Armillary Spheres and Scientific Instruments in Renaissance Life and Art

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dunhuang Chinese Sky: a Comprehensive Study of the Oldest Known Star Atlas

25/02/09JAHH/v4 1 THE DUNHUANG CHINESE SKY: A COMPREHENSIVE STUDY OF THE OLDEST KNOWN STAR ATLAS JEAN-MARC BONNET-BIDAUD Commissariat à l’Energie Atomique ,Centre de Saclay, F-91191 Gif-sur-Yvette, France E-mail: [email protected] FRANÇOISE PRADERIE Observatoire de Paris, 61 Avenue de l’Observatoire, F- 75014 Paris, France E-mail: [email protected] and SUSAN WHITFIELD The British Library, 96 Euston Road, London NW1 2DB, UK E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: This paper presents an analysis of the star atlas included in the medieval Chinese manuscript (Or.8210/S.3326), discovered in 1907 by the archaeologist Aurel Stein at the Silk Road town of Dunhuang and now held in the British Library. Although partially studied by a few Chinese scholars, it has never been fully displayed and discussed in the Western world. This set of sky maps (12 hour angle maps in quasi-cylindrical projection and a circumpolar map in azimuthal projection), displaying the full sky visible from the Northern hemisphere, is up to now the oldest complete preserved star atlas from any civilisation. It is also the first known pictorial representation of the quasi-totality of the Chinese constellations. This paper describes the history of the physical object – a roll of thin paper drawn with ink. We analyse the stellar content of each map (1339 stars, 257 asterisms) and the texts associated with the maps. We establish the precision with which the maps are drawn (1.5 to 4° for the brightest stars) and examine the type of projections used. -

Measuring the Universe: a Brief History of Time

Measuring the Universe A Brief History of Time & Distance from Summer Solstice to the Big Bang Michael W. Masters Outline • Seasons and Calendars • Greece Invents Astronomy Part I • Navigation and Timekeeping • Measuring the Solar System Part II • The Expanding Universe Nov 2010 Measuring the Universe 2 Origins of Astronomy • Astronomy is the oldest natural science – Early cultures identified celestial events with spirits • Over time, humans began to correlate events in the sky with phenomena on earth – Phases of the Moon and cycles of the Sun & stars • Stone Age cave paintings show Moon phases! – Related sky events to weather patterns, seasons and tides • Neolithic humans began to grow crops (8000-5500 BC) – Agriculture made timing the seasons vital – Artifacts were built to fix the dates of the Vernal Equinox and the Summer Solstice A 16,500 year old night • Astronomy’s originators sky map has been found include early Chinese, on the walls of the famous Lascaux painted Babylonians, Greeks, caves in central France. Egyptians, Indians, and The map shows three bright stars known today Mesoamericans as the Summer Triangle. Source: http://ephemeris.com/history/prehistoric.html Nov 2010 Measuring the Universe 3 Astronomy in Early History • Sky surveys were developed as long ago as 3000 BC – The Chinese & Babylonians and the Greek astronomer, Meton of Athens (632 BC), discovered that eclipses follow an 18.61-year cycle, now known as the Metonic cycle – First known written star catalog was developed by Gan De in China in 4 th Century BC – Chinese -

The Geography of Ptolemy Elucidated

The Grography of Ptolemy The geography of Ptolemy elucidated Thomas Glazebrook Rylands 1893 • A brief outline of the rise and progress of geographical inquiry prior to the time of Ptolemy. §1.—Introductory. IN tracing the early progress of Geography it is necessary to remember that, like all other sciences, it arose from “ small beginnings.” When men began to move from place to place they naturally desired to tell the tale of their wanderings, both for their own satisfaction and for the information of others. Such accounts have now perished, but their results remain in the earliest records extant ; hence, it is impossible to begin an investigation into the history of Geography at the true fountain-head, though it is in some instances possible to guess the nature of the source from the character of the resultant stream. A further difficulty lies in the question as to where the science of Geography begins. A Greek would probably have answered when some discoverer first invented a method for map- ping out the distance between certain places, which distance conversely could be ascertained directly from the map. In accordance with modern method, the science of Geography might be said to begin when the subject ceased to be dealt with mythically or dogmatically ; when facts were collected and reduced to laws, while these laws again, or their prior facts, were connected with other laws—in the case of Geography with those of Mathematics and Astro- nomy. Perhaps it would be better to follow the latter principle of division, and consequently the history of Geography may be divided into two main stages—“ Pre-Scientific” and Scientific Geography—though strictly speaking, the name of Geography should be applied to the latter alone. -

Thinking Outside the Sphere Views of the Stars from Aristotle to Herschel Thinking Outside the Sphere

Thinking Outside the Sphere Views of the Stars from Aristotle to Herschel Thinking Outside the Sphere A Constellation of Rare Books from the History of Science Collection The exhibition was made possible by generous support from Mr. & Mrs. James B. Hebenstreit and Mrs. Lathrop M. Gates. CATALOG OF THE EXHIBITION Linda Hall Library Linda Hall Library of Science, Engineering and Technology Cynthia J. Rogers, Curator 5109 Cherry Street Kansas City MO 64110 1 Thinking Outside the Sphere is held in copyright by the Linda Hall Library, 2010, and any reproduction of text or images requires permission. The Linda Hall Library is an independently funded library devoted to science, engineering and technology which is used extensively by The exhibition opened at the Linda Hall Library April 22 and closed companies, academic institutions and individuals throughout the world. September 18, 2010. The Library was established by the wills of Herbert and Linda Hall and opened in 1946. It is located on a 14 acre arboretum in Kansas City, Missouri, the site of the former home of Herbert and Linda Hall. Sources of images on preliminary pages: Page 1, cover left: Peter Apian. Cosmographia, 1550. We invite you to visit the Library or our website at www.lindahlll.org. Page 1, right: Camille Flammarion. L'atmosphère météorologie populaire, 1888. Page 3, Table of contents: Leonhard Euler. Theoria motuum planetarum et cometarum, 1744. 2 Table of Contents Introduction Section1 The Ancient Universe Section2 The Enduring Earth-Centered System Section3 The Sun Takes -

Models for Earth and Maps

Earth Models and Maps James R. Clynch, Naval Postgraduate School, 2002 I. Earth Models Maps are just a model of the world, or a small part of it. This is true if the model is a globe of the entire world, a paper chart of a harbor or a digital database of streets in San Francisco. A model of the earth is needed to convert measurements made on the curved earth to maps or databases. Each model has advantages and disadvantages. Each is usually in error at some level of accuracy. Some of these error are due to the nature of the model, not the measurements used to make the model. Three are three common models of the earth, the spherical (or globe) model, the ellipsoidal model, and the real earth model. The spherical model is the form encountered in elementary discussions. It is quite good for some approximations. The world is approximately a sphere. The sphere is the shape that minimizes the potential energy of the gravitational attraction of all the little mass elements for each other. The direction of gravity is toward the center of the earth. This is how we define down. It is the direction that a string takes when a weight is at one end - that is a plumb bob. A spirit level will define the horizontal which is perpendicular to up-down. The ellipsoidal model is a better representation of the earth because the earth rotates. This generates other forces on the mass elements and distorts the shape. The minimum energy form is now an ellipse rotated about the polar axis. -

Anaximander and the Problem of the Earth's Immobility

Binghamton University The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB) The Society for Ancient Greek Philosophy Newsletter 12-28-1953 Anaximander and the Problem of the Earth's Immobility John Robinson Windham College Follow this and additional works at: https://orb.binghamton.edu/sagp Recommended Citation Robinson, John, "Anaximander and the Problem of the Earth's Immobility" (1953). The Society for Ancient Greek Philosophy Newsletter. 263. https://orb.binghamton.edu/sagp/263 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). It has been accepted for inclusion in The Society for Ancient Greek Philosophy Newsletter by an authorized administrator of The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). For more information, please contact [email protected]. JOHN ROBINSON Windham College Anaximander and the Problem of the Earth’s Immobility* N the course of his review of the reasons given by his predecessors for the earth’s immobility, Aristotle states that “some” attribute it I neither to the action of the whirl nor to the air beneath’s hindering its falling : These are the causes with which most thinkers busy themselves. But there are some who say, like Anaximander among the ancients, that it stays where it is because of its “indifference” (όμοιότητα). For what is stationed at the center, and is equably related to the extremes, has no reason to go one way rather than another—either up or down or sideways. And since it is impossible for it to move simultaneously in opposite directions, it necessarily stays where it is.1 The ascription of this curious view to Anaximander appears to have occasioned little uneasiness among modern commentators. -

Our Place in the Universe Sun Kwok

Our Place in the Universe Sun Kwok Our Place in the Universe Understanding Fundamental Astronomy from Ancient Discoveries Second Edition Sun Kwok Faculty of Science The University of Hong Kong Hong Kong, China This book is a second edition of the book “Our Place in the Universe” previously published by the author as a Kindle book under amazon.com. ISBN 978-3-319-54171-6 ISBN 978-3-319-54172-3 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-54172-3 Library of Congress Control Number: 2017937904 © Springer International Publishing AG 2017 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. -

10 · Greek Cartography in the Early Roman World

10 · Greek Cartography in the Early Roman World PREPARED BY THE EDITORS FROM MATERIALS SUPPLIED BY GERMAINE AUJAe The Roman republic offers a good case for continuing to treat the Greek contribution to mapping as a separate CONTINUITY AND CHANGE IN THEORETICAL strand in the history ofclassical cartography. While there CARTOGRAPHY: POLYBIUS, CRATES, was a considerable blending-and interdependence-of AND HIPPARCHUS Greek and Roman concepts and skills, the fundamental distinction between the often theoretical nature of the Greek contribution and the increasingly practical uses The extent to which a new generation of scholars in the for maps devised by the Romans forms a familiar but second century B.C. was familiar with the texts, maps, satisfactory division for their respective cartographic in and globes of the Hellenistic period is a clear pointer to fluences. Certainly the political expansion of Rome, an uninterrupted continuity of cartographic knowledge. whose domination was rapidly extending over the Med Such knowledge, relating to both terrestrial and celestial iterranean, did not lead to an eclipse of Greek influence. mapping, had been transmitted through a succession of It is true that after the death of Ptolemy III Euergetes in well-defined master-pupil relationships, and the pres 221 B.C. a decline in the cultural supremacy of Alex ervation of texts and three-dimensional models had been andria set in. Intellectual life moved to more energetic aided by the growth of libraries. Yet this evidence should centers such as Pergamum, Rhodes, and above all Rome, not be interpreted to suggest that the Greek contribution but this promoted the diffusion and development of to cartography in the early Roman world was merely a Greek knowledge about maps rather than its extinction. -

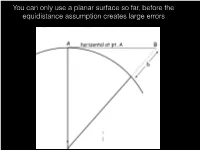

You Can Only Use a Planar Surface So Far, Before the Equidistance Assumption Creates Large Errors

You can only use a planar surface so far, before the equidistance assumption creates large errors Distance error from Kiester to Warroad is greater than two football fields in length So we assume a spherical Earth P. Wormer, wikimedia commons Longitudes are great circles, latitudes are small circles (except the Equator, which is a GC) Spherical Geometry Longitude Spherical Geometry Note: The Greek letter l (lambda) is almost always used to specify longitude while f, a, w and c, and other symbols are used to specify latitude Great and Small Circles Great circles splits the Small circles splits the earth into equal halves earth into unequal halves wikipedia geography.name All lines of equal longitude are great circles Equator is the only line of equal latitude that’s a great circle Surface distance measurements should all be along a great circle Caliper Corporation Note that great circle distances appear curved on projected or flat maps Smithsonian In GIS Fundamentals book, Chapter 2 Latitude - angle to a parallel circle, a small circle parallel to the Equatorial great circle Spherical Geometry Three measures: Latitude, Longitude, and Earth Radius + height above/ below the sphere (hp) How do we measure latitude/longitude? Well, now, GNSS, but originally, astronomic measurements: latitude by north star or solar noon angles, at equinox Longitude Measurement Method 1: The Earth rotates 360 degrees in a day, or 15 degrees per hour. If we know the time difference between 2 points, and the longitude of the first point (Greenwich), we can determine the longitude at our current location. Method 2: Create a table of moon-star distances for each day/time of the year at a reference location (Greenwich observatory) Measure the same moon-star distance somewhere else at a standard or known time. -

User Guide 2.0

NORTH CELESTIAL POLE Polaris SUN NORTH POLE E Q U A T O R C SOUTH POLE E L R E S T I A L E Q U A T O EARTH’S AXIS EARTH’S SOUTH CELESTIAL POLE USER GUIDE 2.0 WITH AN INTRODUCTION 23.45° TO THE MOTIONS OF THE SKY meridian E horizon W rise set Celestial Dynamics Celestial Dynamics CelestialCelestial Dynamics Dynamics CelestialCelestial Dynamics Dynamics 2019 II III Celestial Dynamics Celestial Dynamics FULLSCREEN CONTENTS SYSTEM REQUIREMENTS VI SKY SETTINGS 24 CONSTELLATIONS 24 HELP MENU INTRODUCTION 1 ZODIAC 24 BASIC CONCEPTS 2 CONSTELLATION NAMES 24 CENTRED ON EARTH 2 WORLD CLOCKASTRONOMYASTROLOGY MINIMAL STAR NAMES 25 SEARCH LOCATIONS THE CELESTIAL SPHERE IS LONG EXPOSURE 25 A PROJECTION 2 00:00 INTERSTELLAR GAS & DUST 25 A FIRST TOUR 3 EVENTS & SKY GRADIENT 25 PRESETS NOTIFICATIONS LOOK AROUND, ZOOM IN AND OUT 3 GUIDES 26 SEARCH LOCATIONS ON THE GLOBE 4 HORIZON 26 CENTER YOUR VIEW 4 SKY EARTH SOLAR PLANET NAMES 26 SYSTEM ABOUT & INFO FULLSCREEN 4 CONNECTIONS 26 SEARCH LOCATIONS TYPING 5 CELESTIAL RINGS 27 ADVANCED SETTINGS FAVOURITES 5 EQUATORIAL COORDINATES 27 QUICK START QUICK VIEW OPTIONS 6 FAVOURITE LOCATIONS ORBITS 27 VIEW THE USER INTERFACE 7 EARTH SETTINGS 28 GEOCENTRIC HOW TO EXIT 7 CLOUDS 28 SCREENSHOT PRESETS 8 HI -RES 28 POSITION 28 HELIOCENTRIC WORLD CLOCK 9 COMPASS CELESTIAL SPHERE SEARCH LOCATIONS TYPING 10 THE MOON 29 FAVOURITES 10 EVENTS & NOTIFICATIONS 30 ASTRONOMY MODE 15 SETTINGS 31 VISUAL SETTINGS ASTROLOGY MODE 16 SYSTEM NOTIFICATIONS 31 IN APP NOTIFICATIONS 31 MINIMAL MODE 17 ABOUT 32 THE VIEWS 18 ADVANCED SETTINGS 32 SKY VIEW 18 COMPASS ON / OFF 19 ASTRONOMICAL ALGORITHMS 33 EARTH VIEW 20 SCREENSHOT 34 CELESTIAL SPHERE ON / OFF 20 HELP 35 TIME CONTROL SOLAR SYSTEM VIEW 21 FINAL THOUGHTS 35 GEOCENTRIC / HELIOCENTRIC 21 TROUBLESHOOTING 36 VISUAL SETTINGS 22 CONTACT 37 CLOCK SETTINGS 22 ASTRONOMICAL CONCEPTS 38 ECLIPTIC CLOCK FACE 22 EQUATORIAL CLOCK FACE 23 IV V INTRODUCTION SYSTEM REQUIREMENTS The Cosmic Watch is a virtual planetarium on your mobile device. -

Paths Between Points on Earth: Great Circles, Geodesics, and Useful Projections

Paths Between Points on Earth: Great Circles, Geodesics, and Useful Projections I. Historical and Common Navigation Methods There are an infinite number of paths between two points on the earth. For navigation purposes there are only a few historically common choices. 1. Sailing a latitude. Prior to a good method of finding longitude at sea, you sailed north or south until you cane to the latitude of your destination then you sailed due east or west until you reached your goal. Of course if you choose the wrong direction, you can get in big trouble. (This happened in 1707 to a British fleet that sunk when it hit rocks. This started the major British program for a longitude method useful at sea.) In this method the route follows the legs of a right triangle on the sphere. Just as in right triangles on the plane, the hypotenuse is always shorter than the sum of the other two sides. This method is very inefficient, but it was all that worked for open ocean sailing before 1770. 2. Rhumb Line A rhumb line is a line of constant bearing or azimuth. This is not the shortest distance on a long trip, but it is very easy to follow. You just have to know the correct azimuth to use to get between two sites, such as New York and London. You can get this from a straight line on a Mercator projection. This is the reason the Mercator projection was invented. On other projections straight lines are not rhumb lines. 3. Great Circle On a spherical earth, a great circle is the shortest distance between two locations. -

Armillary Sphere

Armillary Sphere Inventory no. 45453 Armillary sphere Armillary sphere for demonstration of the heavenly spheres made and signed by Carlo Plato, Rome, c.1588. The armillary sphere is an instrument that extends right back to the ancients, and was certainly in used by the second-century astronomer and mathematician Claudius Ptolemy, of Alexandria. It was a mathematical instrument designed to demonstrate the movement of the celestial sphere about a stationary Earth at its centre. The concept of the celestial sphere was fundamental to astronomy from Antiquity through the Middle Ages and into the Early-Modern era. At the centre of the sphere is the Earth. As the Earth is stationary in this model, it is the celestial sphere which rotates about it and acts as a reference system for locating the celestial bodies – stars, in particular – from a geocentric perspective. The instrument survived throughout the medieval period into the early modern era, and in many respects came to symbolise the queen of the sciences, astronomy. It wasn’t until the middle of the sixteenth-century that the basis of the instrument – a geocentric concept of the Universe – was seriously challenged by the Polish mathematician, Nicolaus Copernicus. Even then, the instrument still continued to serve a useful purpose as a purely mathematical instrument. Portrait of Nicolas Copernicus 1580 Held stationary at the centre is a small brass sphere representing the Earth. About it rotate a set of rings representing the heavens – the celestial sphere – one complete revolution approximating to a day or 24 hours. The sphere is mounted at the celestial poles which define the axis of rotation, and its structure includes an equatorial ring and, parallel to this, above and below, two smaller rings representing the Tropic of Cancer to the north, and the Tropic of Capricorn to the south.