The Imagery of Emily Dickinson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

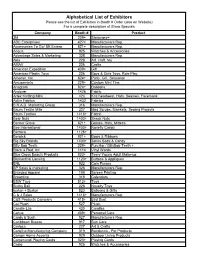

Alphabetical List of Exhibitors

Alphabetical List of Exhibitors Please see the list of Exhibitors in Booth # Order (also on Website) For a complete description of Show Specials Company Booth # Product 3M 209+ Stationery+ ABC Enterprises 427+ Manufacturers Rep. Accessories To Go/ BB Enterp. 821+ Manufacturers Rep. Acqua 925 Watches & Accessories Advantage Sales & Marketing 328 Manufacturers Rep. Alex 228 Art, craft, toy AMAV 226 Crafts American Expedition 409+ Gift American Plastic Toys 226 Boys & Girls Toys, Role Play Amscan, Inc. 824+ Party, Gift, Seasonal Amusemints 229+ Custom Mint Tins Anagram 824+ Balloons Andover 1426 Fabric Artex Knitting Mills 424 Knit headwear, Hats, Beanies, Facemask Avlyn Fabrics 1432 Fabrics B.R.A.D. Marketing Group 316 Manufacturers Rep. Baum Textile Mills 327 Med Scrubs, Blankets, Sewing Projects Baum Textiles 1416+ Fabric Bear Nuts 1400+ Snack Nuts Becker Glove 821+ Gloves, Hats, Mittens Bee International 1400+ Novelty Candy Berroco 1126+ Berwick 921+ Bows & Ribbons Big Sky Brands 1400+ Jones Soda & Candy Billy Bob Teeth 229+ Fun Har / BillyBob Teeth + Black & Red, Inc 1114 Vinyl Words Blue Cross Beauty Products 823+ Teen/ Young Adult Make-up Blumenthal Lansing 1120+ Buttons & Appliques BNL 922 Coin Purses BP Sales & marketing 326 Manufacturers Rep. Branded Apparel 108 Screen Printing Brownline 318 Calendars BSW Toys 512+ Toys Bucky Ball 228 Novelty Toys burton + Burton 523 Balloons & Gifts C & J Sales 1416+ Manufacturers Rep. C&S Products Company 415+ Bird Suet Cal Plush 527 Plush Candle-Lite 420 Candles Canus 409+ Personal Care Cards & Such 527 Manufacturers Rep. Caribbean Breeze 917 Sun Care Carloca 227 Art & Crafts Carolina Manufacturing Company 319 Bandanna - Pet Products Carson Home Accents 929 Outdoor Living Products Cartamundi Playing Cards 323+ Playing Cards Casio 925 Watches & Accessories Alphabetical List of Exhibitors Please see the list of Exhibitors in Booth # Order (also on Website) For a complete description of Show Specials Company Booth # Product Ceaco 226 Puzzles, Games Chapman Bingham Associates 227 Manufacturers Rep. -

Textiles and Clothing the Macmillan Company

Historic, Archive Document Do not assume content reflects current scientific knowledge, policies, or practices. LIBRARY OF THE UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE C/^ss --SOA Book M l X TEXTILES AND CLOTHING THE MACMILLAN COMPANY NEW YORK • BOSTON • CHICAGO • DALLAS ATLANTA • SAN FRANCISCO MACMILLAN & CO., Limited LONDON • BOMBAY • CALCUTTA MELBOURNE THE MACMILLAN CO. OF CANADA, Ltd. TORONTO TEXTILES AXD CLOTHIXG BY ELLEX BEERS >McGO WAX. B.S. IXSTEUCTOR IX HOUSEHOLD ARTS TEACHERS COLLEGE. COLUMBIA U>aVERSITY AXD CHARLOTTE A. WAITE. M.A. HEAD OF DEPARTMENT OF DOMESTIC ART JULIA RICHMAX HIGH SCHOOL, KEW YORK CITY THE MACMILLAX COMPAXY 1919 All righU, reserved Copyright, 1919, By the MACMILLAN company. Set up and electrotyped. Published February, 1919. J. S. Gushing Co. — Berwick & Smith Co. Norwood, Mass., U.S.A. ; 155688 PREFACE This book has been written primarily to meet a need arising from the introduction of the study of textiles into the curriculum of the high school. The aim has been, there- fore, to present the subject matter in a form sufficiently simple and interesting to be grasped readily by the high school student, without sacrificing essential facts. It has not seemed desirable to explain in detail the mechanism of the various machines used in modern textile industries, but rather to show the student that the fundamental principles of textile manufacture found in the simple machines of primitive times are unchanged in the highl}^ developed and complicated machinerj^ of to-day. Minor emphasis has been given to certain necessarily technical paragraphs by printing these in type of a smaller size than that used for the body of the text. -

Ilkplush the Kind Mother Used to Tnavc." Soldier Boys in Uniform Munched the Pungent Gingerbread That Was Made by Mrs

"i" I'wSpWfl''' "'" " 'r,"W1P-r- ' i '. id(' I 'ifiiv'ty '"'r'"r37twyq)il', gar''yyBiBB,it' V 'i . -- EYEtfESt? iPUBrrC EEDGrER-rmrXDELr- HrA', FRIDftYrTjECEMBER 12, 19CJ' lo : r Jnni rTrii - mtmmrtf ,t MANS DELIGHT s H GINGERBREAD y -- Mrs. M. A. Wilson, Evening Pub- - wJK r i it ;. .. teat TYfrOtrisimas .irannrMTC lie Lodger Food Lxport, sur- tie prises Soldiers at Bazaar EGGLESS RECIPES ARE USED "Gee! 'Some gingerbread. That's ilkPlush the kind mother used to tnaVc." Soldier boys In uniform munched the pungent gingerbread that was made by Mrs. Mary A. Wilson, food expert for the Evening Public IiEDor.n, at the vm 100th Infantry bazaar In the First Eleventh and Market.StreetA. trmmLimm m Jrm m Eleventh and Market, Streets. Regiment Armory last night and de- JrJrmmtM Jm M3m. Jr cided It was "some gingerbread." The supply that was made Jot demonstration -- purposes only was exhausted in less timo'' than it takes to tell it, and the ova clamored for more. Famous the World Over as the Plushes That Look Like Fur That Preserve In her talk on economical recipes and the elimination of waste in cooking, Jin. Wilson startled the housewives by tell- ing them that it it were not for the the Silken Textures Genuine Wear Better Than of Furs and cheaper cuts of Fur lorcigners who ue the taeat steaks would cost from SZ.nO to $3 a pound. "The yoifng housewife of today never thinks of buying a piece of neck or ENTIRE floor devoted exclusively to these coats, fashioned of the WORLD-RENOWNE- D EVENT only possible at FRANK ik SEDER'S, because, recognizing the shin, or any other cheaper cuts of meat unless tbev are drcBscd up by the butcher AN "SALT'S" SILK PLUSHES AND FUR FABRICS. -

Back Cushions & Throw Pillows Down Plush

BACK CUSHIONS & THROW PILLOWS IN THE INTEREST OF ENVIRONMENTAL STEWARDSHIP, OUR STANDARD CUSHION IS naturalLEE. AS OF MARCH 3, 2014, LEE INDUSTRIES IS 100% COMPLIANT TO THE TB117-2013 FLAMMABILITY REQUIREMENTS. THIS LEGISLATION ALLOWS LEE TO SHIP OUR FR FREE (FLAME RETARDANT FREE) CUSHIONS, FOAM, FABRIC & DECKING PRODUCTS THROUGHOUT THE COUNTRY. DOWNPROOF TICKING – 50% COTTON/50% POLYESTER FR FREE (FLAME RETARDANT FREE) FEATHER/DOWN – 90% FEATHERS/10% DOWN AND HYPOALLERGENIC BACK CUSHION & THROW PILLOW OPTIONS naturalLEE DOWNPROOF TICKING RECYCLED & REGENERATED FIBER *EXTRA FIRM naturalLEE AVAILABLE PLUSH DOWNPROOF MICRO DENIER TICKING FIBER (AN ALLERGY-FREE DOWN REPLACEMENT) DOWN DOWNPROOF TICKING 90% FEATHER/ 10% DUCK DOWN CUSHION PACKAGE DESCRIPTIONS NATURALLEE CUSHION PACKAGE NATURALLEE SEATS, BACKS AND THROW PILLOWS SPRING FIBER CUSHION PACKAGE SPRING FIBER SEATS WITH PLUSH BACKS AND THROW PILLOWS CLOUD NINE CUSHION PACKAGE CLOUD NINE SEATS WITH DOWN BACKS AND THROW PILLOWS PLUSH NINE CUSHION PACKAGE CLOUD NINE SEATS WITH PLUSH BACKS AND DOWN THROW PILLOWS HAVEN CUSHION PACKAGE HAVEN SEATS WITH DOWN BACKS AND THROW PILLOWS . -

Fabric Supplier List

FABRIC SUPPLIER LIST CANADA Kendor Textiles Ltd 1260 Cliveden Ave Delta BC V3M 6Y1 Canada 604.434.3233 [email protected] www.kendortextiles.com Fabrics Available: Fabric supplier. Eco-friendly. Organic. Knits: solids, prints, yarn dyes and warp. Wovens: solids and yarn dyes. End Use: activewear, bottomweights, medical, lingerie, childrenswear, swimwear, rainwear, skiwear and uniform. Natural & eco items include cottons, bamboo's, modals, linens, hemps, organic cottons & organic linens. Technical items include waterproof/breathable soft shells, antibacteric & wicking polyester & recycled polyesters. Is a proud representative of the British Millerain line of waxed cottons and wools, and are able to provide custom souring. Minimums: Carries stock. In-stock minimum: 5 yards/color. Minimum order for production: 10 yards/color. Gordon Fabrics LTD #1135-6900 Graybar Rd. Richmond BC Canada 604.275.2672 [email protected] Fabrics Available: Fabric Supplier. Importer. Jobber. Carries stock. Knits & Wovens: solids, prints, yarn dyes and novelties. End Use: activewear, borromweights, eveningwear/bridal, medical, lingerie and childrenswear. Minimums: In stock minimum 1 yard. Minimum order for production varies. StartUp Fashion Supplier List 2016 – Page 1 CHINA Ecopel (HX) Co., Ltd. China +86 216.767.9686 www.ecopel.cn Fabrics Available: Fake fur and leather garments. End Uses: Childrenswear, Menswear, Other, Womenswear. Minimums: Min. order 50-100 m Hangzhou New Design Source Textile Co., Ltd. China +86 057.182.530528 Fabrics Available: Knits, Polyester/Man-Made, Prints. End Uses: Juniors Fashion, Menswear, Womenswear. Minimums: Min order 50 m. Nantong Haukai Textile Co., Ltd. China +86 513.890.78626 www.huakaitex.com Fabrics Available: Cotton, Linen. End Uses: Corporatewear/Suiting, Menswear, Womenswear. -

Rosenbaum Co

B atd Back o s , Boquet Tables , C P hoto ra hs abinet g p , C C hristmas ards , t ain P l Cun o es , Dis l a ; F p ) rames , Gra hosco es p p , Hat . and Clothes Racks M ouldi n s an d g Linings , P I DE H b I s 1 1 H LA LP IA O cto er t 8 8 . DE AR S I R I n es e s se e e pr nting thi , our cond catalogu , to your notic , w e b eg to i nform you that w e have spared no e ffort to have s k s se s s ss all e s e s our toc thi a on urpa our pr viou ffort . T he detail and varie ty a re s o extens ive that you cannot s s e ex n as t he es afford to pa it without car ful ami ation , pric s e e s e es mu t comm nd th m lv to you . T he workmanship and quality w e guarantee fi rst - class i n e e es e s the s b e e e v ry r p ct, mo t of good ing mad und r our s s v s onal uper i ion . es e e s e e s s Corr pond nc an w r d promptly and ati factorily . " “ W e s e e k e s e want your ampl ord r, nowing that , onc tart d , s e e can ll you r gularly . -

Geiger Textiles Price List

Price List and Specification Guide EFFECTIVE JUNE 2021 02 Textiles 84 Price Groups 85 Custom Finishes 86 Warranty 87 Additional Information 88 Maintenance Guidelines 800.456.6452 geigertextiles.com © 2021 Geiger 1 Allusion DESIGNED BY BASSAMFELLOWS APPLICATION Seating CONTENT 60% Alpaca, 27% Wool, 13% Nylon BACKING Cotton WIDTH 56" REPEAT None ABRASION 95,000 Cycles, Martindale* FLAMMABILITY CA TB 117-2013 WEIGHT 25.2 Oz Per Linear Yard 1GS01 Moonlight 1GS02 Pearl Gray 1GS03 Platinum ORIGIN Italy ENVIRONMENTAL SCS Indoor Advantage™ Gold Contains Bio-Based Materials FR Chemical Free Prop 65 Chemical Free REACH Compliant Healthier Hospitals Compliant Living Future Red List Compliant WELL Building Standard Compliant 1GS04 Smoky Taupe 1GS05 Camel 1GS06 Swiss Red MAINTENANCE S – Clean with Mild, Dry Cleaning Solvent CUSTOM FINISHES Alta™ Plush PRICE GROUP 8 NET PRICE $135 Per Yard *Abrasion test results exceeding ACT Performance Guidelines are not an indicator of product lifespan. Multiple factors affect fabric durability 1GS07 Chestnut 1GS08 Deep 1GS09 Navy Brown Cerulean and appearance retention. 1GS10 Black Green 1GS11 Sterling 1GS12 Anthracite 800.456.6452 geigertextiles.com © 2021 Geiger 2 Alpaca Mohair DESIGNED BY SUSAN LYONS APPLICATION Seating CONTENT 100% Alpaca BACKING Cotton/Polyester WIDTH 54" REPEAT None ABRASION 40,000 Cycles, Martindale FLAMMABILITY CA TB 117-2013 WEIGHT 29.7 Oz Per Linear Yard 18510 Dune 18511 Trench 18512 Vicuna ORIGIN Belgium ENVIRONMENTAL SCS Indoor Advantage™ Gold Contains Bio-Based Materials FR Chemical -

Maine Women and Fashion, 1790-1840

Maine History Volume 31 Number 1 My Best Wearing Apparel Maine Article 3 Women and Fashion, 1800-1840 3-1-1991 "So Monstrous Smart" : Maine Women and Fashion, 1790-1840 Kerry A. O'Brien York Institute Museum Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mainehistoryjournal Part of the Cultural History Commons, Fashion Design Commons, Fiber, Textile, and Weaving Arts Commons, United States History Commons, and the Women's History Commons Recommended Citation O'Brien, Kerry A.. ""So Monstrous Smart" : Maine Women and Fashion, 1790-1840." Maine History 31, 1 (1991): 12-43. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mainehistoryjournal/vol31/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maine History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Figure 3. N umber 4. 12 “So M onstrous S mart” (& ?£ ?£ ?$- ?£ ?& ?£ ^ ^ ^ “So Monstrous Smart”: Maine Women and Fashion, 1790 -1840 Kerry A. O'Brien When she died in 1836, Abigail Emerson of York, Maine, left her daughter, Clarissa, an intimate legacy: her clothing. In her will Mrs. Emerson itemized her “Best Wearing Apparel” : shimmies and drawers, caps, calash, stockings, long cotton shirt, Merino Shawl, Black lace veil, Bombazine gown, Silk Pelise, M uff and Tippet Clarissas inheritance included a dress of imported wool and silk twill, a soft wool shawl, a stylish veil, and a variety of caps, probably of thin white muslin. Outerwear also figured in Abigail Emerson s “best ap parel.” A silk coat-dress called a pelisse could have been worn as an outer garment. -

Identifying Woven Textiles 1750-1950 Identification

Identifying Woven Textiles 1750–1950 DATS in partnership with the V&A 1 Identifying Woven Textiles 1750–1950 This information pack has been produced to accompany two one-day workshops taught by Katy Wigley (Director, School of Textiles) and Mary Schoeser (Hon. V&A Senior Research Fellow), held at the V&A Clothworkers’ Centre on 19 April and 17 May 2018. The workshops are produced in collaboration between DATS and the V&A. The purpose of the workshops is to enable participants to improve the documentation and interpretation of collections and make them accessible to the widest audience. Participants will have the chance to study objects at first hand to help increase their confidence in identifying woven textile materials and techniques. This information pack is intended as a means of sharing the knowledge communicated in the workshops with colleagues and the wider public and is also intended as a stand-alone guide for basic weave identification. Other workshops / information packs in the series: Identifying Textile Types and Weaves Identifying Printed Textiles in Dress 1740–1890 Identifying Handmade and Machine Lace Identifying Fibres and Fabrics Identifying Handmade Lace Front Cover: Lamy et Giraud, Brocaded silk cannetille (detail), 1878. This Lyonnais firm won a silver gilt medal at the Paris Exposition Universelle with a silk of this design, probably by Eugene Prelle, their chief designer. Its impact partly derives from the textures within the many-coloured brocaded areas and the markedly twilled cannetille ground. Courtesy Francesca Galloway. 2 Identifying Woven Textiles 1750–1950 Table of Contents Page 1. Introduction 4 2. Tips for Dating 4 3. -

Automotive Towels & Cloths Product Catalog 2015

Automotive Towels & Cloths Product Catalog 2015 Elite Plush Microfiber Detailing Towels Weights: (SKU): Colors (edge): 360 g/m2 (T365) Light Blue 530 g/m2 (T535) Black (red, silver) Gold (black) White (blue, red) Black (red, silver) Lime Green Sizes: Edges: 12”x12” Zero Edge 16”x16” Hemmed Edge 16”x24” Silk Banding 25”x36” Cloth Banding Blend: 75% Polyester, 25% Polyamide 100% Split Microfiber The Elite Plush Detailing Towels are a favorite for auto detailing because of their versatility. They feature a high pile and a low pile side. The high pile side provides extra cushion and fiber depth to minimize scratching, and the low pile side provides effective cutting of wax and polish residue and glass cleaning. Elite Ultra Fine Microfiber Detailing Towels Weights: (SKU): Colors (edge): 400 g/m2 (T407) Blue (black) 500 g/m2 (T507) Gold (gold, black) White (gold, black) Sizes: Edges: 16”x16” Zero Edge 16”x24” Silk Banding Blend: 70% Polyester, 30% Polyamide 100% Split Microfiber The Elite Ultra-Fine Detailing Towels feature the same high and short pile as the Elite Plush Detailing towels, but are made from a finer yarn and are 70% polyester and 30% polyamide. They are preferred towels for top of the line professional detailers. With the correct technique there will be minimal micro scratching. 858-751-2481 [email protected] Microfiber Duo Plush Detailing Towels Colors (edge): Weights: (SKU): Colors (edge): Light Blue 600 g/m2 (T605) Green Black (red, silver) 700 g/m2 (T705) Grey (red) Gold (black) 860 g/m2 (TPK860) Blue White (blue, red) 1100 g/m2 (T1100) Blue/Grey Black (red, silver) White Lime Green Dark Blue (black, silver) Edges: Sizes: Edges: Zero Edge 16”x16” Silk Banding, Hemmed Edge 16”x24” Cloth Banding Silk Banding Overlock Stitch Cloth Banding Blend: 75% Polyester, 25% Polyamide 100% Split Microfiber The Duo Plush Detailing Towels are typically used for quick detailing, waterless car wash, finish work, and towel wash wipe downs. -

2020 Master Price List.Pdf

Master Price List Fabric and Vinyl Suggested Retail March 2020 504 44th Street SE · Kentwood, MI 49548 Phone 800.253.3800 · Fax 616.531.3463 www.luxuryfabrics.com 800.253.3800 Welcome to Luxury Fabrics! Luxury Fabrics is proud to be a family owned and run company. We are dedicated to bringing the highest quality fabric and vinyl to the residential, commercial, and marine upholstery markets. Established in 1966, and enjoying over 53 years of trusted service to our customer base, Luxury Fabrics is one of the most trusted fabric and supply distributors in the United Sates. Offering a full line of upholstery tools and supplies and the in-house capability to custom cut foam seating cushions, we are sure to have your supply needs covered. Give us a call and see what we can do for you! We thank you for choosing Luxury Fabrics and we appreciate the opportunity to serve your product needs. FEATURING NANO PERFORMANCE FABRICS Luxury Fabrics was the first fabric distributor to include NANO performance finish as standard on many of our fabric selections. As this permanent finish has become more popular there are many trade names that are represented. We offer Nanotex, DEFEND, Barricade, NANOSPHERE, and Nanolux just to name a few. These are high performance nanotechnology finishes that build permanent spill and stainRESISTANCE into the fiber structure of the fabric. We understand the need to have superior stain resistance on fabrics for home and office environments. As a “No Charge” upgrade VALUE ADDED feature, we are dedicated to providing the best possible product for your customer. -

Guidance on the Textile Products (Labelling and Fibre Composition) Regulations 2012

TEXTILE LABELLING REGULATIONS Guidance on the Textile Products (Labelling and Fibre Composition) Regulations 2012 JULY 2012 Guidance Notes Regulation (EU) No 1007/2011 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27th September 2011 on textile fibres and related labelling and marking of the fibre composition of textile products and repealing Council Directive 73/44/EEC and Directives 96/73/EC and 2008/121/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council (“the EU Regulation”) and The Textile Products (Labelling and Fibre Composition) Regulations 2011 (SI 2012 No.1102) (“the UK Regulations”) These guidance notes have been produced to provide guidance to business on the EU Regulation and the UK Regulations. However, they do not carry any legal authority and should be read in conjunction with the legislation itself. 2 The Textile Products (Labelling and Fibre Composition) Regulations 2012 Contents Contents .......................................................................................................................................... 3 The EU Regulation .......................................................................................................................... 4 The definition of a textile product ................................................................................................. 4 The expressions ‘100 %’, ‘pure’ and ‘all’ ...................................................................................... 5 Use of the term ‘wool’....................................................................................................................