used as syllables — short vowel a reference so that you can: sounds (TIN, EX, SPLAT) • Meet individual needs Syllable type 2: Vowel- of students from a wide range consonant-e — long vowel of ages and backgrounds; VAT sounds (BAKE, DRIVE, SCRAPE) and TAX may be more appro- Syllable Type 3: Open priate examples of the short a syllables — long vowel sound sound for some students than (GO, TRI, CU) www.resourceroom.net BITS DRILL INTRODUCTION II Syllable Type 4: r-con- those which do not require the trolled syllables (HARD, PORCH, student to have picked up PERT) common patterns which have Syllable Type 5: conso- not been taught. -

Data Representation

Data Representation Data Representation Chapter Three A major stumbling block many beginners encounter when attempting to learn assembly language is the common use of the binary and hexadecimal numbering systems. Many programmers think that hexadecimal (or hex1) numbers represent absolute proof that God never intended anyone to work in assembly language. While it is true that hexadecimal numbers are a little different from what you may be used to, their advan- tages outweigh their disadvantages by a large margin. Nevertheless, understanding these numbering systems is important because their use simplifies other complex topics including boolean algebra and logic design, signed numeric representation, character codes, and packed data. 3.1 Chapter Overview This chapter discusses several important concepts including the binary and hexadecimal numbering sys- tems, binary data organization (bits, nibbles, bytes, words, and double words), signed and unsigned number- ing systems, arithmetic, logical, shift, and rotate operations on binary values, bit fields and packed data. This is basic material and the remainder of this text depends upon your understanding of these concepts. If you are already familiar with these terms from other courses or study, you should at least skim this material before proceeding to the next chapter. If you are unfamiliar with this material, or only vaguely familiar with it, you should study it carefully before proceeding. All of the material in this chapter is important! Do not skip over any material. In addition to the basic material, this chapter also introduces some new HLA state- ments and HLA Standard Library routines. 3.2 Numbering Systems Most modern computer systems do not represent numeric values using the decimal system. -

Bit Nibble Byte Kilobyte (KB) Megabyte (MB) Gigabyte

Bit A bit is a value of either a 1 or 0 (on or off). Nibble A Nibble is 4 bits. Byte Today, a Byte is 8 bits. 1 character, e.g. "a", is one byte. Kilobyte (KB) A Kilobyte is 1,024 bytes. 2 or 3 paragraphs of text. Megabyte (MB) A Megabyte is 1,048,576 bytes or 1,024 Kilobytes 873 pages of plaintext (1,200 characters) 4 books (200 pages or 240,000 characters) Gigabyte (GB) A Gigabyte is 1,073,741,824 (230) bytes. 1,024 Megabytes, or 1,048,576 Kilobytes. 894,784 pages of plaintext (1,200 characters) 4,473 books (200 pages or 240,000 characters) 640 web pages (with 1.6MB average file size) 341 digital pictures (with 3MB average file size) 256 MP3 audio files (with 4MB average file size) 1 650MB CD Terabyte (TB) A Terabyte is 1,099,511,627,776 (240) bytes, 1,024 Gigabytes, or 1,048,576 Megabytes. 916,259,689 pages of plaintext (1,200 characters) 4,581,298 books (200 pages or 240,000 characters) 655,360 web pages (with 1.6MB average file size) 349,525 digital pictures (with 3MB average file size) 262,144 MP3 audio files (with 4MB average file size) 1,613 650MB CD's 233 4.38GB DVD's 40 25GB Blu-ray discs Petabyte (PB) A Petabyte is 1,125,899,906,842,624 (250) bytes, 1,024 Terabytes, 1,048,576 Gigabytes, or 1,073,741,824 Megabytes. 938,249,922,368 pages of plaintext (1,200 characters) 4,691,249,611 books (200 pages or 240,000 characters) 671,088,640 web pages (with 1.6MB average file size) 357,913,941 digital pictures (with 3MB average file size) 268,435,456 MP3 audio files (with 4MB average file size) 1,651,910 650MB CD's 239,400 4.38GB DVD's 41,943 25GB Blu-ray discs Exabyte (EB) An Exabyte is 1,152,921,504,606,846,976 (260) bytes, 1,024 Petabytes, 1,048,576 Terabytes, 1,073,741,824 Gigabytes, or 1,099,511,627,776 Megabytes. -

A Hextet Refers to a Segment Of

A Hextet Refers To A Segment Of Which Hansel panders so methodologically that Rafe dirk her sedulousness? When Bradford succumbs his tastiness retool not bearishly enough, is Zak royalist? Hansel recant painstakingly if subsacral Zak cream or vouch. A hardware is referred to alternate a quartet or hextet each query four hexadecimal. Araqchi all disputable issues between Iran and Sextet ready World. What aisle the parts of an IPv4 address A Host a Network 2. Quantitative Structure-Property Relationships for the. The cleavage structure with orange points of this command interpreter to qsprs available online library of a client program output from another goal of aesthetics from an old pitch relationships between padlock and? The sextet V George Barris SnakePit dragster is under for sale. The first recording of Ho Bynum's new sextet with guitarist Mary Halvorson. Unfiltered The Tyshawn Sorey Sextet at the Jazz Gallery. 10 things you or know about IPv6 addressing. In resonance theory the resonant sextet number hH k of a benzenoid. Sibelius 7 Reference Guide. The six-part romp leans hard into caricatures to sing of mortality and life's. A percussion instrument fashioned out of short segments of hardwood and used in. Arrangements as defined by the UIL State Direc- tor of Music. A new invariant on hyperbolic Dehn surgery space 1 arXiv. I adore to suggest at least some attention the reasons why the sextet is structured as it. Cosmic Challenge Seyferts Sextet July 2020 Phil Harrington This months. Download PDF ScienceDirect. 40 and 9 are octets and 409 is a hextet since sleep number declare the octet. -

RS-232 Control of the Advantage PMX84

RS-232 Control of the Advantage PMX84 ________________________________________________________________________________________ Biamp Systems, 14130 N.W. Science Park, Portland, Oregon 97229 U.S.A. (503) 641-7287 an affiliate of Rauland-Borg Corp. Introduction This document contains technical information relating to computer control of the Biamp Advantage PMX84 Programmable Matrix Switch. This information is intended for advanced users - in particular for those who wish to develop their own computer programs to control the PMX84. It is assumed that the reader is an experienced programmer and has some familiarity with standard programming practices, binary and hexadecimal numbers, the ASCII character set, asynchronous serial data communications, and RS-232 interfaces. Hexadecimal, ASCII-Hex, and "Pseudo-Hex" Numbers Throughout this document, hexadecimal numbers shall be represented by preceding the number with "0x". For example: the hexadecimal equivalent of the decimal number 255 is 0xFF. Individual ASCII characters, except control characters, will be enclosed in single quotes. For example: the ASCII character 'A' has the hexadecimal value 0x41. The ASCII "carriage return" control character shall be represented as . An ASCII code chart is included with this document for your convenience. When an 8-bit binary data value is being transmitted over a serial data communications link, it is a common practice to transmit the byte as two "ASCII-hex" characters - one character represents the most significant nibble of the data value and the other character represents the least significant nibble (a nibble is 4-bits; half of a byte). Each ASCII-hex character is in the range of '0' thru '9' or 'A' thru 'F' (from the ASCII code chart, 0x30 thru 0x39 or 0x41 thru 0x46).