Physical Geography Historical Changes of a Major Juncture: Lower

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Atchafalaya Basin

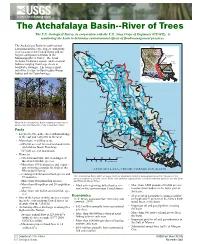

7KH$WFKDIDOD\D%DVLQ5LYHURI7UHHV The U.S. Geological Survey, in cooperation with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE), is monitoring the basin to determine environmental effects of flood-management practices. The Atchafalaya Basin in south-central Louisiana includes the largest contiguous river swamp in the United States and the largest contiguous wetlands in the Mississippi River Valley. The basin includes 10 distinct aquatic and terrestrial habitats ranging from large rivers to backwater swamps. The basin is most noted for its cypress-tupelo gum swamp habitat and its Cajun heritage. Water in the Atchafalaya Basin originates from one or more of the distributaries of the Atchafalaya River. Facts • Located between the cities of Baton Rouge to the east and Lafayette to the west. • More than 1.4 million acres: --885,000 acres of forested wetlands in the Atchafalaya Basin Floodway. --517,000 acres of marshland. • Home to: --9 Federal and State listed endangered/ threatened wildlife species. --More than 170 bird species and impor- tant wintering grounds for birds of the Mississippi Flyway. --6 endangered/threatened bird species and The Atchafalaya Basin offers an opportunity to implement adaptive management practices because of the 29 rookeries. general support of private, local, State, and national organizations and governmental agencies for the State --More than 40 mammalian species. and Federal Master Plans. --More than 40 reptilian and 20 amphibian • Most active-growing delta (land accre- • More than 1,000 pounds of finfish per acre species. tion) in the conterminous United States. in some water bodies in the lower part of --More than 100 finfish and shellfish spe- the basin. -

Atchafalaya National Wildlife Refuge Managed As Part of Sherburne Complex

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Atchafalaya National Wildlife Refuge Managed as part of Sherburne Complex Tom Carlisle This basin contains over one-half million acres of hardwood swamps, lakes and bayous, and is larger than the vast Okefenokee Swamp of Georgia and Florida. It is an immense This blue goose, natural floodplain of the Atchafalaya designed by J.N. River, which flows for 140 miles south “Ding” Darling, from its parting from the Mississippi has become the River to the Gulf of Mexico. symbol of the National Wildlife The fish and wildlife resources Refuge System. of the Atchafalaya River Basin are exceptional. The basin’s dense bottomland hardwoods, cypress- tupelo swamps, overflow lakes, and meandering bayous provide a tremendous diversity of habitat for many species of fish and wildlife. Ecologists rank the basin as one of the most productive wildlife areas in North America. The basin also supports an extremely productive sport and commercial fishery, and provides unique recreational opportunities to hundreds of thousands of Americans each year. Wildlife Every year, thousands of migratory waterfowl winter in the overflow swamps and lakes of the basin, located at the southern end of the great Mississippi Flyway. The lakes of the lower basin support one of the largest wintering concentrations of canvasbacks in Louisiana. The basin’s wooded wetlands also provide vital nesting habitat for wood ducks, and support the nation’s largest concentration of American America’s Great River Swamp woodcock. More than 300 species of Deep in the heart of Cajun Country, resident and migratory birds use the basin, including a large assortment at the southern end of the Lower of diving and wading birds such as egrets, herons, ibises, and anhingas. -

Prehistoric Settlements of Coastal Louisiana. William Grant Mcintire Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1954 Prehistoric Settlements of Coastal Louisiana. William Grant Mcintire Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Mcintire, William Grant, "Prehistoric Settlements of Coastal Louisiana." (1954). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 8099. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/8099 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HjEHisroaic smm&ws in coastal Louisiana A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Geography and Anthropology by William Grant MeIntire B. S., Brigham Young University, 195>G June, X9$k UMI Number: DP69477 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI DP69477 Published by ProQuest LLC (2015). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code ProQuest: ProQuest LLC. -

Multi-Use Management in the Atchafalaya River Basin: Research at the Confluence of Public Policy and Ecosystem Science

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Reports IGERT 2013 Multi-Use Management in the Atchafalaya River Basin: Research at the Confluence of Public Policy and Ecosystem Science Micah Bennett Southern Illinois University Carbondale Kelley Fritz Southern Illinois University Carbondale Anne Hayden-Lesmeister Southern Illinois University Carbondale Justin Kozak Southern Illinois University Carbondale Aaron Nickolotsky Southern Illinois University Carbondale Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/igert_reports A report in fulfillment of the NSF IGERT Program requirements. This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. 0903510. Recommended Citation Bennett, Micah; Fritz, Kelley; Hayden-Lesmeister, Anne; Kozak, Justin; and Nickolotsky, Aaron, "Multi-Use Management in the Atchafalaya River Basin: Research at the Confluence of Public Policy and Ecosystem Science" (2013). Reports. Paper 2. http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/igert_reports/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the IGERT at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Reports by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MULTI-USE MANAGEMENT IN THE ATCHAFALAYA RIVER BASIN: RESEARCH AT THE CONFLUENCE OF PUBLIC POLICY AND ECOSYSTEM SCIENCE BY MICAH BENNETT, KELLEY FRITZ, ANNE HAYDEN-LESMEISTER, JUSTIN KOZAK, AND AARON NICKOLOTSKY SOUTHERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY CARBONDALE NSF IGERT PROGRAM IN WATERSHED SCIENCE AND POLICY A report -

International Steam Tables - Properties of Water and Steam Based on the Industrial Formulation IAPWS-IF97

International Steam Tables - Properties of Water and Steam based on the Industrial Formulation IAPWS-IF97 Tables, Algorithms, Diagrams, and CD-ROM Electronic Steam Tables - All of the equations of IAPWS-IF97 including a complete set of supplementary backward equations for fast calculations of heat cycles, boilers, and steam turbines Bearbeitet von Wolfgang Wagner, Hans-Joachim Kretzschmar Neuausgabe 2007. Buch. xix, 391 S. ISBN 978 3 540 21419 9 Format (B x L): 21 x 27,9 cm Weitere Fachgebiete > Geologie, Geographie, Klima, Umwelt > Umweltwissenschaften > Ökologie, Allgemeines Zu Inhaltsverzeichnis schnell und portofrei erhältlich bei Die Online-Fachbuchhandlung beck-shop.de ist spezialisiert auf Fachbücher, insbesondere Recht, Steuern und Wirtschaft. Im Sortiment finden Sie alle Medien (Bücher, Zeitschriften, CDs, eBooks, etc.) aller Verlage. Ergänzt wird das Programm durch Services wie Neuerscheinungsdienst oder Zusammenstellungen von Büchern zu Sonderpreisen. Der Shop führt mehr als 8 Millionen Produkte. Preface to the Second Edition The international research regarding the thermophysical properties of water and steam has been coordinated by the International Association for the Properties of Water and Steam (IAPWS). IAPWS is responsible for the international standards for thermophysical properties. These standards and recommendations are given in the form of releases, guidelines, and advisory notes. One of the most important standards in this sense is the formulation for the thermodynamic properties of water and steam for industrial use. In 1997, IAPWS adopted the “IAPWS Industrial Formulation 1997 for the Thermodynamic Properties of Water and Steam” for industrial use, called IAPWS-IF97 for short. The formulation IAPWS-IF97 replaced the previous industrial formulation IFC-67 published in 1967. -

Overview of the Mississippi River & Tributaries (Mr&T)

1 OVERVIEW OF THE MISSISSIPPI RIVER & TRIBUTARIES (MR&T) - ATCHAFALAYA BASIN PROJECT 237 217 200 80 252 237 217 200 119 174 237 217 200 27 .59 255 0 163 131 239 110 112 62 102 130 Port255 Of0 Morgan163 City132 –65 Stakeholder135 92 Meeting102 56 120 255 0 163 122 53 120 56 130 48 111 Durund Elzey Assistance Deputy District Engineer (ADPM) US Army Corps of Engineers New Orleans District 11 February 2019 2 TOPICS OF DISCUSSION • Passing the MR&T Project Design Flood • The Jadwin Plan • The Morganza Floodway • The Old River Control Complex • MR&T Atchafalaya Basin Flood Control Project • Atchafalaya Basin Levee Construction • Atchafalaya Basin O&M • Atchafalaya River Dredging • The Atchafalaya Basin Floodway System (ABFS) Project • Sedimentation Issues • Path Forward 3 THE FLOOD OF 1927 Flood Control Act of 1928 4 and the Jadwin Plan The Morganza Floodway 5 6 Old River Control Structures Authorized 1973 Flood . The Low Sill Control Structure was undermined and the Wing Wall failed . The Old River Overbank Control Structure and the Morganza Control Structure were opened to relieve stress on the Low Sill Control Structure . Due to severe damage to the Low Sill Control Structure, USACE recommended construction of the Auxiliary Control Structure, which was completed in 1986 Morganza Control Structure Operated for First Time View of Old River Control Complex Old River Lock Auxiliary Control Structure Low Sill Control Structure Overbank Control Structure S.A. Murray Hydro 9 The Flood of 2011 10 Extent of 1927 Flood (in Blue) Versus 2011 Flood (in Green) Passing the Project Design Flood 11 The MR&T Atchafalaya Basin Project The MR&T Atchafalaya Basin Project Major Components • 451 Miles of Levees and Floodwalls • 4 Navigation Locks . -

Water: Economics and Policy 2021 – ECI Teaching Module

Water: Economics and Policy By Brian Roach, Anne-Marie Codur and Jonathan M. Harris An ECI Teaching Module on Social and Environmental Issues in Economics Global Development Policy Center Boston University 53 Bay State Road Boston, MA 02155 bu.edu/gdp WATER: ECONOMICS AND POLICY Economics in Context Initiative, Global Development Policy Center, Boston University, 2021. Permission is hereby granted for instructors to copy this module for instructional purposes. Suggested citation: Roach, Brian, Anne-Marie Codur, and Jonathan M. Harris. 2021. “Water: Economics and Policy.” An ECI Teaching Module on Social and Economic Issues, Economics in Context Initiative, Global Development Policy Center, Boston University. Students may also download the module directly from: http://www.bu.edu/eci/education-materials/teaching-modules/ Comments and feedback from course use are welcomed: Economics in Context Initiative Global Development Policy Center Boston University 53 Bay State Road Boston, MA 02215 http://www.bu.edu/eci/ Email: [email protected] NOTE – terms denoted in bold face are defined in the KEY TERMS AND CONCEPTS section at the end of the module. 1 WATER: ECONOMICS AND POLICY TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. GLOBAL SUPPLY AND DEMAND FOR WATER.................................................... 3 1.1 Water Demand, Virtual Water, and Water Footprint ................................................. 8 1.2 Virtual Water Trade ................................................................................................. 11 1.3 Water Footprint the Future of Water: -

Nutrient Delivery from the Mississippi River to the Gulf of Mexico And

the entire landscape must be considered if hydrologic and water quality models are doi:10.2489/jswc.69.1.26 used to predict the delivery of sediment and nutrients. Similarly, the contribution of other sources (including noncultivated lands, urban areas, forests, and the direct discharge Nutrient delivery from the Mississippi of waste water to streams and rivers) should be accounted for. In addition, processes River to the Gulf of Mexico and effects of occurring in streams, lakes, and reservoirs affect the fate of pollutants as they are trans- cropland conservation ported through the system and should also be included. M.J. White, C. Santhi, N. Kannan, J.G. Arnold, D. Harmel, L. Norfleet, P. Allen, M. DiLuzio, X. Comprehensive water quality simulation Wang, J. Atwood, E. Haney, and M. Vaughn Johnson at the scale of the Mississippi River Basin (MRB, 3,220,000 km2 [1,240,000 mi2]) is Abstract: Excessive nutrients transported from the Mississippi River Basin (MRB) have cre- a difficult task; thus, only a few modeling ated a hypoxic zone within the Gulf of Mexico, with numerous negative ecological effects. efforts at that scale have been conducted Copyright © 2014 Soil and Water Conservation Society. All rights reserved. Furthermore, federal expenditures on agricultural conservation practices have received to date. The contiguous United States was Journal of Soil and Water Conservation intense scrutiny in recent years. Partly driven by these factors, the USDA Conservation simulated by Srinivasan et al. (1998) in the Effects Assessment Project (CEAP) recently completed a comprehensive evaluation of nutri- Hydrologic Unit Model for the United ent sources and delivery to the Gulf. -

Addressing the Impact of Gavins Point Dam on the Lowermost~1400 Kilometers of the Missouri River

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 2016 Addressing The mpI act Of Gavins Point Dam On The Lowermost~1400 Kilometers Of The iM ssouri River Gregory Leaphart University of South Carolina Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the Civil Engineering Commons Recommended Citation Leaphart, G.(2016). Addressing The Impact Of Gavins Point Dam On The Lowermost~1400 Kilometers Of The Missouri River. (Master's thesis). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/3919 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ADDRESSING THE IMPACT OF GAVINS POINT DAM ON THE LOWERMOST ~1400 KILOMETERS OF THE MISSOURI RIVER by Gregory Leaphart Bachelor of Science Clemson University, 2013 ___________________________________________ Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Science in Civil Engineering College of Engineering and Computing University of South Carolina 2016 Accepted by: Enrica Viparelli, Director of Thesis Jasim Imran, Reader Seydehzahra Zhara Samadi, Reader Cheryl L. Addy, Vice Provost and Dean of The Graduate School © Copyright by Gregory Leaphart, 2016 All Rights Reserved ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Appreciation is extended toward Dr. Enrica Viparelli for her guidance and direction throughout the duration of graduate school and the thesis process. Gratitude is also given to Zeyad Sulaiman for his assistance throughout the duration of the thesis process. Hybrid Engineering, Inc. and CDM Smith are to be thanked for the extension of employment in spite of the time commitment required by graduate school and the thesis process. -

Water Withdrawal and Conservation Practices

Water Withdrawal And Conservation Practices Prepared for Michigan Chamber of Commerce February 2008 Submitted by Barr Engineering Company Table of Contents 1. Introduction 1 Foreword ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Background and Purpose ............................................................................................................. 1 2. Position Statement 3 Water Efficiency – Resource Sustainability – Conservation Management................................... 3 Our Goal Statement ..................................................................................................................... 3 Our Objectives............................................................................................................................. 3 3. Generally Accepted Management Practices for Water Efficiency and Conservation 4 Communication ........................................................................................................................... 4 Process......................................................................................................................................... 4 Washrooms.................................................................................................................................. 5 Landscaping................................................................................................................................. 5 Appendix A – Links to Websites 6 Appendix -

Published by Ministry of Energy and Water Development February 2010

- NATIONAL WATER POLICY Published by Ministry of Energy and Water Development February 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD ......................................................................................................................... i ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ....................................................................................................... ii ACRONYMS .........................................................................................................................iii WORKING DEFINITIONS ....................................................................................................iv 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Water Resources Availability .............................................................................................. 1 1.2 Rainfall Situation................................................................................................................... 2 1.3 Surface Water Situation ...................................................................................................... 3 1.4 Groundwater Situation ......................................................................................................... 3 1.5 Environmental Management .............................................................................................. 4 1.6 Historical Background .......................................................................................................... 5 2. SITUATION -

Mississippi River

Mississippi River In 2011 the lower Mississippi River carried the greatest volume of floodwaters ever recorded, exceeding the his- toric flood of 1927. In that earlier flood, considered the most destructive river flood in the history of the United States, levees were breached or overtopped in 145 loca- tions, 70,000 km2 were inundated, and 700,000 people were displaced for weeks to months. Officially hundreds of people died but more likely thousands of rural resi- dents were killed (Barry 1997). The flood exposed two primary limitations to river and floodplain management of the time. First, flood manage- ment relied excessively on levees (the “levees-only” ap- proach) which presumed that nearly the entire floodplain could be disconnected from river floods. Second, flood- plain and river management was uncoordinated. In response to the flood, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers developed the Mississippi Rivers and Tributaries Project (MR&T). The MR&T coordinated levee placement and design, dam development and operations, floodplain management and navigation for the lower Mississippi Riv- er basin, including several major tributaries (U.S. Army Corps of Engineers 2008). In addition to replacing a piecemeal approach to river management with a comprehensive system approach, the MR&T also moved floodplain management away from the “levees only” approach and included floodplain storage and conveyance as critical components of flood-risk man- Figure 1. The Mississippi River and Tributaries Project. Floodways agement. Four floodways were designated, portions of the are circled in red. (US Army Corps of Engineers) historic floodplain that would reconnect to the river and convey floodwaters during the highest floods (Figure 1).