The Waterhouse Clock

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Old Supreme Court Chamber (1810-1860)

THE OLD SUPREME COURT CHAMBER 1810–1860 THE OLD SUPREME COURT CHAMBER 1810–1860 Historical Highlights Located on the ground floor of the original north wing of the Capitol Building, this space served as the Senate chamber from 1800 to 1808. It was here that the first joint session of Congress was held in the new capital city of Washington on November 22, 1800, and President Thomas Jeffer- son was inaugurated in 1801 and 1805. Architect Benjamin Henry Latrobe proposed extensive mod- ifications to the area in 1807, which included moving the Senate to the second floor and con- structing a chamber for the Supreme Court of the Working drawing for the Supreme Court Chamber by Benjamin Henry Latrobe, September 26, 1808 United States directly below (in the space previ- ously occupied by the Senate). The Court had been meeting in a small committee room in the north wing since 1801. The Capitol, however, was never intended to be its permanent home; a sepa- rate building for the Court was long discussed, but was not completed until 1935. The work on the Supreme Court chamber did not proceed without difficulties. Cost overruns were a problem, and Congress was slow in appropriating funds to continue the project. In September 1808 construction superintendent John Lenthall was killed when he prematurely removed props sup- porting the chamber’s vaulted ceiling, causing it to collapse. But by August 1809 the massive vault had been rebuilt on an even more ambitious scale. Often likened to an umbrella or a pumpkin, it was a triumph both structurally and aesthetically. -

Thk Northekn Boundary of Massachusetts in Its Relations to New Hampshire

1890.] Northern Boundary of Massachusetts. 11 THK NORTHEKN BOUNDARY OF MASSACHUSETTS IN ITS RELATIONS TO NEW HAMPSHIRE. BY SAMUEL A. GBEBN. THE Colonial Charter of Massachusetts Bay, granted by Charles I., under date of March 4, 1628-9, gave to the Governor and other representatives of the Massachusetts Company, on certain conditions, all the territory lying between an easterly and westerly line running three miles north of any part of the Merrimack River and extending from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific, and a similar paral- lel line running three mileä south of any part of the Charles Kiver. To. be more exact, and to quote the ipsissima verba of the original instrument, the bounds of this tract of land were as follows :— All that parte of Newe England in America which lyes and extendes betweene a great river there comonlie called Monomack riVer, alias Merrimaek river, and a certen other river there called Charles river, being in the bottome of a certen bay there comonlie .called Massachusetts, alias Mat- tachusetts, alias Massatusetts bay : And also all and singu- ler those landes and hereditaments whatsoever, lyeing within the space of three Englishe myles on the south parte of the saide river called Charles river, or of any or every parte thereof : And also all and singuler the landes and heredita- ments whatsoever lyeing and being within the space of three Englishe myles -to the southward of the southermost parte of the said baye called Massachusetts, alias Mattachusetts, alias Massatusetts bay : And also all those lands and hered- itaments whatsoever which lye and be within the space of ' three English myles to the northward of the saide river called Monomack, alias Merry mack, or to be norward of 12 American Antiquarian Soeiety. -

Exploring the Provenance of Elmer Crowell's Decoys

Mar/Apr10_DecoyMag_pgs2-47:Layout 1 6/9/10 9:34 AM Page 30 COVER STORY Connecting the Dots Exploring the provenance of Elmer Crowell’s decoys BY LINDA & G ENE KANGAS ecoy collecting is beginning a noteworthy transition in its youthful history. It is shifting from reliance upon rudimentary information such as who made Dsomething, where and when, to a signifi - cantly more inclusive context that consid - ers the amalgam of social, cultural and economic conditions that influenced de - sign. Understanding those complex dy - namics provides illuminating insights and explains elusive “why” factors. Decoys were often branded with ini - tials that offer clues to a larger story. Two Circa 1905-1910 Crowell hollow goldeneye branded JWW for John Willard Ware. decades ago uncovering comprehensive narratives were challenging; today Internet tioned. Three years later the identical let - of America’s earliest celebrated clockmakers. technology greatly facilitates discovery of ters appeared on an Elmer Crowell gold - When asked about John Ware Willard, the obscure dusty data. Dormant facts can be eneye also sold at auction. Who was museum indicated he had never lived in revived. Connecting the diversity of dots “JWW” and what is known about him? A Grafton. Was the decoy’s inscription true? helps integrate decoys into the spectrum collector’s notation is written on the gold - Verifying that question was essential. In - of North American history. eneye: “John W are Willard, Grafton, Mass.,” vestigating “JWW” led to well-connected peo - For example, in 2006 a Mason factory which is the location of The Willard House ple whose life paths intertwined. -

Samuel Willard: Savior of the Salem Witches

Culhane 1 Samuel Willard: Savior of the Salem Witches By Courtney Culhane Prof. Mary Beth Norton HIST/AMST/FGSS 2090 Culhane 2 It is approximately the first week of August, 1692. He cannot place the exact date, only that it had been roughly nine weeks since his capture on May 30th1. Since then he has lost all track of time, even with the extra daytime freedoms that his wealth and social statues allow him. “Such things did not prevent an accusation,” he mused, “as I am yet a prisoner by eventide, shackles or no, denounced as a witch of all things, by mere children! No matter, the appointed hour has almost arrived. I only pray Mary is prepared…Hark, the signal! It must be the minsters.” “Ye be Phillip English?” a coarse but welcome voice inquiries through the bars, through the darkness; its master bears no candle. “Indeed Reverend.” “Then make haste! The guards are paid off, your wife is waiting. Go now! And ‘if they persecute you in one city, flee to another.’”2 * Purportedly aiding Philip English in his flight from a Boston prison is only one instance of the Reverend Samuel Willard’s substantial personal involvement in the 1692-1693 incidents which American historical tradition has collectively adopted as “The Salem Witch Trials.” Although his participation in numerous areas of the trial proceedings has been definitively confirmed, Willard’s anti-trial “activism” and its consequences still leave curious contemporaries with several questions, the answers to which are necessary for a truly complete understanding of 1 Mary Beth Norton, In the Devil’s Snare: The Salem Witchcraft Crisis of 1692 (New York: Vintage Books 2003) 238. -

The Kaufman Collection

For optimal use of this interactive PDF, please view in Acrobat Reader on a computer/laptop. enter National Gallery of Art > STYLES WIL L IAM AND MARY STYLE (C. 1710 – 1735) QUEEN ANNE STYLE (C. 1735 – 1760) CHIPPENDALE OR ROCOCO STYLE (C. 1750 – 1780) FEDERAL OR EARLY CLASSICAL STYLE (C. 1785 – 1810) LATE CLASSICAL OR EMPIRE STYLE (C. 1805 – 1830) CATO S AL URBAN CENTERS BOT S ON NEWPORT PHILADelPHIA BALTIMORE WILLIAMSBURG CHARLESTON TY PES OF FURNITURE S EATING FURNITURE TABLES DESKS CHESTS LOOKING GLASSES CLOCKS selecteD WORKS GLOSSARY < > < > Masterpieces of American Furniture from the Kaufman Collection, 1700 – 1830 offers visitors to the nation’s capital an unprecedented opportunity to view some of the finest furniture made by colonial and post-revolutionary American artisans. This presentation includes more than one hundred objects from the promised gift, announced in 2010, of the collection formed by Linda H. Kaufman and the late George M. Kaufman. From a rare Massachusetts William and Mary japanned dressing table to Philadelphia’s outstanding rococo expressions and the early and later classical styles of the new federal republic, the Kaufman Collection presents a compendium of American artistic talent over more than a century of history. This promised gift marks the Gallery’s first acquisition of American decorative arts and dramatically transforms the collection, complementing the existing holdings of European decorative arts. The interior of the Kaufmans’ house in Norfolk, Virginia (pages 2 – 3, 5) < > < > The Kaufman Collection represents five decades’ pursuit of the highest quality in American craftsmanship. The Kaufmans made their first acquisition in the late 1950s with the purchase of a chest of drawers to furnish an apartment in Charlottesville when George was completing his MBA at the University of Virginia Darden School of Business. -

Updated: 18 April 2021

Updated: 18 April 2021 ~ 0 ~ z FORWARD This work has been assembled by me from many sources including some related to me verbally. As it says on the cover, they can be tales or myths or legends and possibly sometimes of dubious validity. This has been put together less as a history lesson in some cases, and more as a celebration of what small town life was and still is to some degree. I have decided to not use real names in a few circumstances for various reasons. I don’t consider this a work of fiction for the most part, nor of total fact in a few cases. It was collected mainly for the enjoyment of any former or present Paw Paw resident, or anyone else with ties to the community. Several people have been instrumental in helping this work get into print. The Paw Paw District Library, the Harry Bush family, and most of all Dan Smith, PPHS-63 who has placed it on his pawpawwappaw.com website, and has really spent a lot of time finding candidates for the book, and pictures of them. He also has done a lot to make this work look professional. Thanks to all. Robert “Butch” Hindenach Paw Paw High School Class of ‘57 ~ 1 ~ Table of Contents Forward ................................................................................................................................. 1 Table of Contents ................................................................................................................... 2 Happy Days ........................................................................................................................... -

The Anatomy of Correction: Additions

KU ScholarWorks | http://kuscholarworks.ku.edu Please share your stories about how Open Access to this article benefits you. The Anatomy of Correction: Additions, Cancellations, and Changes in the Documents of the Salem Witchcraft Trials by Peter Grund 2007 This is the author’s accepted manuscript, post peer-review. The original published version can be found at the link below. Peter Grund. 2007. “The Anatomy of Correction: Additions, Cancellations, and Changes in the Documents of the Salem Witchcraft Trials.” Studia Neophilologica 79(1): 3–24. Published version: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00393270701287439 Terms of Use: http://www2.ku.edu/~scholar/docs/license.shtml This work has been made available by the University of Kansas Libraries’ Office of Scholarly Communication and Copyright. Peter Grund. 2007. “The Anatomy of Correction: Additions, Cancellations, and Changes in the Documents of the Salem Witchcraft Trials.” Studia Neophilologica 79(1): 3–24. (accepted manuscript version, post-peer review) The Anatomy of Correction: Additions, Cancellations, and Changes in the Documents of the Salem Witchcraft Trials1 Peter Grund, Uppsala University 1. Introduction The Salem witchcraft trials of 1692 hold a special place in early American history. Though limited in comparison with many European witch persecutions, the Salem trials have reached mythical proportions, particularly in the United States. The some 1,000 extant documents from the trials and, in particular, the pre-trial hearings have been analyzed from various perspectives by (social) historians, anthropologists, biologists, medical doctors, literary scholars, and linguists (see e.g. Rosenthal 1993: 33–36; Mappen 1996; Grund, Kytö and Rissanen 2004: 146). But despite this intense interest in the trials, very little research has been carried out on the actual manuscript documents that have survived from the trials. -

AOC Foundations & Perspectives

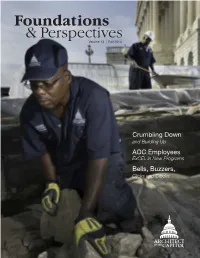

Foundations & Perspectives Volume 13 | Fall 2014 Crumbling Down and Building Up AOC Employees ExCEL in New Programs Bells, Buzzers, Clicks and Clocks Photo by: Dewitt Roseborough Vince Incitto and Cordell Shields review the contents of a storeroom. In This Issue 1 Letter from the Architect 2 AOC Employees ExCEL in New Programs 6 Bells, Buzzers, Clicks and Clocks 12 AOC Bike Commuters: In Their Own Words 16 AOC Moves the House Office Buildings Storerooms 18 Doing Good: Richard Edmonds 20 Dome Update 22 Crumbling Down and Building Up Photo by: Chuck Badal Front Cover: Carroll Rodgers (foreground) and Robert Wallace restore the wall outside the Capitol Senate entrance. Photo by: James Rosenthal View from the access bridge on the West Front that leads to the Capitol Dome Restoration Project. Letter from the Architect The Architect of the Capitol can trace its beginnings to 1791 when President George Washington selected three commissioners to provide proper accommodations for Congress to conduct its business in Washington, D.C. As we carry that mission forward in the work we do today, preservation is key to our success. Over the next few years, stone preservation will be a top priority for the AOC, as nearly every building is encased in stone and almost all are in need of repair (page 22). Soon scaffolding will be visible on buildings around campus including the Capitol Building, Russell Senate Office Building and the Cannon House Office Building to name a few. These critical stone renovation efforts will ensure that the work of Congress can continue for decades to come. -

Text of Lecture Re: Willard Museum 30 Anniversary ©

Text of Lecture Re: Willard Museum 30 th Anniversary © Written from outline used for the lecture Introduction: I had the great honor to be asked to give an address at ceremonies recognizing the thirtieth anniversary of the opening of Willard House and Clock Museum. That was in June of 2001. In July of 2009 Dr. Roger Robinson celebrated his 100 th birthday. He and his late wife Imogene (1901–2004) founded the museum. Both Dr. and Mrs. Robinson attended the ceremonies, and Dr. Robinson gave a fascinating and witty recount of events leading to the opening of the museum. In honor of Dr. Robinson’s centennial the staff of Willard House decided to publish the remarks below. I have written the text from the outline I used at the ceremonies. It fairly closely follows the original remarks as I remember them. I have added some personal footnotes where I think they might add to the text. John C. Losch August, 2009 Good afternoon, Ladies and Gentlemen. This is a wonderful gathering, and it is encouraging to see so many people interested in both the existence and history of the Willard Museum. I think it is appropriate to ask why we are celebrating the Willard Museum. Why not the Smith, or the Robinson Museum? The simple answer is that the Willards were, and remain, the most prominent clockmaking family in the history of American clockmaking. During a period of over 100 years there were numerous Willard family clockmakers. Here are a few reasons why the family has remained prominent for so long. -

Reading in Revolutionary Times: Book Borrowing from the Harvard College Library, 1773-1782

Reading in revolutionary times: Book borrowing from the Harvard College Library, 1773-1782 The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Harvey, Louis-Georges, and Mark Olsen. 1993. Reading in revolutionary times: Book borrowing from the Harvard College Library, 1773-1782. Harvard Library Bulletin, Fall 1993: 57-72. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:42663584 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA The Waterhouse Clock OglesbyPaul and Richard]. Wolfe n the summer of 1950, Mrs. Robert de Wolfe (Mary Ware) Sampson presented Ito the Harvard Medical School an old tall-case (grandfather) clock that she had inherited from her great-grandfather Benjamin Waterhouse. Benjamin Water- house (1754-1846) was a prominent and controversial founding member of the Medical School faculty. He was the first Hersey Professor of the Theory and Prac- tice of Physic, and was especially recognized for his pioneering introduction of smallpox vaccination into the United States in 1800. The door of the clock was distinguished by a round brass plaque reading "The gift of the Honorable Peter Oliver D.C.L. late Chief Justice of the Province of the Massachusetts Bay to Ben- jamin Waterhouse M.D., 1790." Because it was apparent that the decorative finials and fretwork were missing from the top of the case, Dean George Packer Berry authorized Assistant Dean Reginald Fitz to have these restored by a cabinetmaker.' The clock, said to require winding only once or twice a year, was then installed in OGLESBYPAUL is Professor of a comer in the Faculty Room named for the same Benjamin Waterhouse. -

Willard School Improved Timepiece with an Unusual “Patent” Glass by Richard Perlman (PA)

© 2014 National Association of Watch and Clock Collectors, Inc. Reproduction prohibited without written permission. An Early Willard School Improved Timepiece with an Unusual “Patent” Glass by Richard Perlman (PA) rom about 1800 to 1818 Simon Willard, his appren- Co., 18 South 10th Street (between Market and Chestnut F tices, and family members made the new Improved streets), Philadelphia (about 1900 and later) (Figure 2B). Timepiece. During this time they placed various patent Lovell’s shop was near City Hall. He was a merchant with references on their reverse-painted glasses, probably in a repair shop. On Lovell’s label is written: Return to: “J. deference to the Patentee. Rarely was their work signed in T. Vodges Room 127 City Hall.” The monumental Phila- a conventional manner on the dial. Simon Willard’s Pat- delphia City Hall was completed in 1900, taking about 30 ent was from 1802 to 1816. He never placed his name on years to build. the dial of these early examples. Early work made by oth- Research revealed the name was misspelled on the la- ers was nearly identical to Simon Willard’s except for the bel and is actually J. T. Vogdes, whose offi ce was Room reverse-painted “Patent” refer- 127, City Hall. Jesse T. Vogdes was the chief engineer and ence found on their glasses. superintendent of Fairmount Park from 1898 to 1919. Over many years, questions Fairmount Park is the largest inner-city park in the Unit- surrounding the various pat- ed States. His father (1818-1893) and grandfather (1783- ent references found on early 1847) were both Jesse T. -

Führung Durch Das Kapitol Der Vereinigten Staaten

Deutsch > GERMAN Führung durch das Kapitol der Vereinigten Staaten Willkommen im Kapitol der Vereinigten Staaten von Amerika! Allgemeine Informationen über die Führung • Führungen durch das historische Kapitol beginnen des Kinosaals (Orientation Theater), in dem der mit einem kurzen Einführungsfilm. Die Führung Einführungsfilm gezeigt wird. wird auf Englisch durchgeführt. Kopfhörer mit • Wir hoffen sehr, dass Sie sich während der Übersetzungen des Films in andere Sprachen sind Führung am Anblick der Statuen und Gemälde jedoch an den Informationsschaltern auf der Nord- erfreuen können. Sie werden jedoch höflichst und Südseite (North and South Information Desks) darum gebeten, diese bitte nicht zu berühren. erhältlich. • Bitte setzen Sie sich nicht auf den Fußboden; • Um die Sicherheit des Kapitols zu gewährleisten, im Besucherzentrum (Capitol Visitor Center) stehen ist es unbedingt erforderlich, dass Sie Ihnen eine Reihe von Bänken zur Verfügung. während der gesamten Führung bei dem Ihnen • Sollten Sie aus einem beliebigen Grund ärztliche zugeteilten Touristenführer bleiben. Hilfe benötigen, informieren Sie bitte sofort • Während der Führung stehen keine öffentlichen Ihren Touristenführer oder einen Beamten der Toiletten zur Verfügung. Die Möglichkeit der U.S. Capitol Police. Toilettennutzung besteht jedoch vor Betreten Die große weiße Abdeckplane, die von der Decke der Rotunde herunterhängt, dient der Restaurierung der Kapitolkuppel. Die Kuppel, die vor mehr als 150 Jahren aus Gusseisen errichtet wurde, weist inzwischen 1.300 Risse auf und wird daher zurzeit restauriert. Während der Restaurierungsarbeiten dient die Abdeckplane dem Schutz der Besucher des Kapitols vor losem oder herabfallendem Baumaterial. National Statuary Hall Die National Statuary Hall, auch „Old Hall of the House“ genannt, ist ein großer, zweistöckiger, halbrunder Raum südlich der Rotunde.