Cliff Swallow Petrochelidon Pyrrhonota Bottles Made of Mud Pellets and Stuck to Bridges and Buildings, Cliff Swallow Nests Are P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aves: Hirundinidae)

1 2 Received Date : 19-Jun-2016 3 Revised Date : 14-Oct-2016 4 Accepted Date : 19-Oct-2016 5 Article type : Original Research 6 7 8 Convergent evolution in social swallows (Aves: Hirundinidae) 9 Running Title: Social swallows are morphologically convergent 10 Authors: Allison E. Johnson1*, Jonathan S. Mitchell2, Mary Bomberger Brown3 11 Affiliations: 12 1Department of Ecology and Evolution, University of Chicago 13 2Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Michigan 14 3 School of Natural Resources, University of Nebraska 15 Contact: 16 Allison E. Johnson*, Department of Ecology and Evolution, University of Chicago, 1101 E 57th Street, 17 Chicago, IL 60637, phone: 773-702-3070, email: [email protected] 18 Jonathan S. Mitchell, Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Michigan, 19 Ruthven Museums Building, Ann Arbor, MI 48109, email: [email protected] 20 Mary Bomberger Brown, School of Natural Resources, University of Nebraska, Hardin Hall, 3310 21 Holdrege Street, Lincoln, NE 68583, phone: 402-472-8878, email: [email protected] 22 23 *Corresponding author. 24 Data archiving: Social and morphological data and R code utilized for data analysis have been 25 submitted as supplementary material associated with this manuscript. 26 27 Abstract: BehavioralAuthor Manuscript shifts can initiate morphological evolution by pushing lineages into new adaptive 28 zones. This has primarily been examined in ecological behaviors, such as foraging, but social behaviors 29 may also alter morphology. Swallows and martins (Hirundinidae) are aerial insectivores that exhibit a This is the author manuscript accepted for publication and has undergone full peer review but has not been through the copyediting, typesetting, pagination and proofreading process, which may lead to differences between this version and the Version of Record. -

The Evolution of Nest Construction in Swallows (Hirundinidae) Is Associated with the Decrease of Clutch Size

© Biologiezentrum Linz/Austria; download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Linzer biol. Beitr. 38/1 711-716 21.7.2006 The evolution of nest construction in swallows (Hirundinidae) is associated with the decrease of clutch size P. HENEBERG A b s t r a c t : Variability of the nest construction in swallows (Hirundinidae) is more diverse than in other families of oscine birds. I compared the nest-building behaviour with pooled data of clutch size and overall hatching success for 20 species of swallows. The clutch size was significantly higher in temperate cavity-adopting swallow species than in species using other nesting modes including species breeding in evolutionarily advanced mud nests (P<0.05) except of the burrow-excavating Bank Swallow. Decrease of the clutch size during the evolution of nest construction is not compensated by the increase of the overall hatching success. K e y w o r d s : Hirundinidae, nest construction, clutch size, evolution Birds use distinct methods to avoid nest-predation: active nest defence, nest camouflage and concealment or sheltered nesting. While large and powerful species prefer active nest-defence, swallows and martins usually prefer construction of sheltered nests (LLOYD 2004). The nests of swallows vary from natural cavities in trees and rocks, to self-exca- vated burrows to mud retorts and cups attached to vertical faces. Much attention has been devoted to the importance of controlling for phylogeny in com- parative tests (HARVEY & PAGEL 1991), including molecular phylogenetic studies of swallows (WINKLER & SHELDON 1993). Interactions between the nest-construction va- riability and the clutch size, however, had been ignored. -

Cave Swallow: Colorado’S Stealthiest Vagrant

Deininger; DFO: Denver Field Ornithologists; CD: Coen Dexter; ED: Edward Donnan; JD: John Drummond; FD: Florence Duty; LE: Lisa Edwards; EBE: E.B. Ellis; DF: Dick Filby; AF: Andrew Floyd; HF: Hannah Floyd; TF: Ted Floyd; NF: Nelson Ford; DG: Den- nis Garrison; MG: Mel Goff; BG: Bryan Guarente; BBH: BB Hahn; DH: Dona Hilkey; KH: Kathy Horn; MJ: Margie Joy; BK: Bill Kaempfer; TK: Tim Kalbach; MK: Mary Keithler; JK: Joey Kellner; BKe: Ben Kemena; RK: Richard Kendall; LK: Loch Kilpat- rick; HK: Hugh Kingery; UK: Urling Kingery; KK: Ken Kinyon; EK: Elena Klaver; GK: Gary Koehn; CK: Connie Kogler; NKr: Nick Komar; NKe: Nic Korte; SL: Steve Larson; LL: Lin Lilly; TL: Tom Litteral; FL: Forrest Luke; BM: Bill Maynard; DM: Dan Maynard; TMc: Tom McConnell; NM: Nancy Merrill; KMD: Kathy Mihm-Dunning; RM: Rich Miller; JM: Jeannie Mitchell; SM: Steve Mlodinow; TMo: Tresa Moulton; PPN: Paul & Polly Neldner; JN: Jim Nelson; KN: Kent Nelson; CN: Christian Nunes; BP: Brandon Percival; MP: Mark Peterson; NP: Nathan Pieplow; M&PP: Mike & Pat Pilburn; PP: Pete Plage; SP: Suzi Plooster; BPr: Bill Prather; IP: Inez Prather; SRd: Scott Rashid; SRo: Saraiya Ruano; RR: Rick Reeser; PSS: Pearle Sandstrom-Smith; BSc: Bill Schmoker; JKS: Jim & Karen Schmoker; LS: Larry Semo; SS: Scott Severs; KS: Kelly Shipe; DS: David Silverman; CS: Clif Smith; AS: Andy Spellman; GS: George Steele; BSt: Brad Steger; CS: Cara Stiles; JS: Jane Stulp; DT: Dave Trappett; VT: Van Truan; JV: John Vanderpoel; GW: Glenn Walbek; DW: David Wald; TW: Tom Wilberding; CW: Cole Wild; LPW: Lisa & Paul Williams; BW: Brenda Wright; MY: Mark Yaeger liTerATure CiTed NWSFO (National Weather Service Forecast Office). -

Effects of Bridge Design on Placement and Shape of Cliff Swallow (Petrochelidon Pyrrhonota) Nests in Southern Arkansas

Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science Volume 67 Article 42 2013 Effects of Bridge Design on Placement and Shape of Cliff wS allow (Petrochelidon pyrrhonota) Nests in Southern Arkansas R. Tumlison Henderson State University, [email protected] K. Kendall Henderson State University Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/jaas Part of the Zoology Commons Recommended Citation Tumlison, R. and Kendall, K. (2013) "Effects of Bridge Design on Placement and Shape of Cliff wS allow (Petrochelidon pyrrhonota) Nests in Southern Arkansas," Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science: Vol. 67 , Article 42. Available at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/jaas/vol67/iss1/42 This article is available for use under the Creative Commons license: Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-ND 4.0). Users are able to read, download, copy, print, distribute, search, link to the full texts of these articles, or use them for any other lawful purpose, without asking prior permission from the publisher or the author. This General Note is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science, Vol. 67 [2013], Art. 42 Effects of Bridge Design on Placement and Shape of Cliff Swallow (Petrochelidon pyrrhonota) Nests in Southern Arkansas R. Tumlison* and K. Kendall Department of Biology, Henderson State University, Arkadelphia, AR 71999 *Correspondence: [email protected] Running title: Bridge Design Affects Shape of Cliff Swallow Nests The Cliff Swallow (Petrochelidon pyrrhonota) is identifiable by its orange rump, pale forehead patch, and square tail. -

Cliff Swallow Petrochelidon Pyrrhonota

Natural Heritage Cliff Swallow & Endangered Species Petrochelidon pyrrhonota Program State Status: None www.mass.gov/nhesp Federal Status: None Massachusetts Division of Fisheries & Wildlife SPECIES DESCRIPTION: The Cliff Swallow is small, pointed-winged, aerial insectivore with a square tail, orange rump, and chestnut-colored throat. They historically nested in large colonies on cliff faces in the western United States, but are now found across much of North America, nesting in the east primarily on artificial surfaces such as bridges, culverts, and buildings. DISTRIBUTION AND ABUNDANCE: Cliff Swallows have been steadily declining as breeders in Massachusetts and are now relegated primarily to small colonies in Berkshire, Franklin, and northern Essex Counties. In the first Massachusetts Breeding Bird Atlas, the mountainous western areas of the state hosted fair numbers of Cliff Swallow colonies, both on natural cliffs Figure 2: Massachusetts Breeding Bird Survey results, 1966-2009. and on human structures such as barns and bridges. The Connecticut River Valley had no shortage of such due to heavy infiltration of House Sparrows. Swallows structures but had only 21% occupancy by blocks, likely were present in similar proportions across the Worcester and Lower Worcester Plateau regions, but Coastal Plains records were almost entirely restricted to the northern parts of the region. Only a handful of Cliff Swallow colonies were reported in the Lowlands and Cape Cod. By Atlas 2, no Cliff Swallows were found in Norfolk, Bristol, Plymouth, Barnstable, or Nantucket Counties. The species entirely vacated the Worcester Plateau as well. The Cliff Swallows that were found in Massachusetts during Atlas 2 covered less than half the breeding footprint of Atlas I and were largely located in the west, where suitable nesting sites (i.e., old barns) could still be found, along with a few sites in northern Essex County. -

TREE SWALLOW Tachycineta Bicolor Tree Swallows Are the Only Swallows to Be Seen All Year in the Sacramento Region

TREE SWALLOW Tachycineta bicolor Tree swallows are the only swallows to be seen all year in the Sacramento region. A few winter here; others come to join them early in the spring. They are about sparrow-length but slimmer. The male is steel blue on top, white underneath. Tree swallows like wooded areas near streams. They can be seen skimming close to the water scooping up insects. Usually a hole in a tree trunk is chosen for a nest and lined with grass, leaves and feathers. The violet green swallow, a bird with similar colors but with white around the sides of the rump, is found here in warm weather. CLIFF SWALLOW Petrochelidon pyrrhonota Cliff swallows, famous for their annual return to San Juan Capistrano, likewise return to the Sacramento region within a few days of the same date each year. Wherever a bridge or culvert houses a colony of these swallows, the same kind of homecoming takes place each spring. Cliff swallows are identified by their buff foreheads, orange rumps, and square tails. They fly with long sweeping glides and steep climbs, catching flying insects on the wing. The bulb-shaped nests, hung under bridges, highway overpasses and eaves of buildings, are built entirely of mud. Flocks of cliff swallows can be seen around puddles gathering mud in their bills. When disturbed by an intruder or when flying over feeding grounds, the birds utter a squeaky, guttural sound. BARN SWALLOW Hirundo rustica Here is a bird with a real “swallow tail” outfit. In fact, it is our only swallow with a deeply forked tail. -

The Oriole.Indd 1 5/21/08 9:18:21 AM 2 the ORIOLE Vols

THE ORI O LE Quarterly Journal of the Georgia Ornithological Society Volumes 70 – 71 January – December 2005 – 2006 Numbers 1 – 4 TWO CAVE SWALLOWS AND ONE NORTHERN ROUGH- WINGED SWALLOW ON THE DECEMBER 2002 MACON CHRISTMAS BIRD COUNT Paul Johnson 901 Santa Fe Trail, Macon, GA 31220 Email: [email protected] On 14 December 2002, during the annual Macon Christmas Bird Count (CBC), Walt Bowman, Nancy Gobris, Ty Ivey, Larry Ross, and I observed two Cave Swallows (Petrochelidon fulva) at the Macon Dump in Bibb County, Georgia, between 1500 and 1530 hours. Our team also noted one Northern Rough-winged Swallow (Stelgidopteryx serripennis) at the same location. Around 0800 hours, Ty Ivey, Walt Bowman, and Nancy Gobris found a Northern Rough-winged Swallow at the Macon Water Treatment Site, about 2.5 km (1.5 miles) from the Macon Dump. Because it was possible that our team saw the same individual swallow twice, we reported just one Northern Rough- winged Swallow within our CBC data. We entered the Macon Dump shortly after 1500 hours. The weather was overcast, with a strong westerly wind and cold temperatures. The CBC low temperature on 14 December was 4 C (40 F) and the high was 8 C (46 F). I first noticed a swallow over the lake from our moving vehicle. I saw the light rump and believed it was a Cliff Swallow (Petrochelidon pyrrhonota). As we watched the swallow with our binoculars, we began to consider the possibility of a Cave Swallow. At this point we noticed two other swallows, a second Petrochelidon and a Northern Rough-winged Swallow. -

Kanha Survey Bird ID Guide (Pdf; 11

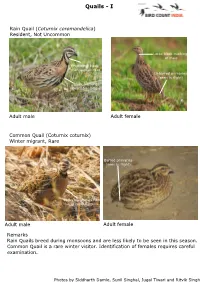

Quails - I Rain Quail (Coturnix coromandelica) Resident, Not Uncommon Lacks black markings of male Prominent black markings on face Unbarred primaries (seen in flight) Black markings (variable) below Adult male Adult female Common Quail (Coturnix coturnix) Winter migrant, Rare Barred primaries (seen in flight) Lacks black markings of male Rain Adult male Adult female Remarks Rain Quails breed during monsoons and are less likely to be seen in this season. Common Quail is a rare winter visitor. Identification of females requires careful examination. Photos by Siddharth Damle, Sunil Singhal, Jugal Tiwari and Ritvik Singh Quails - II Jungle Bush-Quail (Perdicula asiatica) Resident, Common Rufous and white supercilium Rufous & white Brown ear-coverts supercilium and Strongly marked brown ear-coverts above Rock Bush-Quail (Perdicula argoondah) Resident, Not Uncommon Plain head without Lacks brown ear-coverts markings Little or no streaks and spots above Remarks Jungle is typically more common than Rock in Central India. Photos by Nikhil Devasar, Aseem Kumar Kothiala, Siddharth Damle and Savithri Singh Crested (Oriental) Honey Buzzard (Pernis ptilorhynchus) Resident, Common Adult plumages: male (left), female (right) 'Pigeon-headed', weak bill Weak bill Long neck Long, slender Variable streaks and and weak markings below build Adults in flight: dark morph male (left), female (right) Confusable with Less broad, rectangular Crested Hawk-Eagle wings Rectangular wings, Confusable with Crested Serpent not broad Eagle Long neck Juvenile plumages Confusable -

American Swallow Bug, Oeciacus Vicarius Horvath (Hemiptera: Cimicidae), in Hirundo Rustica and Petrochelidon Pyrrhonota Nests in West Central Colorado

Great Basin Naturalist Volume 47 Number 2 Article 24 4-30-1987 American swallow bug, Oeciacus vicarius Horvath (Hemiptera: Cimicidae), in Hirundo rustica and Petrochelidon pyrrhonota nests in west central Colorado Thomas Orr Mesa College, Grand Junction, Colorado Gary McCallister Mesa College, Grand Junction, Colorado Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/gbn Recommended Citation Orr, Thomas and McCallister, Gary (1987) "American swallow bug, Oeciacus vicarius Horvath (Hemiptera: Cimicidae), in Hirundo rustica and Petrochelidon pyrrhonota nests in west central Colorado," Great Basin Naturalist: Vol. 47 : No. 2 , Article 24. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/gbn/vol47/iss2/24 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Western North American Naturalist Publications at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Basin Naturalist by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. AMERICAN SWALLOW BUG, OECIACUS VICARIUS HORVATH (HEMIPTERA: CIMICIDAE), IN HIRUNDO RUSTICA AND PETROCHELIDON PYRRHONOTA NESTS IN WEST CENTRAL COLORADO Thomas Orr' and Gary McCallister' Abstract —Oeciacus vicarius bed hugs were collected i'rom 32% ot'Hirundo ni.stica nests and 83% ofPetroclielidon pyrrhonota nests on bridges in western Colorado in December 1984. A total of 409 bugs (158 adults and 251 juveniles) were counted in 47 nests, two months after the hosts had departed for the winter. Two regular avian visitors to the Colorado lected into 70% ethanol. Mites, ticks, spiders, River system in west central Colorado are the moths, and dermestids were included, but cliff swallow, Petrochelidon pyrrhonota, and the most abundant species was Oeciacus vi- the barn swallow, Hirundo rustica. -

Swallows Nesting in Nuisance Locations

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Swallows Nesting in Nuisance Locations Cliff swallows present a high degree of intraspecific brood parasitism. Individuals often lay eggs in other individuals’ nests within the same colony. It has been observed that some parasitic swallows have even tossed out their neighbors’ eggs and replaced them with their own offspring. Parasitized swallows had lower success in fledging their own chicks. This behavior has been adapted to increase the parasitic swallow’s offspring’s success by passing on the burden of taking care of chicks to another individual. Solitary Barn swallow at Anahuac National Wildlife Refuge. Tim Ludwick/USFWS There are eight species of swallows that regularly breed in North America: the Bank swallow, Barn swallow, Cave swallow, Cliff swallow, Northern Rough-winged swallow, Purple martin, Tree swallow, and Violet-green swallow. Natural History: After migrating north from their wintering grounds, mostly in Central America, Cliff and Barn swallows often nest on cliffs, canyons, bridges, and eaves of buildings. Swallows may construct an entirely new Cliff swallows constructing their nests at Kern National nest or they may use old nests, building off of traces Wildlife Refuge. Tim Ludwick/USFWS of mud where an old nest used to be. The breeding season for swallows lasts from March through Ecological Value of Swallows: September. They often produce two clutches per Swallows provide us with an ecological service as year, with a clutch size of 3-5 eggs. Eggs incubate insect controllers. They particularly consume between 13-17 days and fledge after 18-24 days. swarming insects such as bees, wasps, flies, However, chicks return to the nest after fledging for damselflies, moths, grasshoppers, crickets, and several weeks before they leave the nest for good. -

Cliff Swallow Hirundo Pyrrhonota

Cliff Swallow Hirundo pyrrhonota Breeding by the Cliff Swallow is limited to areas that offer open areas for foraging, ver tical surfaces with an overhang for nest sites, and mud for nesting material (Emlen 1954). In Vermont, the species is most fre quently encountered in open farmlands near large barns or other buildings suitable for nest sites. The species has been found nest ing in forested areas, such as the base lodge at Jay Peak, where adjacent ski trails pre sumably provide the prerequisite open for aging areas. Although the eaves of buildings provide by far the most common sites in Vermont, the species has been recorded (Samuel 1971). Twenty-seven dates for nest nesting under highway bridges, on one-story lings in Vermont range from June 11 to Au shopping malls, on houses, and inside sheds. gust 12. The nestling period lasts about 24 Originally the species nested on cliffs, but days (Samuel 1971). There are only two re there has been no reference to cliff nesting ported dates for dependent young for Ver in Vermont since Cutting (1884). mont-July 16 and August 8; egg and nest Cliff Swallows are frequently conspicuous ling dates indicate that dates for dependent as they hawk insects over hayfields and young should range from the first week of bodies of water. Groups of these swallows July to the fourth week of August. The au gathering mud, all with wings held high tumn migration peaks in August. A few Cliff over their backs, also call attention to the Swallows are seen during September each species. -

No Effect of Insect Abundance on Nestling Survival Or Mass for Three Aerial Insectivores

VOLUME 12, ISSUE 2, ARTICLE 19 Imlay, T. L., H. A. R. Mann, and M. L. Leonard. 2017. No effect of insect abundance on nestling survival or mass for three aerial insectivores. Avian Conservation and Ecology 12(2):19. https://doi.org/10.5751/ACE-01092-120219 Copyright © 2017 by the author(s). Published here under license by the Resilience Alliance. Research Paper No effect of insect abundance on nestling survival or mass for three aerial insectivores Tara L. Imlay 1, Hilary A. R. Mann 1,2 and Marty L. Leonard 1 1Biology Department, Dalhousie University, Halifax, NS, Canada, 2Wildlife Preservation Canada, Guelph, ON, Canada ABSTRACT. Swallows, along with other aerial insectivores, are experiencing steep population declines. Decreased insect abundance has been implicated as a potential cause of the decline. However, to determine if there is a guild-level effect of reduced insect abundance on swallows, research is needed to examine relationships between insect abundance and breeding success for multiple species. The goal of our study was two-fold. First, we determined if insect abundance during nestling rearing varied with breeding phenology for three species of swallows, Barn (Hirundo rustica), Cliff (Petrochelidon pyrrhonota), and Tree Swallows (Tachycineta bicolor), such that swallows breeding when insects are abundant have greater success. Then we determined if insect abundance was related to nestling survival and mass (as a proxy for postfledgling survival). We collected insects daily at each of three study sites during the breeding season, monitored swallow nests to determine breeding phenology and success, and weighed nestlings at or just prior to the peak of rapid nestling growth to determine mass.