Cave Swallow: Colorado’S Stealthiest Vagrant

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aves: Hirundinidae)

1 2 Received Date : 19-Jun-2016 3 Revised Date : 14-Oct-2016 4 Accepted Date : 19-Oct-2016 5 Article type : Original Research 6 7 8 Convergent evolution in social swallows (Aves: Hirundinidae) 9 Running Title: Social swallows are morphologically convergent 10 Authors: Allison E. Johnson1*, Jonathan S. Mitchell2, Mary Bomberger Brown3 11 Affiliations: 12 1Department of Ecology and Evolution, University of Chicago 13 2Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Michigan 14 3 School of Natural Resources, University of Nebraska 15 Contact: 16 Allison E. Johnson*, Department of Ecology and Evolution, University of Chicago, 1101 E 57th Street, 17 Chicago, IL 60637, phone: 773-702-3070, email: [email protected] 18 Jonathan S. Mitchell, Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Michigan, 19 Ruthven Museums Building, Ann Arbor, MI 48109, email: [email protected] 20 Mary Bomberger Brown, School of Natural Resources, University of Nebraska, Hardin Hall, 3310 21 Holdrege Street, Lincoln, NE 68583, phone: 402-472-8878, email: [email protected] 22 23 *Corresponding author. 24 Data archiving: Social and morphological data and R code utilized for data analysis have been 25 submitted as supplementary material associated with this manuscript. 26 27 Abstract: BehavioralAuthor Manuscript shifts can initiate morphological evolution by pushing lineages into new adaptive 28 zones. This has primarily been examined in ecological behaviors, such as foraging, but social behaviors 29 may also alter morphology. Swallows and martins (Hirundinidae) are aerial insectivores that exhibit a This is the author manuscript accepted for publication and has undergone full peer review but has not been through the copyediting, typesetting, pagination and proofreading process, which may lead to differences between this version and the Version of Record. -

Cave Swallow Range Continues to Expand

CaveSwallow range continues to expand Cliff and Barn swallows may be displaced from their former nesting sites by the continued expansion of the Cave Swallow Paul C. Palmer Swallows was noted in American Birds Nancy and I set out in the afternoon to tin and many others have docu- in 1984 not only in Jim Hogg, Brooks, test that hypothesis.Within two hours INCEmentedTHE a phenomenalEARLY 1970S, expansion R.F.MAR-of and Duval counties,but in Kleberg,one we found mixed breeding coloniesof the rangeof the Cave Swallow(Hirundo of the counties of the Texas Coastal Barn and Cave swallows at five locations fulva) in Texas. That range expansion Bend. Steve Labuda of Santa Ana Na- along US 77 in Kleberg and Kenedy hasbeen accompaniedby a pronounced tional Wildlife Refuge discoveredand counties. breakdownof the former segregationof ThomasPincelli reporteda nestingcol- US 77 is the only north-south h•gh- the speciesfrom othersof its genus;most ony, including all three species,under a way through thosecounties. The swal- of the new nesting colonies have in- concrete bridge on SH 285 at Salado low colonies were located under con- cludedBarn Swallows(Hirundo rustica) Creek, west of Riviera in southernKle- crete bridgesalong the highwayand •n and many have included Cliff Swallows berg County (Lasley and Sexton 1984; concrete culverts under it. One of the (H irundopyrrhonota ) (Oberholser1974; Pincelli per& comm.). Cave Swallows sites was at Ebanito Creek, 3.5 kdo- Martin 1974; Martin and Martin 1978; returned to that site in 1985 and 1986, meters south of Ricardo. Another was Kutac 1982). The new nestingsites have despite destruction of the original 8.75 kilometers south of Ricardo. -

The Evolution of Nest Construction in Swallows (Hirundinidae) Is Associated with the Decrease of Clutch Size

© Biologiezentrum Linz/Austria; download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Linzer biol. Beitr. 38/1 711-716 21.7.2006 The evolution of nest construction in swallows (Hirundinidae) is associated with the decrease of clutch size P. HENEBERG A b s t r a c t : Variability of the nest construction in swallows (Hirundinidae) is more diverse than in other families of oscine birds. I compared the nest-building behaviour with pooled data of clutch size and overall hatching success for 20 species of swallows. The clutch size was significantly higher in temperate cavity-adopting swallow species than in species using other nesting modes including species breeding in evolutionarily advanced mud nests (P<0.05) except of the burrow-excavating Bank Swallow. Decrease of the clutch size during the evolution of nest construction is not compensated by the increase of the overall hatching success. K e y w o r d s : Hirundinidae, nest construction, clutch size, evolution Birds use distinct methods to avoid nest-predation: active nest defence, nest camouflage and concealment or sheltered nesting. While large and powerful species prefer active nest-defence, swallows and martins usually prefer construction of sheltered nests (LLOYD 2004). The nests of swallows vary from natural cavities in trees and rocks, to self-exca- vated burrows to mud retorts and cups attached to vertical faces. Much attention has been devoted to the importance of controlling for phylogeny in com- parative tests (HARVEY & PAGEL 1991), including molecular phylogenetic studies of swallows (WINKLER & SHELDON 1993). Interactions between the nest-construction va- riability and the clutch size, however, had been ignored. -

Head-Scratching Method in Swallows Depends on Behavioral Context

SHORT COMMUNICATIONS 679 shoulder-spot display during their observations of behavior in partridges. In all cases that I observed, the shoulder spot appeared to be a fear or flight intention display as described by Lumsden (1970). However, the display seemed secondary in importance compared to vocalizations and “tail flicking” during periods of extreme alarm. Examination of the shoul- der spot of a partridge confirmed the realignment of white underwing coverts to the top of the wing in the patagial region. The manipulation by the bird of underwing feathers appeared to be identical to that of Ruffed Grouse (Bonusa umbellus)(Garbutt 198 1). Since “display” implies actual communication between individuals further investigation is needed to de- termine if, in fact, the shoulder spot actually is serving a communication function in Gray Partridge. The shoulder spot in Gray Partridges and the display seen in grouse are morphologically similar. Lumsden (1970) concluded that the widespread occurrence of this display among grouse indicated it appeared relatively early in evolution. The morphological and behavioral similarities between the display in grouse and partridges suggest that the shoulder spot may have evolved even earlier. Since this is an escape behavior, and since many species of partridges and pheasants are difficult to observe in the wild, it may have been overlooked. Acknowledgments.-Theseobservations were made while the author was supported by funds from the North Dakota Game and Fish Department through Pittman-Robertson Project W-67-R. Additional support was provided by the Biology Department and Institute for Ecological Studies at the University of North Dakota. Helpful editorial comments were provided by R. -

The First Mangrove Swallow Recorded in the United States

The First Mangrove Swallow recorded in the United States INTRODUCTION tem with a one-lane unsurfaced road on top, Paul W. Sykes, Jr. The Space Coast Birding and Wildlife Festival make up the wetland part of the facility (Fig- USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center was held at Titusville, Brevard County, ures 1 and 2). The impoundments comprise a Florida on 13–17 November 2002. During total of 57 hectares (140 acres), are kept Warnell School of Forest Resources the birding competition on the last day of the flooded much of the time, and present an festival, the Canadian Team reported seeing open expanse of shallow water in an other- The University of Georgia several distant swallows at Brevard County’s wise xeric landscape. Patches of emergent South Central Regional Wastewater Treat- freshwater vegetation form mosaics across Athens, Georgia 30602-2152 ment Facility known as Viera Wetlands. open water within each impoundment and in They thought these were either Cliff the shallows along the dikes. A few trees and (email: [email protected]) (Petrochelidon pyrrhonota) or Cave (P. fulva) aquatic shrubs are scattered across these wet- Swallows. lands. Following his participation at the festival, At about 0830 EST on the 18th, Gardler Gardler looked for the swallows on 18 stopped on the southmost dike of Cell 1 Lyn S. Atherton November. The man-made Viera Wetlands (Figure 2) to observe swallows foraging low are well known for waders, waterfowl, rap- over the water and flying into the strong 1100 Pinellas Bayway, I-3 tors, shorebirds, and open-country passer- north-to-northwest wind. -

Effects of Bridge Design on Placement and Shape of Cliff Swallow (Petrochelidon Pyrrhonota) Nests in Southern Arkansas

Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science Volume 67 Article 42 2013 Effects of Bridge Design on Placement and Shape of Cliff wS allow (Petrochelidon pyrrhonota) Nests in Southern Arkansas R. Tumlison Henderson State University, [email protected] K. Kendall Henderson State University Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/jaas Part of the Zoology Commons Recommended Citation Tumlison, R. and Kendall, K. (2013) "Effects of Bridge Design on Placement and Shape of Cliff wS allow (Petrochelidon pyrrhonota) Nests in Southern Arkansas," Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science: Vol. 67 , Article 42. Available at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/jaas/vol67/iss1/42 This article is available for use under the Creative Commons license: Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-ND 4.0). Users are able to read, download, copy, print, distribute, search, link to the full texts of these articles, or use them for any other lawful purpose, without asking prior permission from the publisher or the author. This General Note is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science, Vol. 67 [2013], Art. 42 Effects of Bridge Design on Placement and Shape of Cliff Swallow (Petrochelidon pyrrhonota) Nests in Southern Arkansas R. Tumlison* and K. Kendall Department of Biology, Henderson State University, Arkadelphia, AR 71999 *Correspondence: [email protected] Running title: Bridge Design Affects Shape of Cliff Swallow Nests The Cliff Swallow (Petrochelidon pyrrhonota) is identifiable by its orange rump, pale forehead patch, and square tail. -

Cliff Swallow Petrochelidon Pyrrhonota

Natural Heritage Cliff Swallow & Endangered Species Petrochelidon pyrrhonota Program State Status: None www.mass.gov/nhesp Federal Status: None Massachusetts Division of Fisheries & Wildlife SPECIES DESCRIPTION: The Cliff Swallow is small, pointed-winged, aerial insectivore with a square tail, orange rump, and chestnut-colored throat. They historically nested in large colonies on cliff faces in the western United States, but are now found across much of North America, nesting in the east primarily on artificial surfaces such as bridges, culverts, and buildings. DISTRIBUTION AND ABUNDANCE: Cliff Swallows have been steadily declining as breeders in Massachusetts and are now relegated primarily to small colonies in Berkshire, Franklin, and northern Essex Counties. In the first Massachusetts Breeding Bird Atlas, the mountainous western areas of the state hosted fair numbers of Cliff Swallow colonies, both on natural cliffs Figure 2: Massachusetts Breeding Bird Survey results, 1966-2009. and on human structures such as barns and bridges. The Connecticut River Valley had no shortage of such due to heavy infiltration of House Sparrows. Swallows structures but had only 21% occupancy by blocks, likely were present in similar proportions across the Worcester and Lower Worcester Plateau regions, but Coastal Plains records were almost entirely restricted to the northern parts of the region. Only a handful of Cliff Swallow colonies were reported in the Lowlands and Cape Cod. By Atlas 2, no Cliff Swallows were found in Norfolk, Bristol, Plymouth, Barnstable, or Nantucket Counties. The species entirely vacated the Worcester Plateau as well. The Cliff Swallows that were found in Massachusetts during Atlas 2 covered less than half the breeding footprint of Atlas I and were largely located in the west, where suitable nesting sites (i.e., old barns) could still be found, along with a few sites in northern Essex County. -

TREE SWALLOW Tachycineta Bicolor Tree Swallows Are the Only Swallows to Be Seen All Year in the Sacramento Region

TREE SWALLOW Tachycineta bicolor Tree swallows are the only swallows to be seen all year in the Sacramento region. A few winter here; others come to join them early in the spring. They are about sparrow-length but slimmer. The male is steel blue on top, white underneath. Tree swallows like wooded areas near streams. They can be seen skimming close to the water scooping up insects. Usually a hole in a tree trunk is chosen for a nest and lined with grass, leaves and feathers. The violet green swallow, a bird with similar colors but with white around the sides of the rump, is found here in warm weather. CLIFF SWALLOW Petrochelidon pyrrhonota Cliff swallows, famous for their annual return to San Juan Capistrano, likewise return to the Sacramento region within a few days of the same date each year. Wherever a bridge or culvert houses a colony of these swallows, the same kind of homecoming takes place each spring. Cliff swallows are identified by their buff foreheads, orange rumps, and square tails. They fly with long sweeping glides and steep climbs, catching flying insects on the wing. The bulb-shaped nests, hung under bridges, highway overpasses and eaves of buildings, are built entirely of mud. Flocks of cliff swallows can be seen around puddles gathering mud in their bills. When disturbed by an intruder or when flying over feeding grounds, the birds utter a squeaky, guttural sound. BARN SWALLOW Hirundo rustica Here is a bird with a real “swallow tail” outfit. In fact, it is our only swallow with a deeply forked tail. -

Observations on the Cave Swallow Incursion of November 2005

OBSERVATIONS ON THE CAVE SWALLOW INCURSION OF NOVEMBER 2005 Robert Spahn 716 High Tower Way, Webster, NY 14580 [email protected] David Tetlow 79 Hogan Point Road, Hilton, NY 14468 Since New York State’s first fall record in November 1998 (Schiff and Wollin 1999), the appearance of Cave Swallows (Petrochelidon fulva) during late fall has become somewhat predictable (e.g., Griffith 2005, Mitra 2005, and discussion below). In the context of this emerging pattern of occurrence, November 2005’s incursion to the Lake Ontario Plain was exceptional for several reasons. The first exception was of course the sheer volume of birds encountered, the second was the flight direction of the birds, and the third was the weather pattern, which was only partially similar to what has been linked to these events in the past. The season’s first Cave Swallows were observed in upstate New York on 3 November, when 28 birds were tallied at Hamlin Beach State Park (HBSP) by John Bounds, Judy Gurley, and Dave Tetlow. All of these birds were moving west into a southwest wind ranging from 10 – 20 mph. The high number of birds (highest ever encountered in this region) and the flight direction opposite the norm indicated something was different. On 4 November, with heavy cloud cover and a lake breeze early in the day, no birds appeared. When the weather finally cleared during the afternoon and the wind picked up out of the southwest again, Dave Tetlow returned to HBSP for some late observations. At 3:00 p.m. he observed flocks of five and seven birds pass flying west again. -

The Oriole.Indd 1 5/21/08 9:18:21 AM 2 the ORIOLE Vols

THE ORI O LE Quarterly Journal of the Georgia Ornithological Society Volumes 70 – 71 January – December 2005 – 2006 Numbers 1 – 4 TWO CAVE SWALLOWS AND ONE NORTHERN ROUGH- WINGED SWALLOW ON THE DECEMBER 2002 MACON CHRISTMAS BIRD COUNT Paul Johnson 901 Santa Fe Trail, Macon, GA 31220 Email: [email protected] On 14 December 2002, during the annual Macon Christmas Bird Count (CBC), Walt Bowman, Nancy Gobris, Ty Ivey, Larry Ross, and I observed two Cave Swallows (Petrochelidon fulva) at the Macon Dump in Bibb County, Georgia, between 1500 and 1530 hours. Our team also noted one Northern Rough-winged Swallow (Stelgidopteryx serripennis) at the same location. Around 0800 hours, Ty Ivey, Walt Bowman, and Nancy Gobris found a Northern Rough-winged Swallow at the Macon Water Treatment Site, about 2.5 km (1.5 miles) from the Macon Dump. Because it was possible that our team saw the same individual swallow twice, we reported just one Northern Rough- winged Swallow within our CBC data. We entered the Macon Dump shortly after 1500 hours. The weather was overcast, with a strong westerly wind and cold temperatures. The CBC low temperature on 14 December was 4 C (40 F) and the high was 8 C (46 F). I first noticed a swallow over the lake from our moving vehicle. I saw the light rump and believed it was a Cliff Swallow (Petrochelidon pyrrhonota). As we watched the swallow with our binoculars, we began to consider the possibility of a Cave Swallow. At this point we noticed two other swallows, a second Petrochelidon and a Northern Rough-winged Swallow. -

Kanha Survey Bird ID Guide (Pdf; 11

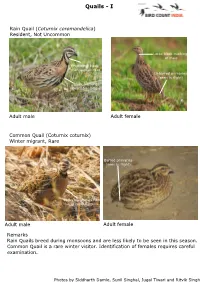

Quails - I Rain Quail (Coturnix coromandelica) Resident, Not Uncommon Lacks black markings of male Prominent black markings on face Unbarred primaries (seen in flight) Black markings (variable) below Adult male Adult female Common Quail (Coturnix coturnix) Winter migrant, Rare Barred primaries (seen in flight) Lacks black markings of male Rain Adult male Adult female Remarks Rain Quails breed during monsoons and are less likely to be seen in this season. Common Quail is a rare winter visitor. Identification of females requires careful examination. Photos by Siddharth Damle, Sunil Singhal, Jugal Tiwari and Ritvik Singh Quails - II Jungle Bush-Quail (Perdicula asiatica) Resident, Common Rufous and white supercilium Rufous & white Brown ear-coverts supercilium and Strongly marked brown ear-coverts above Rock Bush-Quail (Perdicula argoondah) Resident, Not Uncommon Plain head without Lacks brown ear-coverts markings Little or no streaks and spots above Remarks Jungle is typically more common than Rock in Central India. Photos by Nikhil Devasar, Aseem Kumar Kothiala, Siddharth Damle and Savithri Singh Crested (Oriental) Honey Buzzard (Pernis ptilorhynchus) Resident, Common Adult plumages: male (left), female (right) 'Pigeon-headed', weak bill Weak bill Long neck Long, slender Variable streaks and and weak markings below build Adults in flight: dark morph male (left), female (right) Confusable with Less broad, rectangular Crested Hawk-Eagle wings Rectangular wings, Confusable with Crested Serpent not broad Eagle Long neck Juvenile plumages Confusable -

American Swallow Bug, Oeciacus Vicarius Horvath (Hemiptera: Cimicidae), in Hirundo Rustica and Petrochelidon Pyrrhonota Nests in West Central Colorado

Great Basin Naturalist Volume 47 Number 2 Article 24 4-30-1987 American swallow bug, Oeciacus vicarius Horvath (Hemiptera: Cimicidae), in Hirundo rustica and Petrochelidon pyrrhonota nests in west central Colorado Thomas Orr Mesa College, Grand Junction, Colorado Gary McCallister Mesa College, Grand Junction, Colorado Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/gbn Recommended Citation Orr, Thomas and McCallister, Gary (1987) "American swallow bug, Oeciacus vicarius Horvath (Hemiptera: Cimicidae), in Hirundo rustica and Petrochelidon pyrrhonota nests in west central Colorado," Great Basin Naturalist: Vol. 47 : No. 2 , Article 24. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/gbn/vol47/iss2/24 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Western North American Naturalist Publications at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Basin Naturalist by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. AMERICAN SWALLOW BUG, OECIACUS VICARIUS HORVATH (HEMIPTERA: CIMICIDAE), IN HIRUNDO RUSTICA AND PETROCHELIDON PYRRHONOTA NESTS IN WEST CENTRAL COLORADO Thomas Orr' and Gary McCallister' Abstract —Oeciacus vicarius bed hugs were collected i'rom 32% ot'Hirundo ni.stica nests and 83% ofPetroclielidon pyrrhonota nests on bridges in western Colorado in December 1984. A total of 409 bugs (158 adults and 251 juveniles) were counted in 47 nests, two months after the hosts had departed for the winter. Two regular avian visitors to the Colorado lected into 70% ethanol. Mites, ticks, spiders, River system in west central Colorado are the moths, and dermestids were included, but cliff swallow, Petrochelidon pyrrhonota, and the most abundant species was Oeciacus vi- the barn swallow, Hirundo rustica.