The Battle for Open How Openness Won and Why It Doesn’T Feel Like Victory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Opencourseware Story: New England Roots, Global Reach

08-NEB-117 NEJHE Summer 2008_Back 7/9/08 3:36 PM Page 30 FORUM: GOING DIGITAL The OpenCourseWare Story: New England Roots, Global Reach STEPHEN CARSON consortium, universities from Japan, thinking and a commitment to n April, representatives of more than 200 universities from around Spain, Korea, France, Turkey, Vietnam, addressing global challenges can the world gathered in Dalian, China, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, produce remarkable results. I the United States — plus dozens from to move forward their efforts to create MIT OpenCourseWare a global body of freely accessible course China — have already published the materials from over 6,200 courses. The OpenCourseWare movement materials spanning both cultures and has its roots in New England. The In a world of increasingly restrictive disciplines. These institutions have concept emerged in 2000 at intellectual property laws and intensi- committed to freely and openly sharing Massachusetts Institute of Technology on the Web the core teaching materials fying competition to provide for-profit where then-President Charles Vest — including syllabi, lecture notes, Web services, this movement stands charged a faculty committee with assignments and exams — from the in stark contrast to prevailing trends. answering two questions: “How is the courses they offer to their enrolled The story of this OpenCourseWare Internet going to change education?” students. Through the OpenCourseWare movement illustrates how novel and “What should MIT do about it?” A Culture of Shared Knowledge Developing a Strategy for Low-Cost Textbook Alternatives JUDY BAKER he open educational resources (OER) movement them available for use by community college students encourages the creation and sharing of free, open- and faculty. -

Learning Content 1 Next Is Now

THE FUTURE OF LEARNING CONTENT 1 NEXT IS NOW THE FUTURE OF LEARNING CONTENT Digital Textbooks, Open Content, Apple and Beyond! by Rob Reynolds, Ph.D. THE FUTURE OF LEARNING CONTENT 2 The Future of Learning Content: E-textbooks, Open Content, Apple and Beyond! By Rob Reynolds, Ph.D. Next is Now Publishing - Columbia, Missouri @nextisnow | http://nextisnow.com THETABLE FU OFTURE CON OFTEN LEARNINGTS CONTENT 3 Contents 2 Intro 01 3 10 Likely Realities for the U.S. Education Market by 2020 The Changes, 4 What Does That Mean for Textbooks and Learning Content? They Just Keep 5 5 Likely Realities for Educational Publishing and Institutions Coming 5 There Are No Deep Roots Here 7 Public Education in America Is Still Looking for its Identity 8 The Modern Textbook is a Recent Phenomenon 10 So, What’s Next? 13 Intro 02 14 A Textbook, What Is It Good For? A Textbook, 18 What’s In A Textbook (Or How Sausage Gets Made)? What Is It Good 20 How Does the Business Work? For? 23 What Are the Top 10 Obstacles for Textbook Publishers in the Future? 32 Intro 03 33 The Evolution from Centripetal to Centrifugal Content The Three Consumption Winds of 43 The Move from Content Broadcasting to Content Nanocasting Change 52 The Shift from Content as Product to Content as a Service (CaaS) 59 Intro 04 60 The Separation of Devices and Software Along Came a 64 Along Came a Tablet Tablet THETABLE FU OFTURE CON OFTEN LEARNINGTS CONTENT 4 73 Intro 05 75 True or False Open, Free, 82 Open Textbooks, the Khan Academy, and Low-cost , OpenCourseWare as Models for Free Learning -

THE GETAWAY GIRL: a NOVEL and CRITICAL INTRODUCTION By

THE GETAWAY GIRL: A NOVEL AND CRITICAL INTRODUCTION By EMILY CHRISTINE HOFFMAN Bachelor of Arts in English University of Kansas Lawrence, Kansas 1999 Master of Arts in English University of Kansas Lawrence, Kansas 2002 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December, 2009 THE GETAWAY GIRL: A NOVEL AND CRITICAL INTRODUCTION Dissertation Approved: Jon Billman Dissertation Adviser Elizabeth Grubgeld Merrall Price Lesley Rimmel Ed Walkiewicz A. Gordon Emslie Dean of the Graduate College ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my appreciation to several people for their support, friendship, guidance, and instruction while I have been working toward my PhD. From the English department faculty, I would like to thank Dr. Robert Mayer, whose “Theories of the Novel” seminar has proven instrumental to both the development of The Getaway Girl and the accompanying critical introduction. Dr. Elizabeth Grubgeld wisely recommended I include Elizabeth Bowen’s The House in Paris as part of my modernism reading list. Without my knowledge of that novel, I am not sure how I would have approached The Getaway Girl’s major structural revisions. I have also appreciated the efforts of Dr. William Decker and Dr. Merrall Price, both of whom, in their role as Graduate Program Director, have generously acted as my advocate on multiple occasions. In addition, I appreciate Jon Billman’s willingness to take the daunting role of adviser for an out-of-state student he had never met. Thank you to all the members of my committee—Prof. -

Globalization And

Web 2.0 Tools: Using Free and Open Educational Resources to Impact Learning Locally and Globally At the heart of the movement toward “ Open Educational Resources is the simple and powerful idea that the world’s knowledge is a public good and that technology in general, and the Worldwide Web in particular, ” provide an extraordinary opportunity for everyone to share, use, and re-use knowledge. — The William and Flora Hewlett Foundation Overview of Today’s Webinar 1. WHAT ARE OPEN EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES? 2. GLOBAL STATE OF ACCESS TO EDUCATION 3. OER AS A TOOL TO EQUALIZE GLOBAL EDUCATIONAL ACCESS 4. HIGH-QUALITY OER 5. NEXT STEPS WHAT ARE OPEN EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES? Development of the OER Movement 1973 Joseph Beuys founds the Free International University 2002 MIT OpenCourseWare project 2002 UNESCO adopts “OER” term 2013 Tidewater Community College Z Degree Working Definition Any type, digital or otherwise Any resource that can potentially be used for learning Copyright is either in the public domain or under an open license, such as Creative Commons Resource must be free Definition Teaching, learning, and research resources that reside in the public domain or have been released under an intellectual property license that permits their free use and re-purposing by others. Open educational resources include full courses, course materials, modules, textbooks, streaming videos, tests, software, and any other tools, materials, or techniques used to support access to knowledge. -William and Flora Hewlett Foundation Video – Why OER Matters -

Opening up Foreign Language Education with Open Educational Resources: the Case of Français Ineractif

AAUSC 2012 Volume – Issues in Language Program Direction Hybrid Language Teaching and Learning: Exploring Theoretical, Pedagogical and Curricular Issues Fernando Rubio (Editor) Joshua J. Thoms (Editor) Stacey Katz Bourns (Series Editor) Australia • Brazil • Japan • Korea • Mexico • Singapore • Spain • United Kingdom • United States 74679_fm_ptg01_i-xiv.indd 1 05/10/12 1:11 PM AAUSC 2012 Volume – Issues in © 2014, Heinle, Cengage Learning Language Program Direction: ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this work covered by the Hybrid Language Teaching copyright herein may be reproduced, transmitted, stored, or used and Learning: Exploring in any form or by any means graphic, electronic, or mechanical, Theoretical, Pedagogical and including but not limited to photocopying, recording, scanning, Curricular Issues digitizing, taping, Web distribution, information networks, or Fernando Rubio, information storage and retrieval systems, except as permitted Joshua J. Thoms and under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, Stacey Katz Bourns without the prior written permission of the publisher. Editorial Director: P. J. Boardman Publisher: Beth Kramer For product information and technology assistance, contact us at Cengage Learning Editorial Assistant: Customer & Sales Support, 1-800-354-9706 Gregory Madan For permission to use material from this text or product, Managing Media Editor: submit all requests online at cengage.com/permissions Morgen Gallo Further permissions questions can be emailed to [email protected] -

Open Educational Resources: a Review of the Literature

PRE-PRINT Open Educational Resources: A Review of the Literature Defining Open Educational Resources While a large number of competing definitions of the term “open educational resources” exist, with each focusing on different nuances of the copyright permissions structure or the different motivations for sharing open educational resources, a review of these definitions reveals a common baseline understanding. Educational materials which use a Creative Commons license or which exist in the public domain and are free of copyright restrictions are open educational resources. A rich collection of work and writing underlie this common understanding. As an emerging construct, a significant amount of the existing literature is dedicated to defining the term open educational resources and clarifying the motivations underlying this body of work (Hylén (2006), OECD (2007), Geser (2007), Atkins, Brown, and Hammond (2007), Baraniuk and Burrus (2008), Gurell and Wiley (2008), Brown and Adler (2008), and Plotkin (2010)). Mike Smith, Director of the Hewlett Foundation Education Program which provided much of the early funding for work in the area of open educational resources, wrote, “At the heart of the open educational resources movement is the simple and powerful idea that the world’s knowledge is a public good and that technology in general and the World Wide Web in particular provide an extraordinary opportunity for everyone to share, use, and reuse that knowledge” (Smith & Casserly, 2006, p. 10). Writing in 1975, MacKenzie, Postgate, and Scupham said, “Open Learning is an imprecise phrase to which a range of meanings can be, and is, attached. It eludes Page 1 of 33 PRE-PRINT definition. -

Student Loses Lawsuit Against Rice

.«-• i i-V Rice Vol. LXXXVIII, Issue No. 30 SINCE 1916 Friday, May 25, 2001 1 Student loses lawsuit against Rice by Leslie Liu spectives on genetics taught last fall. She appealed the decision to THRESHER EDITORIAL STAFF The paper in question was copied President Malcolm Gillis and the from a Web site. She was suspended interim assistant dean for student A student found guilty of plagia- for two semesters and failed the judicial programs Ron Sass, chair of rism by the Honor Council did not course after her Honor Council case. the Ecology and Evolutionary Biol- graduate this year despite her law- During the case, Bangale claimed ogy department. Both upheld the suit against Rice trying to force the that the plagiarized paper — which Honor Council's decision, leading institution to grant her a degree. was submitted by e-mail to one of her to file suit against Rice. Baker College senior Anita the professors in the class — was If she had graduated, she would Bangale's lawyer argued in court that not the paper she turned in at all. have attended Baylor College of the evidence gathered by the Honor She said she wrote an entirely differ- Medicine this fall. As it is, she can- Council was not clear and convincing, ent paperand submitted a paper copy not attend classes without a degree. and that the judge should grant a tem- to her anthropology professors.- Now the case will be brought porary injunction allowing her to Neither professor received the back before the court in a hearing in graduate May 12, according to an ar- hard copy of the paper. -

Making Higher Education More Affordable, One Course Reading at a Time: Academic Libraries As Key Advocates for Open Access Textbooks and Educational Resources

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research John Jay College of Criminal Justice 2013 Making Higher Education More Affordable, One Course Reading at a Time: Academic Libraries as Key Advocates for Open Access Textbooks and Educational Resources Karen Okamoto John Jay College of Criminal Justice, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/jj_pubs/103 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] 1 This is an electronic version of an article published in Public Services Quarterly, 2013, 9(4), pp.267-283, available online at: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/15228959.2013.842397. Making Higher Education More Affordable, One Course Reading at a Time: Academic Libraries as Key Advocates for Open Access Textbooks and Educational Resources Karen Okamoto Open access textbooks (OATs) and educational resources (OERs) are being lauded as a viable alternative to costly print textbooks. Some academic libraries are joining the OER movement by creating guides to open repositories. Others are promoting OATs and OERs, reviewing them, and even helping to create them. This article analyzes how academic libraries are currently engaged in open access textbook and OER initiatives. By drawing on examples of library initiatives across the United States, the author illustrates how libraries are facilitating the adoption and implementation of these affordable resources. Introduction Open access textbooks (OATs) and open educational resources (OERs) are being lauded as affordable alternatives to costly print textbooks. -

PLAYLIST 16.0 - AUG 2020 - FEB 2021 900 Songs, 2.3 Days, 5.50 GB

Page 1 of 17 INDIGO FM - PLAYLIST 16.0 - AUG 2020 - FEB 2021 900 songs, 2.3 days, 5.50 GB Name Time Album Artist 1 The Bond - with intro 4:35 Adrian Clark 2 Kelly Watch The Stars 3:46 Electrospective Air 3 I Believe To My Soul 4:28 Rare & Well Done D1 (Rare) Al Kooper 4 Rib Cage 3:36 Alana Wilkinson Alana Wilkinson 5 Good For You 3:37 Good For You Alana Wilkinson 6 Hard Rock Gold 4:33 Hidden Hand Alaska String Band 7 Workin' Man Blues 3:57 Working Man Albert Cummings 8 The Barrel 4:53 Uncut 2020.01 The Sound of 2019 - 15 Tracks of the Year's… Aldous Harding 9 Before Too Long 3:04 Alex Cameron 104:05 4:07 Alex Lleo 11 Everybody's Laughing 3:50 Watching Angels Mend Alex Lloyd 12 I Think You're Great 3:47 I Think You're Great Alex the Astronaut 13 Split The Sky 4:07 Split the Sky Alex the Astronaut 14 Steppenwolf Express 3:47 On The Move To Chakino Alexander Tafintsev 15 The Captain (Live From Inside) 3:40 Live From Inside Ali Barter 16 I Won't Lie (Live From Inside) 3:49 Live From Inside Ali Barter 17 Ticket To Heaven feat. Thelma Plum 4:17 Alice Ivy 18 Don't Sleep 3:24 Alice Ivy 19 King Of The World 3:45 triple j Unearthed Alice Night 20 Rainbow Song 3:59 triple j Unearthed Alice Night 21 Friends With Feelings 4:15 Alice Skye 22 Grand Ideas 3:12 Alice Skye 23 Sacred 4:44 Amaringo 24 Endangered Man 4:35 Rituals Amaya Laucirica 25 I Said Hi 2:50 Love Monster Amy Shark 26 Never Coming Back 3:14 Love Monster Amy Shark 27 Me & Mr. -

Joint Task Force on Textbook and Reader Affordability

Report of the Joint Task Force on Textbook and Reader Affordability University of California, Berkeley June 15, 2010 Table of Contents Executive Summary and Key Recommendations........................................................................3 Work of the Task Force Need for a Task Force.............................................................................................................5 Formation of the Task Force...................................................................................................5 Charge of the Task Force........................................................................................................6 Process of the Task Force .......................................................................................................6 Current Campus Processes Instructors ...............................................................................................................................6 Textbooks................................................................................................................................7 Course Reserves......................................................................................................................8 Readers....................................................................................................................................8 Students...................................................................................................................................9 Alternative Formats for Students with Disabilities...............................................................10 -

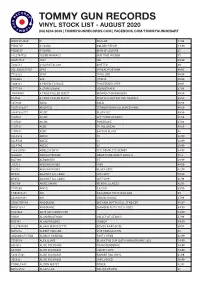

Vinyl Stock List - August 2020 (03) 6234 2039 | Tommygunrecords.Com | Facebook.Com/Tommygunhobart

TOMMY GUN RECORDS VINYL STOCK LIST - AUGUST 2020 (03) 6234 2039 | TOMMYGUNRECORDS.COM | FACEBOOK.COM/TOMMYGUNHOBART WARPLP302X !!! WALLOP 47.99 PIE027LP #1 DADS GOLDEN REPAIR 44.99 PIE005LP #1 DADS MAN OF LEISURE 35 8122794723 10,000 MANIACS OUR TIME IN EDEN 45 SSM144LP 1927 ISH 39.99 7202581 24 CARAT BLACK GHETTO 69 USI_B001655701 2PAC 2PACALYPSE NOW 49.95 7783828 2PAC THUG LIFE 49.99 FWR004 360 UTOPIA 49.99 5809181 A PERFECT CIRCLE THIRTEENTH STEP 49.95 6777554 A STAR IS BORN SOUNDTRACK 67.99 JIV41490.1 A TRIBE CALLED QUEST MIDNIGHT MARAUDERS 49.99 R14734 A TRIBE CALLED QUEST PEOPLE'S INSTINCTIVE TRAVELS 69.99 5351106 ABBA GOLD 49.99 19075850371 ABORTED TERRORVISION COLOURED VINYL 49.99 88697383771 AC/DC BLACK ICE 49.99 5107611 AC/DC LET THERE BE ROCK 41.99 5107621 AC/DC POWERAGE 47.99 5107581 ACDC 74 JAIL BREAK 49.99 5107651 ACDC BACK IN BLACK 45 XLLP313 ADELE 19 32.99 XLLP520 ADELE 21 32.99 XLLP740 ADELE 25 29.99 1866310761 ADOLESCENTS THE COMPLETE DEMOS 34.95 LL030LP ADRIAN YOUNGE SOMETHING ABOUT APRIL II 52.8 M27196 AEROSMITH ST 39.99 J12713 AFGHAN WHIGS 1965 49.99 P18761 AFGHAN WHIGS BLACK LOVE 42.99 OP048 AGAINST ALL LOGIC 2012-2017 59.99 OP053 AGAINST ALL LOGIC 2017-2019 61.99 S80109 AIMEE MANN MENTAL ILLNESS 42.95 7747280 AINTS 5,6,7,8,9 39.99 1.90296E+11 AIR CASANOVA 70 PIC DISC RSD 40 2438488481 AIR VIRGIN SUICIDE 37.99 SPINE799189 AIRBOURNE BREAKIN OUTTA HELL STND EDT 45.95 NW31135-1 AIRBOURNE DIAMOND CUTS THE B SIDES 44.99 FN279LP AK79 40TH ANNIV EDT 63.99 VS001 ALAN BRAUFMAN VALLEY OF SEARCH 47.99 M76741 ALAN PARSONS I -

Suicide the Forever Decision by Dr. Paul G. Quinnett

SUICIDE The Forever Decision New 3rd Edition By Dr. Paul G. Quinnett Dr. Quinnett is a clinical psychologist and the Director of the QPR Institute, an educational organization dedicated to preventing suicide. He has worked with suicidal people and survivors of suicide for more than 35 years. Author of seven books and an award- winning journalist, he is also a Clinical Assistant Professor in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Science at the University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, Washington. Compliments of the QPR Institute Suicide: the Forever Decision For those thinking about suicide and for those who know, love and counsel them. DISCLAIMER Both author and publisher wish the reader to know that this book does not offer mental health treatment, and in no way should be considered a substitute for consultation with a professional. The identities of the people written about in this book have been carefully disguised in accordance with professional standards of confidentiality and in keeping with their rights to privileged communication with the author. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Introduction ...........................................................................5 CHAPTER1 You Don't Have to Be Crazy...................................................7 CHAPTER2 An Idea That Kills ................................................................ 11 CHAPTER3 Don't I Have a Right to Die?................................................. 13 CHAPTER4 Are You Absolutely Sure?...................................................