THE UNIVERSITY of HULL What Kind of Space Does Sheffield

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reaching out to Students

Donor News 10 A fundraising update for University donors and friends Literary hero inspires new Reaching out scholarships. See page 10 for to students the full story. Also inside this issue: Fantastic response to Supporting essential New Exhibition Gallery Bob Boucher appeal – MND research – on show – page 2 page 6 page 12 Fantastic response to Bob Boucher appeal We are delighted to report that – thanks to hundreds of generous donations from alumni, staff, and friends – more than £85,000 has been raised to date for the Bob Boucher Scholarships Fund, in memory of our former Vice-Chancellor. Rosemary Boucher, Bob’s widow, commented, “Through the pages of this magazine I would like to thank all those who have contributed to this scholarship fund in memory of Bob. It means a great deal to my children and me that he was remembered by so many people. We hope that the scholarships will help the next generation of Sheffield students to get the most out of a university which Bob loved.” Professor Bob Boucher’s association with Sheffield spanned nearly 40 years. During his time as Vice- Chancellor, he was instrumental in some of the University’s biggest successes. He spearheaded a range of innovative schemes designed to boost the regional economy, such as the Sheffield Bioincubator, the Advanced Manufacturing Research Centre with Professor Bob Boucher CBE, FREng. Boeing and the Rolls-Royce Factory of the Future. And the University’s estate was transformed under his leadership, including the stunning £23 million library and IT centre, the Information Commons, and the £160 million student residences at Endcliffe and Ranmoor. -

Your University Magazine

Your University. The magazine for alumni and friends of the University of Sheffield • 2007/2008 Rising to the challenge In the spotlight Renaissance Sheffield A meeting of minds A dramatic return Eddie Izzard finally collects his degree We have now received our 3,400th gift from a supporter. Claire Rundström, Development Manager, Alumni Relations, and Miles Stevenson, Director of Development. Miles is in charge of the Development and Alumni Relations Office and the activities it undertakes; Claire manages the full alumni relations programme of communications and events. ‘ Contents Welcome University news 2 to the 2007 issue of Your University magazine. Reflections of the Vice-Chancellor 8 This fifth issue of Your University also marks the fifth anniversary of the Rising to the challenge’ 10 establishment of the Development and Alumni Relations Office. In 2002 only six alumni were making regular donations in support of the University. We have now Sheffield takes Venice received our 3,400th gift from a supporter, bringing the total to more than by storm 12 £500,000. This generosity has funded 100 scholarships, supported the Information Scientist on a mission 13 Commons building and funded the work of the Alumni Foundation. In addition, more than £500,000 has been received through generous legacies. I am constantly Five years on 14 delighted by the interest and enthusiasm our alumni have for the University and A dramatic return 16 its future. Renaissance Sheffield 18 I wish to take this opportunity to thank our Vice-Chancellor, Professor Bob Boucher, for the constant support he has given alumni relations at the University. -

Ut 10,000 People Are Diagnosed Each Year, at Present There Is No Cure for PD

Your University. The magazine for alumni and friends of the University of Sheffield • 2009/2010 Rag renaissance applying creativity to fundraising Understanding our ageing world research unravels the facts A creative heart for WN a Henderson’s Relish gift box. the campus See page 11. explore the Jessop development Our alumni have an important role to play within our community Vice-Chancellor Professor Keith Burnett CBE, FRS Comment I have now had opportunities to meet many of our alumni – work place, with many students taking up opportunities to some in positions of high responsibility on the international gain real-life work experience related to their degrees. Our stage, others working in challenging jobs that have a direct Careers Service is also extending its commitment to provide impact on many lives. One question that recurs in our timely information and advice beyond graduation to new conversations is what the current economic situation means alumni who still require support in the crucial first for the University and its students. I would therefore like to months of finding a career. You can read more at share my views on how we can work together to protect the www.sheffield.ac.uk/careers/students/recession. world-leading quality education and first-class experience for all our students here in Sheffield. But the advice is not just theoretical. Older and more experienced alumni already established in their careers Wherever University graduates and students live in the world, are taking part in mentorship schemes and occupational very few of you can be immune from the economic challenges talks, translating the concept of an alumni network into currently being experienced. -

Your-University08.Pdf

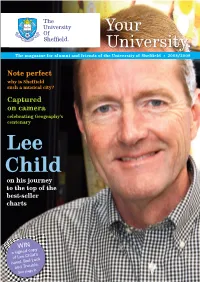

Your University. The magazine for alumni and friends of the University of Sheffield • 2008/2009 Note perfect why is Sheffield such a musical city? Captured on camera celebrating Geography’s centenary Lee Child on his journey to the top of the best-seller charts WIN a signed copy of Lee Child’s novel, Bad Luck and Trouble. See page 9. Alumni merchandise Special commemorative print by Joe Scarborough – Our University As its contribution to the University Centenary, the Sheffield University University tie Association commissioned renowned local artist Joe Scarborough to paint a new work. Our University, evocative of the University past and In 100% silk with multiple present, is now on public display in the entrance to University House. University shields. £18.00 each (incl VAT) plus p+p (£1.00 UK; Unsigned prints measuring 19" x 17” are available to purchase. Unframed and packed in protective cardboard tubes, they are priced at £15.00 £1.30 Europe; £1.70 rest of world). each (incl VAT) plus p+p (£2 UK; £2.50 Europe; £3 rest of world). To place your order for the above merchandise, either download the relevant order form(s) from www.sheffield.ac.uk/alumni/merchandise or contact us on +44 (0) 114 222 1079. Please send completed order forms and your payment to: Development and Alumni Relations Office (Merchandise) The University of Sheffield, 277 Glossop Road, Sheffield S10 2HB UK Payment by cheque or £ sterling draft made payable to ‘The University of Sheffield’. Miles Stevenson, Director of Development, with (left) Claire Rundström, Development Manager, Alumni Relations, and Helen Booth, Alumni Relations Assistant. -

Annual Report 2004/05. J11737 Cover Spreads 15/3/06 9:23 Am Page 3

J11737_Cover Spreads 15/3/06 9:23 am Page 2 Annual Report 2004/05. J11737_Cover Spreads 15/3/06 9:23 am Page 3 Contents Chairman's Foreword 1 Vice-Chancellor’s Introduction 2 Financial Review 4 Investing in the Estate 6 The Dividend of Research 8 Teaching and Learning210 Preparing for Employment 13 Enterprise and Innovation 14 In Partnership with Industry and Commerce 17 Centenary Celebrations 18 Development and Alumni Relations 22 The International Dimension 24 Part of the Region 26 The Union of Students 28 Honours and Distinctions 30 Honorary Degrees 32 Staffing Matters 34 Student Numbers 36 Examination Performance 37 Officers and The Council 38 Facts and Figures 40 The University at a Glance 41 Front Cover: View of Sheffield from Crookes (1923), by the Sheffield-born artist Stanley Royle, showing the University’s red-brick buildings in the centre ground of the picture. The other red-brick buildings to their right housed the mail order business of J.G. Graves, a generous benefactor to the University. (Bridgeman Art Library) Edited by Roger Allum, Public Relations Office. Photography by Ian Spooner. Designed and Printed by Northend Creative Print Solutions, Sheffield. J11737_Uni Annual Report 2005 15/3/06 9:24 am Page 1 ANNUAL REPORT 2004/05 CHAIRMAN’S FOREWORD 1 Chairman’s Foreword The distinctive flavour of the University committees. Mr Paul Firth, a member of Sheffield as a quality institution of of Council, was appointed a Pro- higher education has shone through the Chancellor and I look forward to Centenary celebrations and has served working with him and fellow Council as a reminder of the important role it members as the University enters its is playing at regional, national and second century. -

Annual Report and Accounts 2005/06

Annual Report and Accounts 2005/06 Present to Parliament pursuant to Schedule 1, paragraph 25 (4) of the Health and Social Care (Community Health and Standards) Act 2003 Annual Report and Accounts 2005/06 Welcome 14 Sheffield Teaching We became an NHS Foundation population of approximately Trust on 1st July 2004 as part of 2.2 million people. Some of Hospitals NHS Trust the first wave of hospital trusts our clinical services are came into existence to achieve this new status. The national or international centres 2 5 in 2001 when the Trust now has greater freedom of excellence. from central government, two pre-existing enabling us to set local health Sheffield Teaching Hospitals adult acute trusts in targets and invest more in employs more than 13,000 patient care whilst still staff. Each year, more than Sheffield merged. upholding the ethos of the NHS 175,000 operations and day by providing healthcare free at case procedures are performed the point of delivery. and over 797,000 outpatient appointments are provided The Trust manages the five across the hospitals. adult NHS hospitals in Sheffield; the Northern General, Royal The Trust also has a strong 3 Hallamshire, Charles Clifford, commitment to teaching and Weston Park and Jessop Wing research and is closely linked hospitals, which are situated on with the Universities of two campuses, one centrally Sheffield and Sheffield Hallam. 1 Northern General Hospital located and the other in the north of the city. The Trust 2 Royal Hallamshire Hospital provides general hospital 3 Weston Park -

ANNUAL REPORT 2003/04 Contents

The University of Sheffield ANNUAL REPORT 2003/04 Contents Chairman's Foreword 1 Vice-Chancellor’s Introduction 2 Financial Summary 4 Investing in the Estate 6 The Dividend of Research 8 Teaching and Learning212 Widening Participation 14 Enterprise and Innovation 16 Preparing for Employment 18 In Partnership with Industry and Commerce 20 Part of the Region 22 The Union of Students 24 Honours and Distinctions 26 Honorary and Ex-Officio Degrees 28 Staffing Matters 30 Student Numbers 32 Examination Performance 33 Officers and The Council 35 Facts and Figures 36 The University at a Glance 37 Front Cover: The research work of Professor Tim Birkhead and Professor Tony Cullis is brought together in a montage showing the flight feather of a zebra finch (top) and columns of atoms in indium antimonide. Professors Birkhead and Cullis were elected Fellows of the Royal Society in 2004 (page 10). Edited by Roger Allum, Public Relations Office. Photography by Ian Spooner, Mark Rodgers. Designed and Printed by Northend Creative Print Solutions, Sheffield. ANNUAL REPORT 2003/04 CHAIRMAN’S FOREWORD 1 Chairman’s Foreword This Annual Report highlights the reinforces our commitment to support achievements of the University in a year fully the health care needs of our that Royal Assent was given to the students, while the opening of the Higher Education Bill. In today’s Advanced Manufacturing Research political climate the Bill was seen as the Centre, in partnership with the Boeing universities’ only opportunity of securing Corporation, is an important additional funding. Its passage through contribution to evolving manufacturing Parliament owed much to those who technology and a stimulus to regional championed its cause in the public economic development. -

The Pleasures of Being a Student at the University of Sheffield

The pleasures of being a student at the University of Sheffield M J Cheeseman A thesis submitted in November 2010 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. National Centre for English Cultural Tradition Quality of life is sure to decrease significantly: accept this fact and prepare. You will not be able to justify buying gratuitous fancy dress costumes for those [oh so indispensable, those legendary, those so difficult to get out of] novelty bar crawls: you may have to lower your expectations as to those compliments your costume will invite in flaming, acrid bars - where pub crawls venture too far from their source and motivation - and you will no longer be able to resemble your favourite characters from childhood shows, (those ones you had forgotten until arriving in Freshers' Week and discovering the resurrected interests, the mass hysteria to bond groups with nothing in common but their accident of age); from bemused charity shops, or cynical, colourful, fancy dress shops (that multiply like bacteria populations throughout student areas), as you only abandoned them before ten o'clock on the floor of a pub covered with body paint and sick. -Toby Hobbs I said, Hey stu-dent! Hey stu-dent! Hey stu-dent! You're gonna get it through the head, I said. -The Fall Well the modern world is not so bad Not like the students say In fact I'd be in heaven If you'd share the modern world with me With me in love with the USA now With me in love with the modern world now Put down the cigarette And share the modern world with me. -

Your University Magazine 2003/2004

Master/Sheff_Alumni_Aug03_V2 22/9/03 11:26 am Page BC1 A legacy to Sheffield your2003/2004 A generous bequest to the University from Dr Marjorie Shaw is enabling our undergraduates to study abroad. University Dr Shaw, a lecturer in French strong impression of her presence, Language for over 30 years, died energy, love of the French in 2000 and left a gift of £150,000 language and enthusiasm for to her old department. “Her life teaching it.” was devoted to undergraduate By leaving a gift to the University, students,” said colleague and friend Dr Marjorie Shaw has ensured that Professor David Williams. Her gift her positive influence will continue. was made without conditions, enabling the Department of French The Development and Alumni to decide the most effective way to Relations Office is here to provide advice for alumni who wish to The first Dr Marjorie Shaw Bursary use the legacy. holders: (left-right) Dale Meath, make a gift or leave a legacy in Rick Webb, Danielle Fortier and Dr Marjorie Shaw The gift has been translated into their Will to the University. Jennifer Hutchinson bursaries to help students who find Photo: Miriam Garner themselves in need of financial With your support. Each Dr Marjorie Shaw help we can Bursary, worth £1,000, will support a student during their study year continue to abroad, a crucial part of the French promote undergraduate degree. excellence, Dr Shaw’s long and successful diversity and career at the University, including her close association with Tapton opportunity. and Halifax Halls of Residence, has given many hundreds of alumni Pleasurelands good cause to remember her with gratitude. -

Catch up with Friends from Sheffield

Catch up with friends from Sheffield Sheffield Reunited – the online directory of www.sheffield.ac.uk/sheffield-reunited and use Sheffield alumni – is fast becoming a hive of activity, your unique alumni number (find this on the with over 4,300 people now registered users. questionnaire accompanying this magazine The more people that join, the better it gets! or request it via the Sheffield Reunited website) to register. You can post your own message for visiting alumni to read, update your contact details quickly and easily, And don’t forget to activate and even contact lost friends via the secure email your email forwarding forwarding service. Sheffield Reunited is easy to use, account so that with full instructions provided on the website. lost University friends can be But remember, you have to be registered to take reunited with you. part in Sheffield Reunited, so please visit: www.sheffield.ac.uk/sheffield-reunited www.sheffield.ac.uk/alumni Welcome Contents Welcome to the 2006 issue of Your University magazine. Simply the bes t 2 Home from home 4 2005 was certainly a year to remember as the University celebrated its Charter Centenary. A year-long programme of events celebrated 100 years of excellence and thousands of alumni, The host with the most 5 staff and friends attended prestigious lectures, came back for reunions or took part in special events and dinners in the UK, the Caribbean, the United States and Asia. Many had not been Your news 1 6 back to Sheffield since graduating and the Centenary Year gave them the opportunity to reconnect not only with old friends but also with the University.