Australian Ringneck

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Recommended Band Size List Page 1

Jun 00 Australian Bird and Bat Banding Scheme - Recommended Band Size List Page 1 Australian Bird and Bat Banding Scheme Recommended Band Size List - Birds of Australia and its Territories Number 24 - May 2000 This list contains all extant bird species which have been recorded for Australia and its Territories, including Antarctica, Norfolk Island, Christmas Island and Cocos and Keeling Islands, with their respective RAOU numbers and band sizes as recommended by the Australian Bird and Bat Banding Scheme. The list is in two parts: Part 1 is in taxonomic order, based on information in "The Taxonomy and Species of Birds of Australia and its Territories" (1994) by Leslie Christidis and Walter E. Boles, RAOU Monograph 2, RAOU, Melbourne, for non-passerines; and “The Directory of Australian Birds: Passerines” (1999) by R. Schodde and I.J. Mason, CSIRO Publishing, Collingwood, for passerines. Part 2 is in alphabetic order of common names. The lists include sub-species where these are listed on the Census of Australian Vertebrate Species (CAVS version 8.1, 1994). CHOOSING THE CORRECT BAND Selecting the appropriate band to use combines several factors, including the species to be banded, variability within the species, growth characteristics of the species, and band design. The following list recommends band sizes and metals based on reports from banders, compiled over the life of the ABBBS. For most species, the recommended sizes have been used on substantial numbers of birds. For some species, relatively few individuals have been banded and the size is listed with a question mark. In still other species, too few birds have been banded to justify a size recommendation and none is made. -

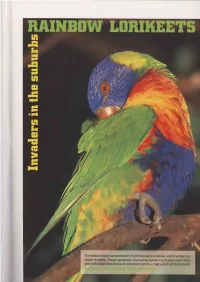

The Status and Impact of the Rainbow Lorikeet (Trichoglossus Haematodus Moluccanus) in South-West Western Australia

Research Library Miscellaneous Publications Research Publications 2005 The status and impact of the Rainbow lorikeet (Trichoglossus haematodus moluccanus) in south-west Western Australia Tamara Chapman Follow this and additional works at: https://researchlibrary.agric.wa.gov.au/misc_pbns Part of the Behavior and Ethology Commons, Biosecurity Commons, Environmental Studies Commons, Ornithology Commons, and the Population Biology Commons Recommended Citation Chapman, T. (2005), The status and impact of the Rainbow lorikeet (Trichoglossus haematodus moluccanus) in south-west Western Australia. Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development, Western Australia, Perth. Report 04/2005. This report is brought to you for free and open access by the Research Publications at Research Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in Miscellaneous Publications by an authorized administrator of Research Library. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ISSN 1447-4980 Miscellaneous Publication 04/2005 THE STATUS AND IMPACT OF THE RAINBOW LORIKEET (TRICHOGLOSSUS HAEMATODUS MOLUCCANUS) IN SOUTH-WEST WESTERN AUSTRALIA February 2005 © State of Western Australia, 2005. DISCLAIMER The Chief Executive Officer of the Department of Agriculture and the State of Western Australia accept no liability whatsoever by reason of negligence or otherwise arising from use or release of this information or any part of it. THE STATUS AND IMPACT OF THE RAINBOW LORIKEET (TRICHOGLOSSUS HAEMATODUS MOLUCCANUS) IN SOUTH-WEST WESTERN AUSTRALIA By Tamra -

Bird Guide for the Great Western Woodlands Male Gilbert’S Whistler: Chris Tzaros Whistler: Male Gilbert’S

Bird Guide for the Great Western Woodlands Male Gilbert’s Whistler: Chris Tzaros Whistler: Male Gilbert’s Western Australia PART 1. GWW NORTHERN Southern Cross Kalgoorlie Widgiemooltha birds are in our nature ® Australia AUSTRALIA Introduction The birds and places of the north-west region of the Great Western Woodlands are presented in this booklet. This area includes tall woodlands on red soils, shrublands on yellow sand plains and mallee on sand and loam soils. Landforms include large granite outcrops, Banded Ironstone Formation (BIF) Ranges, extensive natural salt lakes and a few freshwater lakes. The Great Western Woodlands At 16 million hectares, the Great Western Woodlands (GWW) is close to three quarters the size of Victoria and is the largest remaining intact area of temperate woodland in the world. It is located between the Western Australian Wheatbelt and the Nullarbor Plain. BirdLife Australia and The Nature Conservancy joined forces in 2012 to establish a long-term project to study the birds of this unique region and to determine how we can best conserve the woodland birds that occur here. Kalgoorlie 1 Groups of volunteers carry out bird surveys each year in spring and autumn to find out the species present, their abundance and to observe their behaviour. If you would like to know more visit http://www.birdlife.org.au/projects/great-western-woodlands If you would like to participate as a volunteer contact [email protected]. All levels of experience are welcome. The following six pages present 48 bird species that typically occur in four different habitats of the north-west region of the GWW, although they are not restricted to these. -

Probosciger Aterrimus), the Legacy of Landscape and Biogeographic History

Cultural diversity and meta-population dynamics in Australian palm cockatoos (Probosciger aterrimus), the legacy of landscape and biogeographic history. Miles V. Keighley Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy at the Fenner school of Environment and Society, Australian National University Photo credit: Luke Burnett © Copyright by Miles Vernon Keighley 2017 All Rights Reserved I certify that the majority of this thesis is my own original work. I have acknowledged all cases where contributions have been made by others in the Author contribution sections of each chapter. A significant contribution was made by another author who wrote the supplementary methods section of Chapter 4 (2150 words) and conducted these methods and analyses. Signed: Miles Vernon Keighley Date: September 21, 2017 Acknowledgements This thesis would not have neared completion if it wasn’t for the encouragement and support of the wonderful people surrounding me; first and foremost, my patient and infectiously enthusiastic supervisors Rob Heinsohn and Naomi Langmore. Big thank you to Christina Zdeneck for passing on so much useful knowledge about palm cockatoo vocal behaviour and accommodating us during visits to Iron Range. My family deserve much of the credit for the piece presented before you. My mum, Carol encouraged me to accept the position that I had applied for in the first place, and Dad helped to support me through my off-scholarship year. Through long phone calls, my brother James helped align my perspective keeping me functioning mentally and emotionally during fieldwork, and my other brother Matthew did the same during write-up in Denmark. I owe much to Xénia for helping support me during most of my final year, and encouraging me over the significant hurdles involved with moving overseas and a nasty back injury. -

Twenty Eight Parrot Australian Ringneck Caresheet

Australian Ringneck Parrot care! The Australian ringneck is a bird species that is found in several regions of Australia. There are a few different subspecies, each with slightly different plumage variation but all being largely green with a characteristic yellow neck ring. The subspecies are known as the twenty-eight; the Port Lincoln; the cloncurry; and the mallee. They make very good pets in the right household and are generally fairly easy to keep. Males and females both can make great pets and the sex of the bird doesn’t generally impact how good of a pet they will make. They can be quite vocal and playful. Sexual dimorphism (a visual difference between males and females) is quite subtle in Australina ringnecks (males are slightly larger than females) so DNA or endoscopic sexing can be used to tell the sex. DNA sexing is generally preferred and can be performed by taking 1 drop of blood from your parrot. Diet In the wild, Australia ringnecks eat a large variety of foods including seeds, some fruits, flowers, nectar and insects and their larvae. In captivity is best to avoid diets high in commercially produced bird seed as they are often high in fat and low in many of the major vitamins that parrots require. Feeding a high seed diet can increase the risk of obesity and other more serious problems such as lipoma (lump) formation and cardiovascular disease. Every parrot is different so for your own tailored diet plan please get in contact with us. Our general recommendations for your parrot’s diet are as follows: • 30-50% premium commercial pelleted diet suitable for medium parrots. -

Birds of Waite Conservation Reserve

BIRDS OF WAITE CONSERVATION RESERVE Taxonomic order & nomenclature follow Menkhorst P, Rogers D, Clarke R, Davies J, Marsack P, & Franklin K. 2017. The Australian Bird Guide. CSIRO Publishing. Anatidae Australian Wood Duck Chenonetta jubata R Pacific Black Duck Anas superciliosa R Phasianidae Stubble Quail Coturnix pectoralis R Brown Quail Coturnix ypsilophora V Ardeidae White-faced Heron Egretta novaehollandiae V Pelecanidae Australian Pelican Pelecanus conspicillatus V Accipitridae Black-shouldered Kite Elanus axillaris R Square-tailed Kite Lophoictinia isura R Little Eagle Hieraaetus morphnoides V Wedge-tailed Eagle Aquila audax R Brown Goshawk Accipiter fasciatus U Collared Sparrowhawk Accipiter cirrocephalus R Spotted Harrier Circus assimilis V Whistling Kite Haliastur sphenurus V Turnicidae Little Button-quail Turnix velox V Columbidae Feral Pigeon (Rock Dove) *Columba livia C Spotted Dove *Spilopelia chinensis R Common Bronzewing Phaps chalcoptera U Crested Pigeon +Ocyphaps lophotes C Cuculidae Horsfield’s Bronze Cuckoo Chalcites basalis R Fan-tailed Cuckoo Cacomantis flabelliformis R Tytonidae Eastern Barn Owl Tyto delicatula V Strigidae Southern Boobook Ninox boobook C Podargidae Tawny Frogmouth Podargus strigoides C Alcedinidae Laughing Kookaburra Dacelo novaeguineae C Falconidae Nankeen Kestrel Falco cenchroides R Australian Hobby Falco longipennis R Brown Falcon Falco berigora V Peregrine Falcon Falco peregrinus U Cacatuidae Yellow-tailed Black-Cockatoo Calyptorhynchus funereus C Galah Eolophus roseicapilla C Long-billed Corella -

Rainbow Lorikeetsin Perth Are Similar to Those Rvithin Its Natural Range

zaocsoyl 8I ueuqreg - oloqd 'erl?.rlsnv lltg uaqlrou uo{ salladsqnsI parPllol-paraql ro splq a.t?/raPluuds 'ataq I e uo{ turluup uaas:ua7 a ueurqro.lautw _ olor{d 'q ad u! paqsllqplsa^llu€u.uad ?uolaq 'srea{ luaf,aru! .a^sqtulpllsnv u! 'gaa{trol I peards-aPMlsou aql ^,\oqureuI a6Ddsnonatd I '€areusltlodo.tlaru aql puodaqIla,rppalds {pur qa?{rrol Moqurel '0002 pue ftai{ aql ,{q splq 000? tnoqe qrPar plnof, uollelndod aql ,asparf,ul .(llnsa.r Jo aler luasald aql lv l?lnllls e saqA'dllpUorllpue ssat3ns Burpaalq,azrs qllnll sp qf,nsslqsual3prpqf, paleurlsa pue u/v\ou)luo pas?q'lapou uoqPlndod e) sprrq 000e lnoq? lp palpurrlsaserr 966I Jopua aql le qlrad ur slaa{uol plr^ .eare JOraqunu lelol aql u€lrlodollau.r quad aql ol paurluor araM slaa{uol ^\oquler leql paleJrpur,{aMns aqJ 'rea^ lsPIlo JI?qpuof,as aql Fuunp sprq ar{l Jo uorleMasqoJo ^ruanba{ pue siaqunu'Eurpaa;q,saluaraJald 'rnonpq?q PooJ aql a^lasqoo1 p?lsrlua 'dpnls a.ra^slaalunlo^ 09 lnoq? aql qlr& dlaq oJ'saDadsa^rlpu ual?arql ol dla{rl sel^ Prrq aql lou lo laqlar{^\ auru.lalap 'quad ol ur laa{lrol r oqurerar{lJo ^pnls e palduold s(lJ ',{llerluEsqnspaspaDur uaasBuraq splrqJo raqurnu aql,aur] srql lnoqe lv sprrq000 I ueql alour l€ pools ,?66I 'spllq ateuns? s,BdV aql i{g 0U pu?0I uaa^qaqqlr/v1,sllou 0I u?ql arou pue spllq 7Z lo llolj e paprof,ar^a^rns e'286I uI quad ul slaaluol^ oqurpr?g ara.1araql lpql palpuqsa (gdv) plpog uolpalord arnllntuav aql ,?g6I uI SJSSYIUO'ISNIJNNOS lslu ala.{ slaalllol &oqulpl plr^/r lualaJJrpe sp slnJro lr daFaqulyaqt ul 'sPlei\\uopups0g6l-prur .loqrPIInN -

Birds on Farms

Border Rivers Birds on Farms INTRODUCTION Grain & Graze Forty-seven mixed farms within nine regions around Australia took part in BR All collecting ecological data for the biodiversityBorder section of the nationalRivers Grain Region and Graze project. Table 1 Bird Survey Statistics Farms Farms Native bird species 105 183 This factsheet outlines the results from bird surveys, conducted in Spring 2006 and Autumn 2006-2007, on five farms within the Border Rivers Region in Introduced bird species 1 6 Queensland and New South Wales. Listed Threatened Species** 7 33 NSW Listed Species 1 11 Four paddock types were surveyed, Crop, Rotation, Pasture and Remnant (see overleaf for link to methods). Although, more bird species were recorded Priority Species 3 15 in remnant vegetation, birds were also frequently observed in other land use ** State and/or Federally types (Table 2). Table 2 List of bird species recorded in each paddock in all of the 5 Border Rivers Region farms. Food Food Common Name Preference Crop Rotation Pasture RemnantCommon Name Preference Crop Rotation Pasture Remnant Grey-crowned Babbler (N) I 1 3 1 2 3 4 Brown Goshawk IC 4 Varied Sittella I 3 White-faced Heron IC 3 White-winged Triller IGF 3 3 4 5 White-necked Heron IC 3 Striped Honeyeater IN 1 3 1 3 2 3 4 Olive-backed Oriole IF 3 Blue-faced Honeyeater IN 1 1 2 3 5 Pacific Black Duck IG 3 5 Brown Honeyeater IN 5 Little Button-quail IG 3 Red-winged Parrot G 1 1 2 5 Noisy Miner IN 4 1 2 3 4 5 3 1 2 3 4 5 Wedge-tailed Eagle C 4 2 3 5 Little Friarbird IN 1 3 Brown Thornbill I -

An Endangered Species That Is Also a Pest: a Case Study of Baudin's

Journal of the Royal Society of Western Australia, 90: 33–40, 2007 An endangered species that is also a pest: a case study of Baudin’s Cockatoo Calyptorhynchus baudinii and the pome fruit industry in south-west Western Australia T F Chapman Department of Environment and Conservation, Locked Bag 104, Bentley Delivery Centre, Bentley WA 6983. [email protected] Manuscript received September 2006; accepted January 2007 Abstract Baudin’s Cockatoo Calyptorhynchus baudinii is an endangered species that is endemic to south- west Western Australia. It is also a declared pest of agriculture because it damages apple and pear (pome fruit) crops in commercial orchards. Although it is unlawful, some fruit growers shoot and kill the cockatoos to prevent fruit damage. A survey of pome fruit growers during the 2004/2005 season showed that shooting to kill can-not be justified in terms of the damage the cockatoos cause or the costs of damage control incurred by growers. Estimated loss of income to fruit damage by birds equated to 6% of farmgate income and the cost of damage control represented 2% of farmgate income. Damage levels varied significantly between individual properties and pink lady apple was the most commonly and severely damaged fruit variety. This study has shown that non-lethal scaring techniques are effective for protecting pome fruit from damage by Baudin’s Cockatoo. Keywords: Baudin’s Cockatoo, Calyptorhynchus baudinii, pome fruit industry, Western Australia Introduction A grower survey was conducted during and after the 2004/2005 pome fruit season. The purpose of the survey Baudin’s Cockatoo (Calyptorhynchus baudinii), the was to assess the attitudes of the growers toward the long-billed White-tailed Black Cockatoo, has been known conservation status of the cockatoo and to assess the cost to damage fruit in apple and pear (pome fruit) orchards of damage and damage control to growers. -

Have You Seen a Western Ground Parrot?

Fauna identification Get to know Western Australia’s fauna Have you seen a Western Ground Parrot? Unusual: The western ground parrot (Pezoporus flaviventris), known as Kyloring by the Noongar Aboriginal people, is a medium-sized, slim and mostly green parrot found in low, mid-dense heathlands in coastal areas of the South Coast of Western Australia. It spends the majority of its time on the ground and is one of only a few parrots in the world that does not nest in a hole or cavity. It is one of the first and last calls heard of the daytime birds. Secretive: Western ground parrots are almost impossible to see, not only because there are so few of them left, but also because they spend the majority of their time feeding, resting and nesting on the ground in dense vegetation. They are seldom seen on open ground, and when flushed will fly low over vegetation before flying back down into low ground cover. During the daytime they feed amongst dense plant cover. They generally only fly and call when the light is low in the hour before sunrise and the hour after sunset. Critically Endangered: Threats from fires, feral cat and fox predation and historical land clearing have caused major declines in the species’ range and population size. Photo: Abby Berryman/DPaW Where? Low coastal heathlands on the South Coast How many? Fewer than 150 – but are there more? Page 1 of 3 Having trouble figuring out if the bird you saw fits the description of the western ground parrot? Work through the key below – if you answer yes to more than one of the questions, you may have seen a western ground parrot. -

Fauna Assessment

Fauna Assessment South Capel May 2018 V4 On behalf of: Iluka Resources Limited 140 St Georges Terrace PERTH WA 6000 Prepared by: Greg Harewood Zoologist PO Box 755 BUNBURY WA 6231 M: 0402 141 197 E: [email protected] FAUNA ASSESSMENT – SOUTH CAPEL –– MAY 2018 – V4 TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY 1. INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................... 1 2. SCOPE OF WORKS ................................................................................................ 1 3. METHODS ............................................................................................................... 2 3.1 POTENTIAL FAUNA INVENTORY - LITERATURE REVIEW ................................. 2 3.1.1 Database Searches ....................................................................................... 2 3.1.2 Previous Fauna Surveys in the Area ............................................................. 2 3.1.3 Fauna of Conservation Significance .............................................................. 4 3.1.4 Invertebrate Fauna of Conservation Significance .......................................... 5 3.1.5 Likelihood of Occurrence – Fauna of Conservation Significance .................. 5 3.1.6 Taxonomy and Nomenclature ........................................................................ 6 3.2 SITE SURVEYS ....................................................................................................... 7 3.2.1 Fauna Habitat Assessment ........................................................................... -

Fauna Assessment

Fauna Assessment Medcalf Vanadium Mining Project Proposed Haul Road Audalia Resources Limited November 2017 Version 2 On behalf of: Audalia Resources Ltd c/- Botanica Consulting PO Box 2027 BOULDER WA 6432 T: 08 9093 0024 F: 08 9093 1381 Prepared by: Greg Harewood Zoologist PO Box 755 BUNBURY WA 6231 M: 0402 141 197 E: [email protected] MEDCALF VANADIUM MINING PROJECT - PROPOSED HAUL ROAD – AUDALIA RESOURCES LIMITED FAUNA ASSESSMENT – NOVEMBER 2017 – V2 TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY 1. INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................... 1 2. SCOPE OF WORKS .................................................................................. 1 3. METHODS ................................................................................................. 1 3.1 SITE SURVEYS ......................................................................................... 1 3.1.1 General Fauna Habitat Assessment ................................................ 1 3.1.2 Fauna Observations......................................................................... 2 3.2 POTENTIAL VERTEBRATE FAUNA INVENTORY ................................... 2 3.2.1 Database Searches ......................................................................... 2 3.2.2 Previous Fauna Surveys in the Area ............................................... 3 3.2.3 Existing Publications ........................................................................ 4 3.2.4 Fauna of Conservation Significance ...............................................