The Management of the Mississippi River System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Upper Mississippi River Conservation Opportunity Area Wildlife Action Plan

Version 3 Summer 2012 UPPER MISSISSIPPI RIVER CONSERVATION OPPORTUNITY AREA WILDLIFE ACTION PLAN Daniel Moorehouse Mississippi River Pool 19 A cooperative, inter-agency partnership for the implementation of the Illinois Wildlife Action Plan in the Upper Mississippi River Conservation Opportunity Area Prepared by: Angella Moorehouse Illinois Nature Preserves Commission Elliot Brinkman Prairie Rivers Network We gratefully acknowledge the Grand Victoria Foundation's financial support for the preparation of this plan. Table of Contents List of Figures .............................................................................................................................. ii Acronym List .............................................................................................................................. iii I. Introduction to Conservation Opportunity Areas ....................................................................1 II. Upper Mississippi River COA ..................................................................................................3 COAs Embedded within Upper Mississippi River COA ..............................................................5 III. Plan Organization .................................................................................................................7 IV. Vision Statement ..................................................................................................................8 V. Climate Change .......................................................................................................................9 -

Geomorphic Classification of Rivers

9.36 Geomorphic Classification of Rivers JM Buffington, U.S. Forest Service, Boise, ID, USA DR Montgomery, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA Published by Elsevier Inc. 9.36.1 Introduction 730 9.36.2 Purpose of Classification 730 9.36.3 Types of Channel Classification 731 9.36.3.1 Stream Order 731 9.36.3.2 Process Domains 732 9.36.3.3 Channel Pattern 732 9.36.3.4 Channel–Floodplain Interactions 735 9.36.3.5 Bed Material and Mobility 737 9.36.3.6 Channel Units 739 9.36.3.7 Hierarchical Classifications 739 9.36.3.8 Statistical Classifications 745 9.36.4 Use and Compatibility of Channel Classifications 745 9.36.5 The Rise and Fall of Classifications: Why Are Some Channel Classifications More Used Than Others? 747 9.36.6 Future Needs and Directions 753 9.36.6.1 Standardization and Sample Size 753 9.36.6.2 Remote Sensing 754 9.36.7 Conclusion 755 Acknowledgements 756 References 756 Appendix 762 9.36.1 Introduction 9.36.2 Purpose of Classification Over the last several decades, environmental legislation and a A basic tenet in geomorphology is that ‘form implies process.’As growing awareness of historical human disturbance to rivers such, numerous geomorphic classifications have been de- worldwide (Schumm, 1977; Collins et al., 2003; Surian and veloped for landscapes (Davis, 1899), hillslopes (Varnes, 1958), Rinaldi, 2003; Nilsson et al., 2005; Chin, 2006; Walter and and rivers (Section 9.36.3). The form–process paradigm is a Merritts, 2008) have fostered unprecedented collaboration potentially powerful tool for conducting quantitative geo- among scientists, land managers, and stakeholders to better morphic investigations. -

Stream Restoration, a Natural Channel Design

Stream Restoration Prep8AICI by the North Carolina Stream Restonltlon Institute and North Carolina Sea Grant INC STATE UNIVERSITY I North Carolina State University and North Carolina A&T State University commit themselves to positive action to secure equal opportunity regardless of race, color, creed, national origin, religion, sex, age or disability. In addition, the two Universities welcome all persons without regard to sexual orientation. Contents Introduction to Fluvial Processes 1 Stream Assessment and Survey Procedures 2 Rosgen Stream-Classification Systems/ Channel Assessment and Validation Procedures 3 Bankfull Verification and Gage Station Analyses 4 Priority Options for Restoring Incised Streams 5 Reference Reach Survey 6 Design Procedures 7 Structures 8 Vegetation Stabilization and Riparian-Buffer Re-establishment 9 Erosion and Sediment-Control Plan 10 Flood Studies 11 Restoration Evaluation and Monitoring 12 References and Resources 13 Appendices Preface Streams and rivers serve many purposes, including water supply, The authors would like to thank the following people for reviewing wildlife habitat, energy generation, transportation and recreation. the document: A stream is a dynamic, complex system that includes not only Micky Clemmons the active channel but also the floodplain and the vegetation Rockie English, Ph.D. along its edges. A natural stream system remains stable while Chris Estes transporting a wide range of flows and sediment produced in its Angela Jessup, P.E. watershed, maintaining a state of "dynamic equilibrium." When Joseph Mickey changes to the channel, floodplain, vegetation, flow or sediment David Penrose supply significantly affect this equilibrium, the stream may Todd St. John become unstable and start adjusting toward a new equilibrium state. -

Is Hydrology Kinematic?

HYDROLOGICAL PROCESSES Hydrol. Process. 16, 667–716 (2002) DOI: 10.1002/hyp.306 Is hydrology kinematic? V. P. Singh* Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA 70803-6405, USA Abstract: A wide range of phenomena, natural as well as man-made, in physical, chemical and biological hydrology exhibit characteristics similar to those of kinematic waves. The question we ask is: can these phenomena be described using the theory of kinematic waves? Since the range of phenomena is wide, another question we ask is: how prevalent are kinematic waves? If they are widely pervasive, does that mean hydrology is kinematic or close to it? This paper addresses these issues, which are perceived to be fundamental to advancing the state-of-the-art of water science and engineering. Copyright 2002 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. KEY WORDS biological hydrology; chemical hydrology; physical hydrology; kinematic wave theory; kinematics; flux laws INTRODUCTION There is a wide range of natural and man-made physical, chemical and biological flow phenomena that exhibit wave characteristics. The term ‘wave’ implies a disturbance travelling upstream, downstream or remaining stationary. We can visualize a water wave propagating where the water itself stays very much where it was before the wave was produced. We witness other waves which travel as well, such as heat waves, pressure waves, sound waves, etc. There is obviously the motion of matter, but there can also be the motion of form and other properties of the matter. The flow phenomena, according to the nature of particles composing them, can be distinguished into two categories: (1) flows of discrete noncoherent particles and (2) flows of continuous coherent particles. -

Lower Mississippi River Basin Planning Scoping Document

2001 Basin Plan Scoping Document Balmm Basin Alliance for the Lower Mississippi In Minnesota Lower Mississippi River Basin Planning Scoping Document June 2001 balmm Basin Alliance for the Lower Mississippi in Minnesota About BALMM A locally led alliance of land and water resource agencies has formed in order to coordinate efforts to protect and improve water quality in the Lower Mississippi River Basin. The Basin Alliance for the Lower Mississippi in Minnesota (BALMM) covers both the Lower Mississippi and Cedar River Basins, and includes a wide range of local, state and federal resource agencies. Members of the Alliance include Soil and Water Conservation District managers, county water planners, and regional staff of the Board of Soil and Water Resources, Pollution Control Agency, Natural Resources Conservation Service, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, University of Minnesota Extension, Department of Natural Resources, Mississippi River Citizen Commission, the Southeastern Minnesota Water Resources Board, the Cannon River Watershed Partnership, and others. BALMM meetings are open to all interested individuals and organizations. Existing staff from county and state agencies provide administrative, logistical and planning support. These include: Kevin Scheidecker, Fillmore SWCD, Chair; Norman Senjem, MPCA-Rochester, Basin Coordinator; Clarence Anderson, Rice SWCD, Area 7 MASWCD Liaison; Bea Hoffmann, SE Minnesota Water Resources Board Liaison. This Basin Plan Scoping Document is the fruit of a year-long effort by participants in BALMM. Environmental Goals, Geographic Management Strategies and Land-Use Strategies were developed by either individual BALMM members or strategy teams. An effort was made to involve those who will implement the strategies in developing them. -

Lower Mississippi River Basin

1 Response to RFI for Long-Term Agro-ecosystem Research (LTAR) Network 2012 Lower Mississippi River Basin Abstract: The Lower Mississippi River Basin (LMRB) is a key 2-digit HUC watershed comprised of highly productive and diverse agricultural and natural ecosystems lying along the lower reaches of the largest river in North America. The alluvial plain within the LMRB is one of the most productive agricultural regions in the United States, particularly for rice, cotton, corn and soybeans. The LMRB accounts, for example, for a quarter of total U.S. cotton and two-thirds of total U.S. rice production. The 7.1 million irrigated acres of the LMRB cover a larger percentage (>10%) of the entire land area of the basin than for any other two-digit HUC in the country and the basin is second only to California in total groundwater pumped for irrigation. The LMRB is therefore one of the most intensively developed regions for irrigated agriculture in the country. This region is the hydrologic gateway to the Gulf of Mexico and thus links the agricultural practices of the LMRB and the runoff and sediment/nutrient loads from the Upper Mississippi, Missouri, and Ohio basins with the Gulf ecosystem. While the natural and agricultural ecosystems of the LMRB are each of national significance, they are also intimately inter-connected, for example, the intensive agricultural irrigation along the alluvial plain has resulted in rapidly declining water tables. Changes in stream hydrology due to declining base-flow combined with the water quality impacts of agriculture make the LMRB a tightly-coupled agro-ecosystem with national significance and thus an ideal addition to the LTAR network. -

River Engineering John Fenton

River Engineering John Fenton Institute of Hydraulic Engineering and Water Resources Management Vienna University of Technology, Karlsplatz 13/222, 1040 Vienna, Austria URL: http://johndfenton.com/ URL: mailto:[email protected] 1. Introduction 1.1 The nature of what we will and will not do – illuminated by some aphorisms and some people “There is nothing so practical as a good theory” – stated in 1951 by Kurt Lewin (D-USA, 1890-1947): this is essentially the guiding principle behind these lectures. We want to solve practical problems, both in professional practice and research, and to do this it is a big help to have a theoretical understanding and a framework. “The purpose of computing is insight, not numbers” – the motto of a 1973 book on numerical methods for practical use by the mathematician Richard Hamming (USA, 1915-1998). That statement has excited the opinions of many people (search any three of the words in the Internet!). However, numbers are often important in engineering, whether for design, control, or other aspects of the practical world. A characteristic of many engineers, however, is that they are often blinded by the numbers, and do not seek the physical understanding that can be a valuable addition to the numbers. In this course we are not going to deal with many numbers. Instead we will deal with the methods by which numbers could be obtained in practice, and will try to obtain insight into those methods. Hence we might paraphrase simply: "The purpose of this course is insight into the behaviour of rivers; with that insight, numbers can be often be obtained more simply and reliably". -

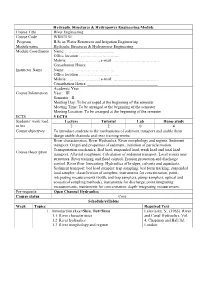

Hydraulic Structures & Hydropower Engineering Module Course Title

Hydraulic Structures & Hydropower Engineering Module Course Title River Engineering Course Code WRIE3151 Program B.Sc in Water Resources and Irrigation Engineering Module name Hydraulic Structures & Hydropower Engineering Module Coordinator Name: . …………………………….. Office location . ……………………….. Mobile: . ………………….; e-mail: ……………………………. Consultation Hours: Instructor Name Name: . …………………………….. Office location . ……………………….. Mobile: . ………………….; e-mail: ……………………………. Consultation Hours: Academic Year Course Information Year: III Semester : II Meeting Day: To be arranged at the beginning of the semester Meeting Time: To be arranged at the beginning of the semester Meeting Location: To be arranged at the beginning of the semester ECTS 5 ECTS Students’ work load Lecture Tutorial Lab Home study in hrs 2 2 0 4 Course objectives To introduce students to the mechanisms of sediment transport and enable them design stable channels and river training works. River characteristics. River Hydraulics. River morphology and regime. Sediment transport: Origin and properties of sediment, initiation of particle motion. Transportation mechanics, Bed load, suspended load, wash load and total load Course Description transport. Alluvial roughness. Calculation of sediment transport. Local scours near structures. River training and flood control. Erosion protection and discharge control. River flow forecasting. Hydraulics of bridges, culverts and aqueducts. Sediment transport: bed load sampler: trap sampling, bed form tracking; suspended load sampler: classification of samplers, instruments for concentration, point- integrating measurements (bottle and trap samplers, pump-samplers, optical and acoustical sampling methods), instruments for discharge, point integrating measurements, instruments for concentration, depth-integrating measurement. Pre-requisite Open Channel Hydraulics Course status Core Schedule/syllabus Week Topics Required Text 1. Introduction (Lec=5hrs, Tut=5hrs) Lelaviasky, S., (1965). River 1.1 River characteristics and Canal Hydraulics, Vol. -

Restoring America's Greatest River Plan

RESTORING AMERICA’S GREATEST RIVER A HABITAT RESTORATION PLAN FOR THE LOWER MISSISSIPPI RIVER LOWER MISSISSIPPI RIVER CONSERVATION COMMITTEE CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 3 RIVER MODIFICATIONS 4 HABITATS AND LAND USE 6 FLOODPLAINS 8 SPECIES OF CONCERN 10 Mission: Promote the protection, restoration, enhancement, understanding, awareness and wise use NATIVE FISHES 13 of the natural resources of the Lower Mississippi River, through coordinated and cooperative efforts involving CLIMATE ADAPTATION 14 research, planning, management, information sharing, public education and advocacy. PLANNING 16 ACCOMPLISHMENTS 18 GOALS AND ACTIONS 22 CITATIONS 24 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 27 Suggested citation: Lower Mississippi River Conservation Committee. 2015. Restoring America’s Greatest River: A Habitat Restoration Plan for the Lower Mississippi River. Published electronically at http://lmrcc.org. Vicksburg, Mississippi. The cover photo, taken by Bruce Reid near Fitler, Mississippi, shows the Mississippi River main channel, a sandbar, a notched dike and the batture forest. © 2015 Lower Mississippi River Conservation Committee 2 INTRODUCTION he Lower Mississippi River Conservation Committee (LMRCC) was founded in 1994 and is a coalition of 12 state natural resource MISSISSIPPI RIVER WATERSHED Tconservation and environmental quality agencies from Arkansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri and Tennessee. The LMRCC Executive Committee has one member from each of the agencies. There are also five federal partners: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE), Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS), U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) and U.S. Geological Survey (USGS). The USFWS provides a coordination office. LMRCC staff work out of the USFWS’s Lower Mississippi River Fish and Wildlife Conservation Office in Jackson, Mississippi. -

Lower Mississippi River Fisheries Coordination Office

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Lower Mississippi River Fisheries Coordination Office Station Facts Activity Highlights ■ Established: 1994. ■ Development of an Aquatic Resource Management Plan to ■ Number of staff: one. restore natural resources in the 2.7 ■ Geographic area covered: million-acre, leveed floodplain of Arkansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, the Lower Mississippi River. Mississippi, Missouri, and ■ Publication of the LMRCC Tennessee. Newsletter, a regional newsletter Station Goals on aquatic resource conservation photo: USFWS photo: ■ Provide a permanent forum for management issues, and natural facilitating the management of the resource-based economic aquatic natural resources of the development. Lower Mississippi River leveed ■ Provide long-term economic, floodplain. environmental, and public ■ Restore and enhance aquatic recreation benefits to the region by habitat in the Lower Mississippi cooperatively addressing aquatic River leveed floodplain and resource management issues. tributaries. Questions and Answers: photo: USFWS photo: ■ Increase public awareness and What does your office do? encourage sustainable use of the The Lower Mississippi River Lower Mississippi River’s natural Fisheries Coordination Office resources. (FCO) coordinates the work of many different state and Federal ■ Promote natural resource-based natural resource management and economic development. environmental quality agencies that deal with the Lower Mississippi River ■ Increase technical knowledge of the aquatic resource issues. Lower Mississippi River’s natural resources. Why is the Lower Mississippi River photo: USFWS photo: important? Services provided to: The Mississippi River is the fourth ■ Project leader serves as longest river in the world, flowing coordinator for the Lower for more than 2,350 miles from its Mississippi River Conservation headwaters in Lake Itasca, Minnesota Committee (LMRCC); LMRCC to the Gulf of Mexico. -

The Upper Mississippi and Illinois Rivers: Value and Importance of These Transport Arteries for U.S

The Upper Mississippi and Illinois Rivers: Value and Importance of these Transport Arteries for U.S. Agriculture FAPRI-UMC Briefing Paper #03-04 June 2004 Prepared by the Food and Agricultural Policy Research Institute 101 South Fifth St. Columbia, MO 65201 573-882-3576 www.fapri.missouri.edu BRIEFING PAPER ON THE UPPER MISSISSIPPI AND ILLINOIS RIVERS: VALUE AND IMPORTANCE OF THESE TRANSPORT ARTERIES FOR U.S. AGRICULTURE Introduction The upper Mississippi River is a 663-mile segment extending from Minneapolis, Minnesota to near St. Louis, Missouri: this waterway forms borders for Minnesota, Iowa, Illinois, Missouri and Wisconsin. The 349-mile Illinois waterway extends from Chicago, Illinois to the confluence of the Illinois and upper Mississippi Rivers near St. Louis, Missouri. Both transport arteries originate important quantities of corn, soybeans and wheat that are transported via the middle and lower Mississippi River to export elevators in the lower Mississippi River port area (3). Past studies indicated over 90 percent of the export-destined corn and soybeans originating in states that border the upper Mississippi and Illinois waterways is destined for lower Mississippi River ports (1, 4). In addition, it is estimated that over half of the U.S.’s corn exports and over a third of the soybean exports originate in states bordering the upper Mississippi and Illinois Rivers and move via these transport arteries to lower Mississippi River ports (1, 4). Clearly, the upper Mississippi and Illinois Rivers are important transport arteries for north central U.S. agriculture, however, as shown by U.S. Army Corps of Engineers data, grain/oilseed movements on these Rivers is also important to the barge industry (5). -

Nutrient Delivery from the Mississippi River to the Gulf of Mexico And

the entire landscape must be considered if hydrologic and water quality models are doi:10.2489/jswc.69.1.26 used to predict the delivery of sediment and nutrients. Similarly, the contribution of other sources (including noncultivated lands, urban areas, forests, and the direct discharge Nutrient delivery from the Mississippi of waste water to streams and rivers) should be accounted for. In addition, processes River to the Gulf of Mexico and effects of occurring in streams, lakes, and reservoirs affect the fate of pollutants as they are trans- cropland conservation ported through the system and should also be included. M.J. White, C. Santhi, N. Kannan, J.G. Arnold, D. Harmel, L. Norfleet, P. Allen, M. DiLuzio, X. Comprehensive water quality simulation Wang, J. Atwood, E. Haney, and M. Vaughn Johnson at the scale of the Mississippi River Basin (MRB, 3,220,000 km2 [1,240,000 mi2]) is Abstract: Excessive nutrients transported from the Mississippi River Basin (MRB) have cre- a difficult task; thus, only a few modeling ated a hypoxic zone within the Gulf of Mexico, with numerous negative ecological effects. efforts at that scale have been conducted Copyright © 2014 Soil and Water Conservation Society. All rights reserved. Furthermore, federal expenditures on agricultural conservation practices have received to date. The contiguous United States was Journal of Soil and Water Conservation intense scrutiny in recent years. Partly driven by these factors, the USDA Conservation simulated by Srinivasan et al. (1998) in the Effects Assessment Project (CEAP) recently completed a comprehensive evaluation of nutri- Hydrologic Unit Model for the United ent sources and delivery to the Gulf.