Brook Trout Salvelinus Fontinalis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flood Study of the Suncook River in Epsom, Pembroke, and Allenstown, New Hampshire, 2009

Prepared in cooperation with the Federal Emergency Management Agency Flood Study of the Suncook River in Epsom, Pembroke, and Allenstown, New Hampshire, 2009 Scientific Investigations Report 2010–5127 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover. Photograph looking downstream at area of Suncook River avulsion, Epsom, New Hampshire. (Photograph taken on June 18, 2008) Flood Study of the Suncook River in Epsom, Pembroke, and Allenstown, New Hampshire, 2009 By Robert H. Flynn Prepared in cooperation with the Federal Emergency Management Agency Scientific Investigations Report 2010–5127 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior KEN SALAZAR, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Marcia K. McNutt, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2010 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment, visit http://www.usgs.gov or call 1-888-ASK-USGS For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod To order this and other USGS information products, visit http://store.usgs.gov Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted materials contained within this report. Suggested citation: Flynn, R.H., 2010, Flood study of the Suncook River in Epsom, Pembroke, and Allenstown, New Hampshire, 2009: U.S. -

Technical Memorandum 84-7 2004 Merrimack River Watershed Fish

Technical Memorandum 84-7 2004 Merrimack River Watershed Fish Population Assessment Robert J. Maietta Jane Ryder Watershed Planning Program Worcester, MA July 2008 CN 179.4 Commonwealth of Massachusetts Executive Office of Environmental Affairs Ian Bowles, Secretary Department of Environmental Protection Laurie Burt, Commissioner Bureau of Resource Protection Glenn Haas, Acting Assistant Commissioner Division of Watershed Management Glenn Haas, Director 1 Introduction Fish population surveys were conducted at sixteen stations in the Merrimack River Watershed in Massachusetts using techniques similar to Rapid Bioassessment Protocol V as described originally by Plafkin et al. (1989) and later by Barbour et al. (1999) (See Figure 1). Standard Operating Procedures are described in Fish Collection Procedures for Evaluation of Resident Fish Populations (MassDEP 2006 CN 75.1). Surveys also included a habitat assessment component modified from that described in Barbour et al (1999). Methods Fish populations in the Merrimack River watershed were sampled during August and September of 2004 by electrofishing using a Smith Root Model 12 battery powered backpack electrofisher. A reach of between 80m and 100m was sampled by passing a pole-mounted anode ring, side to side through the stream channel and in and around likely fish holding cover. All fish shocked were netted and held in buckets. Sampling proceeded from an obstruction or constriction, upstream to an endpoint at another obstruction or constriction such as a waterfall or shallow riffle. Following completion of a sampling run, all fish were identified to species, measured, and released. Results of the fish population surveys can be found in Table 1. It should be noted that young-of-the-year (yoy) fish from most species (with the exception of salmonids) are not targeted for collection. -

Tm-81-4 Nashua River Watershed Dwm Year 2003

Technical Memorandum - TM-81-4 NASHUA RIVER WATERSHED DWM YEAR 2003 WATER QUALITY MONITORING DATA - RIVERS DWM Control Number: CN 107.2 Prepared By: Susan Connors December 2005 Commonwealth of Massachusetts Executive Office of Environmental Affairs Stephen R. Pritchard, Secretary Massachusetts Department Of Environmental Protection Robert W. Golledge, Jr., Commissioner Bureau of Resource Protection Glenn Haas, Acting Assistant Commissioner Division of Watershed Management Glenn Haas, Director Table of Contents Introduction.................................................................................................................................................... 3 Table 1. MassDEP DWM 2003 Nashua River Watershed Water Quality Station Locations and Parameters............................................................................................................................. 3 Figure 1. MassDEP DWM 2003 Nashua River Watershed Water Quality Station Locations............... 5 Objectives...................................................................................................................................................... 6 Methods......................................................................................................................................................... 6 Station Observations..................................................................................................................................... 7 Survey Conditions ...................................................................................................................................... -

Water Quality

LAWRENCE HYDROELECTRIC PROJECT LIHI APPLICATION ATTACHMENT B WATER QUALITY 314 CMR 4.00: DIVISION OF WATER POLLUTION CONTROL 4.06: continued 314 CMR 4.00 : DIVISION OF WATER POLLUTION CONTROL 4.06: continued TABLE 20 MERRIMACK RIVER BASIN BOUNDARY MILE POINT CLASS QUALIFIERS Merrimack River State line to Pawtucket Dam 49.8 - 40.6 B Warm Water Treated Water Supply CSO Pawtucket Dam to Essex Dam, 40.6 - 29.0 B Warm Water Lawrence Treated Water Supply CSO Essex Dam, Lawrence to 29.0 - 21.9 B Warm Water Little River, Haverhill CSO Little River, Haverhill to 21.9 - 0.0 SB Shellfishing Atlantic Ocean CSO The Basin in the Merrimack River - SA Shellfishing Estuary, Newbury and Newburyport Stony Brook Entire Length 10.3 - 0.0 B Warm Water Beaver Brook State line to confluence 4.2 - 0.0 B Cold Water with Merrimack River Spicket River State line to confluence 6.4 -0.0 B Warm Water with Merrimack River Little River State line to confluence with 4.3 - 0.0 B Warm Water Merrimack River Cobbler Brook Entire Length 3.7 - 0.0 B Cold Water Powwow River Outlet Lake Gardner to tidal 6.4 - 1.3 B Warm Water portion Tidal portion 1.3 - 0.0 SB Shellfishing Plum Island River North of High Sandy sand bar SA Shellfishing Outstanding Resource Water 1 Water quality standards for Class B and Class SB waters Designated Use/Standard Parameter Support ≥ 5.0 mg/l Inland waters, Class B, Dissolved Oxygen ≥ 60% saturation unless background conditions warm water fishery lower Massachusetts waters, MADEP Temperature ≤ 28.3ºC (83ºF) pH 6.0 to 8.3 S.U. -

A Brief Concord River History

A Brief Concord River History Native Americans Lined by fertile lands and dotted with several good fishing sites, the lower stretch of the Concord River was at one time inhabited by large numbers of Native Americans, well before European settlers made their way across the Atlantic and inland from the coast. Seventeenth-century historian Daniel Goodkin claimed that before contact there were thousands of “Wamesit” making semi-permanent residence on the east side of the Concord, where it met the Merrimack. There they planted corn in the rich alluvial soil, fished “for salmon, shad, lamprey-eels, sturgeon, bass, and diverse others,” and hunted the reportedly abundant game in the surrounding woods. This group was one of two tribes in the area, with another, the “Pawtucket,” at Pawtucket Falls upstream on the Merrimack River. Both belonged to the Pennacook Middlesex Falls Confederacy, and their settlements swelled and shrank in size seasonally, as native visitors came and went with the migration cycles of the anadromous fish. In the 17th century, however, they were killed or run out of the river valley by fearful settlers. By 1726, native rights to the land along the Concord were nonexistent. East Chelmsford & Tewksbury Throughout the eighteenth century, the people of East Chelmsford, now downtown Lowell, were engaged primarily in farming and fishing. Joseph Fletcher and Jonathan Tyler owned the land abutting the Concord River on the west side, some of which they planted or managed as woodlot (see Map 1). On the east side, in Tewksbury, was the “Old Yellow House,” a tavern and hotel where the Wamesit village once stood and where Saints Memorial Medical Center stands today. -

Suncook River – Providing Resiliency Following a Channel-Changing Flood Event

Suncook River – Providing Resiliency Following a Channel-Changing Flood Event New Hampshire Water & Watersheds Conference March 18, 2016 Outline • Study area and avulsion • Project initiation and fundraising • Designs, construction, costs 2 Study Area – Epsom, NH Background HUCKINS MILLS LITTLE SUNCOOK Channel Avulsion RIVER Channel Abandonment LEIGHTON BROOK Migrating SUNCOOK RIVER Knickpoints Aggradation Infrastructure 1992 2011 Rt 4 Bridge Little Suncook River Suncook River Flows Dams Avulsion Site Leighton Brook 2006 – Day after Flood Suncook River Flow Avulsion Site Former Channel USACOE Sand Pit 2006 – Day after Flood Suncook River Flow Suncook River Flow USACOE 2006 – Day after Flood Suncook River Flow Leighton Brook USACOE 2006 – Day after Flood Downstream Deposition USACOE Current Conditions Glacial Lag Deposits Surrounded by Sand Incision and Widening on Leighton Brook Former Channel Elevation Infrastructure Black Hall Rd - Leighton Brook Rt 4 Bridge - Suncook River Buildings – Leighton Brook Project Goals • Protect bridge infrastructure –Rt 4 bridge over Suncook River –Black Hall Rd bridge over Leighton Brook • Control upstream migration of knickpoints on Suncook River and tributaries • Control channel widening Project Initiation and Fundraising 14 Project Initiation and Fundraising 15 Project Initiation and Fundraising 16 Project Initiation and Fundraising 17 2006 • NHDES Geological Survey conducts post-avulsion baseline survey • $8,000 2007 • NHDES and U.S. EPA Section 319 Grant - $24,000 • Non-federal match of $16,000 from -

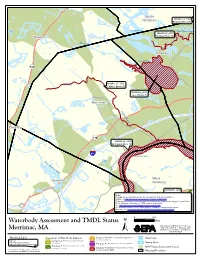

Merrimac, MA Waterbody Assessment, 305(B)/303(D), and Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) Status

South MA84A-28_2008 Hampton Powwow River (5) Lake Tuxbury Pond Pow Wow River MA84A-28_2008 Newton Powwow River (5) Back River Amesbury Lake Attitash 108 MA84A-22_2008 Cobbler Brook (5) MA84002_2008 Lake Attitash (5) Merrimac Cobbler Brook Plaistow 110 MA84A-05_2008 Merrimack River (5) 495 Merrimack River East Meadow River Lake West Haverhill Newbury MA84039_2008 Mill Pond (3) Notes: 1) Adapted from Final Massachusetts Year 2008 Integrated List of Waters; available at http://www.mass.gov/dep/water/resources/08list2.pdf113 Mill 2) Waterbodies shown without an identified category are assigned as Category 3 by definition.Pond 3) For additional information on TMDLs and to view reports, see: http://www.mass.gov/dep/water/resources/tmdls.htm 4) For Massachusetts Surface Water Quality Standards, and waterbody classes and uses, see: http://www.mass.gov/dep/service/regulations/314cmr04.pdf 0 0.5 Waterbody Assessment and TMDL Status Miles Map produced by EPA Region I GIS Center Map Tracker ID 6678, February 25, 2010 Merrimac, MA Data Sources: TeleAtlas, Census Bureau, USGS, MassDEP Waterbody Label Assessment of Waterbody Segment Category 4a: TMDL is completed and approved for Waterbodies one or more pollutants State ID, Category 2: Attaining some uses; other uses Waterbody Name (Category) not assessed Impairment not caused by a pollutant. Swamp/Marsh (TMDL(s) approved for this waterbody) Category 4c: Category 3: Insufficient information to make MS4 Urbanized Areas (2000 Census) assessments for any use. Category 5: Impaired or threatened for one or more See companion table for a listing of pollutants, uses and requiring a TMDL. non-pollutants, and TMDLs for each waterbody Municipal Boundaries. -

The Spicket River & Facella Lot Restoration Project / Rubchinuk

The Spicket River & Facella Lot Restoration Project / Rubchinuk (RFR BWSC 11 NRD 01) Final Project Report Groundwork Lawrence 10/31/2014 Funds from the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection’s Natural Resource Damages (NRD) Program was integral to this project. Soft costs – including survey, design, permitting and project management – as well as construction costs were funded through a grant awarded by the NRD Program. By order of the Suffolk Superior Court entered on March 10, 2010, funds were transferred to the NRD Trust to support community revitalization projects lieu of conducting a project on the former Rubchinuk Landfill site on East Street in Middleton, Massachusetts, a property contaminated by the illegal landfilling of construction and demolition debris. Introduction Groundwork Lawrence received funding from the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection for the implementation of several restoration projects along the Spicket River. This report summarizes the activities undertaken to fulfill the project requirements. The Facella Lot Restoration and Park Project created a new waterfront pocket park along the Spicket River adjacent to a prominent gateway to the city. The program for the park was determined through a two meeting community outreach process with residents and guidance from city staff. The park is an integral component to the regeneration of this part of the city. The Spicket River Bank and Instream Restoration project was developed five years in partnership with the Commonwealth’s Division of Ecological Restoration. Three sites were improved through a range of restoration projects designed to improve the habitat and accessibility along the Spicket River Corridor. These improvements are important to the wildlife living along and in the stream and provide safe locations for the community to safely access the river. -

Provides This File for Download from Its Web Site for the Convenience of Users Only

Disclaimer The Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection (MassDEP) provides this file for download from its Web site for the convenience of users only. Please be aware that the OFFICIAL versions of all state statutes and regulations (and many of the MassDEP policies) are only available through the State Bookstore or from the Secretary of State’s Code of Massachusetts Regulations (CMR) Subscription Service. When downloading regulations and policies from the MassDEP Web site, the copy you receive may be different from the official version for a number of reasons, including but not limited to: • The download may have gone wrong and you may have lost important information. • The document may not print well given your specific software/ hardware setup. • If you translate our documents to another word processing program, it may miss/skip/lose important information. • The file on this Web site may be out-of-date (as hard as we try to keep everything current). If you must know that the version you have is correct and up-to-date, then purchase the document through the state bookstore, the subscription service, and/or contact the appropriate MassDEP program. 314 CMR: DIVISION OF WATER POLLUTION CONTROL 4.06: continued FIGURE LIST OF FIGURES A River Basins and Coastal Drainage Areas 1 Hudson River Basin (formerly Hoosic, Kinderhook and Bashbish River Basins) 2 Housatonic River Basin 3 Farmington River Basin 4 Westfield River Basin 5 Deerfield River Basin 6 Connecticut River Basin 7 Millers River Basin 8 Chicopee River Basin 9 Quinebaug -

Chapter 8 Natural Resources, Open Space & Recreation

Master Plan Chapter 8 Natural Resources, Open Space & Recreation Beaches, marshes, farm fields, pastures, and views of Merrimack River form Newburyport’s heritage landscapes, with many open spaces providing habitat for endangered, rare, and threatened species. More than 20 parks offer residents and visitors the opportunity for wholesome and healthful recreation and lifestyle opportunities, while local regulations and permitting processes seek to encourage the incorporation of green infrastructure in development projects to assist in the provision of clean air, clean water, storm water dispersal and noise attenuation. This chapter provides a structure for ongoing efforts to protect and manage the City’s natural areas, to maintain, expand and improve its parks and recreational spaces, and to continue to enhance management of its green infrastructure. Since the Master Plan of 2001 was complete, the City has made great strides in achieving its goals in the area of Natural Resources, Open Space and Recreation, including: • Reopening the Merrimac River clam flats; • Adding full time Parks Department staff, including a Director and Manager; • Creating the position of Conservation Administrator; • Adopting a Beach Management Plan; • Implementing City-wide wetlands protection and storm water management ordinances and regulations; • Establishing the Open Space Committee, who is instrumental in pursuing land purchases that protect important open space resources, create connections between existing open spaces, recreational areas, the downtown, and -

Archaeological Reconnaissance Survey

ARCHAEOLOGICAL RECONNAISSANCE SURVEY AT THE MILLIE TURNER/BLAKE MILL DAM REMOVAL PROJECT PEPPERELL, MASSACHUSETTS POPULAR REPORT HISTORIC CONTEXT By Barbara Donohue 11 Bright Road Belmont, Massachusetts 02478 For Alexander Hackman Department of Fish and Game Division of Ecological Restoration 251 Causeway Street, Suite 400 Boston, MA 02114 October 29, 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................................................. iii MANAGEMENT SUMMARY ................................................................................................................... iv LIST OF FIGURES ...................................................................................................................................... v LIST OF TABLES ....................................................................................................................................... vi 1.0 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................. 1 2.0 RESEARCH DESIGN ..................................................................................................................... 10 2.1 Statement of Purpose ............................................................................................................ 10 2.2 Documentary Research ......................................................................................................... 10 2.3 Field Reconnaissance -

New England Water Supplies – a Brief History M. Kempe Page 23 Of

New England Water Supplies – A Brief History M. Kempe Chapter 2 – The Search for Water – Growth and Water Source Development Timeline – Water Source Development National and World Events 1929- The Great Baby Boom 1970’s – Growth of Depression Environmentalism Rapid population 1914-1918 1941-1945 Growth of Population growth WWI WWII suburbs growth slows 1880 1900 1920 1940 1960 1980 2000 Many communities augment WPA funds help 1960’s drought original supplies build systems Efficient fixtures Rapid growth of indoor plumbing Post-drought supply shortfalls Era of large water Metering slows projects, dams and Water conservation waste reservoirs instead of Water Events diversions Finding the water has always been one of the main tasks for the water supplier, occasionally a thankless task, even a maligned one. Since the growth of environmentalism in the 1970’s, many people picture a water engineer in terms of John Huston’s shady Noah Cross character from the film “Chinatown”. Most books written about New England water supplies tend to focus on the impacts of reservoir construction, prime examples being “The Day Four Quabbin Towns Died” about Quabbin Reservoir and “The Village of the Dammed” about Saugatuck Reservoir in the Bridgeport system. The loss of one’s home for a reservoir that benefits a distant city is almost certain to create a lifetime of resentment. The fundamental dilemma is that cities exist where they are because of commerce and they drive the economy of the region to everyone’s benefit, even the rural areas that are asked to help provide resources like water. But the cities overwhelm water resources where they exist and have to import water from elsewhere.